Starfighter

Cricket Web: All-Time Legend

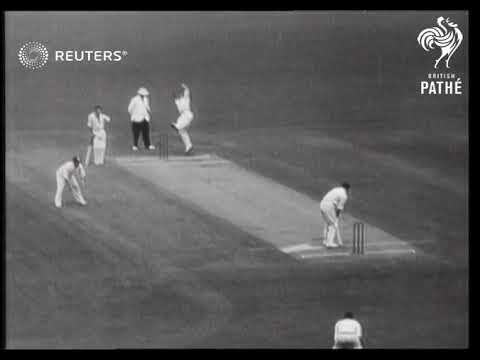

George Pope was lively, high armed Derbyshire fast-medium bowler who played most of his cricket prior to to the war. Although reducing his first class participation and playing more league cricket afterwards, he was still selected for the Lord's test against South Africa in 1947. He made little impression and did not play again. He did the double the next year but promptly retired to look after his ill wife.

Cliff Gladwin was a fast-medium bowler who enjoyed a very long and successful career (also for Derbyshire) who played eight tests in the late forties. Though far from fast he was a tricky, devious bowler who curled the ball in (something very obvious from his action) and who cut it away off the pitch. Harold Rhodes, who played along side him towards the end of his career, estimated his pace as being about seventy miles per hour and even if we give that he was livelier younger we can see that what was considered 'fast-medium' then was considerably slower than today. He was picked for two tests against SA in 1947 and did little, and perhaps this was why he was not picked against Australia the next year despite heading the averages. He toured SA in '48/'49 and was unspectacular in all five tests, with a final test against NZ in 1949 yielding a single wicket.

(and a wicket at 0:41)

(also at 0:52, misattributed by the narrator, and a wicket at 1:29)

Cliff Gladwin was a fast-medium bowler who enjoyed a very long and successful career (also for Derbyshire) who played eight tests in the late forties. Though far from fast he was a tricky, devious bowler who curled the ball in (something very obvious from his action) and who cut it away off the pitch. Harold Rhodes, who played along side him towards the end of his career, estimated his pace as being about seventy miles per hour and even if we give that he was livelier younger we can see that what was considered 'fast-medium' then was considerably slower than today. He was picked for two tests against SA in 1947 and did little, and perhaps this was why he was not picked against Australia the next year despite heading the averages. He toured SA in '48/'49 and was unspectacular in all five tests, with a final test against NZ in 1949 yielding a single wicket.

(and a wicket at 0:41)

(also at 0:52, misattributed by the narrator, and a wicket at 1:29)

Last edited: