Zed

Martin Chandler |

I suppose it must have been half term, but I really can’t recall quite why I was at home with nothing to do on my eleventh birthday. When I got up it had promised to be a good day. I had only just begun to take an interest in Test cricket and was looking forward to watching England take on Pakistan at Edgbaston in the first Test of the summer. I took a great interest in the art of wrist spin back then, so I was a fan of Pakistani cricket. In Mushtaq Mohammad and Intikhab Alam the visitors had two of these strange beasts, both of whom played county cricket.

A day that started full of optimism quickly turned to despair however. Around 11 am, in good time for the 11.30 start, I switched on the television. The set wasn’t ours. It was rented from Radio Rentals, then a famous High Street name in the UK. It was several years before my father bought a set. In those days they were pricey and unreliable, particularly colour sets, which had only just started to become widely available. Not unusually after I switched on the set flickered into life slowly before conking out. I howled with anguish.

It was lunchtime before the man from Radio Rentals arrived. He stayed about twenty minutes. I jabbered away at him explaining all about the match I wanted to see. He put up with it with good humour. I remember to this day his telling me that he came from Karachi and that he had once shaken Hanif Mohammad’s hand. That shut me up.

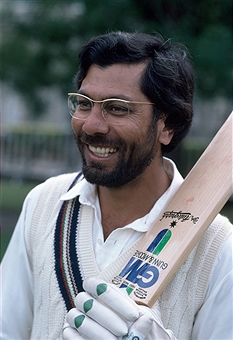

The television duly repaired I settled down to watch the afternoon’s play. I had to do a double take when the batsmen came out because the batsman who walked out to the middle with Mushtaq could easily have been our engineer. The resemblance was uncanny. Even my mother agreed. I had never heard of Zaheer Abbas before, but it couldn’t be my man, as he wouldn’t have had enough time to do the drive.

As Pakistan were batting I was slightly torn to start with. My Lancashire heroes Peter Lever and Ken Shuttleworth were part of an England pace attack that was completed by another favourite, the decidedly rapid Derbyshire man Alan Ward. Sadly for him Shutt went wicketless, and the game proved to be the last of his five caps.

For once though I didn’t mind seeing England being put to the sword. The two Pakistanis batted beautifully and ended the day on 270-1. Zaheer had calmly stroked his way to 159. To me the fact that the wicket was a featherbed meant nothing. My understanding of the minutiae of the game had yet to develop, and all I could see was as stylish a batsman as I had seen in my short life. He went serenely on the next day as well, so much so that at one point I thought he might make a triple century. In the end however he was fourth out at 456 for 274, sweeping at England skipper Ray Illingworth and catching a top edge.

The dismissal was an error of judgment, no more no less. Some batsmen might, after more than nine hours at the crease, have complained of tiredness. Not Zaheer though. He admitted that he was beginning to think in terms of Sobers’ then record 365 and had not felt tired. Throughout his career Zaheer made a habit of going big. He never did get past 274 again, but there were three more Test double centuries and four other innings of more than 150.

No Asian batsman is ever likely to approach Zaheer’s career total of almost 35,000 runs. He averaged more than fifty as well. The only batsman from the sub continent to record a century of centuries in the First Class game he ended up with 108, almost one in three of them exceeded 150. Like Geoffrey Boycott before him he managed his one hundredth in a Test, at home against India in 1982. Perhaps unsurprisingly he converted it into a double. In all First Class cricket Zaheer scored a century in each innings more often than anyone else, eight times. Four of those included a double. It was a feat he never achieved in a Test, although he really should have done. In the first Test against India at Faisalabad in 1978 Zaheer made 176. In good batting conditions the draw was already inevitable and, on 96, another Zaheer century was surely going to follow. Perhaps it was over confidence, but he mishit a drive that he aimed over mid on to give Sunil Gavaskar the only Test wicket he ever took.

Like most successful cricketers Zaheer fell in love with the game as a child. More unusually his family were not cricket people, and had hoped he might qualify as doctor. In deference to his parents’ wishes Zaheer did go to University and graduated in history. He played little cricket whilst at University but, once it became clear that playing cricket was what he wanted to do, his parents supported him. There was a low key First Class debut at 18 in 1966, but little after that until in 1969 the powerful Pakistan International Airlines side invited him to join a tour of Ireland. He was the most successful batsman on the trip, and found himself catapulted into the Test side for the first Test against New Zealand at Karachi. So little known was he at this stage that Wisden manages to misspell his name, which appears as ‘Zahir’ in the 1971 edition. The game was drawn, and with innings of 12 and 27 from number five Zaheer by no means let himself down, but it was not enough to keep him in the side for the rest of the series.

Despite his disappointments Zaheer continued to score heavily in domestic cricket and did enough to gain selection for the 1971 party that toured England. Even then he was not expected to figure in the Test side, but was fortunate to get a place in the match for the traditional tour opener at Worcester when the established Saeed Ahmed pulled out. A century in the first innings pit him in pole position for the Test side and his great innings at Edgbaston. He was comfortably Pakistan’s leading batsman on the tour. In 1972 not only did Wisden spell his name right but he was named as one of the Five Cricketers of the Year. Alex Bannister wrote within weeks he was accepted as a world-class batsman of classical style, with a rich variety of strokes, including a perfect cover drive, and of an imperturbable temperament.

Such was the excitement caused by Zaheer in 1971 that he started to become known as ‘The Asian Bradman’. Few have the same appetite as ‘The Don’ for making tall scores, but there was never any real comparison. Zaheer was a gifted strokemaker and wonderful entertainment when he was on song, but as anyone who followed his career knows he was something of a flat track bully.

In the 1970s there weren’t as many Tests played as there are now. Pakistan did not play agains until 1972/73, and then they played three series and nine Tests in little more than three months. There were three matches in Australia followed by three in New Zealand and then three at home against England. Zaheer was poor. He managed 51 and 25 on a Melbourne wicket that Wisden described as sedated, but otherwise did not pass fifty. In New Zealand he had just 35 runs to show for his five innings. Against England he missed the first Test, and didn’t get past 24 when recalled for the next two.

In the meantime, and hardly surprisingly after his display in 1971, there were plenty of counties interested in securing Zaheer’s services for 1972. It was Gloucestershire who won the race for his signature, but if not quite a flop he certainly didn’t make much of an impact. Qualification rules meant that he had to play for the second eleven until July. He averaged just 31.17 for the seconds. There were as many as six men in front of him in the averages, two of whom were destined to never play a First Class match. It was no better when he did play in the first team as his average there was 26.23, although at least this time there were only four men ahead of him.

The following summer Zaheer upped his average, but only to 30.00, and memories of Edgbaston 1971 must have been a factor in his selection for the Pakistan side that was due to visit in the second half of the 1974 summer. In the early season appearances for which he was available he had a wretched time as his averaged slipped to 15.83. His best score was a lowly 28, and as many as ten Gloucestershire batsmen headed him in the county’s averages.

In the first two Tests against England Zaheer managed 48, 19, 1 and 1 and might have been considered fortunate to retain his place for the Oval. History records that he came good, and scored 240. Wisden records that the pitch was so slow in pace that bowlers were reduced to impotence.

Back home in Pakistan Zaheer achieved little against the West Indian side who played two Tests in Pakistan after their visit to India, but something clicked when he got back to England in 1975. He topped the Gloucestershire averages and went on to become one of the county game’s most consistent batsmen for the rest of his career.

After another international break for Pakistan in October 1976 they entertained New Zealand, not a side with happy memories for Zaheer. As might be expected he did better at home than he had in the Shaky Isles, but only just, scoring just 60 runs in five completed innings. In one of them he contrived to be out lbw to a part time medium pacer – that one must have been absolutely plumb.

At this stage of his career Zaheer took fast bowlers in his stride, but he cannot have been looking forward to facing Dennis Lillee and Jeff Thomson in December 1976. In the event he did pretty well in the three match series, averaged 57.16 and did enough to earn a contract from Kerry Packer’s World Series Cricket. It wasn’t all that it seemed however. Zaheer’s two highest innings were the 85 and 101 he scored in the first Test. He was struggling against Thommo early on and made a hash of an attempted hook and popped up a catch to short mid wicket. Thommo tried to catch it himself and had a sickening collision with Alan Turner that dislocated his shoulder and ended his series. To make matters worse Lillee strained a thigh muscle, and although he soldiered on valiantly he was well below full pace.

A series in the Caribbean followed for Pakistan. The visitors lost 2-1 but should really have won the first Test as well, the last West Indies pair hanging on for more than eight overs at the end. Zaheer did not have a particularly happy tour. He missed the first two Tests because of injury. Fit again he was selected for the remaining three, but other than 80 on a slow wicket at Bourda he achieved little against Clive Lloyd’s pace pack.

It was eighteen months later that Zaheer lined up against India and almost got those twin centuries. From there he recorded an unbeaten 235 in the second Test at Lahore and for the three match series averaged 194. It is said his treatment of them hastened the retirement of the ‘Holy Trinity’. Erapelli Prasanna did not play again after Lahore and Bishen Bedi and Bhagwhat Chandrasekhar called it a day after the tour of England that followed.

Zaheer continued his form into a short series in New Zealand, which no doubt eased the painful memory of his previous visit, but from there he went into another trough having very little to show for home and way series against Australia and a six match encounter in India. Pakistan lost that series 2-0 and Zaheer averaged less than twenty and suffered the indignity of being dropped for the final Test.

A year after the defeat in India, in December 1980 the West Indians visited Pakistan. The pace attack comprised Malcolm Marshall, Sylvester Clarke, Joel Garner and Colin Croft. It was probably not quite the best combination that the West indies fielded during their years of domination, but it must surely rank as the most frightening. Clarke and Croft were terrifying at the best of times, and Garner’s height and bounce did nothing to relieve a batsman’s tension. As for Marshall he wasn’t quite the bowler he later became, but in these early days he was at his fastest, and his skiddiness a potentially lethal alternative to the steepling bounce and menace of the other three.

Zaheer missed the first Test with a shoulder injury. Imran described it as a pretext, but he was back for the next three Tests. He had a torrid time and was a struck a fearsome blow on the helmet by Clarke in the third Test. Imran wrote later that he looked thoroughly suspect against pace and was in a terrible state against Marshall and Clarke, actually backing away from the fast bowling.

Imran went on to express the view that that series against West Indies was the beginning of the end for Zaheer, although that is not quite what happened. A year later Zaheer had his best series in Australia, averaging 56, but increasingly he was effective only on his home pitches where, Dennis Lillee, for one, would complain bitterly about the virtual impossibility of getting an lbw decision against him.

The last prodigious performance of Zaheer’s career came in the six Test home series against India in 1982/83. In the first Test he got that hundredth hundred and went on to 215. He followed that up with 186 in the second Test and 168 in the third. He topped the Pakistan averages in the 3-0 victory with 130.00. It was however a weak Indian side. Only Kapil Dev offered a serious threat with the ball, his fellow bowlers and fielders all letting him down. Mudassar Nazar and Javed Miandad also averaged more than 100 for Pakistan, and Imran and Mohsin Khan each averaged over fifty as well.

By 1983 Zaheer was 36. The one honour in the game that had eluded him was the captaincy of his country. He had hoped to get the job when Javed got it, and when his reign ended had expected to be appointed in front of Imran. There can be no doubt but that the selectors made the right choice, but Zaheer was not happy about a man five years his junior getting the nod. He was quoted as saying he felt insulted and humiliated at not being asked and he described Imran as a young boy. Despite that his performances against India are testament to his professionalism in not allowing his disappointment to adversely affect his performances.

Having doubtless assumed the leadership had passed him by Imran’s shin splints opened up an unexpected vacancy for the three Test series in India in 1983/84 and this time the selectors’ choice was Zaheer. The series was a disappointment. All three Tests were drawn and neither side ever gained the upper hand. Wisden drew a comparison betwenn Imran and his successor and adjudged Zaheer as lacking the same inspiration and initiative.

Later that season Pakistan were due in Australia for a full five Test series. Zaheer was reappointed, until the BCCP President intervened and reinstated Imran. Despite it being clear that he would not be able to bowl, and unclear whether he would be fit enough to take to the field at all, Imran accepted the job. The first thing he did on arrival was to see a Brisbane specialist for a second opinion. He was told not to play at all for two months. On hearing this news the Board instructed him to stay with the team, but appointed Zaheer as captain. As soon as his appointment was confirmed Zaheer made a statement stressing he was only a stand in, and that the team he had at his disposal was not the one that would have been picked had he been involved in the selection process. It sounded like he was getting his excuses in early.

With Imran in the stands Pakistan lost the first Test by an innings and, had the weather not saved them, the second would have gone the same way. They made a much better fist of drawing the third Test but Imran decided he had to return to the side, as a batsman only, for the last two Tests. He did well in the fourth, another draw, but achieved nothing other than aggravating his injury in the ten wicket defeat in the fifth. A big innings eluded Zaheer, who didn’t get past 61, but he battled away and, to his credit, emerged from the series with 323 runs at 40.37.

Less than two months after returning from Australia Pakistan had a third series of the season, this time at home against England. In fact they had never, up until then, beaten England in a home series nor indeed won a Test. With Javed injured as well as Imran Zaheer’s appointment was, for once, clear cut. He got the elusive victory in the first Test, thanks to Abdul Qadir, Sarfraz Nawaz and, some claim, surreptitious doctoring of the wicket by the ground staff. The second Test was a tedious draw and the final Test a rather more interesting draw. Zaheer’s captaincy was once again criticised for lacking any sort of sense of adventure. Given the history of the contest however it seems harsh to complain about his seeking to sit on a lead, and without a brave innings of 82 not out from him in the first innings of the final Test, batting with a runner because of a groin injury, Pakistan might well have surrendered that lead.

When Zaheer arrived back in Gloucestershire for the 1984 season he could justifiably claim to have had a difficult winter. He had played in as many as eleven Tests with the added burden of not only the captaincy but the stresses that came with that given Imran’s colossal presence in the background. He started off as if nothing had happened with an unbeaten 157 against Kent, but in thirteen more matches he did not pass the century mark again and was but a shadow of his former self. Physically and emotionally exhausted he was allowed to return home at the end of July. The county hoped he would return refreshed in 1985, but in the end it was a low key ending for Gloucestershire’s most prolific batsmen when he announced in the spring of 1985 that he had retired from the county game.

Whilst still captain of Pakistan Zaheer wasn’t quite ready to let his international career end as well and he led the side in October 1984 for the home series against India. For the first Test in Faisalabad he asked for and got a side with just three specialist bowlers. The city’s Mayor described the wicket as that barren and wretched piece of earth, but it took Zaheer, who scored an unbeaten 168, to show his batsmen what to do with it. The second Test was another bore draw before, called back because of the assassination of Indira Gandhi, the Indians called off the final Test.

Zaheer retained the captaincy for a home series against a New Zealand side lacking Richard Hadlee. Pakistan won 2-0, but their captain achieved little with the bat. For a return series in New Zealand Zaheer was back in the ranks, Javed having been appointed in his stead. With Hadlee back it was the New Zealanders turn to win 2-0. Zaheer did not arrive until after the first Test, and had a wretched time when he did, scoring just 24 runs in his four innings.

The end came nine months later when Sri Lanka, fresh from their first ever series victory, over India, arrived in Pakistan for a three Test series in October 1985. Zaheer certainly went out with a whimper rather than a bang. He didn’t get to the crease in the first Test and then scored just four in the second, announcing his retirement during the match. According to Wisden he pulled out of the final Test of the series whilst making it clear he was still available for ODIs. Other sources describe him as being denied a farewell Test in the final match of the series. Either way he was not selected to play for Pakistan again.It was a disappointing finale for a man who, if he had never lived up to that tag of being ‘The Asian Bradman’, had still scored more than 5,000 runs at 44.79 in 78 Tests.

After retirement Zaheer did some coaching, and wrote from time to time for an English language newspaper as well as having an interest in a construction business. An intelligent and well read man with an urbane and relaxed personality Zaheer is ideally suited to the ambassadorial role he has recently been appointed to as President of the ICC. He is not quite so adept in more pressurised roles, so let us hope the game does not have any real crises under his presidency. I am reminded of his management of the 2006 Pakistanis and the furore at the Oval when, amidst suggestions of ball tampering by the umpires skipper Inzamam refused to allow his team to resume play after an interval – Zed was conspicuous by his absence once the going got tough.

Leave a comment