Yosser’s Tale

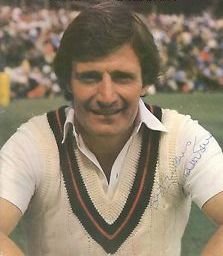

Martin Chandler |

In the early 1970s cricket’s Old Trafford was home to a side almost as glamorous as that which occupied the other Old Trafford, not much more than a good six hit away. After years of mediocrity everything had changed at Lancashire with Jack Bond’s appointment as captain in 1968. Bond managed to blend a good crop of local youngsters with a pair of international greats, Clive Lloyd and Farokh Engineer, and if the County Championship was not quite won Lancashire were the undoubted kings of one day cricket.

I was just eight when Bond took over, and like most of my peers was more interested in the newly established short form of the game than anything else, and the Lancashire cricketers were my heroes. It no doubt helped that none of them were away with England very often. Batsmen David Lloyd, Barry Wood and Frank Hayes, and bowlers Peter Lever and Ken Shuttleworth all played Test cricket, but none ever secured a regular place. My own favourite amongst the locals, David Hughes, was talked about for a berth in the 1972/73 party that visited India and Pakistan, although in the main only within the county’s borders.

Cricket was in Hughes’ blood, his father having been a league professional. He passed the old 11 plus exam, so had the benefit of a grammar school education, but cricket was still his ambition, and he was taken on to the Lancashire staff at 18, and within two years was topping the second eleven bowling averages and had made his First Class debut. That was the summer before Bond was elevated to the captaincy, and he had played a few games with the second eleven, so had had a good look at Hughes. Given that Lancashire at the time had a dearth of spin bowling resources, and that Hughes had the youth and vitality in the field that Bond was after, he became a first team regular straight away once Bond took up the reins.

As an orthodox left arm spinner Hughes was steady rather than spectacular. His run up began behind the umpire, so the batsman saw him for little more than his delivery stride. He was not the slowest on the circuit, but was certainly not an Underwood type of bowler. In List A games he pushed the ball through, and despite having the natural advantage of long strong fingers even in First Class games did not impart a great deal of spin, nor did he give the ball much air. The lack of biting turn meant that he was unable to trouble the best batsmen on good wickets, or always take full advantage of favourable conditions, but with a bevy of athletic fielders to support him he was very difficult to score from in the shorter forms of the game, and that was what his captain wanted.

With the bat the young Hughes was always promising, and in a Lancashire side with a long tail was a useful man to have going in down the order, but in his early years he was a man for the occasional cameo rather than consistent contributions.

What will forever remain Hughes’ greatest moment came in the Gillette Cup semi-final at Old Trafford in late July 1971, a match that has come to be known, with good reason, as the “Lamplight Match”. Lancashire were into their stride by now, and were the holders of the trophy. They were at full strength against a Gloucestershire side made up in the main of honest toilers, the experienced backbone of the English game. But there was also a superstar in their midst. He was not yet 25, but was one of the fastest bowlers in the game and the previous winter had scored six consecutive centuries. No one took liberties with Mike Procter.

Old Trafford played host to an expectant sell out crowd. In those days there were 60 overs a side. Lancashire, as they generally did, chose to bowl first on winning the toss and the visitors, thanks in large part to 65 from Procter, scored 229-6. More than 40 years later that does not seem a big total, but in those days it was a challenging target, albeit one that Lancashire expected to be able to chase down. For Hughes the innings was a huge diappointment. He was easily the worst of the Red Rose attack, going for as many as 68 in the eleven overs he bowled, with just a single wicket to his credit.

Lancashire started their reply well, Wood getting a half century and the score reaching 156-3 before all-rounder John Sullivan fell. Then the 38 year old off-spinner John Mortimore seemed to have turned the game, as he dismissed Clive Lloyd and Engineer to leave the home side reeling on 163-6. To make things worse the light was closing in. An hour’s play had been lost in the early afternoon, and with 120 overs to fit into the day time was always tight. The umpires might have taken the players off at 7.30, but they had been encouraged to allow play to continue in the competition whenever possible. Bond could nonetheless have asked to come off, and the chance to come back next day in good light, but in a display of selflessness that would not happen today, reasoned he had to play on rather than disappoint the huge crowd.

The Gloucester side were not beyond a bit of gamesmanship, and they slowed the game down, and although Bond and Jack Simmons kept the scoreboard moving the sky got darker and darker until Mortimore got rid of Simmons. When Hughes came out to join Bond the equation was 27 needed from six overs with three wickets in hand, and it was getting on towards 9 o’clock. There is a story, in my view almost certainly apocryphal, that on his arrival at the wicket Hughes mentioned the light to umpire Arthur Jepson, whose retort was You can see the moon, how far do you want to see?

Forty miles north of Old Trafford I was glued to the television. The light looked perfect on the screen, but as my Dad explained to me that was thanks to the TV cameras. He turned the living room lights off and drew the curtains back to show me what things looked like to Bond and Hughes. It was very dark indeed. And then I finally, thanks to the commentators, noticed the giveaway on the screen – it may have looked bright enough, but the lights in the pavilion were shining like beacons.

Hughes, 24, looked to his captain for advice. By the time his destiny arrived there were just five overs left, and still 25 runs needed. Bond told him to hit the ball if he could see it, but if at all possible to try and hit straight. Gloucester’s skipper was Tony Brown. He must wish now that he had brought a seamer back, but he stuck with Mortimore, who had after all brought Lancashire to their knees, and was, having won nine caps between 1958 and 1964, his only England player.

Hughes had a slightly unusual, almost closed stance at the wicket, with his front foot nearer to the line of off stump than his back foot. Mortimore’s first delivery eased the tension a little as Hughes took a step down the wicket, opened the blade and struck the ball to the extra cover boundary. He shaped up to the next ball in much the same way, but this one went much straighter, and over the mid on boundary. It might not have been six earlier the day, but the hordes of Manchester schoolboys who ringed the boundary edge had succeeded in pushing the rope in a few feet, but it still went in the book as six.

The pace dropped off for the next two deliveries. The first of them was met by a classical off drive and Bond just managed to scamper back for the second. Next up Hughes for once ignored his captain’s advice and we saw an ugly cross-batted hoick through mid wicket, but the corollary of the batsmen having trouble with sighting the ball was that so did the fielders, and there were two more runs to be had, rather more comfortably this time.

The text book came back out for the penultimate delivery and a cover drive that Walter Hammond would have been pleased with whistled to the cover point boundary. Gloucester had started the over as huge favourites but by its last ball, by then needing just seven runs in more than four overs, Hughes had completely turned the tables. It looked like he had played an ordinary on drive to Mortimore’s last effort, but he must have timed it superbly as despite the lack of any obvious power in the shot it sailed over the long on boundary for six more. That was 24 from the over and Lancashire all but home. Not that the crowd seemed to be totally cognisant of the need for another run as the invasion began, only for Bond and Hughes to wave the masses back. By now it was all but nine o’clock and the BBC were planning to put back their flagship news programme.

Bond cannot have seen much as Procter steamed in as fast as he could for the 57th over, but thanks to Hughes he only had to bide his time, and the fifth delivery of the over was squirted past point to produce the required single. A tsunami of young supporters immediately engulfed the rope, the ball and the Gloucestershire fielders as Bond and Hughes made their dash for the pavilion. Cricket has seen plenty of dramatic overs since 1971, and in fairness to Hughes he had a few moments of his own to come, but none has ever happened in the sort of gathering gloom in which Lancashire triumphed that evening in 1971.

In the First Class game in 1970, and again in 1971, Hughes took 82 wickets and impressed all observers. Given that spinners are expected to improve with age great things were expected from the 24 year old. In the event his bowling never touched the same heights again. His form fell away somewhat in 1972. Had it not done so then he might well have been talked about for the winter’s touring party in more important places than the pubs and clubs of Lancashire. Then in 1973 there was a new skipper at Old Trafford, David Lloyd replacing the now retired Bond. Hughes missed the first half of the season due to injury, and had a horrible time when he did get back in the Championship side. He was more like his old self in the next two seasons but, Lloyd placing an emphasis on seam bowling, his role changed. He was still a lock in the List A side but spinning teams to defeat in the First Class game was not part of Lloyd’s plans.

In 1976 Hughes had a reasonable summer with the ball, but late in the season a rival left arm spinner, Bob Arrowsmith from the local leagues, came into the Lancashire side with such success that he ended the season on top of the county’s bowling averages. Arrowsmith was no great shakes as a batsman, so didn’t threaten Hughes’ List A place, but he was a big spinner of the ball and for the next three seasons, before both player and county decided he was not going to fulfill his early promise, he kept Hughes out of the Championship side for a good deal of the time. Hughes was still a useful late order striker of a ball, but his batting had not really come on, although there was a vivid reminder of his mighty deeds against Gloucestershire in the Gillette Cup final at Lord’s that season.

The big day out in London saw the Red Rose pitted against Northamptonshire and, sadly for all Lancastrians, saw us plunge to defeat. Tight bowling restricted Lancashire, minus Clive Lloyd who had spent the summer making Tony Greig grovel, to 195-7 in their 60 overs. If the game had turned out differently then maybe Mushtaq Mohammad’s Tony Brownesque blunder might be better remembered than it is. With Lancashire 169-7 after 59 overs, and with two pace bowlers who had earlier in the day had conceded runs at less than two an over both having overs in hand, he chose to let Bishen Bedi bowl the last over to Hughes. The damage on this occasion was 4-6-2-2-6-6. It wasn’t enough and Northants won, not quite at a canter but with something to spare.

1980 was a horrible summer for Lancashire cricket fans, 15th in the Championship and 13th in the Sunday League went with early dismissals by Worcestershire from both knock out trophies. For Hughes the threat of Arrowsmith was gone, but just 405 runs and 26 wickets in his First Class season, and nothing to write home about in the List A matches, suggested that at 33 he was on the way out. It was perhaps fortunate for him that Lancashire were so poor that they could not afford to dispense with the services of such an experienced player. But then in 1981 a strange thing happened.

Whilst Ian Botham’s performances against Australia were distracting Lancashire supporters from a season even worse than that in 1980 Hughes suddenly flowered as a batsman. Not having previously scored more than 555 runs in a season he chose 1981 to beak 1,000, most of them scored in times of crisis when most needed. The following year he scored more than 1,300, at an average of nearly 50, and with three centuries and half a dozen fifties he was suddenly a genuine top order batsman. He also chipped in with 31 wickets at 25, his best haul with the ball since 1976, and the 35 year old had been reborn as a cricketer.

In 1983 the first Championship match of the season saw Hughes carry on where he had left off, recording a career best 153 against Glamorgan, but after that he had a nightmare of a summer, struggling in the end to break 500 for the campaign. By now he was only the most occasional of bowlers, managing just a handful of overs. He fared a little better with the bat in 1984, but lacked any sort of consistency, and after more of the same in 1985 he slipped out of the first team at the end of June, and failed on recall for the August Bank Holiday Roses fixture. In 1986 there were just three List A games and legend has it that a letter of resignation was penned, but not sent. The reason for Hughes’ holding back was that, made captain of the second eleven, he found that he thoroughly enjoyed his cricket. He scored runs and took wickets and, to his enormous satisfaction, he galvanised his young charges so well that they took the Second Eleven Championship.

In the meantime the first team were still lurching from crisis to crisis. Nominally Clive Lloyd was skipper, but in that season although a county could register two overseas players they could only play one so, as was often the case, if Lancashire wanted to play their West Indian speedster Patrick Patterson, then their skipper had to stay in the pavilion. Simmons, Graeme Fowler and John Abrahams all led the side at one point or other, but none could work any magic. That said it was still a major surprise when, at the end of the season, the announcement was made that Hughes, who would be all but 40 at the start of the 1987 season, had been appointed first team captain.

As he embarked on the third phase of his career few expected Hughes tenure in charge to last the five years that it eventually did, but such were his captaincy skills that the county were lifted straight out of the doldrums. In Hughes first season Lancashire were runners-up in the Championship, their best performance for years. There was an immediate transformation on Sunday’s too, and that title was lifted in 1989, and the regular visits to Lord’s started again as well. In 1990 Hughes lifted both the 60 over title (by now called the Nat West Trophy) and the 55 over Benson and Hedges Cup.

The captains own contributions were hardly eye-catching. Over the five years he played in 90 First Class matches, but scored less than 1,800 runs all told. Latterly he started to turn his arm over more often, but there were still just 44 wickets. In 103 List A games he was even less productive, those outings producing less than 700 runs. Here he remained an occasional bowler, with just 11 wickets, and in three of the five seasons he had none at all.

As David Edmundson wrote in 1989 In many ways the captaincy of David Hughes reflects a bygone, some would say golden, age. He is perhaps the archetypal amateur captain. A true figure of authority, maybe not worth his place now on his playing ability. But Hughes the captain still prowls the outfield, badgering and cajoling his side to their maximum potential. He remains an outstanding fielder.

This lack of personal contribution in terms of runs and wickets brought some criticism. In 1989 former teammate Frank Hayes was deeply critical in the press, and ended up resigning his membership of the county. Hughes eschewed the right of reply he was offered and let the success in 1990 do his talking for him. But the subject would not go away, and there was a sad end to Hughes’ five year reign when there was a flaming row on the subject between senior seamer Paul Allott and Hughes on the eve of the 1991 Benson and Hedges final. By then the rest of the squad agreed with Allott, albeit they kept out of the argument. In the end player power won the day. Hughes left himself out of the final eleven and Neil Fairbrother led the side. Lancashire lost, and Fairbrother’s shortcomings were all too obvious.

One young player who made his first team debut in Hughes’ first season as skipper was Michael Atherton, who wrote in his autobiography Hughes was a disciplinarian. There was a big age gap between him and the rest of the team and this enabled him to distance himself easily and enforce strict discipline. The younger players, myself included, were visibly wary of him, and any lapse in concentration or focus would result in a severe tongue lashing,but he also recognised that this leadership by force of personality rather than example was exactly what Lancashire needed at the time

One reason for Hughes success was the signing of the then 20 year old Wasim Akram on a six year contract in 1988. The Pakistani star wrote later; It was a tremendously supportive dressing room under the wise captaincy of David Hughes, with the younger players encouraged to chip in with their thoughts, so not quite an old-fashioned autocratic amateur, Wasim adding that Hughes had a lot to do with creating the happy atmosphere I noticed as soon as I joined the club.

Ian Austin played under Hughes in the seconds before also getting his first team debut thanks to him. His view was that Hughes was the best captain I ever played for and I couldn’t have taken my first steps as a professional under a better man. He was always completely straight. He led by example, and you couldn’t fault his man management. He knew which plays would benefit from a kick up the arse and which players needed a friendly arm around the shoulder at times before adding perhaps most importantly, he never held grudges.

To reinforce Austin’s view there is no better source than Phil De Freitas, already an established international cricketer by the time he joined Lancashire in 1989. Hughes had no part to play in De Freitas’ cricketing development, but the England pace bowler’s view of Hughes mirrored that of Austin; he was in a class by himself when it came to man management. He was one of those guys who knew what to say and when to say it, and we all played our hearts out for him. Perhaps most importantly, he never held grudges.

David Hughes was 44 when he finally called it a day at the end of that 1991 season but for those that thought the freeing up of his place would improve on-field performances there was disappointment in 1992. So Hughes came back again for 1993, this time as manager to make with a new coach, David Lloyd, what was talked of a as a dream ticket. It wasn’t, and although the Red Rose returned to Lord’s, ending up as losing finalists in the Benson and Hedges Cup, that was really a case of papering over the cracks. Hughes, who cannot have been given a fair chance to put his ideas into practice, jumped before he was pushed at the end of the season and, following his resignation, the position of cricket manager disappeared and Lloyd took his duties on board as well. Mike Watkinson replaced Neil Fairbrother as skipper and over the next few seasons the Red Rose bloomed again as, a couple of decades earlier, it had under Jack Bond.

Great piece Martin. Interesting not the least with the story involving your dad, and for Bond playing on so as not to disappoint the crowd.

Comment by chasingthedon | 12:00am GMT 28 March 2014

I was at that Lamplight Match and can assure you there were school girls as well as boys pushing on that boundary rope. 🙂

Comment by Red rose bear | 12:00am BST 13 April 2014