When a Welshman took England to India

David Taylor |

When the England team travels to India this autumn, it’s expected that it wll be captained by Andrew Strauss, or, if for some reason he’s not picked, Alastair Cook. It’s safe to assume that the side will not be led by Alex Gidman, or Glen Chapple, or some county captain who’s never played Test cricket himself. Yet no more than forty years ago that’s exactly what happened with an England Test team that set off for a tour of India and Pakistan.

The Glamorgan captain Tony Lewis, Swansea-born and 34 years old, was the selectors’ choice to lead a team for which he’d never played. Furthermore his vice-captain was to be Mike Denness, whose one Test had come more than three years earlier, against New Zealand. How did this extraordinary situation come about? Lewis had been on the radar for a little while. He’d led Glamorgan to an unlikely Championship in 1969; he’d been on the MCC tour to Ceylon (as it then was) and the Far East in 1969-70; and he’d captained the MCC against the Pakistan tourists of 1971. Yet these were slim credentials to be sure. The team selected, which was announced just after the final Ashes Test of 1972, was missing a few leading players: Geoff Boycott, John Edrich, John Snow and of course the incumbent captain Ray Illingworth. The Leicestershire skipper had an ankle injury which ruled him out of the last few matches of the season – England were led in the one-day series by his former team-mate Brian Close – and clearly wanted to rest it. Even if he’d been fully fit by the date of departure he may not have relished a four-month slog around the sub-continent – the team were to leave in late November and return at the end of March. Illingworth would return for one more season at the helm but missing this trip – and the absence of a senior tour in 1969-70 and 1971-72 – meant that in his four-year tenure he only once – but memorably – led England abroad.

The remainder of the party showed a number of changes from the rather middle-aged outfit that had appeared during the Ashes. It was always unlikely that there would be places for Peter Parfitt, MJK Smith, John Price or, sadly, Basil D’Oliveira, who would have been a popular tourist but must have accepted that at 41 (at least) his England career was over. Tony Greig, the tall, dynamic all-rounder who’d made his debut in the series just finished, was an obvious inclusion – and thus became one of the first South Africans to play cricket in Asia. Only two opening batsman were selected – Dennis Amiss and Barry Wood, a decision that would have an adverse impact during the tour. Wood had made 90 on debut against Australia, while Amiss, like middle-order batsman Keith Fletcher, had been in and out of the side since the 1960s. He had only recently started opening for Warwickshire, and the absence of Boycott and Edrich (both, incidentally, county captains, which would surely have put them in consideration for the tour captaincy) gave him a real opportunity to establish himself. The other specialist batsman was the uncapped Graham Roope, of Surrey. The wicket-keepers were Alan Knott and Roger Tolchard (Bob Taylor was originally picked, but pulled out with a throat infection). Tolchard’s county average of 35 – excellent for a keeper at that time – suggested that he would be able to fill a batting spot if needed. It wasn’t necessary on this trip but that’s exactly what would happen four years later. As for Lewis himself, it seemed unlikely that he would score a mountain of runs. He’d made just over 500 runs in the season, at around 33 – he missed a few games but he certainly had no real case for being selected for his batting alone.

There was a bit more experience in the bowling. Derek Underwood and Geoff Arnold were proven performers at Test level, while Pat Pocock and Norman Gifford would surely have had many more opportunities had it not been for the choice of off-spinner Illingworth as captain. Gifford, though, had played the first three Tests against Australia and then been replaced by Underwood, so he was perhaps a little fortunate to be chosen. The fourth spinner was Jack Birkenshaw, an off-spinner who had preceded Illingworth by leaving Yorkshire for Leicestershire. The bowling was rounded out by two young quicks: Chris Old, another yet to play an official Test (he’d appeared twice against the Rest of the World side in 1970) and Bob Cottam, whose only previous Tests had come on the hastily-arranged trip to Pakistan in 1968-69 – since when he’d moved from Hampshire to Northants.

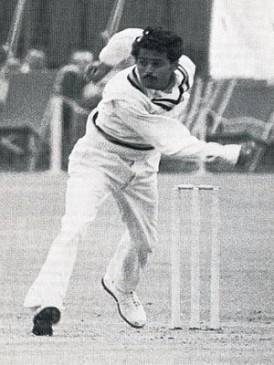

By picking four spin bowlers (Greig was generally only bowling in his quicker style at that time) and only three fast men England were clearly expecting turning tracks, and with good reason. India boasted a four man spin attack which was to become the stuff of legend. Bishan Bedi, with languid left arm spin and Bhagwat Chandrasekhar, with fizzing leg-breaks, top-spinners and googlies were perfectly complimented by a choice of two off-spinners: the tall Srinivas Venkataraghavan (almost universally known as ‘Venkat’) and the shorter and somewhat rotund Erapalli Prasanna. Eknath Solkar at short leg would be expected to snap up anything that came off bat and pad. Their two world-class batsmen, Sunil Gavaskar and Gundappa Viswanath, had the main repsonsibility for ensuring that the spin-based attack had enough runs to defend.

Pakistan were also expected to rely mainly on spin for their wickets. They had some good fast-medium bowlers – notably Sarfraz Nawaz, Salim Altaf and Asif Masood – but they were more effective away from home and it was not unusual for Asif Iqbal or Majid Khan – batsmen who bowled medium pace – to take the new ball. Mushtaq Mohammad and Intikhab Alam were leg-spinning all-rounders who gave the side plenty of balance, while Sadiq Mohammad – the youngest of the famous brotherhood – and Wasim Raja could also chip in with a few overs. Pervez Sajjad was a left-arm spinner to provide some variation, while one batsman who needed no introduction was Zaheer Abbas, who’d announced himself to the world with a colossal innings of 274 at Edgbaston on Pakistan’s last visit to England.

After three drawn warm-up games – which featured hundreds from Wood and Fletcher and eight wickets for Cottam in the final match, against North Zone, England went into the first Test at New Delhi reasonably well-prepared. Arnold proved a slightly unexpected destroyer – the Surrey opening bowler single-handedly reduced India to 43-4 on the first morning – and despite England having a few wobbles with the bat themselves – Lewis collecting a four-ball duck – Greig marshalled the tail to gain a lead of 27. In the second innings India fared a little better, but still needed fifties from Solkar and Farokh Engineer to take the lead beyond 200, Underwood finishing with four wickets. A target of 208 could have been tricky, and Fletcher failed for the second time in the match, but Lewis and Greig added an unbroken 101 to see the visitors home.

In the next Test at Calcutta (and I hope no-one will mind me using the names of places as they were then known) India turned the tables. It was another low-scoring match, in which India’s first innings of 210 was comfortably the highest total, and the toss proved vital with England obliged to bat last. Set 191, they appeared to be out of the match at 17-4, but Denness and Greig then added 97 and Old, making his debut in place of the sick Arnold, followed up an unbeaten 33 with another gutsy knock to see his side lose by only 27 runs. With six wickets in the match Old had done enough to keep his place when Arnold returned, Cottam being the man to miss out. Chandra picked up nine wickets and Bedi seven; these two really were at their peak around this time, and would finish the series with 35 and 25 wickets respectively.

A match against South Zone followed, and former Indian skipper ‘Tiger’ Pataudi, now shown on scorecards as ‘MA Khan’ made a hundred and gained selection for the third Test. Moved up to number three, Knott hit 156 against an attack featuring Venkat and Chandra, while Fletcher’s 100 indicated a return to form. Knott batted at first wicket down for the rest of the series although this was only a qualified success, and was not continued in Pakistan.

With Pataudi recalled and Arnold restored to their sides, the third Test was played at Madras in January 1973. With Knott now at number three the captain dropped himself down to number seven, not an inspiring move from a specialist bat I’d have thought, and I don’t remember it being done again until Mike Brearley did something similar in 1978. It did Lewis little good as he managed only 4 and 11 while India took a 2-1 lead. Fletcher was left stranded on 97 as Chandra wrapped up the tail to finish with six wickets; Pataudi top-scored for India with 73 as they took a decisive 73-run lead – the first time in the series that either side had passed 300. It was hard work for England’s bowlers, who toiled for 135 overs; Gifford, in for Underwood, got through 34 and Pocock 46. England were then skittled for 159 by Bedi, taking the new ball, and Prasanna with four wickets apiece. India had a few alarms, Pocock taking eight wickets in the match – his best return of a quixotic career – but 86 was never going to be enough and the veteran Durani took them most of the way with 38.

At this point Wood and Amiss had played in every Test, but neither had reached 50. Roope opened with Tolchard against East Zone and hit 125, which got him into the next Test at Kanpur (the unlucky Cottam’s 5-25 was unable to do the same for him). With both openers dropped, Roope made his debut going in first with Denness in a drawn game. Both captains top-scored: Wadekar, hitherto rather short of runs, with 90 and Lewis with 125 before being bowled by Abid Ali, one of only three wickets in the series for India’s opening bowler. After another Roope hundred against West Zone (Amiss’s 63 wasn’t enough to win him a recall), the last Test at Bombay was another high-scoring draw. Engineer and Viswanath, another who left it late to make an impression made hundreds, and England had to be rescued from a perilous 79-4 by Fletcher and Greig, whose 148 was his first three-figure score for England. He was the one indisputable gain from the series for the tourists.

After a short trip to Sri Lanka, who lost by seven wickets after being bowled out for 86 on the first day, the party went on to Pakistan. For the first of three Tests, at Lahore, Amiss was restored to the side and went in first with Denness – so England had their fourth different opening partnership in as many Tests. Knott was back in his accustomed position at number seven. After weeks of playing almost nothing but spin England suddenly had to contend with pace bowling again, and although neither Altaf or Sarfraz took many wickets they at least bowled their share of the overs. Denness hit two fifties and Amiss 112, a breakthrough innings which heralded the start of a wonderful 18 months for him. But with Pakistan making 422 through hundreds by Sadiq and Asif, the pitch, as so often in Pakistan, was the winner.

From a result viewpoint the second Test at Hyderabad was even worse – not even three innings were completed. Amiss improved his best score to 158, and Mushtaq and Intikhab responded with big hundreds of their own. Pocock took one of Test cricket’s more expensive five-fors, wheeling away for 52 overs to finish with 5-169. And finally the weary tourists turned up at Karachi for the match of the 99s – Majid, Mushtaq and Amiss all out on that score. Lewis signed off with 88 and Sadiq with 89, so we had totals of 386 and 445 in which no-one reached three figures.

Tony Lewis played one more Test for England against New Zealand the following season, scoring two in each innings. But his day in the sun had come in the autumn of his career – a year later he announced his retirement from first-class cricket, going on to be a BBC commentator and the writer of several well-received books. His appointment was something of a throwback and must have reminded older supporters of Nigel Howard, the Lancashire captain whose only Test cricket was played on the 1951-52 tour of India, leading what was in reality no more than an A side. Lewis was a much better player than Howard but never again would the selectors appoint a captain who had not proved himself in the tough environment of Test cricket.

Leave a comment