West Indies Forgotten Fast Man

Martin Chandler |

Something over which we have no control is the time and place that we are given our opportunities in life. For some people fate plays a perfect hand, whilst for others their talents are never given a proper chance and for a few, like Keith Boyce, there is a halfway house. Boyce had his chance at the highest level, and took it, yet for some reason his name is rarely spoken today despite his being a cricketer who at his peak, and deservedly, drew favourable comparisons with the Caribbean legend Learie Constantine.

Boyce was born in 1943, a product of that small Caribbean island nation that has produced such a disproportionately large number of top class cricketers, Barbados. As a youngster he played for Lancashire, although that was a small village on the island rather than the county of the Red Rose. Later he moved to the famous Empire club in Bridgetown, the nursery of so many of the island’s greats. In those days Boyce was a dour and defensive batsman who bowled leg spin, a very different cricketer to the one who was destined to make his living from the game.

His early pursuit of playing styles that did not suit him held Boyce back, but his breakthrough came in somewhat fortuitous circumstances in February 1965, nine months after a rather sobering introduction to international sport. Towards the end of May of 1964, after a long hard First Division campaign, Chelsea and Wolves took a trip to the Caribbean for a series of five matches at various venues across the region. Including matches against local opposition Chelsea played 11 games in 17 days beginning with a fixture against Barbados, with Boyce in goal. He picked the ball out of the net seven times, and that was the end of any ambitions in that direction.

The game of cricket in February was to be played between Barbados and an International Cavaliers XI. The Cavaliers were made up of a mix of youth and experience but a strong side that contained nine men who either had or would play Test cricket. One of them was Essex and England stalwart Trevor Bailey. The team were managed by former Kent and England wicketkeeper Les Ames. Barbados provided the backbone of the West Indies side in those days, men like Seymour Nurse, Conrad Hunte, Garry Sobers, Wesley Hall and Charlie Griffiths.

There were two First Class games for Barbados against the tourists. The first was drawn by what amounted to a first XI, but on the eve of the second game the Test players were called early to Jamaica where the first Test against Australia was due to begin in a few days. So the side that eventually lined up contained nine debutants, five of whom never played First Class cricket again. They nearly won though, and two of their number, Boyce and John Shepherd, impressed so much on debut that Bailey and Ames had them signed up for their respective counties before the game ended. Still a leg spinner who only bent his back in the nets Boyce was fortunate that Hall and Griffith were both called to Jamaica because, his captain lacking any pace options, he was told he would be taking the new ball. He had only ever bowled quickly in the nets, so it was a challenge, but he impressed Bailey.

When Boyce arrived in England the ability of the counties to sign overseas players on immediate registrations was still three years away, so he spent his first two summers whiling away his time in second eleven and club cricket, where his enthusiasm made a tremendous impact. I have read that in one minor match he enlivened proceedings to the extent of scoring 125 before lunch, and that after not coming to the wicket until 12.30!

So what type of cricketer was Boyce? His county colleague Keith Fletcher described him as a wonderfully athletic crowd-pleaser who would have become a superstar had he been English, and in relation to the limited overs cricket that was coming into the English game wrote that he could have been patented for this form of the game. That view was echoed from a Caribbean perspective by fellow West Indian Deryck Murray when he wrote of how Boyce thrilled spectators throughout the world with his spectacular unorthodoxy.

Fine batsman and bowler that he was my abiding memory of Boyce was of his fielding. In his time he was unique, and few have matched him since. Many was the time a batsman stood admiring his stroke to the boundary when Boyce suddenly appeared as if from nowhere. He would pounce on the ball and pick it up in one swift movement, at the same time as contorting his body in an unnatural looking twisting motion which produced the most remarkable throw I have ever seen. Never was the oft-quoted comparison with a tracer bullet more apt. The ball remained at chest height throughout its momentary journey to the stumps, and all an unlucky batsmen would see would be “Tonker” Taylor whipping the bails off – the more fortunate amongst the batting fraternity just occasionally would be the beneficiary of a throw that was slightly awry, in which case four overthrows may well follow. It was a sad day for cricket watchers when Essex discovered that Boyce was also their best catcher close to the wicket.

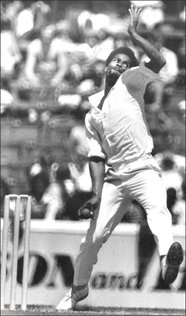

As a bowler Boyce was, in his early days, genuinely quick. As the county circuit took its toll, and he learnt more about English conditions and swing and seam movement, he slowed down to fast medium, but he retained the ability to bowl in a different gear. Like his contemporary Vanburn Holder his pace was rather different when he bowled for West Indies rather than his county.

Most who have written about Boyce have quoted a remark he made about his batting early in his Essex career; I prefer an attacking game, I feel it is my natural instinct to hit a ball. I try to hit it as far as I can, and when it goes a long way I have a deep inner satisfaction. As with his fielding there is a permanent image of Boyce the batsman ingrained in my memory. It is of him going down on one knee and swinging his bat through a full and violent arc. Often the ball would go to the boundary, anywhere between point and square leg, in which case the crowd would purr with delight. Sometimes of course a stump went cartwheeling instead, and the entertainment ended. Some folk are never satisfied, and the same crowd would then shake their heads and criticise Boyce’s shot selection.

In 1966 Boyce was able to make his First Class debut, in a match against what would have to be accepted was a modest Cambridge University side, albeit one skippered by his future West Indies teammate Murray. In a match of remarkable contrasts his first innings did not trouble the scorers, so he could only ever get better with the willow. With the ball he took 9-61 as only Murray, last man standing, was able to deal with him. As Wisden observed he was simply too quick for the students. He blew away their top order in the second innings as well, including Murray this time, and only Bailey’s decision to give his spinners some match practice prevented him getting more wickets – Boyce went through his entire career never improving on those debut figures.

Qualified at last in 1967 the always enthusiastic Boyce played in all of Essex’s 28 Championship fixtures. His returns with bat and ball were relatively modest but, amidst a plague of no balls and too many impetuous shots, his fielding made him a firm favourite from the off. A winter tour to Pakistan with a Commonwealth XI under the wing of Richie Benaud helped his bowling technique enormously and although overstepping was still a problem his impact was rather greater in 1968. Two matches in particular, against Middlesex when he took 10-48, and then against eventual champions Yorkshire when it was 11-125, resulted in victories that would almost certainly not have happened without his contributions.

Back in Barbados in 1968/69 Boyce scored his first century, a relatively slow (by his standards) three hour effort that dug his side out of a bit of a hole against Guyana. He followed that up with two more in the following English summer, including what was to remain his highest ever score, an unbeaten 147 against Hampshire which led Essex to a victory that had looked deeply improbable when he arrived at the crease. This was also the first summer of England’s first 40 over competition, John Player’s Sunday League. Boyce was third in the national bowling averages, the only quick man to enjoy sustained success, and he also scored the fastest fifty in the competition against eventual winners Lancashire. He won the single wicket competition as well, an annual event in the late 1960s at which sponsors threw a good deal of money. The tournament never really caught on with the public, but it was made for Boyce who, after defeating the mighty Sobers in the first round, scored a rampant 84 from 46 deliveries in the final – and that after being pole-axed early in the innings when his head got between the wicketkeeper and a full-blooded return from the field as he attempted to steal a quick run.

By 1970/71 Boyce had finally done enough to catch the eye of the West Indies selectors and he was included in the side to play India in the third Test of that series. The Indians caused a major upset by winning an away series for the first time. Considering how strong it would be half a decade later the West Indians pace attack was very weak at this point, and after taking a couple of inexpensive wickets and bowling economically Boyce must have expected to be retained for the fourth Test on his home island. In the event however the selectors chose to replace all of the bowlers, and a disappointed Boyce was not selected again against the Indians, nor against New Zealand the following year, another disappointing series for West Indies in which a consistently effective pace attack was again conspicuous by its absence. Boyce had not enjoyed a particulary good summer in 1971, the highlight being a record haul of 8-26 against Lancashire on a Sunday afternoon, but he still felt he was being ignored by the selectors, and was becoming disenchanted with Test cricket.

Perhaps by reason of the perceived snub Boyce produced his best summer’s work yet in 1972, coming close to doing the double. He averaged more than 30 with the bat and less than 20 with ball. During the season he confided in Bailey that he did not intend to return to the Caribbean that winter to fight for his Test place. Bailey was caused sufficient disquiet by this to share his concerns with the President of the Barbados Cricket Association who then sought Boyce out, promised him off-field employment that winter as a car salesman, and with that was able to persuade Boyce to make the trip after all.

Australia were touring the Caribbean in early 1973 and although Boyce was not picked for the first Test he played in the other four matches in the series. At first blush his return of just nine wickets at 37.77 runs apiece would suggest that he was fortunate to play through the four games, two of which were lost. There is however a simple explanation, as there were simply no alternatives. Holder was the second most successful West Indian quick in the series, but his four wickets cost almost 70 runs each. With the bat Boyce got into double figures in each of his six innings, but only twice past 12 with a high score of 31, so if he failed to deliver there were at least grounds to hope for better things to come. Looking at the shape of the West Indies attack just three years on it seems barely believable that in the final Test of that series Boyce’s opening partner was Clive Lloyd, and the attack completed by three specialist spinners, none of whom had any pretensions as batsmen.

Unremarkable though those figures against Australia might appear at first glance Boyce was included in the party led by Rohan Kanhai that was scheduled to play three Tests against England in the second half of the 1973 season. Despite their world beaters, Sobers especially, it had been a difficult few years for West Indies and it had been 20 Tests stretching back over seven years since they had last won a match. Boyce had a few games for Essex before joining the party, and his confidence must have been high after he did enough to end the season at the head of both their batting and bowling averages. After that there was something of a slump in Boyce’s form in the early tour matches, although his place in the starting line up for the first Test was never in doubt and, as the tourists finally brought their dismal run to an end, he was undoubtedly their matchwinner.

West Indies batted first and on the second morning Boyce, batting at number nine, came in at the fall of the seventh wicket when the score was 309. He went on to score a fine 72 as the last three wickets added 106. This was a mature Boyce and not the somewhat injudicious hitter that he often was for Essex. There were some big hits, most notably a huge straight six into the pavilion seats from the bowling of Tony Greig, but he also marshalled Inshan Ali and Lance Gibbs very well. In England’s reply he took 5-70, in tandem with Sobers blowing away the lower order as the last five England wickets went down for ten runs to give the tourists a lead of 158. England’s fourth innings target was 414, and they fell well short, Boyce’s 6-77 again contained a clinical exhibition of how to deal with the tail.

The second Test was a forgettable affair, West Indies setting out to draw the match from the first delivery and, not without some controversy along the way, they achieved that comfortably. Perhaps still feeling the affects of his efforts at the Oval Boyce contributed very little. At Lord’s in the final Test a return to form for Boyce resulted in another win. He scored a breezy 36 at the end of West Indies’ mammoth first innings 652-8 declared, and he then took four wickets in each innings in a crushing innings victory.

Understandably Boyce received the “Man of the Series” award, and his efforts resulted in his being one of Wisden’s Five Cricketers of the Year in its 1974 edition.

Six months later a return series took place in the Caribbean when, thanks to some fine “backs to the wall” defending in the early Tests, and Tony Greig’s finest hour with the ball in the fifth Test, England drew the series. It was to be 16 years before they took a Test from West Indies again. This time round Bernard Julien was the West Indies’ main man, but he received valuable support from Boyce, who missed one Test with a heel injury. Persistent niggles meant he only played in twelve of Essex’s Championship fixtures in 1974, and his form suffered as a result.

The end of Boyce’s international career was now approaching, and he had a wretched time on the sub-continent in 1974/75 as a young Andy Roberts’ successes heralded the entrance of a new and ruthless generation of West Indian fast bowlers. There was however still time for Boyce to help West Indies to the first World Cup. The final is rightly remembered for Clive Lloyd’s superb century, but without Boyce’s 34, and his 4-50 in the Australian innings, the result would have been very different. He enjoyed a good season for Essex as well, and indelibly stamped himself on one match in particular, against eventual champions Leicestershire. First of all he struck his fourth and last First Class century, in 58 minutes, the quickest in the Championship for 38 years, and he then took six wickets in each innings as the eventual champions just clung on for a draw after following on.

Australia had arranged a home series against South Africa for the Southern Hemisphere summer of 1975/76. When that was cancelled the West Indians, with nothing else planned, were approached to replace them. They willingly accepted and what was seen as a contest between the two leading sides in the world unfolded over six Test matches. There was plenty of good cricket played, not just by the Australians, but the result was a thumping 5-1 victory for the hosts and there was no real contest. In the battle of the quick men Dennis Lillee, Jeff Thomson, Gary Gilmour and Max Walker were much more effective than Roberts, Boyce, Julien, Holder and a young man called Michael Holding. The difference in quality between the two sets of bowlers was not however that great – the issue was the batsmen’s self-discipline – Frank Tyson summed it up in three words when he titled his account of the tour The Hapless Hookers

Boyce played his last four Tests in that series, and paid more than 40 runs each for his nine wickets. Wisden’s report on the tour stated that the reasons for the poor performance were impossible to explain except to say that perhaps he was guilty of not working hard enough at his game. The almanack is seldom wrong, but I hope that future students of the game will not treat that as the last words on the cause of Boyce’s woes. His keenness to play and practice throughout his career is well documented, and Tyson explains that he had a niggling back injury that reduced him to nothing more than an average county medium pacer after the fourth Test. It is also worth noting that amongst the disarray of some of his teammates Boyce headed the visitors batting averages in the Tests, and although the innings failed to save the game former skipper Kanhai was moved to describe himself as most privileged to witness his knocks of 95 not out and 69 in the fifth Test, bad back and all.

The back strain had resolved itself in time for the start of the 1976 English season, but unfortunately it was replaced by a knee problem that affected whether Boyce could play at all, and when he could his bowling was much less effective than usual. The following season the knee was no better, and after six games it forced him into retirement. He was 33.

Arthritis set into his knee and Boyce never walked without a limp again. His had been a career with plenty of highs, but the cricket world quickly forgot the man who, in 1973 at the Oval, had led the West Indies out of the doldrums and on the road towards the dominance that they were to enjoy for a decade and a half. Back in Essex he enjoyed a decent benefit but, amidst a marriage breakdown, the proceeds of that ebbed away and his alcohol consumption, never low, went up and up. Eventually, after his home became victim to a hurricane, he was handed back some of his dignity with a job that combined helping to run the Barbados Cricket Association lottery and coaching youngsters. But with damage already done and an inability to give up alcohol completely on 11 October 1996, his 53rd birthday, Keith Boyce succumbed to a heart attack. They do say that only the good die young, and all who knew him said Stingray was one of the very best, as a man as well as a cricketer.

Wonderful. A bit before my time, but still a known Essex legend. Just the sort of profile I like to read. Good stuff.

Comment by HeathDavisSpeed | 12:00am BST 12 September 2014

I thought this was going to be about Wayne Daniel, who would be up there with the greats if Clive Lloyd hadn’t had a personal grudge against him.

In 1973 the West Indies fast bowling armoury of Boyce, Holder, Julien and Sobers was considered quite potent. I did like Keith Boyce as a cricketer. It wasn’t until he passed away that I became aware of his health problems. The only interview I ever saw with him was during the tea break of a John Player League match in 1977. He was a very sensitive man. When interviewer Peter Walker gave him a cheque for funds raised as part of his benefit year he was so choked up he couldn’t speak.

Comment by Lillian Thomson | 12:00am BST 14 September 2014

What a brilliant article about a cricketer, that I apparently and sadly knew far too little about.

Comment by kyear2 | 12:00am BST 14 September 2014

My Dad was a keen county cricket watcher through the 60’s and 70’s and used to wax lyrical about the fielding exploits of the West Indians on the circuit, especially Sobers, Lloyd and Boyce.

Comment by Flametree | 12:00am BST 16 September 2014