Vinoo

Martin Chandler |

There are a whole generation of cricketers who lost their best years to the Second World War. In England the point is usually made with reference to Len Hutton and Denis Compton, but there are plenty of others. Australians rue the effect of the conflict on the career of Keith Miller and their neighbours from across the Tasman that of Martin Donnelly.

In India the man who suffered most was Mulvantrai Himmatlal Mankad, universally known, then as now, by his nickname Vinoo. After making his Test debut at the relatively advanced age of 29 in 1946 Vinoo went on to establish himself as an outstanding all-round cricketer. He was not the only talented cricketer the Indians could call on in the immediate post war years, but he was often left to stand alone in difficult conditions.

Vinoo was born in Jamnagar, the land of Ranji and Duleep, so cricket was ingrained in the local culture even if there was no history of the game in Vinoo’s family. He was fortunate to come under the watchful eye of one of the succession of Sussex players recruited by the state as professionals, in his case Bert Wensley. With Wensley to mentor him with the ball and the magician Duleep with the bat Vinoo could hardly fail.

It is with the ball where Vinoo’s quality is perhaps overlooked. He bowled orthodox left arm spin and in his 44 Tests ended up with 162 wickets at 32.32. His great successor, Bishan Bedi played 67 times, and took 266 wickets at 28.71. They have all but identical economy rates. Those numbers suggest that Bedi was a better bowler but they ignore one important difference. Vinoo played his international cricket with a group of men who were, by and large, poor fielders and even the best of them were little better than adequate. In Bedi’s time too it was not unknown for some Indians to be unreliable fielders, but he also had the security of knowing that in Syed Abid Ali, Ajit Wadekar and Srinivas Venkataraghavan he had three high quality close catchers, not to mention Ekki Solkar, to this day in the opinion of many of us of a certain age, still the greatest of them all. It does not seem unreasonable to conclude that with the same support in the field Vinoo’s record would have matched Bedi’s and possibly even surpassed it.

Something that Vinoo and Bedi had in common was pace, or rather lack of it, both men being genuinely slow bowlers. Vinoo’s approach to the wicket was three leisurely steps before beginning his short three pace run. Where the two differed was that Bedi had a classical high arm that all but brushed his ear as he bowled. Vinoo was almost round arm by comparison. Their routes to the wicket were different as well, Bedi’s being at an acute angle as he ran between the umpire and the stumps. In contrast Vinoo’s run up was straight, and his anticipation and athleticism such that he was a magnificent fielder to his own bowling. If he had a mid on or mid off in his field they could always afford to be wider than normal.

There was plenty of variety to Vinoo’s bowling. His stock delivery was the standard leg break. He did not turn the ball a lot but, as the saying goes, turned it enough and did so sharply. He also had an arm ball and a quicker delivery. Indian writer Sujit Mukherjee described the latter as scuttling from the pitch like a worried rabbit, and the former as unannounced as the breeze which springs up at midnight. Despite his batting responsibility Vinoo was also a man for marathon bowling stints, Mukherjee likening his left arm to an inexhaustible storage battery. Another similarity between Bedi and Vinoo was that they gave the batsmen no respite. Once either was ‘in the groove’ a maiden over would take little more than a minute to complete.

As a batsman Vinoo was nothing if not versatile. He was an excellent team man, always happy to move up and down the batting order to suit his side’s needs. In 1946, for example, he had five innings in the three Tests against England. In two of them he opened the batting, in two more came in at number eight and his position was four in the other. In years to come he was most frequently an opener, particularly when the going was tough such as in Australia in 1947/48 and England in 1952, but on one occasion, at home against England in 1951/52 he came in at ten and nine, so almost emulated the great Wilfred Rhodes in batting in all eleven positions in the order.

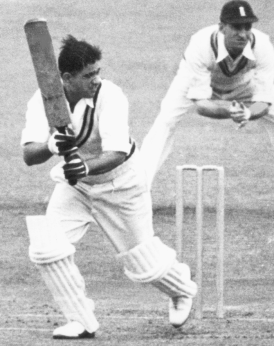

Given that he spent much of his time at the top of the order it is unsurprising that Vinoo’s batting was built on a sound technique, but he was more than capable of scoring quickly. He was a particularly powerful driver and was also strong on the leg side. One contemporary Indian writer described him as an improvisatory and flamboyant genius – perhaps not so much in Tests, but in the middle of his career when he was a much in demand and hugely successful league professional in England he was certainly a crowd pleaser.

In his early days Vinoo was primarily a batsman. He couldn’t initially decide whether to bowl his orthodox slow left arm, wrist spin or medium pace and it was as a batsman that he earned his First Class debut against an Australian touring side as an 18 year old in November 1935. The tourists were led by Jack Ryder by then a veteran, as were many of his teammates including the great Charlie Macartney, but there were five Test players in the side that beat Western India so it was no disgrace that Vinoo was dismissed for 8 and 4, beaten both times by Ron Oxenham. He was no more successful against the tourists a few days later playing for Jamnagar, scoring just a single this time before Oxenham did him again. But he was given a long bowl this time, and at least had the wickets of Wendell Bill and Lisle Nagel to show for his efforts, hitting both men’s stumps.

Had Vinoo had a bit more luck it is possible that he might have earned a place in the party that toured England in 1936, but that trip came a year too early for him, and the fact that India then played no further Test cricket for ten years is the reason for the belated start to his Test career. Would he have done well had, for example, the proposed 1939/40 England trip to the sub-continent gone ahead? It seems certain that he would have done and we know that from his performances against a strong English side skippered by former England captain Lionel Tennyson that toured in 1937/38.

Tennyson led a group of fifteen all bar two of whom had or would go on to play Test cricket. Unlike Ryder’s Australians these were in the main young men looking to build a career rather than veterans enjoying a last hurrah. Bill Edrich, Joe Hardstaff and Norman Yardley were amongst them. There was a series of five unofficial Tests and fortunes ebbed and flowed. The Englishmen won the first two matches before being pegged back to 2-2. After dismissing their visitors for 130 in the first innings of the decider the Indians would have had high hopes of taking the series but they were dismissed twice for 131 and lost easily enough in the end. Vinoo with 57 in the second innings was the only Indian batsman to show any real resistance to the English opening bowlers, Arthur Wellard and George Pope.

It may have been different had Vinoo been selected for the first match as well as the succeeding four. As it was The Cricketer was able to describe him as the outstanding player for India. Mankad proved himself to be an exceptionally good all-round cricketer. He rarely if ever failed with the bat, was a remarkably accurate left hand bowler, and the manner in which he caught Edrich at short leg in the match at Calcutta was an astounding effort. A great cricketer. The numbers backed up that judgment. Vinoo topped both batting and bowling averages. His 376 runs came at an average of 62.66 and his 15 wickets cost just 14.53. Those performances are the more remarkable when it is borne in mind that Vinoo was just 20 at the time. Despite those tender years Tennyson for one expressed the view that Vinoo would have been an automatic selection for a World XI of the time.

After the first defeat in the representative matches Vinoo had won his place with a fine performance for Jamnagar against the tourists. The home side won by 34 runs and Wisden waxed lyrical about the all round contribution of Amar Singh whilst, curiously, failing to mention at all Vinoo’s 62 and 67* followed by bowling figures of 4-55 and 2-56. Proof positive if ever it were needed that there is more glamour to being a fast bowling all-rounder than a spinning one.

Having won his place Vinoo was, as The Cricketer noted, a model of consistency but his performance in the fourth match of the series, won by India by an innings, is worthy of special mention. India won the toss and batted. They scored a modest 263, built around Vinoo’s 113 not out from first drop. When the Englishmen batted it was Amar Singh again who had the stand out figures with eleven wickets in total, but he was superbly supported by Vinoo who went for barely two runs an over as he took 3-18 and 3-55 to go with his unbeaten century.

It must have been as frustrating for Vinoo as for every other top class cricketer to lose his best years to the war and he was doubtless delighted to finally have the chance to make a Test debut in 1946. In some ways after six years of war the result of the Tests was less important than the fact that they took place at all. The series was won comfortably enough by England. They took the first Test by ten wickets and were one wicket away from taking a 2-0 lead in the second before rain ruined the third and final encounter. Vinoo’s contributions to the Tests were unspectacular, but there were sound innings in the first and third Tests, and a long spell in the second which brought him 5-101 in 46 overs.

On the tour as a whole Vinoo became only the second tourist to do the double, and indeed only one other man achieved the feat in that long forgotten first English post-war summer. He comfortably headed the tourists’ bowling averages with 129 wickets at 20.76. The next highest haul of wickets was the 56 of Lala Amarnath and Vijay Hazare. With the bat there were four men with higher averages but Vinoo scored 1,120 runs at 28.00. John Arlott’s view was that by the end of the tour there was little doubt that he was the best slow left arm bowler in the world.

Next up for India was their first trip to Australia to play a full five Test series against the side that a few months later were to become Donald Bradman’s Invincibles. In the circumstances the fact that they lost 4-0, three times by an innings, was only to be unexpected. Again however Mankad did well on the tour as a whole, topping the bowling averages and being well up with the bat. He scored a century in each of the Melbourne Tests, but his aggregate and average suffered from a number of low scores as well. His dozen wickets cost him more than 50 runs each, but he bowled many more overs than any of his teammates, and at least managed to keep the Australian batsmen relatively quiet.

It was during this tour that the word ‘Mankading’ was coined, Vinoo twice running out Bill Brown whilst backing up. It is not entirely clear whether Brown was warned on both occasions, although he himself maintained that he was, and neither he nor, more notably, Bradman ever did anything other than support Vinoo’s actions. It might be thought that such an action was, whether justified or not, the action of a somewhat taciturn and perhaps not particularly likeable individual. But it seems that Vinoo was anything but that, Lindsay Hassett writing at the time I like Vinoo Mankad – all members of the Australian team like him as a man. He is cheery. He has skill that makes him a worthy opponent and he has a philosophy that prevents him from losing his balance despite hard luck that comes his way.

One achievement of Vinoo’s that will remain unique is his having played a major role in India’s first ever Test victory. In 1951/52 an English side travelled to India under the leadership of Lancashire’s Nigel Howard. In truth the Englishmen were probably weaker than the side led by Tennyson a generation previously. The only names that resonate today are those of Brian Statham and Tom Graveney, but these have always been official Tests. The first three matches were drawn before England took a 1-0 lead in the fourth. India’s victory to square the series was a resounding one by an innings and nine runs. England’s first innings was 266. There was no devil in the wicket, as India showed when they replied with 457-9 before declaring. But the Englishmen were tied in knots by Vinoo who bowled 38.5 overs. His figures were 8-55. As England batted again in search of 191 to make India bat again they again had to contend with a long spell from Vinoo. This time he had to share the wickets with off spinner Ghulam Abbas but a match haul of 12-108 was the key to the victory.

When India followed their visitors back to England for a four Test series in the summer of 1952 they knew they faced a much tougher assignment against the full strength of their hosts. The side was desperately short of experience. Vijay Merchant, their finest batsman, decided to retire after the home series and none of Mushtaq Ali, Lala Amarnath and Rusi Modi were selected – the English experience of all of them would have been invaluable. Most striking though, and wholly unnecessary, was the absence from the party of Vinoo.

A professional cricketer Vinoo had been in a difficult position the previous November. He had an offer from Lancashire League club Haslingden for the 1952 summer, of a contract worth £1,000, a huge sum by the standards of the day. He would have preferred to play for his country, and approached the selectors. All he sought was a guarantee that he would be selected for the touring party, on which basis he would have turned Haslingden down. He didn’t get the assurance he sought, so signed his contract and was lost to India. The story became more ridiculous as skipper Hazare managed to persuade the club to release Vinoo for the Tests, but the board refused to sanction the agreement so there was no Vinoo for the first Test at Headingley.

There have been worse defeats for India than that at Headingley, but this is the famous match when at one stage their second innings stood at 0-4, their batsmen having no answer to the cut and swing of Alec Bedser, and the sheer pace of the young Fred Trueman. It was clear that something had to be done, and the board relented and Mankad’s release obtained for the remaining three Tests. At Lord’s England went 2-0 up, their victory by eight wickets looking comfortable enough, but they had to get past a remarkable one man show by Vinoo.

Hazare won the toss and batted and India got to lunch with Vinoo and Pankaj Roy still together. Roy had batted stubbornly but Vinoo had played with considerable freedom, hitting leg spinner Roly Jenkins for six after just half an hour. Once he departed at 106 no one other than Hazare showed any resistance and India subsided to 235 all out. In reply England put up 537. Vinoo bowled as many as 73 overs, almost 30 more than any of the specialists, and took 5-196. With 302 required just to make England bat again the situation was hopeless but it was no fault of Vinoo’s that India lost. He scored 184, and was utterly dominant. In a partnership of 211 with his captain Hazare, a very fine batsman himself, contributed only 49. No one else could help much though and England needed only 77 for victory. Still Vinoo didn’t make it easy for them. He was brought on after just one over and then bowled unchanged for the rest of the innings, sending down 24 overs at a cost of just 35 runs as he and Ghulam Abbas made England fight for every run.

The rest of that series was an anti-climax for Vinoo, but he touched the heights again a few months later in Pakistan’s inaugural Test when he took 8-52 from 47 overs in the first Pakistan innings followed by 5-79 in the second. The series itself proved not to be quite the pushover India might have expected, as although they won 2-1 the Pakistanis fought hard. By the time the return encounter took place in 1954/55 Vinoo was captain. The first series ever played in Pakistan was the first ever to feature five draws. Fear of defeat was uppermost in the minds of the players of both sides and Vinoo’s captaincy was uninspiring. His batting and bowling were unremarkable as well.

From his average of barely 10 against Pakistan Vinoo managed a Bradmanesque 105.20 in the home series against New Zealand twelve months later. Freed from the cares of captaincy, and with Fergie Gupte having assumed the mantle of the side’s main spinner, Vinoo was free to concentrate on his batting and there were two double centuries. It is true that the New Zealander’s bowling was weak, and five other Indians all managed to average more than 50 in the series, but it was still a notable achievement, particularly his 231 in the final Test which contributed to an opening partnership of 413 with Roy, a record not bettered for more than half a century.

There were two more home series in which Vinoo played a part, against Australian in 1956/57 and West Indies the following year but, as he approached and passed 40 he was not quite the player he had once been and his rewards were modest. Vinoo’s final First Class outings were in India in November 1963. Shortly before that he had wound up the league commitments in England that had begun more than a decade earlier when he had done the double for Castleton Moor in the Central Lancashire League, and done so by such a margin that he set a record only broken when Frank Worrell arrived in the league. He continued with much the same success for Haslingden between 1952 and 1955 before moving back to the Central Lancashire League with Stockport and then on to the Bolton League.

Part of the duties of professionals in those days was to coach youngsters and that was a part of the job that Vinoo had a great deal of time for. In an era when most coaches stuck rigidly to the contents of the MCC coaching manual he was a man who bucked the trend, encouraging youngsters to follow their instincts, and making adjustments only when necessary. He was happy in Lancashire as well, and hoped the county might one day seek his services, but in those days Lancashire had plenty of quality in the spin department, and neither they nor any of the other counties ever made an approach.

Back in India three more Mankads have played First Class cricket although only elder son Ashok played Test cricket. Ashok was a top order batsman who made a decent start to his Test career when first capped as a 23 year old against Australia, but he never kicked on despite being given a number of opportunities to do so. As to what Vinoo did to occupy his time after retiring from the game he certainly did some coaching and, according to his biographer he worked for a ‘renowned commercial organisation’ in Bombay, but that is as far as he enlightens his reader. Sadly Vinoo was not to be blessed with great longevity. He died from a heart attack in 1978 at the age of 61.

Leave a comment