The Years of the Supercat

Martin Chandler |

In common with every Lancashire supporter, young and old, I remember the feeling of anticipation before the start of the 1969 cricket season. We already had the hugely popular Indian wicketkeeper/batsman Farokh Engineer in the side, and now he was to be joined by Clive Lloyd. In those days of course there had only been 35 years of hurt, and neither of those magnificent international cricketers were destined to stop that extending to 77, but they did usher in a period of great success in one day cricket and that, certainly for younger supporters, was enough for the time being.

What I cannot now recall, nor can I work out the answer to the question, is just why I was so excited at Lloyd’s arrival. I was only eight years old, so I cannot see how I would ever have seen him play. He wasn’t in the 1966 West Indian touring party, and I’ve never in my life been to Haslingden, the small town in the Rossendale Valley who played in the Lancashire League, and for whom he played with great success in 1967 and 1968. He was the leading runscorer in the league in both seasons, and in 1968 by a long long way, but any ripples of news emanating from the Lancashire League seldom got as far as where I lived on the Fylde Coast.

At that time televised Sunday cricket had just begun on the new BBC2 service. In 1969 that was to be used to showcase English cricket’s first 40 over competition, the new John Player’s County League, but in 1968 the cameras had followed the Rothman’s International Cavalier’s XI around the country. I would have seen Lloyd then, but looking back at the scorecards now he wasn’t particularly successful with the Cavaliers.

I had by this time just started reading the back pages of the Daily Telegraph, so it is just possible I might have read about Lloyd’s two match-saving Test centuries against England in the Caribbean in 1967/68, or his match-winning one in Brisbane a few months later, but I doubt it. At that age I wasn’t particularly interested in the idea of Test cricket that took place overseas, even if England were involved, and in any event those series took place in the football season!

So I suspect it must have been no more and no less than the hype that surrounded the arrival of Lloyd that did the trick, although the accuracy of that was doubtless questionable. Even Wisden, in its 1969 edition, described him as an all-rounder. In his early days he did bowl some right arm medium pace, but to categorise him as an all-rounder was certainly stretching a point.

I did get to speak to Lloyd once, at a benefit match in his early days with the county, but sadly I no longer have the scorecard he and a number of his teammates signed for me. In the way of small boys I just thrust the pen into his hand, with the scorecard. While waiting my turn I had thought of lots of searching questions to ask him, but when I got to the front of the constantly moving snake of youngsters all I could blurt out was to ask what number he was batting. It was a good job he smiled at me as he pointed to his name on the card. If, as I deserved, he had rolled his eyes and tutted I would probably have been traumatised for life. I had been at the back of the queue and I remember still that, as he stood up to wander into the rudimentary pavilion at Lytham CC, I couldn’t believe how tall he was. The books say he was only 6′ 4”, but he seemed so much taller than that. It might have just been my own relative lack of height in those days, coupled with my awe of and unfamiliarity with my heroes, but Lloyd seemed twice the size of anyone else on the ground.

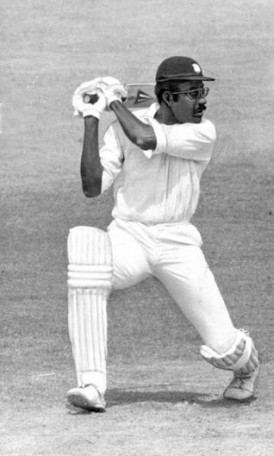

Watching Lloyd go out to bat was a compelling sight as well. There was none of the sprightliness and spring-heeled haste that many batsmen seem to show. For Lloyd it was just a leisurely amble, doubtless exaggerated by his slightly round-shouldered posture and, above all, the way he generally dragged his bat along the ground behind him. I had never seen that before, and only noticed it again when Channel 9 introduced their Daddles the Duck graphic in 1977 – I don’t suppose for one moment that whoever designed Daddles had Lloyd in mind when he or she did so, but I could never get it out of my mind that it was disrespectful to one of my favourites, and I never approved.

As a child I was always quite stoical in outlook. I certainly wasn’t amongst the many of my age who, by all accounts, would often hide behind the sofa when the more traumatic moments of Dr Who were being broadcast. That said I quickly developed such a fear of the beginning of a Lloyd innings that it wasn’t just a case of adopting a position behind the furniture. For me it was right up to the top of the garden and into the potting shed for ten minutes. Lloyd was an awful starter. His feet were leaden and, generally, rooted to the crease, and it always looked like he was going to be out any minute. As his innings began his timing would normally be non-existent and all those things, coupled with the fact that I was always so desperate to see him do well, were just too much for me. Sometimes it took him several overs to get going properly, but the first three or four were by far the worst.

Then suddenly it would all come together and there would be one delivery when the tide turned, and Lloyd’s feet would get in the right position and the timing would be such that the ball would get to the boundary in a flash. After that it was a completely different game and only a magnificent catch, a slice of bad luck or a very good piece of bowling would bring the entertainment to an end. It was spectacular stuff as well, as Lloyd would generally hit the ball very hard indeed. That said he could be subtle, and I remember occasions when what appeared to be clips to leg for a single turned out to be so well timed that they went over mid-wicket for six. In 1976 Lloyd equalled Gilbert Jessop’s long-standing record for First Class cricket’s fastest double century. It is a record that Ravi Shastri has subsequently taken as his own, and I am not convinced circumstances then were not a little contrived, but that is not really the point – the reality is that Lloyd could and often did change the course of a cricket match in a very short time.

Those who remember Lloyd’s later career will doubtless recall a fine slip fielder. His hands were huge and little evaded his enormous reach. As a young man however his job in the field was to patrol the covers and he was the best there was. Writers and commentators talked of his feline grace, and they christened him Supercat. Personally I felt the way he wandered around, apparently aimlessly, before swooping on the ball and returning it to the stumps, all in the same movement, was more reminiscent of a bird of prey, but perhaps that is a distinction without a difference.

As for Lloyd’s bowling in fairness to the cricketer’s bible, which seldom makes mistakes, he did get a few wickets occasionally, but in 110 Tests he took just 11, and he never got a five-for in a First Class match. But his bowling was important to me so I do remember it well. The reason for its elevated status in my corner of Lancashire was that it was something I could copy. After all even if I had batted left handed my inability to hit the ball off the square would inevitably hamper the possibility of a comparison. And as for his fielding in the covers – well shall we just say I had more chance of batting like him. But that lazy lope into the wicket and the classical delivery stride that propelled his right arm medium pace deliveries towards the batsman struck me as eminently worth copying.

In December 1971, while playing for a Rest of the World side in Australia Lloyd dived for a catch in the covers and ended up paralysed for some time. The fears that his career would be over proved to be unduly pessimistic, but it was that injury that turned the great cover point into a very fine slipper, and perhaps it even prevented Wisden’s error about his all-round prowess being corrected by the passage of time.

Lancashire won the Sunday League back in 1969, and perhaps elation at that meant that Lloyd’s relatively poor performance could be safely overlooked. He had been with West Indies for the first half of the summer, but he only averaged 35 and recorded just a solitary half century in the three Tests. For Lancashire he averaged just 30, and 25 in List A matches, and he was out for a duck in his first Roses Match – I suspect that his first record breaking double century at Swansea, coupled with the memories of those who had watched him in the Rossendale Valley, were what kept the legend alive.

The following season, 1970, Lancashire retained the Sunday League but, more importantly, took the first of three consecutive Gillette Cups. In the 21st century it is very difficult to convey just how important the Gillette Cup was in those days. It was the domestic game’s big day out and while from 1972, with the advent of the Benson and Hedges Cup, there were two such events each summer the end of season final was by a distance the more important of the two. It always sold Lord’s out, and every delivery was shown on either BBC1 or BBC2.

Over the course of that hat-trick of victories Lloyd made a significant contribution to each and every Lancashire win, a dozen games in all, and the culmination was his Man of the Match winning performance in the 1972 final against Warwickshire. The West Midlands county batted first and Lancashire immediately had a problem. They had a pair of England opening bowlers in Peter Lever and Ken Shuttleworth, but both had been woefully out of form all season and they were left out of the side for the final. Despite concerns over his bowling after that frightening injury in Australia Lloyd took the new ball with Peter “Leapy” Lee and reeled off his twelve overs in a single spell for just 31. Lancashire were set 235 to win in their 60 overs. To modern eyes that seems a very modest target but no side batting second in a final had ever scored so many before, and when after ten overs Lloyd came in at 26-2 it looked like Lancashire might at last fail. Eight overs later Lloyd was on six, having scratched around as only he could, but the longer he struggled on the more it looked like it would be his day. Then without warning there was a straight drive that would surely have taken bowler David Brown’s hand off had he got down to it, followed immediately by a hook for six, and the game changed irrevocably. Eventually at 219 a young Bob Willis removed Lloyd for 126, and as Farokh Engineer followed four runs later hope flickered briefly for Warwickshire, but Lancashire quickly snubbed that out.

There was no Gillette Cup glory for Lancashire in 1973, but given that Lloyd was on duty with the West Indies that summer and unable to appear for them, it was perhaps hardly surprising. There were however another hat-trick of finals between 1974 and 1976 although only once, in 1975, was there, courtesy of Man of the Match Lloyd, another trophy. In 1974 he was instrumental in getting the Red Rose to the final but, after the big day was rained off, although his was the top score on either side on the reserve day it wasn’t enough to stop Kent lifting the trophy. In 1976, when Lancashire played poorly in losing to Northamptonshire, Lloyd was busy elsewhere all summer, making Tony Greig eat his words.

In the Championship Lloyd soon left behind his travails of 1969 and was a consistent run-scorer for Lancashire right up until 1986. After his initial disappointment he was particularly severe on Yorkshire, and averaged almost 50 against the White Rose with six centuries. It should be borne in mind that, particularly in the 1970s, the combination of poor surfaces and Roses games frequently being played under leaden skies, make those figures particularly impressive. Lancashire were never, in the latter part of Lloyd’s career with the county, as strong as their supporters would have wished them to be and there were some bleak summers before, in 1986, Lloyd finally decided that at the age of 41 that was to be his last. He took back the poisoned chalice of the captaincy but despite averaging nearly 50 with the bat himself in the limited number of Championship games he played in he could not drag the county out of the doldrums and we were 15th. There was nearly a fairytale ending though as for the first time since 1976 Lancashire fought their way through to Lord’s for the final of what Lancastrians will always call the Gillette Cup (although it was by then known as the Nat West Bank Trophy). Sadly they didn’t score enough runs, and Lloyd suffered the indignity of being adjudged lbw to Dermot Reeve for a duck. It was my fault really, as I was reminded of my childhood favourite The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe. I was just too old to be allowed access to a magic potting shed as Lloyd came into bat, and in the five minutes my back-up plan of nipping down the road for a pint of milk took up, Big Clive had come and gone.

For me, and many of my contemporaries Lloyd’s achievements with Lancashire are all that is required for his cricketing immortality, although in truth I would have to concede that for most it will be what he brought to the game during his tenure as captain of the West Indies, so it is a facet of the man that I cannot disregard.

Lloyd made his Test debut at 22 in December1966 against India at the Brabourne Stadium. He went on to play 110 times for West Indies over the next 19 years and his record is, on the whole, remarkably consistent. He disappointed in the three series he played against New Zealand, but that apart he seldom failed with the bat, and as he got older he seemed to get better. His overall career average was a highly respectable 46.67, but over his final 32 Tests he averaged more than 61.

The captaincy came Lloyd’s way in 1974 and he was at the helm, a brief hiatus during Kerry Packer’s World Series Cricket apart, for a decade, a period which saw the natural order of things in the game of cricket change forever. There was a run of 26 Tests unbeaten, and one of eleven consecutive victories. His successor, Vivian Richards, summed up his achievements When he took charge he led a team that was divided by island rivalries and unable to discipline itself when things were going wrong. At the end of his reign Clive handed over to me the most powerful and united team in the world, maybe in the history of the game.

Lloyd’s tenure began with a 3-2 win in India, never a simple task and certainly not easy in those days when the great spin quartet of Bedi, Prasanna, Chandra and Venkat were close to their peak. It was then to England and the first World Cup in 1975. In the Lord’s final Lloyd was his usual reliable self. He came in at a time of crisis, played and missed painfully for a few overs, and then went on to score an unforgettable match-winning century.

A tour of Australia followed in 1975/76 and West Indies would have begun it with a degree of confidence, which would doubtless have been increased as they secured a superb win in the second Test at Perth. However despite Lloyd himself averaging more than 46 the series was lost 5-1. As Richards later said We were slaughtered …Lillee and Thomson ran through us and it was like fighting against a tornado. We fell apart and Clive realised that he’d been shown the way to play Test cricket. Australia played hard, with fearsome fast bowlers, brilliant close fielders and courageous batsmen. We learned a hard lesson.

As soon as Lloyd’s men returned they had a home series against India to negotiate and it was in that series, after his spinners allowed the Indians to successfully chase down 403 for victory for the loss of just four wickets in the third Test, that Lloyd realised he must pin his hopes on pace and the fourth Test of the series became the Battle of Sabina Park, where India had as many as five men unable to bat in their second innings due to injury. And then it was 1976, and Tony Greig’s avowed intent to make Lloyd’s men grovel – the best one can say for Greig is that looking back some England captains fared even worse than he did in the years that followed.

There was one series, that in New Zealand in February 1980, that ended in defeat for Lloyd’s West Indies, but that apart it was success all the way. Inevitably there were a few detractors from time to time, and Lloyd can be very prickly if defending himself and his men. There was Bishen Bedi for one, and the fall out and ill-feeling from the Battle of Sabina Park lasted for years. There was criticism of the barrage of bumpers which Brian Close and John Edrich had to endure at Old Trafford in 1976. Lloyd was also defensive about that controversy reasoning, quite rightly of course, that it was the umpires and not the English press who were the game’s arbiters of fair play. He also maintained, again correctly that Greig, had he had the means to do so, would not have hesitated to use the same tactics against the West Indian batsmen. Often forgotten these days is the criticism of Lloyd’s captaincy that came from England’s Mike Brearley, who suggested rotating fast bowlers every half hour was hardly a taxing tactical exercise, but it is a view that Brearley has subsequently admitted he regrets expressing, so perhaps it is best left in the past.

Speaking personally, while I can naturally appreciate all that Lloyd achieved in the international arena, he remains first and foremost a great Lancastrian, and a man who lit up my childhood and is in no small part responsible for the passion for the game of cricket that has stayed with me all my life. I will not see his like again.

Disappointing lack of Simon tbh.

….but still a good read 🙂

Comment by NZTailender | 12:00am GMT 22 February 2012

Nice article about an underrated player and Great leader.

Comment by kyear2 | 12:00am GMT 23 February 2012