The Shaky Isles’ Finest Southpaw?

Martin Chandler |

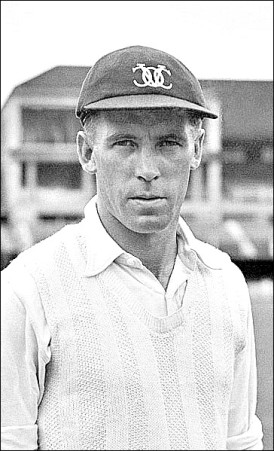

Last year marked exactly one hundred years since the birth of Martin Donnelly. The diminutive left hander, nicknamed ‘Squib’ by his teammates, does not crop up in too many conversations on the subject of the game’s great batsmen, but he was no ordinary player. CB Fry, a great eccentric but decent judge of a cricketer, described him in 1949 as the best left handed batsman he had seen, and CB saw plenty of Frank Woolley and Clem Hill.

One problem was that cricket only had a glimpse of Donnelly’s talents. The Second World War saw to it that he lost seven years, and after four matches for Warwickshire in the 1950 County Championship commerce claimed him and, not yet 33, Donnelly consigned his cricket career to history. Another factor in the Donnelly legacy not being what it should be is that those who would normally expect to champion his cause more vociferously, his countrymen, saw so little of him. He played just 13 times in First Class cricket in the country of his birth.

Donnelly was born in a small rural town, Ngaruawahia in Waikato. When he was six his family moved to Eltham in Taranaki. In cricketing terms he might have played for Central Districts, but it was 1950 before the Plunket Shield embraced that team. The family farmed their own land and life was far from easy as although Donnelly seems to have had a largely happy childhood the family was certainly touched by tragedy with some frequency. There were as many as thirteen children, although only eight survived to adulthood. The eldest son died at nine, another at twelve months and Donnelly’s twin brother died in a flu epidemic in 1918. There were two still births along the way and then, when Donnelly was ten, his father died as well meaning his older siblings played a big part in his upbringing.

As a batsman Donnelly had the worst possible start to his cricket career, bowled twice for a duck in his first match by the same bowler. It could only get better, and did very quickly and as a schoolboy Donnelly enjoyed many more days of success than of failure. He was also a fine tennis player, eventually having to choose cricket over that game, and in the winter months he excelled at Rugby. He became a little more circumspect after the war, but certainly in his youth he was a crowd pleaser with the bat, albeit one who based his success on a sound technique. There were no particular strengths, and no particular preference for any type of bowling although, writing in the 1950 edition of Wisden, ‘Crusoe’ Robertson-Glasgow described one signature shot; flicking the seemingly accurate ball to the leg boundary wide of mid on, going on to observe that not even Bradman played the shot with such impudent certainty.

Whilst still at school an 18 year old Donnelly was selected to play for Taranaki against a touring MCC side led by Surrey’s Errol Holmes. In the first innings he was bowled by the Middlesex and England leg spinner Jim Sims. He only had four to his name at the time and gave Sims the charge, failing to pick the googly. After a little coaching from the Englishmen he top scored with 49 in the locals second innings and batted so well that Holmes alerted the New Zealand Cricket Council to his talents.

A year later Wellington’s selectors, apparently influenced by Holmes’ opinions, chose Donnelly for a game against Wellington at Eden Park. In a match in which four men made centuries Donnelly’s contributions of 22 and 38 do not look particularly special, but the watching press were impressed by the way he batted, and particularly so by the manner in which he patrolled the outfield. There was no reason to expect Donnelly to be selected for the Test match that took place against England six weeks later, but if the selectors were seriously thinking about taking Donnelly to England in 1937 it looks a little odd that a place wasn’t found for him in one of the other two sides who played against the tourists.

Whatever the thinking at the time was Donnelly, after just that single First Class match and not yet 20, did find himself boarding the Arawa in late March of 1937 as a member of the second New Zealand party to embark on a Test series in England. Not without a few mishaps along the way Donnelly emerged from the tour with a great deal of credit, second only to Mervyn Wallace in the tour averages with 1,414 runs at 37.21 and described by the editor of Wisden as a star in the making.

In the lead up to the first Test Donnelly, in the second innings against Lancashire, was dismissed for the first duck in his First Class career. In the next match, against Nottinghamshire, he had just one visit to the crease and it was nought again. When, in the first innings of his first Test, at Lord’s, he was out without scoring for a third consecutive time there must have been a real danger of the young man losing his confidence completely. He couldn’t have chosen a more difficult time to begin his second innings. New Zealand were in trouble, 146-7 with an hour to go. The Surrey pace bowler Alf Gover tested the youngster out with a bouncer, which was coolly hooked to the boundary. After that Donnelly and his partner, Jack Kerr, who was struggling after suffering a blow on the head in the first innings, calmly batted out time Donnelly only losing his wicket, for 21, to the very last delivery of the match.

After that important innings at Lord’s Donnelly went on to score at least a half century in each of his four appearances before the second Test. In the game against a Yorkshire attack led by Bill Bowes and Hedley Verity he came within just three runs of recording his first century. The second Test was the only one of the three that England managed to win, by the seemingly comfortable margin of 130 runs, but the New Zealanders were in with a real chance at one point. It all started well enough with England’s openers putting up a century stand, and a young Len Hutton going on to make his first test hundred. England would have been happy enough with their first innings lead of 77, but when they slumped to 75-7 they were in real trouble. Even after Les Ames, Freddie Brown and Jim Smith, thanks in part to some lapses in the field, lifted the final total to 187 the New Zealand target of 265 was still achievable. Sadly for them however the long fingered Gloucestershire off spinner Tom Goddard found a pitch to his liking and after going wicketless through 18 overs in the New Zealand first innings he took 6-29 in less than 15 overs. In the first innings Donnelly had made just four, but in the second innings, after the openers had put on 50, he was the only one of the remaining batsman to resist, remaining unbeaten on 37 at the fall of the last wicket.

The elusive century came immediately after the second Test when, against Surrey, Donnelly scored 144 in the first innings, a knock which paved the way for one of what proved to be only four victories over the counties. Interestingly an old admirer, Holmes, not at that stage of his career a regular bowler, dismissed him in both innings, two of only five wickets he took all summer.

Thanks to the weather New Zealand were also able to draw the third Test at the Oval. Most of the first day was washed before, on the second, New Zealand went on to total 249. Donnelly was one of three New Zealanders to manage a half century and, with 58, his was the highest. There was time enough for England to go past New Zealand and declare with seven wickets down and bowl them out for 187 but at that point there was only time for another ten overs, so England’s pursuit of 183 for victory never really got going. They were 31-1 when the umpires lifted the bails.

The New Zealanders left England at the end of September, most of the party boarding the Orontes at Tilbury, the ship that five years before had taken Douglas Jardine’s England side to Australia. A handful, including Donnelly, took up the management’s alternative offer of allowing the players to travel to Paris to see the International Exhibition and then join the ship at Toulon. As a young, single man perhaps it is no surprise that he did so.

On the way home the New Zealanders stopped off to play South Australia and Victoria, with little joy there for Donnelly. Back home he set off for Canterbury University College where he was until the outbreak of war. His Plunket Shield performances in 1937/38 were modest, as he scored just 192 runs in three matches. He did however reach 50 three times in the three games – no other Wellington batsman managed even a single half century.

Switching to Canterbury for the following season Donnelly had a lean time, not passing 50 at all but the following year, promoted to open the innings, he did much better, finally making his second First Class century, and adding innings of 97 and 78 as well to average 75.50 for the season. After that the Plunket Shield was suspended for the duration of the War. There was however a one off match in January 1941 between Wellington and Canterbury. Donnelly turned out for the former and scored 68 and 138*.

Donnelly chose the Army for his military service. He joined as a private soldier, trained in the cold of the North Island before, in early 1943, being posted to the heat of the North African theatre where he ended up as a Major in Italy. Finally, in May 1945 and the war in Europe over, he was posted to Kent to join the Prisoner of War Repatriation Unit. There were only eleven First Class matches played in England that summer. Donnelly appeared in two. He scored 133 and 29 for the Dominions against England at Lord’s and 100 and 86 for a New Zealand Services XI against HDG Leveson-Gower’s XI at Scarborough.

In October of 1945 Donnelly went up to Oxford to study History. The 28 year old had a superb summer in 1946. He passed his century six times and averaged 52.77. There was a century against the touring Indians, and a remarkable 142 out of 194 in the Varsity Match at Lord’s. Oxford won, and no other player on either side got even as far as fifty. He carried his form at the wicket onto the Rugby field that winter, so much so that in February 1947 he became one of the select band of double internationals when he was selected for England to play Ireland in Dublin. Normally a fly half Donnelly was played out of position in the centre and in winds that did not drop below 60 mph was part of a 22-0 defeat, at the time Ireland’s record winning margin over England. It was the only occasion on which Donnelly was capped.

The batsman’s summer of 1947 once more saw Donnelly as Oxford’s leading batsman. He averaged 62.00. His highlight of the season was an undefeated 162 in the Gentlemen’s first innings of the traditional fixture against the Players at Lord’s. There were four other centuries and Donnelly was named one of Wisden’s Five Cricketers of The Year in its 1948 edition.

After two years Donnelly completed his studies at Oxford and joined Courtalds, then a major textiles manufacturer. He was able to negotiate an arrangement where he would be able to play for Warwickshire in the summer of 1948 and, assuming he was selected, for the New Zealanders in 1949. In the event what was to prove to be Donnelly’s only full season with Warwickshire was a disappointment. He failed to score a single century for the county and without his only big innings of the summer, an unbeaten 208 for the MCC against Yorkshire in the Scarborough festival at the end of the season, he would have averaged only 27. The reason for his loss of form seems most likely to be a certain impetuosity brought about by being used to the superb wickets that existed in The Parks at Oxford. The more sporting wickets at Edgbaston and elsewhere around the counties tended to punish Donnelly. Inevitably Lady Luck would also have played a part and any batsman who suffers the fate, that Donnelly did at Lord’s in the Championship knows that fortune is not favouring him. Having reached 55 a delivery from left arm spinner Jack Young hit Donnelly’s foot, looped over the stumps and spun back a foot to bowl him. A stronger message that it wasn’t going to be his summer it is difficult to imagine.

Despite his poor performances in 1948 there was never any real doubt that Donnelly would be selected for the 1949 touring side under the captaincy of Walter Hadlee. His previous achievements and more importantly his knowledge of English conditions were the reasons for his inclusion. The ‘49ers’ were a strong side. They drew all four Test matches and lost only once, ironically enough in the Parks of Oxford University where Donnelly recorded his only duck of the summer. On the other hand as many as thirteen First Classes matches were won. Had Donnelly’s Warwickshire teammate Tom Pritchard, a fast bowler from Taranaki who in 1948 took 172 wickets at 18.75, been available to spearhead their attack with the veteran Jack Cowie then their achievements would doubtless have been more impressive still. For Donnelly any concerns that his previous year’s disappointing form would continue were soon allayed. On the tour as a whole he scored 2,287 runs at 61.81. In the Tests there were 462 runs at 77.00.

In the first Test New Zealand were struggling at 80-4 in reply to England’s 372 when Brun Smith joined Donnelly. They added 120 before Donnelly was dismissed for 64, by which time order had been restored and England never got back on top. The second Test at Lord’s was undoubtedly Donnelly’s finest hour. England won the toss and batted first and had much cause to be grateful for the efforts of Denis Compton and Trevor Bailey who added 189 for the sixth wicket. In reply to 313 Donnelly then scored 206 as the New Zealanders took a first innings lead of 171. This was just the sort of situation where Pritchard may have made a difference as England lost just a single wicket in wiping out the arrears and comfortably batted out time.

The third Test was much like the second, with the boot on the other foot. The New Zealanders elected to bat first this time, and were bowled out for a relatively modest 293, Donnelly top scoring with 75. In reply England took a lead of 147. New Zealand were not to be intimidated however, and a Bert Sutcliffe century and 80 from Donnelly made sure that the advantage could not be pressed home. The fourth and final Test was similar again, although at least this time New Zealand did have a few anxious moments in the third innings. Their total this time after winning the toss and batting was 345 with a modest 27 from Donnelly. The England lead was 137 and four wickets were lost in clearing that and, just briefly before a 21 year John Reid settled in for his 93, it looked like England might break the deadlock.

In January 1950 Donnelly got married in London. In the summer Courtaulds gave him the time to play four matches for Warwickshire, which brought down the curtain on his career in England. It would have been of some comfort to him that at last he managed to show the Edgbaston supporters what he could do when he finally managed a century in Warwickshire colours. It was doubtless all the more satisfying that the opposition were Yorkshire, and an attack comprising two England bowlers, Alec Coxon and Johnny Wardle, as well as two others who would go on to play Test cricket, Eddie Leadbeater and a young pace bowler by the name of Trueman.

Before the season’s end Donnelly and his bride were on the way to Australia so that Donnelly could take up the position of General Sales and Marketing Manager for Courtalds Australia. He settled in Sydney and four children, three sons and a daughter, blessed the Donnelly family. In time he became a Director of Courtalds, a position he retained until 1970 when, faced with the choice of relocating to Melbourne or starting something new he chose the latter. For a few years he was a partner in a mail order business and held an agency for a New Zealand company before, in 1976, he joined the publishers Hodder and Stoughton.

There was some cricket for Donnelly in Australia, generally for I Zingari. Twice, in December 1956 and February 1961 he went back to New Zealand to play in one off three day matches. The first, not ranked as a First Class match only because there was no toss, pitted the ‘49ers’ against the current Wellington side. The youngsters were all out for 281, but the game started to look like a mismatch when the 49ers were skittled for just 82, Donnelly failing to trouble the scorers. Following on however they made a much better fist of matters and Donnelly contributed a fluent 48. At the end Wellington were 73-4 in pursuit of 152, so honours even.

Five years later Donnelly travelled back across the Tasman Sea to play his final First Class match. For what was essentially an exhibition match it was an important event. The game was not doing well in New Zealand at the time, hence the visit of an MCC side for the best part of three months. Although there were three representative matches the most interest was generated by the match between the tourists and a side selected and captained by Charles Lyttelton, better known as Lord Cobham, the Governor-General of New Zealand. The MCC side was a strong one, only the captain Dennis Silk was never to win a Test cap. The Governor-General was an interesting character. He was no mug as a cricketer having played more than one hundred First Class matches before the war, although he was 51at the time of the match.

The scratch side contained the best of the current New Zealand players and Donnelly and Wallace. Two more veterans, Johnny Hayes and Geoff Rabone, also came out of retirement and Ray Lindwall and two West Indians, Cammie Smith and Gerry Alexander, also accepted invitations to play. A record crowd of 50,000 turned up at Eden Park over the three days so the tour certainly achieved its purpose. As for the match itself the tourists won an entertaining game by 25 runs. Donnelly, a little heavier than in his prime and greying at the temples, showed much of his old class even if his scores were modest, 15 and 25. He rolled back the years in partnerships with Sutcliffe in the first innings and Wallace in the second and in taking an excellent catch on the square leg boundary. Donnelly even reprised his occasional orthodox left arm spin and took a couple of wickets.

There is a scorecard on Cricketarchive showing Donnelly turning out for the Forty Club against Eton College in May 1961, so he was presumably in the UK on business, and that seems to be the end of his cricket in England. Donnelly remained settled in Sydney for the rest of his days and the first New Zealand cricketer to score a double century in a Test match died there in 1999, at the age of 82.

Leave a comment