The Man They Called ‘Bunter’

Martin Chandler |

I recall being very pleased when I was told that the 1970 South African tour of England had been called off. I would like to say that the reason was that even as a nine year old I was implacably opposed to apartheid, but if I am entirely honest that thought didn’t enter my head. What delighted me was that, the news being broken to me a few days after the announcement was made, was immediately learning that there was good news to go with the bad. In fact for this cricket mad youngster it was the best possible news. Instead of the South Africans there was to be a series against a Rest of the World XI, to be led by my great hero, the legendary all-rounder Garry Sobers.

The Rest’s side was a familiar one, all of its members bar three having taken advantage of the counties’ ability to specially register overseas players, something they had only been able to do since 1968. The three were all South Africans. I had heard of Graeme Pollock, lauded by all who had seen him from that time to this. That made little difference to me however as I was not a reader of cricket literature in those days. But my father had seen Pollock in 1965, and told me was as good a batsman as Barry Richards, and I knew from what I had seen of Hampshire’s overseas star that Pollock must therefore have been very special. The fact that Graeme’s name was familiar meant that so too was that of his fast bowling brother Peter. So the only man who was just a name to me was Eddie Barlow.

There were centuries for Barlow in the first two matches of the series. They were, particularly that in the second game, dogged rather than spectacular efforts, which is probably why they didn’t make a great impression on me. In the first England innings in the second match he took the first five wickets to fall as well. You couldn’t describe Barlow’s medium pace as gentle, as he bristled with aggression, but he wasn’t particularly quick, and that is doubtless why I didn’t really notice that either.

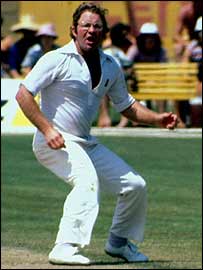

It was from the fourth match at Headingley that I have my most vivid memory of Barlow. In the England first innings, in which he took 7-64, he took four wickets in five balls including a hat trick. The hat trick delivery was the one that sticks in my mind, and the moment is preserved for posterity in the photographic section of the 1971 edition of Wisden. The effort Barlow put into the delivery was equalled by the celebration after the wicket was taken. The mode of dismissal was unremarkable, a straightforward bat pad catch to short leg. The catcher also caught my eye. Mike Denness, England’s twelfth man, had been pressed into service as a substitute. The look of disappointment on his face at catching his own man is palpable.

Having finally seen something I liked in Barlow he contributed little to the final match in the series and, his country’s sporting isolation having begun, he was not seen again in England until 1976 when, aged 35, he was brought in to captain a struggling Derbyshire side, a job he was to do for three seasons. I did however dig more into the career that Barlow had had. He did rather better than some of his teammates in that he did play in thirty Tests. At the point at which I first saw him he thought he had played 35, and was one of only two men, the other being another South African Aubrey Faulkner, to end a career with a batting average of more than forty (44.82) and one of less than thirty (29.30) with the ball. In 1972 however the ICC downgraded the Rest of the World games, so he lost that record as his bowling average went back above thirty, but his is still an impressive record.

With the bat Barlow could be dour, but at his best he was an aggressive stroke player. He had a low crouching stance with his bottom hand unusually low on the handle. Unsurprisingly given that, and his powerful forearms, his main strokes were the cut and the pull rather than classical drives. With the ball Barlow primarily swung the ball away from the right hander, but he could make the ball duck in as well. His most famous weapon however was a superbly disguised slower ball that caught even the best batsmen playing far too early.

Barlow’s grandfather was a Mancunian who took his family to South Africa to establish a plumbing business in the small harbour town of Mossel Bay, approximately midway between Cape Town and Port Elizabeth. As a youngster Barlow was short and stocky, thus earning his lifelong soubriquet of ‘Bunter’. In truth however, other than his glasses, hair and a passing facial resemblance Barlow was nothing like the Fat Owl of the Remove. He was a powerful athlete who excelled at rugby and cricket. After leaving school Barlow went on to read Geography at Wits University with a view to becoming a teacher, an ambition that was ultimately overtaken by the progress Barlow made on the cricket field.

On the rugby field Barlow was a centre. He did harbour ambitions to play for South Africa, but in those days the sport was dominated by Afrikaans speakers and, realising he had to make a choice, Barlow retired from rugby at just 22 in 1962. He kept going until then because he wanted to pit his skills against the 1962 British Lions. The 1955 Lions had given the Northern Universities a 32-6 mauling, but with Barlow opposing them the 1962 tourists were held to a 6-6 draw.

As a cricketer Barlow was invited to tour England in 1962 with a side of promising young players captained by the experienced Test player, Roy McLean, known as the Fezelas. The team went through a 21 match tour unbeaten, and won all three First Class matches. When they got home critics tried to downplay their achievements by criticising the quality of the opposition. A match was therefore arranged with a full Springbok side, effectively a trial for the forthcoming Test series against New Zealand. The Fezelas won, and the knockers were heard no more.

New Zealand had only ever won a single Test when they arrived in South Africa in October 1961. But the series proved to be an exciting and controversial one with much sledging, short pitched fast bowling and aggressive cricket from both sides. The final tally was a 2-2 draw with one Test drawn. Barlow’s performances for the Fezelas meant that he was one of as many as seven debutants in the South African side for the first Test.

Wisden’s summary is interesting, commenting; The batting find was a university student, Barlow – an opening bat who revealed an all too rare and refreshing desire to attack. He lived dangerously at times, and Dame Fortune was kindness personified, but the bespectacled lad has undoubtedly come to stay. As he progresses to maturity so he should become a tremendous force in the Springbok batting of the future. Opening the innings with Jackie McGlew Barlow was not dismissed for single figures once, but on the other hand in none of his three half centuries did he pass 67. His average for the series was 36, but the Wisden summary does not sound like the Barlow of 1970. His own explanation was that he was extremely nervous, and on debut in particular threw bat at ball at every opportunity.

Presumably selected for his all round abilities Barlow bowled a total of 43 overs in the first three Tests. He must have bowled tidily enough, as he conceded runs at only just three an over, but he didn’t take a wicket, and was not called upon to bowl in the final two Tests. Barlow was never out of a game of cricket though. He was always a fine slip fielder, and held five catches in the series.

South Africa’s next Test match action was two years later in Australia. The series is probably best known for the no-balling of Australian opening bowler Ian Meckiff in the first Test for throwing, but Barlow had happier reasons for remembering the series. In that first match he made his first Test century amidst all the controversy, 114. A duck in the second innings however meant that he kept his feet on the ground.

Another century followed in the second Test, and then in the fourth Barlow recorded what was to remain his highest Test innings, 201. His only misfortune was that in the same innings Graeme Pollock hit 175 in an innings of breathtaking brilliance – at least Barlow had the best seat in the house to watch Pollock’s knock, the non-striker’s end, as the pair put on 341. When the game started to drift and Australia began to look like they would comfortably hold on for the draw Barlow did something he was to become known for. He started to badger his captain to let him bowl.

After the blank he had drawn against New Zealand Barlow had taken four wickets in the first three Tests of this series, but was still by no means a frontline bowler. Eventually Trevor Goddard grew tired of Barlow’s pestering and threw the ball to him. He bowled five overs, took 3-6 and changed the course of the game as South Africa levelled the series. They might have won the final Test to take the series, but a last wicket stand of 45 between Tom Veivers and Neil Hawke for the last wicket in Australia’s second innings meant the South Africans needed 171 in 85 minutes, and the match was drawn. It could have been very different if they had required 126 in two and a half hours.

Their business in Australia over the South Africans moved on to New Zealand for three more Tests. The chilly conditions were not to their liking and the first two Tests were drawn. The South Africans had the better of both games, without being able to force home their advantage, but at least the fast bowling barrage that some felt might be the legacy of the 1961/62 series did not materialise. There was still controversy however as a result of the final Test. The New Zealanders successfully batted out the last day to earn a draw, in South African eyes purely as a result of poor umpiring decisions. After a 22 week tour Barlow and his teammates were delighted to get home.

A year on and South Africa had back to back series against England. MCC visited the Cape between October and February, and the Springboks were then due in England for the second half of the 1965 summer. After their performance in Australia the South Africans were expected to do well, but in the end lost the home series 1-0. England won the first Test at a canter, Barlow failing with the bat as he was dismissed for 2 and 0. In the first innings Barlow was bowled by Ian Thomson, a medium quick bowler from Sussex who played the only Tests of his career in this series. That is what Wisden and all the other record books say, and in his book on the series that is what South African journalist Charles Fortune describes.

For some time before his death in 2005 Barlow worked on an autobiography which was published posthumously. He describes being dismissed by Thomson for 2, but says he was caught at second slip, and that although he decided to walk due to the force of the appeal later saw his dismissal on film and that it was clearly a bump ball. Presumably Barlow was getting his memories mixed up. It was not the only time. Earlier in the book he had given an account of his century in the second Test in Australia in the previous year and told a story against himself. According to Barlow in the course of compiling his century he ran out both Trevor Goddard and Peter Carlstein. At one point he claimed to have received a message from the dressing room, in jest presumably although he does not say so explicitly, telling him not to bother coming in for lunch.

It is an excellent story, the sort that goes down well in after dinner speeches, but it does not stand up to even the slightest scrutiny of the scorecard. There were two run outs in the South African innings, but the men concerned were Colin Bland and Joe Partridge, and Barlow had already departed before either of them was dismissed. Neither Goddard nor Carlstein were run out at any point in the series, and indeed Carlstein wasn’t even playing in the second Test.

So it seems that in truth Barlow was not involved in a controversial dismissal in the first Test against England, although he certainly was in the third. At the time Barlow was on 41, on his way to 138. He went to play at a delivery from England off spinner Fred Titmus, missed, and the ball ballooned off his pad where it was safely caught by Peter Parfitt. Barlow and Titmus both say Parfitt was at slip, Wisden that he was at short leg. The most reliable witness is likely to be Fortune who described Parfitt as being at gully.

All are agreed there was a distinct noise and to a man England appealed, although if Fortune is being treated as the most reliable witness the point should be made that he describes a slight delay in the fielders going up. Barlow, whose account was that he had missed the ball completely but had hit his instep with his bat, stood his ground. The umpire’s finger stayed down and England were, to say the least, disgruntled, the normally phlegmatic Titmus being moved to call Barlow a cheating bastard to his face. The England fielders, bar skipper MJK Smith who did so half heartedly (according to Fortune) pointedly did not applaud Barlow’s century. If there were any doubt as to their intentions in not doing so those were dispelled soon afterwards when Barlow’s partner Tony Pithey got to fifty, at which point the England fielders congratulated him with gusto.

There was more to come next day when Kenny Barrington feathered a catch to the South African ‘keeper Denis Lindsay. Barrington always walked, but this time stayed put. Did Barrington’s reputation influence the umpire? Whether it did or not Barrington got the benefit of the doubt, but he couldn’t go through with that and then walked off. He hadn’t intended to embarrass the umpire in that way and did later give the official a sincere apology. Titmus also apologised to Barlow, under management orders. Barlow could tell that Titmus was not sorry at all and called him out on it. The bad blood simmered for a time, but not for too long.

England’s first Test victory led to some fairly pedestrian cricket as they adopted a safety first policy for the rest of the series. Despite his double failure in the first Test Barlow averaged more than 55, and showed great consistency, but neither he nor his side could quite get over the line. They had their revenge in England though, winning the second Test to take the series 1-0. Barlow was not at his best, contributing just a couple of fifties, but he did take part in one notorious episode. About an hour after their victory a number of the South Africans, Barlow included, walked back out to the pitch in their underpants and urinated on it. A photograph was taken that appeared in the newspapers in South Africa. Barlow admitted the stunt wasn’t classy, but apparently the story and accompanying image went down well in South Africa.

It was in the South African summer of 1966/67 that the great South African side of three years later began to take shape. Australia were beaten 3-1, and in fact those were the first three Test wins South Africa had achieved against Australia on home soil. Barlow was out of sorts with the bat, managing just a single half century, but he had a fine series with the ball, taking 15 wickets at 21.60. He again showed his ability to take wickets in clutches. In the first Test his contribution was crucial. South Africa were out for a disappointing 199 to which Australia replied strongly and took the lead with just one wicket down. At that point Goddard removed Lawry, and then Barlow opened the game up by getting rid of Ian Redpath, Bob Cowper and Keith Stackpole to leave the visitors on 218-5. A superb second innings performance then set up a handsome victory. The second Test was the one the hosts lost, but it did contain Barlow’s only Test five wicket haul, and the last three of them came whilst just five runs were added. By then however Australia were on their way to 542, and the damage had been done.

Three years later, the MCC visit of 1968/69 having been cancelled because of Basil D’Oliveira’s selection, South Africa played their last Test series for more than twenty years. Barlow dropped in to the middle order to accommodate Barry Richards and the Springboks heavily defeated Australia in each of the four Tests that were played. In the first and third Barlow scored centuries. In the fourth, restored to his familiar opening slot after Goddard was omitted, he contributed 73 to an opening partnership with Richards of 157, almost matching the young tyro stroke for stroke. He failed with the bat in the second Test but succeeded in wresting the ball from skipper Ali Bacher in both Australian innings. In the first he whipped out Ian Chappell, Bill Lawry and Doug Walters as Australia went from 44-1 to 48-4. In the second innings, rather than nag Bacher on the field Barlow decided to send him a telegram; ‘Please Doc, give me a bowl’. The result was the same – Bacher gave Barlow the ball and he responded by removing Eric Freeman, Brian Taber and Garth McKenzie as the visitors slid from 264-5 to 264-8.

In 1976 Barlow had his first taste of county cricket in England when he was signed by Derbyshire for a then eye-watering five figure salary. He struggled to start with in the unfamiliar conditions but found his feet in the second half of the summer. He replaced Bob Taylor as captain too late to rescue the side from another season of mediocrity, but he did make an immediate change to the fitness of his charges. In 1977 his own form fell away, particularly with the ball, but Wisden’s Derbyshire correspondent Mike Carey described his leadership as inspiring, and that an emphasis on attacking cricket was responsible for a marked improvement in the county’s results.

In Barlow’s third and final summer with Derbyshire it looked for a time as if the improvement would continue, the county riding high half way through the season. But the second half was a huge disappointment. Poor weather didn’t help, but even Barlow couldn’t make up for the loss of John Wright to the touring New Zealanders and the regular absence on England duty of Bob Taylor, Geoff Miller and Mike Hendrick. The side did get through to the final of the Benson and Hedges Cup, but it was not to be their year and the final against Kent was a one sided affair.

During his time at Derbyshire Barlow was one of those signed by Kerry Packer in 1977 for World Series Cricket. No longer quite the player he once was Barlow’s task in the main was to play with the WSC Cavaliers, a side that provided an opportunity for the fringe players and those returning from injury to take WSC out on the road outside the major centres. There was just one ‘Supertest’ for Barlow, the final one played on Australian soil. He reprised his role of almost a decade before, opening the batting against Australia with Richards. Barlow’s team won, comfortably enough in the end by five wickets, but on a personal level it was a disappointment for the 38 year old who was twice dismissed without scoring by Dennis Lillee and, if he even tried to do so, he did not catch the eye of his skipper Tony Greig whilst he was in the field.

It would not have been surprising if Barlow, pushing forty and with a business that did not run itself, left the game after his stint with World Series Cricket, but that was not the Barlow way. In fact he continued to play the First Class game for another five years, his last season being as late as 1982/83. Barlow captained Boland then, playing in the second tier of South African cricket.

Barlow was a liberal thinker and staunch opponent of apartheid. He was a member of the Progressive Federal Party throughout his adult life. During his playing career Barlow did not make too many public comments, but towards the end he agreed to stand in a by election. The small hard line South Africa Party had disbanded and its leader, John Wiley, had prompted the vote when he joined the ruling National Party. Barlow was 1,185 votes short of entering parliament. He did not stand again, somewhat disillusioned by the dog eat dog mentality of politics, but was left with one of his greatest memories, sharing a speaking platform with Helen Suzman, one of his heroes.

In the mid 1980s, in what some considered a volte face, Barlow opened a South African Sports Office in London. The organisation was funded jointly by the various South African sports bodies and federations and was wholly independent of the government. Barlow’s brief was to demonstrate the steps the various organisations had taken to open up the old racial divides and lobby for the return of sporting relations with South Africa. Barlow believed, on balance, that in the long run carrot rather than the stick was what was required to bring about fundamental change in South Africa, and that brought him into conflict with the hard line ‘no normal sport in an abnormal society’ brigade.

After three years in London and limited progress Barlow returned to South Africa and added his voice to the calls for major changes in the country. His phone was tapped, and he received numerous visits, often late at night, from the police, but he kept pushing his message across. No one partied harder than Barlow when, finally, the old order was pushed aside and the new South Africa was born.

In terms of how he earned his living Barlow’s early ventures outside the game were in farming. Initially he had a pig farm, and then a sheep farm before giving up on animals and growing grapes and making wine instead. All his projects had periods of success but ultimately seem to have suffered during Barlow’s somewhat up and down private life (he was married three times) and the need to periodically take his hand off the tiller due to cricketing and other commitments.

As well as his farming there was Barlow’s time in London followed, on his return to South Africa, by a stint as a financial advisor. In 1990 he was offered his first full time coaching role, with Gloucestershire. It was a tough assignment and Barlow did not stay too long. He was much more successful a couple of years later when he turned round the fortunes of Orange Free State before moving on to Transvaal.

The job in Transvaal ended somewhat unsatisfactorily after clashes with administrators and Barlow went back to his farm before being lured back into cricket by the offer to be the director of a cricket academy for Western Province/Boland in Paarl. This was one of Barlow’s real successes and he was particularly pleased to bring on Paul Adams, even if he was ultimately disappointed that the remarkable young bowler did not go on to dominate spin bowling in the way in which Barlow had at one stage hoped he might.

The academy job went as a consequence of the breakdown of Barlow’s second marriage but he was persuaded to take a break from farming once more by an offer to become the coach of Griqualand West. He made a good start, but after a year left after disagreements with his employers. He was not destined to coach in South Africa again and had expected to see out life on his farm until, in 1999, he received an offer to coach the Bangladesh national team. Uncertain as to whether to accept Barlow visited the country and fell under its spell. He made a significant contribution to the Tigers achieving Test status. He was present at the inaugural Test as well but, sadly, in a wheelchair having suffered a serious stroke at the end of April 2000.

After the stroke financial troubles hit Barlow and it was all he could do to clear his debts in South Africa by selling up. With his third wife he then relocated to Wales. The Professional Cricketer’s Association gave Barlow back his mobility in the form of an electric scooter, and he carried on coaching youngsters. A brain haemorrhage whilst he was spending Christmas on Jersey with his stepdaughter’s family for Christmas 2005 put him back in hospital. Sadly this time it was the end, and one of South Africa’s finest all-round cricketers was no more. There were many tributes paid, my personal favourite being from former Western Province wicketkeeper Andre Bruyns; In the great Test match in the sky, Eddie Barlow will win the toss and say ‘We’ll bowl – let’s see how good this Bradman guy really is’.

Leave a comment