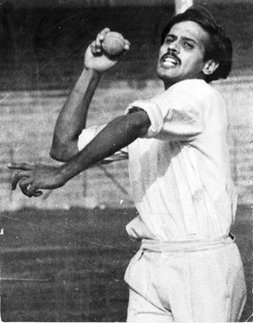

The Fourth Man – Venkat

Martin Chandler |

When India started to become a force in the international game, in the 1960s, it was her spin bowlers who were behind the rise and The Holy Trinity caught the imagination of the cricket world in a way that no combination of spinners had done for a decade and more, not since Sonny Ramadhin and Alf Valentine, and later in the early 1950s Jim Laker and Tony Lock.

History does not record who first dubbed Bedi, Pras and Chandra The Holy Trinity, but it is a soubriquet that has stood the test of time, even if it is slightly misleading, in that there were in fact four fine Indian spinners at the time. Srinivas Venkataraghavan was six months older than Bish, and made his Test debut before the great slow left armer, so all four men were very much contemporaries.

In the final analysis Venkat’s record is, statistically at least, somewhat inferior to the others, but 57 Test caps is confirmation of his importance to Indian cricket, and 156 wickets at 36.11 a presentable return. Whoever did give Bish, Chandra and Pras their famous soubriquet was probably not Indian, as home writers were and are more wont to speak of the Fabulous Four, and to elevate Venkat to the same status as his peers.

So it was most likely an Englishman who came up with Holy Trinity. The nation’s cricket lovers were held in thrall by Bish’s classical action, and by Pras’ loop and turn, which seemed to cast a spell over batsmen. Chandra was different, and unique – he had a brand of sorcery that nobody had seen before. The game in the 1960s was not too far away from becoming moribund, and these three spinners were a much needed injection of variety. And this is where Venkat lost out in English eyes; he bowled like an English off spinner of the time, quicker and flatter than Pras. He was accurate and difficult to score quickly from, but he seldom ran through sides, even in helpful conditions. We could see his type day in day out on the county circuit, the more so in the early 1970s as the desire to restrict scoring as much as take wickets, hastened by the spread of the one day game, made economy a watchword for bowlers of all types.

Venkat might be spoken of in the same breath more frequently had India played all four together more often. It only ever happened once, and given how the game unfolded when it did it surprises me it was never tried again. In 1967 India had a wretched time in England and lost the three match series 3-0. By the time that the final Test arrived what little pace bowling the tourists had was hors de combat so all four spinners played, and reserve keeper Budhi Kunderan in the first innings, and skipper Pataudi in the second, bowled a few overs of medium pace to take some of the shine from the ball. They shared the new ball with Venkatraman Subramanyan, normally a leg spinner but also bowling some military medium on this occasion.

England won easily again. India’s batting, with Sunil Gavaskar and Gundappa Viswanath still a couple of years away from breaking into the side, was simply too brittle and subsided for 92 and 277, but in dismissing England for 298 and 203 India bowled them out twice for the only time in the series, and the spinners took all but one of the wickets. There was just one victim for Venkat, but then he only bowled 18 overs, as against the 147 the Trinity were given. So perhaps that is the reason, that with three top class spinners there simply isn’t enough work for a fourth – the fact that Venkat was a class act, and very different from Pras, seems not to have mattered.

The impression is sometimes given that there was always a difficult choice to be made between the two off spinners, Pras and Venkat. In fact they played as many as 15 Tests together, all but one of them when Chandra was injured or out of favour. When the mercurial wrist spinner was fit and firing in the early years the decision boiled down to who was captain. Ajit Wadekar was a great admirer of Venkat the bowler and Venkat the man, writing of him in his autobiography On the surface there is a hard abrasive streak, but deep down he is very modest and understanding. He is forthright and given to plain speaking. He has no time for the sham and the superficial. His stiff and unbending attitude has been misunderstood. He is an introvert and a man of firm convictions. He is not willing to compromise any of his principles for the sake of convention.

Those traits to Venkat’s character did not, inevitably, endear him to everyone. He was notorious in Madras cricket circles for his fierce temper and was rarely a friend to young cricketers. Gulu Ezekiel, who saw him play top level club cricket into his 40s, remembers seeing him snap and snarl at a 17 year old Laxman Sivaramkrishnan during his first season of First Class cricket.. Gulu can still see the look of fear on Siva’s face as Venkat threw the ball at him after a misfield in a Ranji Trophy match in the early 1980s. There was a joke in the Madras cricketing community back then that the Chepauk outfield was as green as it was due to a fiercesome Venkat’s habit of spitting when angry – as he very often was.

Pataudi on the other hand greatly admired Pras, and Bedi and Chandra were Pataudi men as well. As for Venkat as late as 1969 Pataudi wrote in his autobiography that, as a bowler, he was not yet proven. Pataudi was clearly still not convinced by the time of the 1974/75 West Indies series when, after he regained the captaincy following Wadekar’s retirement, he was quick to drop Venkat and bring back Pras. As to the two spinners themselves their relationship seems to have been unaffected by the competition between them, Pras asserting in his 1977 autobiography that the the two had always been close friends. But then they did have a lot in common, aside from bowling off spin both were engineering graduates.

There was another distinction to be drawn with Venkat. Pras, Bedi and Chandra were not natural athletes, and offered little or nothing in the field or with the bat. Venkat’s batting stats are barely better than those of Pras and Bedi, but he was a more competent batsman than the others, and made a couple of important fifties in Tests. It is surprising , given his essentially sound technique, that his overall runs tally and average are as unimpressive as they appear on their face, a tendency to overuse the sweep shot being Wadekar’s verdict on the reason for that. Venkat was also a superb close catcher, particularly at slip, not a position where India had produced too many specialists before him.

Venkat was just 19 when he made his Test debut, in the home series against New Zealand in 1964/65. He made a steady start in the first three drawn Tests before recording what were to remain career best figures of 12-152 as India took the series in the fourth and final Test. Venkat thus began India’s next campaign, against West Indies at home two years later as the man in possession, but he failed to take the chance he was given in the first two Tests and Pras came back in the final Test and grasped his opportunity with both hands.

As Pras went from strength to strength Venkat must at times have wondered whether he would ever get his place back, but he worked hard in the nets, often bowling long spells at a single stump in order to enhance his control of flight, spin and length. In 1969/70 Chandra was, temporarily, a spent force and for the first Test against New Zealand at the Brabourne Stadium Pras and Bish were joined by three seamers. They still ended up doing most of the bowling, so Venkat was back for the second Test. He kept up his good record against the tourists with 11 wickets in the remaining two Tests of the series, and then played all five against Australia. He only took 12 wickets, but the cost was a modest 26.66.

After his success at home in 1969/70 it was inevitable that Venkat would be in the party that visited the Caribbean in 1970/71, although given his travails in England in 1967 his appointment as Ajit Wadekar’s vice-captain was not universally popular. As it was though he had the skipper’s backing, and that of his strong home association, and the doubters were comprehensively proved wrong. India won their first ever Test against West Indies, and went on to take the series, and Venkat played a major role. His 5-95 in the second innings at Port of Spain in the second Test paved the way for the solitary victory, and in the final Test his six wickets and innings of 51 and 21 played a big part in ensuring the draw that clinched the series. He played alongside Pras and, for the only time, comfortably out bowled him over a series in which they both featured.

In 1971 Chandra was back for the victorious trip to England, but it was Pras who missed out as Venkat, with 13 wickets, played his part in a series remembered primarily for Chandra’s matchwinning spell on the final day at the Oval. Venkat’s best return of the series was 4-52 in the second innings at Lord’s. Even though his Test career went on for another thirteen years he never did get another five wicket return after his effort in Port of Spain.

India’s next series was the return against England in 1972/73 and it was a case of deja vu for Venkat. Just like in 1966/67 his recent successes kept him in the side for the first Test, where he disappointed and gave way to Pras, and then failed again when given an opportunity in England in 1974. He didn’t let go however and had a bizarre experience against West Indies at home in 1974/75. Due to the selectors disciplining Bish he got back into the side for the first Test, and in a crushing defeat took six wickets, and outbowled Pras by a distance. With skipper Pataudi injured he was then appointed captain for the second Test. India lost by an innings and Venkat took just a single wicket and Pras four. With someone having to drop out to make way for Chandra’s return in the third Test Venkat went from skipper in one game to twelfth man and out of the series in the next.

In 1973 Venkat signed a three year contract to play for Derbyshire and thus like Bish gained first hand experience of the daily grind of county cricket. It seemed an odd choice for both. The county’s grounds had also been best suited to swing and seam bowling, and Derbyshire have had a succession of top class fast medium bowlers throughout their existence. Spinners on the other hand seldom thrived at Derby, Chesterfield and the outgrounds, and no spin bowler who was not also a capable batsman had, with one exception*, played any Test cricket. Venkat made a useful contribution to the county and, in the dry summer of 1975 enjoyed a particularly productive season with the ball. He no doubt also felt that he had a few points to prove after his second, slightly longer, stint as captain of India when he led them in their disappointing campaign in the first World Cup. Back in Derbyshire he contributed some useful runs in the lower order as well, without ever suggesting, as he sometimes did in domestic cricket in India, that he was capable of becoming a genuine all-rounder. Derbyshire chose not to renew Venkat’s contract for 1976, understandably given that they had managed to sigen South African Eddie Barlow in his stead, but it would have been interesting to see how well he would have fared in that long hot summer particularly in the August drought when almost all the pitches in the country became dustbowls, bereft of any grass.

There was some success for Venkat against his favoured opponents, the New Zealanders, in 1976/77, 11 wickets at 28 and his highest Test score of 64, but apart from that until the home series against West Indies in 1978/79 he seldom got a look in, and when he did achieved nothing of note.

Pras’ Test career had ended in a disappointing series defeat to Pakistan in 1978/79, the first time the countries had faced each other in the Test arena for 18 years. It was clear too that Bish and Chandra’s time at the top was drawing to a close, and the pair barely contributed to a hard fought victory against a West Indian side shorn of their WSC men. India’s bowling stars in their 1-0 victory were a pair of seamers, Karsan Ghavri and Kapil Dev, as well as Venkat, who rolled back the years with a return of 20 wickets at 24.75. Wisden described him as having played a vital role and India would hardly have won the fourth Test but for his contribution of four wickets in each innings, including the most important ones. He invariably struck when Ghavri and Kapil Dev had lost their edge and were being collared.

Venkat’s reward for his efforts against the West Indies was the captaincy for the third time, his brief covering the 1979 World Cup and the four Test series that followed. The World Cup experience was another chastening one. India lost by 9 wickets to West Indies, and by 8 wickets to New Zealand before crashing out of the tournament with a 47 run defeat at the hands of Sri Lanka, then still three years away from acquiring Test status. The Indians only took eight wickets in the entire tournament – none of them fell to their captain. In the Tests England won the first by an innings and but for the weather would surely have won the next two as well. As the final day of the fourth Test began India were 76-0 chasing a distant 438 for victory with defeat in the air once again. But they so nearly got there, and if they had the situation might have been different, but as it was Venkat, who had taken just six expensive wickets, lost the captaincy to Sunil Gavaskar. That decision was announced by the Commander of the Air India jumbo jet that was bringing the team home – Venkat deserved better.

Almost as soon as India got home they began a series against Australia. Venkat remained in the side for the first three Tests, but took just six expensive wickets. In the second Test a new off spinner, Shivlal Yadav had been blooded, and he was much more successful than Venkat so it appeared, after the veteran was dropped for the fourth Test, that the 33 year old had played his last for India. In fact he hadn’t though, as the selectors treatment of Yadav was not dissimilar to that of Venkat, and three years later the old man forced his way back into the side again. India had suffered a real mauling at the hands of Pakistan before leaving for the Caribbean and the selectors decided that experience and variety were needed, after they had played three left arm spinners, Dilip Doshi, Maninder Singh and Ravi Shashtri, against the Pakistanis. The West Indies tour was not a happy one for India. They lost two Tests to the World Champions, and of the other three one was ruined completely by the weather, which was all that saved them in the remaining two. Venkat’s 10 wickets cost him more than 50 runs apiece, but figures can be deceptive, and he bowled steadily throughout a difficult tour.

The end came four months later after Venkat was dropped again following the second Test of a return series against Pakistan. The 38 year old had taken just one wicket in the two drawn games, although in all probability the then skipper Kapil Dev did not know it would be the veteran’s final Test – had he done so then surely he would have given him the opportunity to take a parting shot in the meaningless Pakistan second innings of the second Test – as it was Venkat did not deliver even a single over as the nine bowled were shared around five Indians. Something else that Venkat has in common with Bish, Pras and Chandra is that his international career ended with a whimper rather than a bang.

It was almost a decade before a Test match ground saw Venkat again but, as an umpire, he was to officiate in 73 Test matches between 1993 and 2004, singlehandedly raising the reputation of Indian umpires from a low starting point. He was the first Indian Test player to become an umpire, and indeed there have only ever been a handful, and with the exception of Englishman Peter Willey still none who, like Venkat, have enjoyed long careers both as player and umpire. It is doubtful that Venkat’s feat of both captaining a side and umpiring in a Test at Lord’s will ever be matched.

Perhaps surprisingly in light of his temperament Venkat’s time as an umpire was marked by very little controversy. That was no doubt in part a result of his own insights into the stresses that players have to tolerate, coupled with the greater respect that the players, particularly bowlers would, not unnaturally, have for a man who had been in their shoes. He was a good umpire too of course, although his time in the middle was inevitably not free from mistakes, and he made one that may well have been of importance to the future of English cricket in just his second game. Mike Atherton and Alec Stewart found themselves at the same end of the pitch with one of them out, but who? Venkat’s decision, almost certainly incorrect, was to send Stewart on his way, and that decision might indirectly have influenced the appointment a few months later of Athers rather than Stewart as Graham Gooch’s successor as skipper.

In 2002 the ICC named its first elite panel of eight umpires. Venkat’s name was there, and so it remained until his retirement in January 2004. Early in his umpiring career he had also done some refereeing in Tests, and he reprised that particular skill in the first three IPL seasons. Again he seems to have avoided conflict and surely it must therefore be the case that the old firebrand who gave Sivaramakrishnan such a hard time has, as so many do, mellowed in his later years.

For me the Holy Trinity will always be a step above Venkat in the Pantheon of the game, but he was a fine bowler and whenever, as they always will be, the Trinity are mentioned when spin bowling comes up for discussion, Venkat’s name should not be overlooked.

*Tom Mitchell, a leg spinner who was a vital member of the Derbyshire side that won the County Championship for the, to date, only time in 1936. Mitchell played five Tests for England including the fourth match of the notorious “Bodyline” series of 1932/33, when his three victims included Australian skipper Bill Woodfull in both innings.

The QUARTET were in and out of the side.

Sad. None of them would have a streak like others.

Comment by Srinath | 7:26am BST 5 September 2023