The First Tied Test (Almost)

Martin Chandler |

It was not until the 498th Test match, in early December 1960 at the ‘Gabba in Brisbane, that international cricket saw its first tie. The penultimate delivery of the match brought a wonderful throw from Joe Solomon to run out Ian Meckiff and bring to an end a pulsating contest between West Indies and Australia that was the start of what became a classic series.

That match is still talked about today, and probably rather more so than the second tied Test, the 1052nd, that was played between India and Australia at Madras in September of 1986. One wonders how the two matches might be regarded today if they had in fact been the second and third tied Tests, and the first had been, as it should have, the second Test of the 1907/08 Ashes series at the Melbourne Cricket Ground. That one was Test cricket’s 97th encounter in the thirty one years since Australia, largely by dint of Charles Bannerman’s historic innings, had won the first ever Test at the same venue.

Back in 1907 Australia were led by Monty Noble, a fine all-rounder who was coming to the end of a distinguished career. He would lead his country again in England in 1909, but at 36 that would be the end. The home side’s opening batsmen were a pair of all time greats. Number one was the immortal Victor Trumper, still in his prime and as revered then as he is today. His partner was Charlie Macartney, although the match was only the Governor-General’s second. His great days were more than a decade away.

At first drop Australia had their first great left hander, Clem Hill. Although Hill was four years younger than Noble like his captain his best years were probably behind him, but he would remain a fine player for a while longer. He was followed by Noble and the Big Ship, Warwick Armstrong. The final two specialist batsmen were the veteran Percy McAlister and a young left hander, Vernon Ransford.

It was a top seven that in Noble, Armstrong and Macartney also contained three top class bowlers, and the attack was completed by tearaway pace bowler Tibby Cotter, left arm medium pacer Jack Saunders and a 19 year old off spinner, Gervys Hazlitt. The last man was wicketkeeper Hanson Carter, cricket’s best known undertaker.

As for England their side, and indeed the entire party, was some way short of being legitimately described as being representative of English cricket. Of those who had played in the 1905 home series only Wilfred Rhodes could be considered a first choice. The great Yorkshire slow left armer apart only skipper Arthur Jones and Colin Blythe from the 1907/08 party had featured in Stanley Jackson’s 1905 side, and they had played only twice and once respectively.

Had they been available any of the leading amateurs, CB Fry, Archie MacLaren, Stanley Jackson, Reggie Spooner, Gilbert Jessop and Tip Foster would have been preferred to Jones as captain, and the professional ranks too were depleted. Tom Hayward, Johnny Tyldesley, George Hirst and Dick Lilley all refused the terms offered by MCC. On the plus side the mercurial Sydney Barnes, who hadn’t been lured out of the leagues in 1905, had been persuaded to join the party, and a young uncapped Surrey batsman, Jack Hobbs, was also present.

For the second Test England’s opening batsmen were Hobbs, bizarrely left out of the first Test, and Frederick Fane of Essex. An amateur, and captain in Jones’ absence through illness, Fane never figured in a home Test, and although he visited South Africa twice the 1907/08 series was his only trip to Australia. That pair were followed by George Gunn, a superb batsman but, perhaps, his character militated him playing more Test cricket than he eventually did. The tour was Gunn’s first appearance in England colours. In fact he was not even selected in the original party and, having been sent to Australia by his county, Nottinghamshire, he joined the party on Jones falling ill. Gunn took the step up to Test cricket in his stride, and scored 119 and 74 in the first Test.

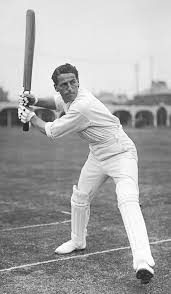

The England middle order were two more men new to Test cricket, Gunn’s county teammate Joe Hardstaff and Kent amateur Kenneth Hutchings (pictured). Following them were three all-rounders. Len Braund was a seasoned professional who had performed well in Australia in the past, and Rhodes needs no introduction. Amateur Jack Crawford played for Surrey and was a most interesting and prodigiously talented cricketer who, for a variety of reasons, never left the mark on the game that he should have.

The remaining three Englishmen were Barnes, the Derbyshire wicketkeeper Joe Humphries and Kent fast bowler Arthur Fielder. Humphries played his only Tests on the tour, and although Fielder had been a member of Pelham Warner’s side in 1903/04 he had made no impact in the one Test he was selected for. His other five caps all came in 1907/08.

What was not the most eagerly awaited series had an exciting beginning and the first Test might have been a tie as well the second. Set a fourth innings target of 274 for victory the Australians were never on top and when their eighth wicket fell at 219 it looked like England would, against expectations, go one up in the series. In the event however Cotter and Hazlitt saw Ausytalia home by two wickets.

The second Test began on New Year’s Day, and Noble won the toss and chose to bat. Very quickly Fielder got through Trumper’s defence and all but bowled him. He edged the next delivery to Gunn at third slip, but a none too difficult chance went down. The experience seemed to subdue Trumper who was not at his brilliant best.

At the close Australia were 255-7, a situation England would certainly not have been disappointed with. The only contemporary account of the tour, by Englishman Major Philip Trevor, described the wicket as perfect. Trumper eventually went for a, by his standards, watchful 49. All of the Australian batsmen got a start, but none went beyond the 61 that Noble contributed. Even so he might have gone earlier but the unfortunate Gunn, by then at mid on, put him down when he had scored just 19. Crawford was the pick of England’s bowlers and, remarkably, Barnes was the only one not to taste success, but his 17 overs for just 30 runs kept the pressure on the home batsmen.

Things got better for England next day as they took the last three Australian wickets whilst a mere 11 runs were added. They had cause to be grateful to Ransford, the last specialist batsman, whose self-inflicted run out was described by Trevor as foolish. With 5-79 Crawford took his first Test five-fer, something he was to repeat twice more before the series ended. Sadly despite being only 21 his Test career had, by then, run its course.

When England replied Hobbs, in his first Test innings, produced all the consummate skill that was to serve him and England well for the next 22 years. Fane and Gunn made 13 and 15 respectively and the most significant partnership of the innings occurred when Hobbs was joined at 61-2 by Hutchings. At 25, and just a few days older than Hobbs, Hutchings had been an immensely successful schoolboy at Tonbridge and had made a promising start for Kent in 1903.

In 1904 and 1905 Hutchings was barely seen on the First Class grounds of England, but in 1906 he came right to the forefront, averaging more than sixty for his county and being described by Wisden as the sensation of the season. He had not scored quite so heavily in 1907 but had still done enough to earn his invitation to tour. A right handed batsman with exceptionally strong wrists all contemporary writers comment on the power of Hutchings’ driving on either side of the wicket. Yorkshire’s Hirst, who generally fielded at mid off or mid on is said to have always retreated three or four yards in the field whenever Hutchings came to the crease. Perhaps more compelling evidence of his exceptional ability is that twice in a relatively short career Hutchings managed to break three bats in the course of an innings.

On 2nd January 1908 Hobbs and Hutchings put on 99 before Hobbs was dismissed for 83. Save for one difficult chance to square leg when he was 59 he had not put a foot wrong. He was replaced by Braund. With Hobbs at the other end Hutchings had batted with what Trevor described as unusual self-restraint and indeed Hobbs had outscored him. That all changed when Braund arrived however as in the final session of the day the pair put on 87, of which Braund contributed just 15. Hutchings passed his century and at the close England were very well placed just twenty runs in arrears with seven wickets standing.

A new day sadly brought a change for England. Hutchings added just nine to his overnight score, although he was not actually dismissed, for 126, until England had just got their noses in front. It was his only Test century and indeed he only managed one more half century, 59 against the 1909 Australians. Hutchings’ career never really kicked on from his wonderful summer of 1906. He did well enough in 1909 and 1910 but by 1912 he had retired from the First Class game in order to pursue business interests. Clearly a brave man Hutchings volunteered soon after the Great War began and, by then a Lieutenant, he was killed in action on the Somme in 1916.

There was no sudden collapse but, much like in the Australian innings, England’s remaining batsmen played themselves in and then got out, although it may have been different had an off drive from Crawford cleared the boundary at deep mid off rather than being superbly caught by Ransford. In the end England ended up with a lead of 116, distinctly useful but, on a wicket that was still excellent, disappointing given the start they had been given on the second day.

By the close of the third day England’s worst fears had been confirmed. The wicket was still playing well and their lead had been reduced to 20 and, Noble having gone in with Trumper himself, the experienced pair had been in no difficulty at all and scored their 96 runs at a run a minute.

On the fourth morning Australia continued on and took the lead with all their wickets still in hand before, once more, the complexion of the game quickly changed as they slumped from 126-0 to 135-3. Trumper was first to go as he was given out lbw trying to glance Crawford, and the same bowler then surprised Noble with a fast full toss that struck the batsman on the hand before falling on to his stumps. With Fielder promptly bursting through Hill’s defensive push Australia’s three best batsmen were back in the hutch with the side effectively 19-3. McAlister found himself run out not too long afterwards and suddenly everything for Australia, not for the last time, hinged on Armstrong and Macartney.

At this point the England’s bowling became, in Trevor’s words, somewhat commonplace without being really loose, and 106 were added before the next wicket fell at 268. At last Barnes had his first scalp when he bowled Armstrong. He later added Macartney and Ransford but well as he bowled he was unable to engineer the sort of collapse that England needed and Australia closed on 360-7, a useful if not yet match winning lead of 244.

The fifth day of the match, timeless as in those days all Tests in Australia were, was the most pedestrian of the match. It began with the Australians stretching their lead to 281, although that would have disappointed England after they dismissed Cotter with just a single added. Almost straight away after that Carter, on 22 overnight, gave a chance to Hutchings. Normally a safe pair of hands England’s first innings centurion failed to grasp the opportunity and Carter ended up being the last man out for a breezy 53.

When England began their pursuit of victory they were met by accurate bowling and keen fielding by the Australians and progress was slow. To begin with Hobbs and Fane put up 54 with the former batting every bit as well as he had in the first innings before being outdone by a superb delivery from Noble. Two balls later Noble removed Gunn for a duck to complete an unhappy match for the Notts batsman who had done so well in the first Test although, to show his strength of character, he was back in the runs in the next Test.

With Gunn’s dismissal Hutchings return to the wicket with the score on 54-2. These were dangerous times and the Hutchings on show was that of his first innings partnership with Hobbs rather than the one who had batted with Braund and he and Fane took England on to 121 before Fane was dismissed for exactly 50, his highest score of the series. Trevor described his innings as most valuable, faultless and meritorious. Hutchings lasted only a few overs after Fane’s dismissal but, Australian tails well up, Hardstaff and Braund made sure England would go into the sixth day without further loss. They were 159-4.

The final day dawned with England needing 123 runs and Australia six wickets. In Trevor’s words; All the morning hopes of an English victory grew fainter and fainter, and, as the wicket was practically as good as ever, it would be childish to attempt to make excuses for the failure of batsman after batsman of whom something was expected.

The problem started with just three runs added when Hardstaff was out thought by Cotter. The fast man bounced Hardstaff who hooked, fast and well. Unfortunately for him however he picked out the man on the fence and what might have been a six proved to be his downfall. Braund and Rhodes then added 34 but were out within two runs of each other before Crawford, after greeting the Australians with one blow for six attempted another and failed in his attempt to repeat the dose. After that Humphries and Barnes came together and in the short time left until lunch there were no further alarms. In the afternoon session England’s last two wickets were going to need to find another 66 runs.

Anyone with any knowledge of cricket history knows that Barnes could be a difficult and contrary individual. Acutely aware of the value of his skills he spent little time exhausting them in the six days a week world of county cricket, preferring the leagues and the occasional overseas tour. His bowling record is magnificent, and his batting average is that of a genuine tailender. On all accounts however Barnes was not a bad batsman at all and, had he ever put his mind to it, perfectly capable of becoming a genuine all-rounder.

In the days when wicketkeepers did not have to have any batting qualifications on their CVs Humphries was one of the more able with the willow, but even so his final average in First Class cricket was only 14.19, so Australian confidence was understandably high.

After lunch Barnes knuckled down and began to look like a batsman. It has been suggested that the motivation for the quality of his batting display in this match was his dissatisfaction with the standard of the umpiring he had seen in the match. Certainly he felt that he should not have waited so long for a wicket as he did, and history records that Gunn was less than impressed with the two lbw decisions that were made against him.

Humphries wisely decided to leave the batting to Barnes whenever possible, but wasn’t afraid to look for runs himself and he managed a couple of boundaries before, when the pair had added 43, Armstrong won an lbw appeal against the England ‘keeper. As with Gunn before him it was a decision the batsman did not relish, and whilst there was no open display of dissent Humphries was clearly reluctant to leave the crease.

The score was now 243, so still 39 needed, as Fielder came out to bat. At 11.31 Fielder’s career average was inferior to those of both Humphries and Barnes, but he is one of the very few men to have scored a century from number eleven, something he achieved for Kent against Worcester in 1909 in the course of a last wicket partnership of 235 with Frank Woolley.

Fielder batted as well as Humphries before him and Barnes continued apply himself to the task. There was nothing wrong with the bowling or fielding but, slowly but surely, their last pair inched England towards their target until the scores were level. Armstrong was bowling to Barnes and the fourth ball of the Big Ship’s over was played towards Hazlitt at point. Perhaps the tension had finally got to Barnes, but he set off for a run that palpably wasn’t there. All the teenager had to do was underarm the ball to Carter and Fielder would have been run out by yards, but he had a rush of blood to the head and flung the ball at the stumps with all the power he could muster. Sadly for him and Australia Hazlitt missed, Fielder got home and England had won by one wicket. Barnes was unbeaten on 38, which was to remain his highest Test innings.

In the first Test Hazlitt had played two fighting knocks without which his side could not have won, but he had not taken a wicket. In the second Test he had failed with the bat and, although he was not given many overs, again went wicketless. It was probably inevitable after his gaffe at the denouement that he would lose his place and he duly did. There was however to be a second coming for Hazlitt. Four years later with the series already lost he was called up for the final Test of the 1911/12 Ashes series. He took four wickets, and did enough to gain selection for the 1912 Triangular tournament where he was to record his best Test figures, 7-25 (including a spell of 5-1 in 17 deliveries) in a defeat against England at the Oval.

After the Triangular tournament it was to be more than eight years before Australia played Test cricket again, but by then Hazlitt was no more. He had always had a weak heart and, a schoolmaster outside the game, he contracted influenza in 1915. He carried on with life as best he could in circumstances where, in all probability, he should have taken to his bed. The illness developed into pneumonia and in the end the weak heart gave out and the popular 27 year old was no more.

As far as the 1907/08 series was concerned the excitement died down after the second Test. Australia recorded big wins in the third and fourth Tests and although England raised their game for the dead rubber they failed by 49 runs to take that and so the series was lost 4-1.

Leave a comment