The Cricket Web One Hit Wonders XI

Martin Chandler |

After my recent attempt at compiling a “dream team” from those who have never played Test cricket, my mind wandered onto those who have played Test cricket, but only once. It is remarkable just what a capricious lot selectors are. For all the talk that is often heard about giving players extended opportunities there are more than 350 of them who have only one cap. There are therefore plenty of candidates to choose from and my selection follows. The only qualification I have added to the obvious one is that a player’s career must be over, so I have not considered anyone still playing at senior level. With plenty of choice from all nations, I have come up with an eleven consisting of five Englishmen, two West Indians, two Australians, an Indian and a New Zealander. All my bowlers are English, but none of the batsmen, which might say something about England’s selectors or, most likely, says something about my selections. So I ask the same question as for the uncapped – how do you think my choice can be improved?

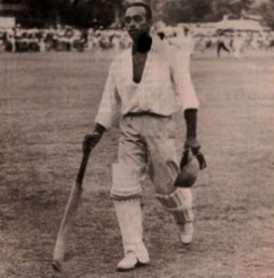

1. Andy Ganteaume West Indies

Sir Donald Bradman does not have the highest batting average of all who have played Test cricket. That honour belongs, technically, to the Trinidadian Andy Ganteaume who, in the second Test of the 1947/48 series against England, scored 112 in what was to prove his only Test innings. For that second Test injury problems forced West Indies into a situation where they had to pick a new and untried opening partnership of Ganteaume and George Carew. England won the toss and batted first and were all out for 362 after lunch on the second day. Carew and Ganteaume were not parted until early on the third morning when Carew, who had raced to 101 overnight, was LBW for 107. The mighty Everton Weekes came in at three and struck a rapid 36 before Frank Worrell joined Ganteaume in a partnership of 80, which ended when Ganteaume was caught at extra cover for 112. He had batted for four hours 30 minutes altogether and his innings, which contained 13 boundaries, was described by the Editor of Wisden, Norman Preston, as ?slow and boring?. History has tended to record that Ganteaume’s batting was selfish and that the innings, ultimately, cost his side victory. The truth is very different and I have examined it in detail in this feature. For present purposes it is sufficient to say that, while of course he wasn’t “Better than Bradman”, Andy Ganteaume was a batsman who should have had more opportunities than he did at Test level, and he is certainly the man I would want to take first knock in this team.

2. Rodney Redmond New Zealand

Ganteaume’s opening partner in this side has to be the one other man to have scored a century in his only Test. New Zealander Rodney Redmond was prevented from having a Test batting average higher than Sir Donald Bradman?s only because he also got to the crease in the second innings of his debut Test when he, following his first innings 107, went on to score another 56 to leave his average at a mere 81.50. Redmond, who was no doubt assisted by playing his Test on his home ground at Auckland, was a tall left handed opening batsman who was extremely strong off the front foot. He reached that debut century from just 110 deliveries in two hours and twelve minutes and hit twenty fours. When Majid Khan, admittedly not a regular bowler, was brought on to try and stem the tide he was treated with a degree of contempt by Redmond who struck each of his first five deliveries to the boundary. When Redmond was on 97 the anticipation amongst the spectators was such that as he despatched another delivery towards the mid wicket boundary approximately 300 people streamed onto the pitch to congratulate him. Amidst the ensuing chaos it was several minutes before the game could recommence and at that point, because of a magnificent stop on the boundary by Asif Iqbal, Redmond was still only on 99. Those amongst the Pakistani team who hoped that Redmond’s concentration might have been broken by the interruption were, however, to be disappointed, as he promptly proceeded to strike another four to bring up his century. The match itself petered out into a draw with, as indicated, just enough time for Redmond to enjoy himself again before his second innings dismissal. In the circumstances Redmond was an inevitable choice for the 1973 touring party to England where he must have confidently expected to add a further three Test caps. He started the tour well enough, scoring two half centuries against a strong D H Robins’ XI at Eastbourne, and he went on to record a further half century in his third innings of the tour against Worcestershire. That, however, was very much the high point of Redmond’s tour and he was not selected for any of the Test matches. There is no doubt that problems getting used to contact lenses hampered his play, however at least as important a factor is that Redmond was something of a “one trick pony” and it did not take very long for the hardnosed English professional bowlers to work out that he wanted to play exclusively on the front foot, so thereafter he was simply not given the sort of deliveries that he needed if his batting was to thrive. On his return to New Zealand Redmond did not play at all in the 1973/74 season, but did play domestic cricket in the following two seasons and in 1975/76 he recorded two centuries, including one in what was to prove to be his last First Class match. Redmond clearly decided that whatever he had achieved in 1975/76 was not going to be sufficient to regain his Test place and he left the game at the early age of 31. His son Aaron has, as at 2011, comfortably exceeded his father’s single cap by appearing in seven Test matches but, unlike his father, has not to date recorded a Test match century. Despite his shortcomings Rodney Redmond clearly had the temperament for Test cricket and, by weight of runs, he is entitled to his place in this team.

3. Ajay Sharma India

In January 1988 Ajay Sharma was a promising 23 year old . He had made his First Class debut three years previously. He had not pulled up too many trees but was averaging 40 and had clearly been marked out as one for the future. He received his call up for the final Test of that season’s home series against West Indies as a result of an injury to Dilip Vengsarkar, and while his was not a major contribution to a crushing Indian victory, his innings of 30 and 23 were useful nonetheless. By the time, ten months later, India played their next Test Vengsarkar was fit again and, understandably, was restored to the side – Sharma never found his way back. Over the next decade he scored prodigously in domestic cricket twice averaging over 100 for the season and three times over 90. It was not as if there was some sort of major disciplinary issue, as in the ensuing seasons he played in 31 ODIs, albeit with only modest success, but he clearly wasn’t “off the radar”. Sharma toured West Indies once, without success and without forcing his way into the Test side, and the feeling seems to have been that while he was utterly reliable on the docile home pitches that he couldn’t be trusted on wickets that had pace or bounce or offered the quicker bowlers movement off the seam or in the air. Given that only two batsmen in the history of the game have scored more than 10,000 runs at an average higher than Sharma’s 67.46, he was clearly extremely unlucky not to be selected again. There was a sad postscript to Sharma’s career when he was banned for life in 2001 for his involvement in the match fixing scandal that brought down Indian captain Mohammed Azharuddin. While, ultimately, his career ended in disgrace when I judge him as a cricketer alone I cannot leave Sharma out of this team.

4. Victor Stollmeyer West Indies

Vic Stollmeyer came from a prominent white family in Trinidad. In 1939, at the age of 23, together with younger brother Jeff, he came to England with that summer’s West Indian touring party. He was not an experienced player, he had played just six First Class matches prior to the tour, but he was a classy and fluent opening batsman who had averaged more than 58 despite being dismissed for 0 and 1 on debut. It had been intended that, as they did for Trinidad, Vic would open the innings with his 18 year old brother in the Tests but it was not to be. Vic struggled with illness throughout the tour and did not come into the side until the final Test when he came in at second drop. The tourists had not had a happy summer and although they restricted England to 352 in their first innings the expectation remained that they would do well to draw. In the event West Indies gave a glimpse of what was to come after the war as they scored 498. Vic scored 96 of those before he was stumped from the bowling of Gloucestershire off spinner Tom Goddard – he was playing defensively at the time and so it was just a lapse in concentration that took him out of his crease, in all probability thereby preventing Trinidad from having two batsmen whose Test average was higher than 99.94. Wisden described Stollmeyer in particular as showing “perfect style”, and the West Indies generally as being “a real joy to watch”. The tourist’s bowlers could not make the most of the first innings lead they were given and the match was drawn, bringing down the curtain on First Class cricket in England until 1946. There was still some First Class cricket played in the Caribbean during the war but, by the time Test cricket resumed for the West Indies in 1947/48, Vic Stollmeyer was concentrating on his legal career, and the First Class game had seen the last of him. This team needs a stylist so, while he might be an opener by inclination, I am picking Vic to bat in the position from which he produced that fine innings on Test debut.

5. Stuart Law Australia

If Stuart Law had been born 10 years earlier, or indeed ten years later, he would almost certainly have gone on to play many Tests for Australia. As it turned out for no reason other than the surfeit of gifted batsman that Australia had at the time, he played just once, in 1995 against Sri Lanka. It was not a taxing debut for Law, who came to the crease after a Michael Slater double century and a single one from Mark Waugh. Law’s involvement was to score an unbeaten 54 in a partnership of 121 with fellow debutant Ricky Ponting whose dismissal, for 96, brought about a declaration on 617-5. Steve Waugh was available again for the next Test and it was Law who made way for him – it is an interesting thought as to how differently their careers might have turned out had Ponting failed that day and Law kept his place . Australia’s innings victory even denied Law an average at the highest level, although his ODI career, which consisted of as many as 54 appearances, was rather more productive. My main memory of Stuart Law is his County Championship record for Essex against my beloved Lancashire – I see from the stats that he only averaged 85 against us – it seemed like a century ever time he got to the crease. Of course eventually he joined us, and while he wasn’t that prolific against all-comers, he was obviously a class above the rest of the Championship and when, late in his career, he became eligible for England, there were a few serious calls for his selection, and in my opinion he would certainly have performed better than some who were chosen. There is no contest for the number five slot in this team.

6. John King England

It has never been entirely clear whether the fact that the Leicestershire all-rounder John King played just one Test, the second against Australia in 1909, was because he was the victim or the beneficiary of one of the most controversial summers the England selectors ever had. The first Test was won easily by England by 10 wickets. For the second the selectors made as many as five changes to this winning team including introducing King. He batted at five and top scored with 60 in England’s disappointing first innings, and by all accounts batted very well. He then opened the bowling in the Australian second innings but ended up with just 1-99. His confidence clearly suffered early on when both Vernon Ransford, who went on to play the match winning innings, and Victor Trumper were put down off his bowling in the same over. In England’s second innings he failed, although he certainly wasn’t alone in that as the innings folded for just 121 and the Australians knocked off a small target for the loss of only one wicket. Further eccentric changes in personnell in the next three Tests saw England lose one and get the worse of draws in the other two to contrive to lose the series after that splendid start. So what of King? After top scoring in his first Test innings he was surely unlucky not to get another opportunity even if his original selection was one made on a whim. He had a very long career for Leicestershire, never a strong county, and his orthodox and effective batting brought him a career total of more than 25,000 runs at 27, with 34 centuries along the way. With the ball he bowled orthodox slow left arm and, utilising variations primarily of pace and flight, took more than 1,200 wickets at 25. Twice he accomplished the double. King did not retire until he was 54, and even in his last season in 1925, he was the man who scored the season’s first century. I firmly believe John King was a good enough cricketer to be given an extended run for England and he gets the all-rounder slot in this team.

7. Hammy Love+ Australia

There are, perhaps inevitably, quite a few wicketkeepers who have made a solitary Test appearance. The vagaries of the job, and the constant risk of injury, mean that short term deputies are needed more often than for any other discipline in the game. This team has a long tail so I need a ‘keeper with some batting credentials so Aussie Love is the man I choose. There was nothing at all remiss about Love’s glovework and it was one Test only because he had the misfortune to come to the fore at the same time as Bert Oldfield, and it was Oldfield’s famous injury, sustained when he ducked into that short pitched delivery from Harold Larwood in the third Test of the 1932/33 Bodyline series, that gave Love the chance to play in the fourth Test. There were three catches for Love amongst the 14 English wickets that fell, although he would have been disappointed to score just 8 runs in his two innings. That said in his entire First Class career Love averaged 35 with the bat, and was a heavy scorer in grade cricket, so he strikes me as the best choice for this side, just squeezing out his contemporary, Fred Price of Middlesex, who found Les Ames in the way of him ever getting more than one cap for England.

8. Charlie Parker* England

The Gloucestershire left arm spinner and occasional seamer, Charlie Parker, is by a distance the finest cricketer in this team. Only Wilfred Rhodes and “Tich” Freeman have taken more than Parker’s career total of 3,278 wickets, and he paid only 19 runs each for those. Parker was not a truly slow bowler, and variations in turn and pace, rather than flight, were his stock in trade, so he was more of a Verity than a Rhodes, but he was an attacking bowler even if it was sometimes said he did not react well to receiving being hit. Parker’s problem was his temper and his attitude to the amateurs that in his day controlled the destiny of the professionals. No secret was made by Parker of his egalitarian views and the powerful “Plum” Warner, who he famously once manhandled in a hotel lift, was someone who, to his cost, he particulary despised. The one Test cap that did come Parker’s way was in the fourth Test of the 1921 Ashes series when he was one of the changes rung by the selectors as they tried to halt the, by then, eight match losing streak against Australia. The dismal run duly ended, a draw being the result, and Parker, with 2-32 from 28 overs, bowled economically without the penetration needed to force a chance of victory. There were to be three further occasions, two in 1926 and one in 1930, when Parker was with an England squad only to be omitted on the morning of the match, in each case a controversial omission. Parker is a must pick for this side and with a long tail his batting is helpful. While certainly not being as a good a batsman as he thought he was, it is said he promised his Gloucestershire teammates every season that he would make 1,000 runs (in fact he only once got 500), he batted in orthodox fashion and, unlike most tailenders in his day, would never give his wicket away. With, hardly surprisingly in the circumstances, no obvious candidate for the captaincy I will, after much consideration, give the job to Parker. At Gloucestershire he played under Beverley Lyon, long recognised as one of the best and most imaginative captains the game has seen – Lyon was no respecter of authority either and as that encompassed a lack of interest in the distinction between professional and amateur, he and Parker were firm friends.

9. Joey Benjamin England

Joey Benjamin was already 27 when, in 1988, he played a solitary match for Warwickshire. He did enough in the latter part of the following year to play regularly, but after a reasonable season in 1990 he disappointed in 1991 and moved on to Surrey. Benjamin was strictly fast medium but he had a skiddy action and could bowl a decent out-swinger, and in 1994 he had an excellent season taking 80 wickets altogether at 20. His performances were such that when England went into the third and final Test against South Africa, on his home pitch, he was, to the surprise of many, preferred to Angus Fraser by the selectors. The panel were vindicated by an England victory that will always be remembered for Devon Malcolm’s electrifying 9-57 in the South African second innings, but it should not be forgotten that without Benjamin’s steady bowling in the first innings, when he took 4-42, including Hansie Cronje and Kepler Wessels when both were well set, Malcolm would not have had the chance to produce his career defining performance. There was never really any question but that Benjamin’s was a “hunch” pick, and it was no surprise that the selectors did not return to him in the future, but with a paucity of eligible opening bowlers the memory of that performance at the Oval persuades me that he is the man to open the bowling for this team.

10. Charles “Father” Marriott England

One of the best English wrist spinners to have played the game, Father Marriott bagged the remarkable match figures of 11-83 in his only Test, against West Indies in 1933. I would have loved to have seen Marriott bowl his action, by all accounts, being one of the oddest to have graced the game. Legend has it that he had a short, rather comical, prancing run in from the area of mid off before, immediately before his delivery stride, throwing his bowling arm behind his back with such force as to strike himself between the shoulders. The sound of the blow was, apparently, audible to the batsman – what Ricky Ponting might have thought of that is an interesting question. Marriott was a schoolmaster at Dulwich College and was therefore only available to play for Kent in the holidays and his committments outside the game were a contributory factor to his single appearance. In addition English cricket had, between the wars, plenty of other wrist spinners and Marriott was a distinctly ordinary batsman. As well as that while he seems to have had a safe enough pair of hands he was noted as a poor fielder at a time when fielding standards generally were not high. All things considered there is not a lot of competition for the wrist spinner’s berth in this team, and certainly a man with 11 wickets in his only Test, who paid just 20 runs apiece for his wickets over his career, gets my vote whatever his other shortcomings.

11. HD “Hopper” Read England

It is something of an indictment of Hopper Read’s batting ability that Marriott reaches the giddy heights of number 10 in this side. Both men achieved the true mark of the batting rabbit, in that they took more wickets over the course of their careers than they scored runs, but as I am aware of one occasion when Marriott batted for over half an hour against a class attack to save a game he gets the nod – but there is not much in it! Read flashed across English cricket like a comet in the sky. Effectively he played for just two seasons, 1934 and 1935. His reputation was as a tearaway fast bowler and there are a number of examples of his proving too hot for county batsmen to handle, but the one that catapulted him into the England side for his only Test cap began on 31 July 1935 against the mighty Yorkshire side that won the title that year. It was expected to be business as usual for the home side at Huddersfield. It was almost a year since they had last been defeated and lowly Essex were not expected to put up much opposition. In one of the most remarkable games in the history of the County Championship Yorkshire were bowled out for just 31 in their first innings, with Read taking 6-11 in six overs. He added three more in the second innings as Yorkshire, a little better at 99 all out this time, succumbed by the remarkable margin of an innings and 204. In 2011 terms it would be like Blackpool going to Old Trafford and beating Manchester United 6-0 in the Premiership. England were 1-0 down to South Africa and needed a win at the Oval and Read was included – sadly for England the pitch was a good one and the decision to put the visitors in proved to be the wrong one as they easily managed the draw they needed. Read took 6 for 200 in the match in fifty overs, so while there was no Test match glory for him he fully justified his selection. That winter Read toured Australia and New Zealand with what was, effectively, an England A side but, one match in 1948 apart, that tour was the end of his cricket career as he retired in order to concentrate on a career as a Chartered Accountant. For the genuine speed he will bring to this team Hopper Read just gets the nod in front of Derbyshire’s Arnold Warren.

Nice article Martin. 🙂

Where are the Baha Men, though?

Comment by SirBloody Idiot | 12:00am GMT 27 February 2011

Very interesting article, Martin. I suppose Rangy Nanan couldn’t displace Parker or Marriott. How about Arnold Warren? Got Trumper twice in his only match!

Comment by Dave Wilson | 12:00am GMT 1 March 2011