The Bank Clerk Who Went to War

Martin Chandler |

England set off to Australia this winter with considerable confidence. Recent Ashes history suggested that they did so with some justification, and not even Australia’s most fervent supporters, or those few English pundits who sounded just the odd word of caution, would have expected the series to turn out the way that it ultimately did.

What went wrong was, essentially, Mitchell Johnson. In England we all thought he was a spent force, and absolutely nothing to worry about. What has actually happened is that he inspired his teammates with bat and ball at the ‘Gabba, and on those rare occasions after that when he briefly relaxed, others stepped up to the plate and Australia did not just beat England, we were hammered. The depths that England have plumbed is illustrated by the fact that Bangladesh and Zimbabwe, the so-called minnows of Test cricket, would have expected to perform better this winter than the pampered stars of England did.

The first away Ashes series I followed closely was that of

1974/75. England were quietly confident then too. We had a team of good batsmen, and whilst Dennis Lillee had been a problem in 1972, similarly to Johnson this time round, he was believed to have been finished by injury. Bob Massie had lost his mojo completely so, the perceived wisdom said, there wasn’t much to fear. Of course when we got there it turned out that Lillee, like Johnson, had been reborn and to make matters worse some bloke called Thomson had appeared from nowhere.

That winter after five Tests it was 4-0 to Australia and the series was gone. The sixth and final Test served to underline just how significant frightening fast bowling was and is. Thomson was injured and Lillee broke down after just six overs. England’s battle weary batsman suddenly fired and led the side to a consolation innings victory.

Of the English batsmen only John Edrich, Alan Knott and Tony Greig managed to get to grips with Lillee and Thomson. Keith Fletcher and skipper Mike Denness scored big in the final Test, but without that their records would have been as poor of those of David Lloyd, Brian Luckhurst and Dennis Amiss. It is not dissimilar to what has happened to the English batsmen this winter save that only one English batsman, debutant Ben Stokes, has emerged with any credit, and by the time he got in the top order had already been blown away.

After England’s return in early 1975 their business for the new season began with the first World Cup, which was to be followed by a further series against Australia, this time of four Tests. The World Cup was a disappointment for England, who started as favourites, but went out to the Australians in a remarkable semi-final at Headingley. The Australians lost at Lord’s in the final to Clive Lloyd’s West Indies.

For most hardened England supporters the World Cup was just an experiment, enjoyable but of no great significance. The real examination of the summer was to be the series against Australia. The first Test was played at Edgbaston. The selectors resisted the temptation to make wholesale changes, so Denness remained as skipper, and Amiss and Fletcher kept their places. A young Graham Gooch was the only significant addition. Australia batted first and did not look particularly comfortable in totalling 359. But it was still enough to win by an innings with a day and a half to spare. Nothing had changed.

Tony Lewis summed up the importance of the latter part of the summer in a book about the 1975 season England is at war with Australia. Is there anyone who doubts it? We have tasted physical intimidation and verbal intimidation and after the innings defeat at Edgbaston we are struggling to rescue national pride. Denness fell on his sword immediately after the first Test, and his Test career ended. Fletcher too was dropped and while Amiss probably should have been a combination of innate caution and memories of his stirring deeds in the Caribbean in 1974 kept him in for one more match, albeit he was dropped down to four. Lancashire’s combative opener Barry Wood came in to open with Edrich. Bob Woolmer was, to general approval, given a debut. Another batsman was called up as well – Northamptonshire’s David Steele.

Steele was 33 and had made his First Class debut as long ago as 1963. It had taken him ten years, until 1972, for his average for a season to rise above 40. That year he had a fine summer, averaging 52, but the selectors did not come knocking on his door, and he assumed his chances of international honours were gone. In the summer of 1974 he had barely averaged 30. He was thought of as an honest county journeyman and his selection was a huge surprise.

It was a choice that was very much the brainchild of new captain Tony Greig, who wrote later It was a selection that was bound to be greeted with a mixture of curiosity and apprehension, maybe even a tinge of derision, but with an eye to selectorial collective responsibility Chairman Alec Bedser explained; The selectors were looking for a proven county batsman with the right methods, an ability to play fast bowling, guts and the character to take on Dennis Lillee and Jeff Thomson.

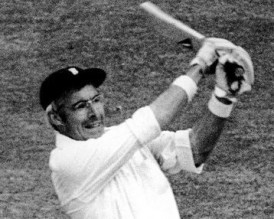

Greig won the toss and decided to bat. Steele, who had never before played in front of a big crowd let alone a full house for a Lord’s Test against Australia, had hoped that England might field first in order to give him a chance to get used to the atmosphere. As it was he had to pad up, and he was soon in action when Wood was plumb lbw to a delivery from Lillee that nipped back into him.

England’s new number three famously might have been timed out. Never having had to emerge from the home dressing room at Lord’s before he managed to go down one too many flights of stairs on his way to the long room, and ended up in the members’ toilets before having to turn back. When he finally got out to the middle he was greeted by the Australians with a snarled Who the hell is this? Groucho Marx?

Lillee was bowling at Steele and after a couple of routine defensive blocks he strayed a little towards leg and the debutant was able to turn the ball off his hips to the square leg boundary to get off the mark, bringing forth a huge roar from the crowd. He was not recognised as a quick scorer at county level, but then he rarely faced genuine pace, and even less frequently fields that comprised three slips, a couple of gullies, a short leg or two and no third man or fine leg. As soon as the ball left the square there were runs and Steele was not afraid to hook and pull.

As Steele became accustomed to his situation so the problems at the other end got bigger as Edrich, Amiss and Gooch all fell to Lillee to bring Greig to the wicket at 49-4. The captain flirted with joining his fallen colleagues to start with before settling down. In his own words I needed a fair amount of luck to see out his (Lillee’s) opening spell. Steele, however, seemed in little trouble. He even had the audacity to hook Lillee to the boundary on more than one occasion.

It was half way through the afternoon session that Greig and Steele were parted. They had put on 96 before Steele, having just gone to 50, momentarily lost concentration and played a Thomson delivery that he was trying to strike over the Tavern on to his stumps. Knott and to a lesser extent Woolmer carried on the good work and England totalled a respectable 315. They should have had a big first innings lead, but Lillee and Ross Edwards rescued Australia from 133-8 and the lead was only 47. A huge 175 from Edrich made sure England put themselves beyond defeat and changed the dynamics of the series. The veteran Surrey opener put on 104 with Steele, who added 45 to his first innings 50 before his concentration failed him again and he gave the man with the golden arm, Doug Walters, a return catch. It was nothing more than a loosener, all but a full toss, that was tamely struck straight back at the bowler.

Steele, who looked like anything but an international sportsman, had captured the public’s imagination. In his review of the match Lewis wrote In his long career with Northamptonshire he had grafted useful runs for many seasons, but without a hint of the class which one looks for the best players, before adding he proved on the very first morning in his very first Test that batting is about personality and character too.

John Woodcock, the Sage of Longparish, reported the match for The Cricketer. He praised Steele as well, and of course the selectors, whilst remarking on those fellow scribes of his who had reported on someone the selectors had dug up from Northamptonshire one day, and an inspired selection the next.

The third Test at Headingley might have given England a victory. The final day dawned with Australia on 220-3 chasing 445 to win. One of the most exciting ever climaxes to a Test match looked possible, but when the teams arrived it became clear that supporters of a convicted armed robber, George Davis, had vandalised the pitch in order to publicise their campaign for his release. It was a huge disappointment, although given the rain that lashed down in Leeds that day barring a miraculous Australian collapse between the showers there would have been no definite result anyway. A year later Davis was released due to concerns about the identification evidence that convicted him. Two years on from that and he was back in prison for armed robbery, this time following a guilty plea.

With innings of 73 and 92 Steele top scored in both England innings at Headingley. In Woodcock’s words it was A case of fortune favouring the resolute, and certainly one or two hooks from Lillee and Thomson might, on a different day, have had different outcomes. Lewis summed up the public mood; Around David Steele there has built up a sort of John Bull hero cult – the silver-haired lad of quiet demeanour, spectacles, jockey cap and a stout heart, called to do special duty for his country. He strides to the wicket with the gait of a man with trouble to sort out – like a vicar turned gunfighter.

The final Test at the Oval threatened for a time to be an Australian rout. After Chappelli won the toss he led from the front with 192 before declaring at 532-9. Lillee, Thomson and Max Walker then dismissed England for 191. For Steele it was his lowest innings yet, 39, but he top scored again. He contributed 66 to England’s rearguard action in the follow on as well, although for once there was a more telling contribution, Woolmer’s painstaking 149 compiled over more than eight hours.

England had still lost the series courtesy of their defeat at Edgbaston. But after three well earned draws dignity had been regained, and a new folk hero had arrived. The name of David Steele does not resonate down through the years like some but in 1975 he became a national treasure. Before him only Jim Laker from the world of cricket, courtesy of his famous 19/90 in 1956, had won the BBC Television Sports Personality of the Year award. Since 1975 there have been just two more, Ian Botham in 1981 and Andrew Flintoff in 2005, so Steele is in exalted company. He also won numerous lesser awards and, having had the good fortune to coincide his annus mirabilis with his benefit season, he was GBP25,500 better off, a very substantial sum in those days.

Not quite everyone bought into all the hype. England had no tour in 1975/76, their next trip overseas being scheduled for 1976/77 to India. There was already speculation about Steele being Greig’s vice-captain for the trip, but there was a warning in The Cricketer from veteran writer Alex Bannister;Some see him as a one season wonder whose technical weaknesses will be exposed on faster pitches and facing classier spin bowlers. He is clumsy against spin bowling, and every county pace bowler will say he hooks high and tends to give catches at long leg.

In the long hot summer of 1976 Greig promised to make the West Indies grovel. The early incarnation of the four pronged pace attack was not yet strong enough to inflict a 5-0 defeat, but 3-0 was pretty comprehensive. In the first Test Viv Richards made 232 as Lloyd’s men built up an impregnable lead, but England drew the game comfortably enough. Steele entered the fray in the first innings with England yet to open their account after Mike Brearley’s early dismissal, but he was still there at the close of play, having carried on where he left off against Australia and finally reached his first Test century. Unfortunately for England he was dismissed early on the fourth day, one of those mis-timed hooks going to hand. He had done enough though, and despite his first failure for England in the second innings Greig’s men were not in any danger of defeat.

The second Test was drawn too, Greig even being able to exert a bit of pressure at the end albeit England were never in with a real chance of victory. They had bowled well in the visitors first innings and, unusually, got a first innings lead without a significant contribution from Steele, but they needed his top score of 64 in the second innings in order to stay far enough ahead to avoid defeat.

The third Test saw the floodgates open after the notorious assault on John Edrich and Brian Close at the start of England’s reply to a West Indian total of 211, an innings that had been rescued almost singlehandedly by Gordon Greenidge after his side had slipped to 26-4. England were all out for 71 and 126 and lost by 425 runs in the end. No English batsman scored more runs in the match than Steele’s 35, but his harum scarum 20 in the first knock, followed by being out hooking for the fourth time in the series in the second, meant that the patience of some who mattered was beginning to wear just a little thin.

For the fourth Test Close and Edrich were dropped, so England had no openers. The job fell to Steele and Woolmer. Never an opener Steele told David Tossell in 2007 That was a shit decision, it really was. Thanks to Greig and Alan Knott England got to within 55 of winning. For Steele the game was a depressing one. He was yorked by Michael Holding in the first innings for just four and Andy Roberts produced a beauty for his second delivery second time round and he was caught behind for what turned out to be his only Test duck.

For the final Test Steele was restored to his favoured number three slot and Amiss came back to partner Woolmer at the top of the order. Amiss’ return was to be a personal triumph amid the third successive defeat. First of all however the Oval crowd were treated to what was to remain Vivian Richards’ highest Test score, 291, as West Indies got to 687 before Lloyd declared with 8 down. Amiss then scored 203, but England still lost by 231 runs. For Steele there was something of a return to form with innings of 44 and 42, but it was not enough to get him on the trip to India.

There was a huge wave of public sympathy for Steele following his omission and he himself wrote

I thought I had done as much as anyone over the two series in which I played, and made as many runs as just about any other batsman. I had not played as well against the West Indies as I did in the Australian series, but I still made runs. And so I thought I was in with a good chance to tour. It was not to be. The selectors took some stick in the press, and a lot more in pubs and pavilions up and down the land but, to prove they did know a thing or two, the team they picked became the first since Douglas Jardine’s, more than forty years previously, to win in India.

David Steele’s Test career ended at the Oval in 1976. He had only played eight Tests, but made a bigger impact than players with many more caps. If his omission from the squad for India was a disappointment he did at least have the consolation of helping Northamptonshire win their first ever trophy, the 1976 Gillette Cup, when firm favourites Lancashire were beaten, comfortably enough in the end, but with a few wobbles along the way. Steele continued with the county for a couple more seasons before, at the end of the 1978 summer, leaving the club he had first appeared for back in 1963. Steele, by then 37, was offered the captaincy of nearby Derbyshire after the return to South Africa of Eddie Barlow. He had a fine season with bat and ball, the slow left arm orthodox that he had mothballed during his early thirties proving better than ever. But he found that leadership did not come naturally to him, and he chose to drop back into the ranks half way through the season.

Steele served Derbyshire well for three summers. His batting was not quite what it once was, but his bowling more than made up for that and in his final season with the county he led their bowling averages. He left Derby “by mutual consent” after 1981 but, despite being 40 was still not finished, and he returned to Northamptonshire. He had three more seasons of First Class cricket. He slipped down to the lower middle order, and did not score a single century in his second spell with the county, but he still scored useful runs. With the ball he had the three most productive summers of his career, so he was still a vital component of the team Geoff Cook led.

A printer by trade Steele went back into that industry after his career in county cricket ended. It wasn’t always plain sailing, and in 1989 a company he co-owned was forced into liquidation, but he was still able to retire a few years ago. He spent some of his time coaching, most notably at Oakham School, where he helped to bring on the only man other than Stokes to have emerged with any real credit from the train wreck that was the 2013/14 Ashes series, Stuart Broad. Nowadays Steele supplements his income by after dinner speaking, and is the first former cricketer I recall seeing with a line ad in The Cricketer advertising his services in that field. Perhaps the man who used to be nicknamed “Crime” (as in ‘crime doesn’t pay’) simply doesn’t fancy sharing his income with an agent. In any event I am told by those who have seen him in action that he is an excellent raconteur, and not prohibitively expensive.

So perhaps what a new set of England selectors should do in the 2014 season is have a look around the counties for an unheralded batsman who has learnt his craft the hard way, and who has the maturity that will ensure he can do a job to help hold our batting together in 2015.

I am more than happy to leave a comment here about this article. Great composition but more than that it brings the good memories back of a true English hero. What more can I say?

Comment by paul mullarkey | 12:00am GMT 18 January 2014

Deposited a few into the stands iirc.

Comment by benchmark00 | 12:00am GMT 18 January 2014

Another great piece, fred.

Sad to say, I think your wish expressed in the last paragraph for a similar county championship honed unheralded hero is likely to be a forlorn one, but it’s perhaps interesting to note that the overall FC average of Jos Buttler is very similar to Mr Steele’s. One hopes the selectorial personages might show similar gumption to Greig and take a similar punt on talent, character and the evidence of their eyes rather than being slaves to stats.

Comment by BoyBrumby | 12:00am GMT 22 January 2014

Alex Gidman, imo

Comment by fredfertang | 12:00am GMT 22 January 2014

That David Steele was ‘clumsy’ against spin bowling has been the reason given by most commentators as to why he didn’t get selected for the 1975 tour of India. But that doesn’t explain why he wasn’t selected for the 1977 Tests against Australia when he done so well against the Windies the previous summer. After all, Dennis Amiss was picked yet again after failing on every single previous Ashes series, and that didn’t stop the selectors being overly generous and picking a ‘has been’.

No, I reckon that that there must have been something ‘personal’ going on. A ‘personal vendetta’ against Steele of some kind?

Comment by watson | 12:00am GMT 23 January 2014

I think he was off the radar by then, and Mike Brearley and Derek Randall were ahead of him

Comment by fredfertang | 12:00am GMT 23 January 2014

[QUOTE=fredfertang;3220249]I think he was off the radar by then, and Mike Brearley and Derek Randall were ahead of him[/QUOTE]

That’s right, Randall’s brilliant innings in the one-off Centenary Test handed him his Ashes spot, and Brearley was overdue for a decent stint as captain. Boycott then returned from exile for the third Test in 1977. However, even at the time I was miffed that Steele had given way to Amiss who predictably had two horrible opening Tests at Lords and Manchester before being dropped. Steele would have done a lot better against Thomo and Pascoe who demolished Amiss’ and his short lived experiment of taking an off stump guard and standing chest-on just like Peter Willey.

Comment by watson | 12:00am GMT 24 January 2014

I agree with you, but Amiss was fireproof at the start of the series – he’d come back with that double ton against the WIndies and done well over the winter including a fifty in the centenary Test so he was always going to get a chance

In many ways though I’m glad that Steele never got back in – if he’d run out of luck, as had to be on the cards it would have spoiled a terrific story in the same way it would if Andy Ganteaume had ever played another Test

Comment by fredfertang | 12:00am GMT 24 January 2014

[QUOTE=fredfertang;3220655]I agree with you, but Amiss was fireproof at the start of the series – he’d come back with that double ton against the WIndies and done well over the winter including a fifty in the centenary Test so he was always going to get a chance

In many ways though I’m glad that Steele never got back in – if he’d run out of luck, as had to be on the cards it would have spoiled a terrific story in the same way it would if Andy Ganteaume had ever played another Test[/QUOTE]

I’m not sure that luck has much to do with it. After all, a batsman doesn’t average 40 something against Lillee, Holding, and Roberts unless he has a sound technique. He would have gone alright for 30 or more Tests I reckon.

But yes, such a brief career does make for a good story.

Comment by watson | 12:00am GMT 24 January 2014

I’m not sure that Amiss and Brearley kept Steele out of the side, as they were opening and Steele batted at 3. Boycs replaced Amiss when he made himself available didn’t he?

You couldn’t argue about Randall’s selection after Melbourne, or even Woolmer’s since he made hundreds at the start of the series. But Steele could legitmately feel aggrieved at losing out to guys like Barlow and Roope in that series.

He could also feel aggrieved about missing the India tour as most of the guys who did go barely made a run, so he could hardly have done much worse than them. Amiss and Greig excepted, of course.

Comment by wpdavid | 12:00am GMT 24 January 2014

He did have a basically sound technique, albeit one that involved playing off his front foot whenever possible, but there’s no doubt that if you were willing him to succeed, as the whole nation did, that your heart was in your mouth every time he pulled/hooked – he didn’t roll his wrists like someone like Vishy did, and he certainly kept the bowlers and the leg side fielders interested

Comment by fredfertang | 12:00am GMT 24 January 2014

I think we can safely conclude that Steele was a one-off selection coup.

Perhaps his demise from the team was something to do with the fact that he was essentially a Tony Greig project.

Comment by GuyFromLancs | 12:00am GMT 28 January 2014

Steele was the sort of guy who thrived when the score was 20 for 2 rather than 200 for 2. Loved his nickname they gave him at the bar. “Crime”- doesn’t pay. LMAO!!

Comment by paulted | 12:00am GMT 28 February 2014