That Bloody Little Pain in the Arse

Martin Chandler |

Few men manage to remain universally popular throughout whatever career path they choose. For professional sportsmen, given the intense rivalries that come with the territory, it is all but impossible to do so. There are some whose standards of play and sportsmanship ensure they always command the greatest of respect, by which I am referring to the likes of Bobby Charlton, Colin Cowdrey and Roger Federer, but that is not quite the same thing. The man I have in mind as one who did achieve such a level of admiration is Derek Randall, who celebrated his sixtieth birthday earlier this year, and who has always been one of my favourite cricketers.

There are many reasons for Randall’s popularity a major one, of course, being his skill as a batsman. Unorthodox and always ready to improvise in order to keep the scoreboard moving Randall demanded attention, and while he was at the crease spectators seldom moved from their seats. Ultimately career statistics do not lie, and Randall’s demonstrate that his batting was just short of the highest class, but in addition to his one masterpiece, that 174 in the Centenary Test, he played a number of other fine innings and often lifted English spirits in times of adversity. By way of example no one who saw it will forget his determined second innings century against Pakistan at Edgbaston in 1982 when, as makeshift opener, he made 105 out of the 188 England had scored by the time he was the eighth man out. Only two other men from the top eight managed double figures, Tavare and Gower, with 17 and 13 respectively. There would have been no England win without Randall’s effort. A different type of Randall innings was an exuberant 83 against New Zealand scored in company with Botham. Even Richard Hadlee was, as happened on very few occasions against England, made to look human as the pair put on 186 in just 32 overs.

His shortcomings as a batsman conceded there is no need to do the same for Randall’s qualities as a fielder. He was quite simply magnificent. He was by no means the game’s first great fielder but no one, not even Clive Lloyd, had lurked in the covers in quite the same way before. Randall was one of the first to bring to his efforts in the field the spectacular dives and willingness to throw himself at the ball that we now take for granted.

Randall was also a selfless individual, a quality guaranteed to enhance any man’s reputation. A cursory glance at his career record clearly demonstrates that his best position in the batting order was five or six – perhaps it is something about fielding in the covers as like Lloyd he was never a confident starter – despite this over his 47 Test career at some time or other Randall occupied each of the first seven positions in the England order. This willingness to do whatever was asked of him for his country doubtless played a part in his Test career ending at the comparatively early age of 33. In the winter of 1983/84 Randall had performed well, if a little inconsistently, in Pakistan and New Zealand. The following summer was to be the first of the two 5-0 “blackwashes” that England suffered at the hands of the West Indies in the 1980s. For the first Test Randall was selected to bat at three – he didn’t mind – as long as he was playing for England he would be happy to bat anywhere. As expected he found himself at the crease early in both innings and made just a single. He was by no means the only failure amongst the England batting but it was he who was dropped – he was never invited to play for his country again.

Another, better remembered, example of Randall putting the interests of others ahead of his own came in the fourth Test of the 1977 Ashes series. Randall was playing his eighth Test, and significantly his first before his adoring home crowd at Trent Bridge. The biggest news in this match was however the return to the England colours of Geoffrey Boycott, once again available for selection after ending his self-imposed exile. When England batted they started well enough in pursuit of a modest Australian total of 243 before two wickets fell at 34. This brought Randall to the crease to join Boycott and a tumultuous reception greeted the local hero. There were a couple of boundaries as Randall settled in while Boycott remained largely becalmed. Suddenly, following a gentle defensive push, Boycott set off for a run that even a man as fleet of foot as Randall had no chance of completing. It was Boycott’s call and a dreadful one. There was no reason at all for Randall to sacrifice himself, but true to his nature he did. History records that all was eventually well as Boycott, clearly distraught as Randall trudged off, went on to make a match-winning century.

Another major factor in Randall’s popularity was his eccentric personality. Some, including many in an excellent position to judge, declared he was bonkers. Opponents usually only sledged him once. He constantly talked to himself while batting anyway and if anyone wanted to chat to him he wasn’t fussy about who they were or what they said – he was just delighted to engage them in conversation. As his career progressed it became recognised that if you wanted to disturb Randall the better approach was actually not to talk to him at all.

Spectators loved Derek Randall. On his first England tour, to India in 1976/77, his repertoire of handstands and cartwheels whilst on the field enthralled the crowd. His incessant banter appealed to them as well. In an early tour match, while twelfth man, he left the pavilion to wander round the ground. He signed some autographs, shook a few hands, pulled some funny faces and chatted to the locals. Eventually he decided to adjust a police officer’s helmet, while the officer was wearing it of course, at which point the game stopped and Randall was unceremoniously ordered by his teammates to return to the pavilion – a stage had been reached where no one was watching the cricket – the entire crowd were only interested in what Randall was doing.

The above said his teammates also enjoyed his humour. A famous tale surrounds an incident that occurred on the 1982/83 tour of Australia. Inevitably there are a few accounts of this episode, all slightly different, but the common thread is that a number of England players were in a bar in Adelaide in what amounted to the city’s red light district. There is a lack of consensus as to how the conversation developed but the result was that Ian Botham bet Randall ten dollars that if he went outside in drag and purported to tout for business he would not get picked up. I have seen no satisfactory explanation as to just how a young woman in the bar was persuaded to exchange clothes with Randall but suffice it to say a few minutes later he left the bar dressed in a tight leather skirt and waving a handbag. A few seconds of exaggerated hip swinging and lip pouting later a car pulled over and to the general astonishment of the rest of the team Randall got inside and the car drove off. By the time he reappeared, looking somewhat dishevelled, even Botham was beginning to show some concern at the lapse of time. As Randall pocketed Botham’s ten dollars he explained that his “punter” had, on being told, refused to believe he was a member of the England cricket team and had proceeded to try and embrace him whereupon Randall had had to strike him several times with his handbag in order to make good his escape!

Returning to the subject of his cricket Randall was 21 when he made his debut for Notts in 1972 against Essex at Newark. On an outground, against an attack that included the fine West Indian paceman Keith Boyce, and three quality spin bowlers in Robin Hobbs, Ray East and David Acfield, a highly aggressive 78, including five 6s, meant that he grabbed the limelight from the off. His electrifying fielding made sure that no one took their eye off him and by the time his batting started to show some consistency in 1975 it was always going to be just a matter of time before he was called up for England. That call finally came the following summer when he was twelfth man for two of the Tests against West Indies in the series made famous by the backlash that arose from Tony Greig’s “grovel” comment.

With the Test series ending in an embarassing defeat the selectors picked some young blood for the three match ODI series that followed. The pattern of the Tests was repeated and the visitors won 3-0 but Randall took the opportunity to cement his place on that winter’s tour to India by top scoring with 88 on debut in the second match, and following that up with 39 at a strike rate of 134 in the third match as England chased an impossible 224 in just 32 overs.

In India Randall came into the side for the second Test and received much praise for the manner in which he scored 37 on debut. Sadly however after that innings he failed to improve on it in six attempts and ended up averaging just 12. He was by no means certain of a place in the starting line-up for the Centenary Test. Landmark matches have come and gone with some regularity in recent years and it is therefore worth stressing just how big an event this was. It was exactly 100 years since the first ever Test match had been played at the Melbourne Cricket Ground and no expense had been spared in celebrating. Every famous old player who was fit and willing to travel had been flown in and the Queen was due on the final day. Australia had destroyed England two winters previously, and had done the same to the West Indians a year later. Given the drubbing that those same West Indians had then handed out to England just a few months previously it was hardly surprising that the Australians were not expecting to be tested. With the Royal Visit due on the fifth day there were well-founded fears that the match would not go the distance and an ODI had been pencilled in for day five – what, asked the bullish Australian press, were the players then expected to do on the scheduled fourth day?

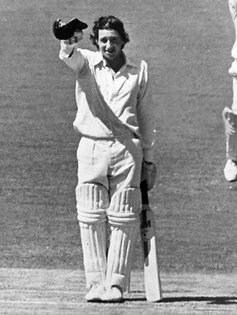

Tony Greig won the toss and decided to field. He thought there was some moisture in the pitch, although he was also keen not to see his batsmen exposed to Denis Lillee too soon. As things turned out it was an inspired decision and only Greg Chappell showed any sort of assurance as Australia were bundled out before the close for just 138. England lost Bob Woolmer in getting to 29 that evening. Illustrating perfectly his characteristic ability to say the wrong thing, Greig declared If I live to be 95 I shall never forget this day. Next day England were duly all out for exactly 95. Randall came and went, scratching around for just four before he had to take sudden evasive action to a Lillee bumper. Instantly he adopted the pose you see in the accompanying image, doffing his cap to the great fast bowler. Lillee was not impressed, and according to Randall the next two deliveries were a yard quicker. He nicked the second one and became the first of Rod Marsh’s four victims in the innings, and the second of Lillee’s six.

Australia had a wobble again in their second innings but half centuries from Ian Davis, David Hookes and Doug Walters, together with a fine unbeaten century from Rod Marsh enabled Chappell to declare on 419-9, thus setting England the small matter of 463 to win in 590 minutes plus 15 eight-ball overs. Randall was at number three on this occasion and was padded up from the off. Woolmer was out on the stroke of lunch with England on 28 so Randall had a forty minute wait before starting his innings. He ate nothing during that interval – he sat by himself in a corner of the dressing room giving himself a pep talk – his teammates knew better than to disturb him.

Skipper Greig took him to one side just before he and Mike Brearley went out to resume the innings. Greig stressed to him the importance of not losing his concentration, and he had plenty to reflect on as he walked out to begin his innings on the biggest playing area in the world It was deafening, 70,000 bloomin’ Aussies, baying for blood he later recalled.

Randall is not a tall man, no more than 5 feet 9 inches, but he has size 11 feet which gave him a gait faintly reminiscent of Donald Duck. His mannerisms endeared him to the Australian crowd as they did to crowds the world over, but for the Aussie team there was inevitably an element of a red rag to a bull about the way he twirled his bat and played imaginary cover drives as he wandered towards the crease to face Max Walker. Left armer Gary Gilmour was, at this stage, operating from the other end. Randall generally liked to play a couple of shots in order to get underway but for once he heeded the entreaties of his captain to be careful, echoed repeatedly by partner Brearley. Slowly but surely he got underway and Chappell had to bring Lillee back. He began with a vicious bouncer that whistled past Randall’s face followed by a short ball that had him hanging out his bat outside off stump. Livid with himself Randall admonished himself severely as he waited for Lillee’s third delivery. This time it was Lillee’s turn to curse as Randall drove the ball back past him. It was the only occasion in his epic innings on which Randall recalls scoring any runs from Lillee from a straight hit.

Lillee was not used to losing the psychological battle with batsmen but this time he did. Randall took to delivering his own verdicts if Lillee appealed, and would gesture polite acknowledgements at the bowler when beaten. Lillee was furious, and as this byplay unfolded the crowd, who did not doubt for one moment that Australia would run out as winners, began, as crowds always did, to warm to Randall and get behind him rather than the great fast bowler. This can only have served to further frustrate Lillee.

Brearley and Randall safely negotiated the afternoon session and just before the interval Randall went to his 50 – on 42 he might just have been out, a full blooded cut shot from a Lillee delivery flying from the middle of the bat through Kerry O’Keeffe’s hands at gully, but it would have been a remarkable catch.

Brearley was removed by Lillee straight after tea which brought Amiss in to join Randall. Amiss had been one of those most shell shocked after the 1974/75 series and it was a result of that that he was now batting in the middle order rather than going in first, which was how he had made his name. The batsmen made a point of rotating the strike against Lillee and both survived until an early closure, brought about by bad light, with England on 191-2, still 272 short of victory, but with their batting pride restored thanks in large part to Randall who was on 87.

Randall sensibly kept away from the ongoing centenary celebrations that night and went to bed early although he was unable to sleep, spending the night reliving the shots he had played during the day. He was at the ground first thing next morning and took a long net, taking with him a young Botham and Yorkshire’s Graham Stevenson, both of whom were on scholarships in Australia, with the request that they did all they could to replicate Lillee’s signature delivery, the one that bites, lifts and moves away from the right hander.

The preparation worked and Randall moved easily on to 95 at which point Lillee began what was to prove a memorable over. The second delivery, short and pitched outside off stump was cut past second slip for four – A bit risky, that shot Randall subsequently conceded, although by now both bowler and pitch had lost a little of their early pace. On 99 Randall now realised he was one away from his century and got lucky. Lillee dredged up his full pace once more and also brought the ball into Randall who was delighted to take the resultant single when the thunderbolt clipped his glove and was deflected towards fine leg. Amiss then took a single and when Randall got back into the firing line there were three deliveries to go. For the first Lillee really slipped himself and the short delivery got some extra bounce and struck Randall just above the left temple. Understandably knocked off his feet Randall made sure he maintained his mental hold on the bowler by quickly getting up and saying If you’d hit me anywhere else you might have hurt me. Still dazed Randall played and missed at the last two deliveries, both of which passed just over the stumps.

Amiss managed to take a couple of overs of Lillee to enable Randall to clear his head but it was not long before Lillee had another chance to bowl at him. This time Randall saw the late bounce and ducked and swayed backwards with such a jerk that he again lost balance. This time however, rather than end up in a heap, he executed a textbook backward roll before springing straight back up and looking the astonished bowler in the eye. Again the crowd roared its approval, and Lillee rolled his eyes, looked skyward and wondered just what he had to do to dislodge the man he later described, with a rueful smile, as that bloody little pain in the arse.

At lunch Randall was 129 and England were 196 runs away from a remarkable win. Lesser men than Greig might have decided to shut up shop but instead he asked his batsmen to accelerate and the dutiful Randall did so. In the third over after the interval he hit 4-2-4 from successive deliveries from Lillee. At the other end Amiss did not, unfortunately for England, last much longer and Fletcher quickly followed before Randall was joined by his captain. They progressed well until at 320 an often forgotten incident occurred. Randall was on 161 at the time, and being tied down by Greg Chappell, bowling defensively. In an attempt to force the pace Randall missed the ball which went between bat and pad but there was a noise. Marsh swooped, tumbled and came up with the ball in his right hand. Chappell’s strident appeal was answered in the affirmative by the square leg umpire and a disconsolate Randall began to walk off until Marsh called him back, making it clear that irrespective of whether Randall had got a touch he had not taken the ball cleanly. Marsh was one of the toughest competitors the game has seen but, clearly, an honourable man. Randall was by now, understandably, exhausted and it was a lapse in concentration that saw the end of his innings 13 runs later when he was adjudged to have been caught off bat and pad by Gary Cosier at short leg from a Kerry O’Keeffe googly. Randall was not convinced he had got a touch but despite his huge disappointment at the decision he, remembering Marsh’s gesture, immediately walked off without question.

His epic innings finally over the entertainment Randall provided was still not quite at an end. About twenty yards from the pavilion gate there was a similar opening that led into the crowd and up to the executive box where, at this point, the Queen and Prince Philip were installed. Randall made the wrong choice and ended up about ten yards from the royal couple before he realised his mistake. He bowed, turned round and walked across a row of seats and over to the pavilion where some members of the security staff helped him in.

The rest of the England order followed Randall’s example and Greig and Alan Knott in particular batted well before Australia eventually overcame them to win by just 45 runs, coincidentally of course the precise margin by which their predecessors had won the first ever Test match, one hundred years previously.

Lillee had taken 11 wickets in the match and was bowling as well at the end as he had at the beginning but, despite his efforts ultimately being in vain, it was generally accepted that the man of the match award had rightly gone to Randall. The Englishman was shrewd enough to make sure he obtained all of his teammates signatures to the bat he had wielded to such remarkable effect, and then, thoughtfully and selflessly he gave away that wonderful piece of memorabilia. Remarkably the donee was one of the wealthiest men in the world, J Paul Getty, a great friend of English cricket and a man who had always been supportive of Randall. How else do you repay a multi-billionaire? is the simple response that any enquiry as to his motivation in making the gift is met with.

Following his remarkable innings Randall was the talk of English cricket although he never did quite live up to lofty expectations he had created. A big innings against a Packer ravaged Australia in 1978/79 apart it was to be more than five years before he scored another Test century, and while he managed another four in the next two years that solitary appearance against the West Indies in 1984 was his last. His Test career over Randall continued to play for Notts until he was 42 and in 1991, his 41st year, he had an Indian summer as he enjoyed the best season of his career with over 1,500 runs, five centuries, and an average of more than 62. After a disappointing 1993 season Randall left the Notts staff but he continued to play Minor Counties cricket, for Suffolk, until he was 50 and after that he played club cricket for Matlock and I understand he turned out occasionally for the club as late as 2010.

His First Class career over Randall moved into coaching. He is currently the professional at Bedford School, a post he has held for a number of years, and where he has guided the development of many young cricketers. His greatest success has been the role he played in the formative years of Essex and England batsman Alistair Cook. Randall himself might have been one of the more unorthodox players the game has seen, but he played his part in moulding the exemplary technique of the young Cook who has said of him Derek Randall’s enthusiasm was phenomenal …… one of his great attributes was that he would put just as much effort into any session, whether it was with the first team or the prep school.. For those of us who remember Randall in his pomp those comments come as no surprise. His love for the game from which he derived his living was patently obvious in everything he did. His enthusiasm was infectious, and his supporters faith in him never faltered, irrespective of the diappointments that were part and parcel of being a member of the Derek Randall fan club.

Appalling technique, terrible footwork and couldn’t read the spinners to save his granny. His Test record is obviously very modest but it’s better than I would have predicted when he was first selected.

Comment by Lillian Thomson | 12:00am BST 29 July 2011

Cracking article, most enjoyable.

Comment by keeper | 12:00am BST 29 July 2011

What a fantastic piece and brings back so many great memories of Derek. I was brought up in the same town as him and played cricket at the same club. I even lived just three doors away from his future wife and I particularly remember him going round the estate knocking on the kids doors and he took a big group of us to the swimming baths one Sunday morning. Spontaneous. A legend, whos final analysis might not be at the top but I doubt that many cricketers could ever match him for the joy he brought to peope.

Comment by Alan | 12:00am BST 29 July 2011

Brilliant in the field, top sledger apparently, saw his innings in the centenary test and would rate in the top ten i have seen

Comment by JBMAC | 12:00am BST 29 July 2011

Well written, interesting article on a great character –

Comment by Graaarm | 12:00am BST 29 July 2011

As a teenager living in Australia but having been born in England, I had a massive crush on Derek! He was the subject of my scrapbooks, my girly gossip aand my 16 year old heart! Just loved his quirkiness, cheeky smile and Brillant fielding. Still love you Derek!

Comment by Jacqueline Reid | 12:00am BST 13 July 2013

Great article about a great man. The world would be a better place with a few more people like Derek Randall wandering around in it, just oozing infectious enthusiasm for life itself.

Comment by Stuart | 12:00am BST 31 July 2013