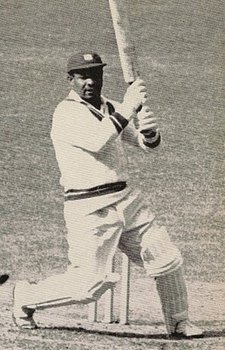

Sir Everton Weekes

Martin Chandler |

Unlike his fellow Ws, Frank Worrell and Clyde Walcott, Everton Weekes came from a difficult background in Barbados. He, together with his sister, was brought up by his mother and an aunt in a small home just a stone’s throw from Kensington Oval. In the best attempt he could make to support his family Weekes’ father emigrated to Trinidad where he worked in the oilfields in order to earn sufficient funds to send home and enable his family to eke out a living.

Despite his family’s poverty Weekes was entitled to an education, largely based on an English curriculum with a heavy religious bias, and that took up his time until he was 14. At that age he left school but, shunning the menial work that most in his position were forced to seek out, he did little other than play cricket until, at 17, he joined the British Army. Having rejected labouring, and not having the qualifications to join the Civil Service immediately, the military was Weekes’ only real option and he stayed there for five years. Having had a strict upbringing from his mother and aunt the discipline of Army life did not trouble him, and the opportunities to play cricket and football were an important factor in his development as a batsman.

Domestic cricket in Barbados in those days fell into two distict camps, the Barbados Cricket Association (BCA) and the Barbados Cricket League (BCL). The BCA was where the selectors looked for those who were picked for the full Barbados side. It consisted of the premier clubs on the island as well as the higher schools and colleges and it was via that route that Walcott and Worrell came to the selectors’ attention.

The BCL was very much the poor relation and its top players had to find some way into a BCA team if they harboured any ambition to play the game at First Class level. Another result of Weekes’ Army service was that a route into the BCA opened up for him. He scored heavily for the Garrison side in the BCA and an invitation to play for Barbados arrived in 1945 when he played twice against Trinidad. His debut was not a success, but at least he was in good company, his 0 and 8 mirroring the scores that Walcott had made on his First Class bow three years previously. The fact that Weekes was almost 20 on debut, as opposed to Walcott’s 16 and Worrell’s 17, shows how he was held back by his background.

In his second match Weekes was switched to the unfamiliar role of opening batsman, but he got his first half century and held his place albeit he did not make any real impact as an opener. It was not until the beginning of the 1946/47 season, and a move to his favoured favoured slot at number four, that the runs really began to flow, and his first century, against British Guiana, came in his sixth First Class match. He never looked back.

In 1947/48 England were in the Caribbean. West Indies had not played Test cricket since 1939 so there was no natural order of things and, the tour beginning in Barbados, Weekes had an early chance to show his abilities and he took full advantage, scoring a century in the first of two matches between the tourists and the colony. Weekes played in all four Tests. In the first three he could not get beyond 36, although by the same token he did not score less than 20. The great George Headley was due to be recalled as captain for the final Test in his home island of Jamaica, and to take Weekes’ place. Sadly for the locals he was injured so Weekes stayed on and his 141, in the face of an unexpectedly hostile reception from the Jamaican crowd, who had wanted to see their own JK Holt take Headley’s place, was the matchwinning contribution. West Indies took the series 2-0.

Next up for Weekes was a remarkable trip to India, one which, had he been held in the slips by England before he got off the mark in that final Test, he might not have even made the boat for. There were five Tests and a 1-0 series win for the visitors. Weekes got to the wicket seven times. In the first three Tests he scored a century in each of his four innings before missing out on a fifth by just ten runs when he was run out. In the second innings of the fifth Test, another two runs and he would have gone through the series without failing to achieve at least a half century on each of his visits to the crease. He averaged 111.

News did not travel as fast in the late 1940s as it does today but news of Weekes’ exploits got to England with sufficient speed to alert the clubs in the northern leagues to this great new talent. It was Lancashire League Bacup who secured Weekes’ signature for the 1949 summer and, save for three years when touring commitments prevented him from doing so, he played for them as a hugely popular and successful professional for a decade. There was, in the early days, an approach from Kent. In those days in order to gain the necessary residential qualification Weekes would have had to have foregone his Test career. It seems unlikely he was ever seriously tempted, but any interest quickly evaporated once he discovered that as Bacup’s professional, playing just at weekends with some coaching to do in the week, he already earned rather more than the iconic Denis Compton picked up at Middlesex.

It is hardly surprising in the circumstances that Weekes reached 1,000 Test runs faster than anyone, even Bradman, and it seems improbable that that 12 innings record is likely to be beaten any time soon. As to what sort of batsman Weekes was he was something of a contrast to the willowy figure of Worrell and the big powerful frame of Walcott. He was short in stature, and often compared to Headley both in skill and technique. To go to much further with that is an unrealistic comparison as, unlike his illustrious predecessor, Weekes operated within a strong batting line-up, but given the reverence with which Headley is treated it puts Weekes abilities in context. Denis Compton wrote of him long after they had both retired that he …flashed across the international cricket firmament with the brilliance of a meteorite. Seldom failing to attack and exhibiting all manner of exotic strokes and improvisations he was vastly entertaining, whilst Compton’s England teammate Jim Laker, who saw plenty of Weekes whilst bowling at him, wrote ruefully he has the killer instinct. He murders bowling that is in the slightest degree untidy …. with a gift of timing the ball that is bestowed only on the very best. Laker, perhaps the greatest off spinner to have played the game, faced Weekes 13 times in Tests. He dismissed him once in their first meeting, and once in their last, but never in between.

His feats in India meant that Weekes arrived in England in 1950 with a big reputation to live up to. By the beginning of July he had succeeded way beyond anyone’s expectations as he had already recorded four double centuries and a triple, and he ended the tour with an average of almost 80. He was not quite as prolific in the four Tests as his side took the series 3-1, but a century and three fifties gave him an average of 56.

In the Southern Hemisphere summer of 1951/52 Australia hosted West Indies, for the first time in more than twenty years, for what was dubbed by the press as the game’s World Championship. Weekes was as ineffective as most of the visiting batsmen, although in his case there were compelling mitigating circumstances. In the first Test, a low scoring encounter won by Australia by three wickets, Weekes scored 35 and what should have been a matchwinning 70 in the second. There were however a number of disastrous mistakes in the field that allowed Australia to scrape home. Worse than that was the fact that in that Australian run chase Weekes pulled a leg muscle so badly that he really should have taken a long rest. Unfortunately the tour management decided that he could not be spared, and he had to play on despite only being able to do so with the help of daily injections. Even so he was never properly mobile in any of the remaining four Tests and inevitably suffered, finishing the series with an average of just 24.

The following winter brought India to the Caribbean for the first time and a contest that was all about which of the competing spin attacks of Alf Valentine and Sonny Ramadhin for the home side, and Fergie Gupte and Vinoo Mankad for the visitors, was best able to deal with the conditions. Gupte just shaded Valentine, but couldn’t prevent Weekes maintaining his three figure average against India by scoring 716 runs at 102. With Walcott also scoring heavily the West Indians simply outgunned their opponents, and took the series by winning the only Test to reach a definite conclusion.

The Caribbean’s visitors the following year were Len Hutton’s England. The series was an ill-tempered one, with England promising in Brian Statham and a young Freddie Trueman, an even more potent pace attack than the Australian one that had humbled the West Indies two years previously. Again Weekes wasn’t fully fit, and again it was problems with a leg muscle, but this time he was not so severely restricted and although he was unable to play in the second Test he still managed almost 500 runs at an average only a fraction away from 70. He was disappointed that he could not help his team hang on to the 2-0 lead that they built up in the first two Tests, but at least they held England and retained, albeit for just another twelve months, their proud record of never having lost a series at home.

In 1955 West Indies were comprehensively beaten by Australia by 3-0 to finally end their unbeaten run. It was nothing to do with Walcott, who scored 827 runs at 82, or Weekes, who averaged 58, but the home side’s bowling was lamentably weak. There were no pace bowlers of note in the Caribbean in those days, and the threat of Ramadhin and Valentine was largely diffused by the Australians’ development of the pad play that Colin Cowdrey and Peter May were to perfect two years later. The once lethal pair took just five wickets each, paying 76 and 69 runs respectively, and both were dropped before the end of the tour. West Indies leading bowler was all rounder Denis Atkinson whose medium pace brought him 13 wickets at 35 runs each. The next most prolific wicket taker was a young Gary Sobers, with 6. It didn’t matter how many runs Walcott and Weekes scored when there was no possibility of their teammates taking twenty wickets.

Eight months after the disappointment against Australia Weekes had an enjoyable tour of New Zealand where, as the senior batsman amongst a young and experimental line-up, he scored three centuries in the Tests and averaged 83. The New Zealanders were not a strong bowling side, but they were at home and, for once, like his hero Headley, Weekes was very much the strong link in an otherwise inexperienced and untested batting order.

Weekes penultimate series was the saddest of them all, the 3-0 drubbing by England in 1957. At least in Australia in 1951/52 West Indies could learn from their mistakes in the field but, as soon as Cowdrey and May showed that, given prevailing umpiring attitudes, Ramadhin and Valentine could just be padded away, any prospect of West Indian success evaporated in the face of one of the most powerful England sides ever put together. For Weekes there were just 195 runs and an average of 19, but on a personal level it was 1951/52 all over again. His leg problems over the years left Weekes with a legacy of reflexes that were not quite what he would have liked, although such was his class that he largely dealt with that problem. The real problem in 1957 was sinusitis and five times during the tour he had to undergo a surgical procedure to unblock his troublesome sinuses. The relevant symptoms were headaches and, on occasion, blurred vision – hardly an ideal starting point for facing an attack as strong as Trueman, Statham, Trevor Bailey, Laker and Tony Lock.

There were other problems to in 1957. John Goddard, who had led the triumphant march through England in 1950, was invited out of retirement to lead West Indies. He wasn’t worth his place and the failure to appoint Worrell irritated Weekes, as did the attitude of the management who thought that he and Walcott were rather less incapacitated than they actually were, a problem that blew up in the Board’s face when, following the team’s return to the Caribbean, those accusations were made public. Weekes 90 at Lord’s was forgotten. It did not prevent West Indies losing heavily, but Compton was moved to write of the innings In every respect it was the innings of a genius.. Former Jamaican Prime Minister and author of an authoritative book on the history of West Indian cricket, Michael Manley, wrote that the innings would be remembered …with awe for all that it fell short of the classic milestone.

Four months after the touring party returned to the Caribbean West Indies were hosting Pakistan for the then newest member of Test cricket’s family’s first visit there. Weekes scored his fifteenth and last Test century in the First Test and went on to average 65 over the series, but despite being just 33 he retired from Test cricket at the end of the series. He still felt aggrieved at the comments made at the end of the 1957 tour, and indeed a number of powerful figures in the Caribbean, including Forbes Burnham the Premier of British Guiana, tried to persuade him to take legal action against the board. Exactly what happened I do not know, and I doubt that Weekes was keen on litigation, but ultimately the Board issued an appropriate statement regarding Weekes and his contribution to West Indies cricket, and there the matter was allowed to rest.

Although Weekes had called time on his international career he continued to play at First Class level for Barbados, as well as various invitational XIs, until 1964. His record over that time strongly suggests that the timing of his leaving the Test arena was propitious, although he did pass his hundred once more, in his penultimate game, against Jamaica. He had, since 1958, been a coach in Barbados and a very fine one he turned out to be, influencing many of the top Barbadian players down the years. In 1979 he took the Canadian national team to the World Cup in England, although he was unable to mould the part time players at his disposal into a competitive side.

There was also a place in the commentary box for Everton Weekes, a task which he carried out very well both on radio and television. Briefly he was an ICC Match Referee and, rather more regularly, he represented his country at contract bridge, a sure sign that, his humble beginnings notwithstanding, Weekes was a highly intelligent man. In 1995 he became Sir Everton Weekes. It was thirty years previously that that honour had been bestowed on Frank Worrell, but just a twelve month after Clyde Walcott. Worrell of course departed this mortal coil just three years after he became a knight. Walcott had a decade in which to enjoy the status he richly deserved before he passed away in 2006. Everton Weekes however I am delighted to report is still with us, still living in Barbados, in his 88th year.

Lovely stuff. Really enjoyed the entire series. Has made for excellent reading.

Comment by Eds | 12:00am BST 29 September 2012

Great piece, and a great tribute to a great man. As a batsman not quite in the Headley, Sobers, Richards and Lara, But with the tremainder of the 3W’s and Kanhai takes a place just a hair below and all true ATG’s in the truest meaning of the term.

I enjoyed the series, and thanks to all concerned.

Comment by kyear2 | 12:00am BST 29 September 2012

It wasn’t mentioned but Weekes was also a superb ATG slip who was rated by those who saw him as the equal to Hammond, particularily to spin.

Comment by kyear2 | 12:00am BST 29 September 2012