Sid Barnes – The Turnstile Hurdler and Other Stories ……

Martin Chandler |

Sid Barnes’ father did not live to see his younger son born, let alone witness any of his achievements on the cricket field, and doubtless that contributed to the man that he became. Sid was therefore brought up by his mother, clearly a formidable lady who must have been a huge influence on his personality. If losing her husband were not enough, shortly after Sid’s birth in 1916 Jane Barnes was diagnosed with breast cancer and made what must have been the extraordinarily difficult decision, given the state of medical science at the time, to have a double mastectomy. That it was the right decision cannot be doubted – she lived another 60 years.

The lady was also a shrewd businesswoman. After her husband’s death she moved the family into the city of Sydney and used the proceeds of his estate to purchase a number of properties, the family income being the rents from those, and the profits from a taxi business that was built up over the years. The son clearly, like his English namesake from an earlier time, knew his own worth, and acquired an entrepreneurial flair from his mother.

Thus Barnes was not keen on playing cricket as an amateur, and his Test career suffered as a result. He was happy to come to England, where commercial opportunities aplenty were to be found, but he rejected the £450 on offer to tour South Africa in 1949/50 as insufficient, and even when England toured Australia in 1950/51 he chose to accept a lucrative contract to spend the series in the press box rather than make himself available for selection. On a smaller scale, but perhaps a better way of illustrating the point, is an incident in 1948 when a UK tobacco company paid each of the Invincibles five pounds to appear in a brochure. Only Barnes was missing, the company baulking at the fifty pounds he demanded.

It should be stressed though that Barnes was not motivated solely by the acquisition of money for himself. He raised substantial amounts for charitable causes by, with the assistance of Bill O’Reilly, showing films that he had taken during his career. On a more personal level after the war he sent food parcels to friends in London, and when New South Wales teammate Bill Alley suffered three bereavements in rapid succession a couple of years later Barnes helped him with the funeral and other expenses.

Barnes also had a sense of humour, albeit an unpredictable one, and as a couple of tales illustrate he was also wont to take things too far on occasion. In England in 1948, when the Invincibles played Leicestershire umpire Alec Skelding would not give them anything. Barnes chuntered away at the umpire who, himself something of a comedian, wrote Barnes a note later explaining he had left his guide dog outside the ground. When the two met again at the Oval later on the tour a small terrier that ran on to the outfield gave Barnes an opportunity he could not resist. He picked the animal up and ran over to Skelding with it. Apparently Barnes did not know that Skelding was terrified of dogs, and much amusement resulted from the sight of an umpire in a First Class match running hard for the pavilion being chased by a fielder with a small dog in his arms.

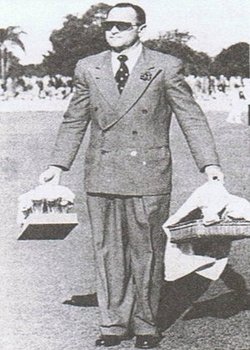

The second incident was, effectively, the last act of Barnes’ Sheffield Shield career and came in a game for New South Wales against South Australia in November 1952 in which Barnes did not even play. He had been hoping to get back in the Test side and, having made runs against the touring South Africans immediately followed by a big hundred against Victoria, he thought he had done enough, as indeed did everyone else bar the selectors. Once he was left out, and knowing his chance was gone, Barnes asked to be twelfth man for the South Australia game and, having gained permission from the umpires, his final on-field joke came during a drinks interval. Barnes emerged in a lounge suit and sunglasses carrying a basket of drinks in one hand and a radio in the other. He offered cigars to the players, a quick style make-over to Keith Miller, and a spray of scent to any fielder who wanted one. The crowd enjoyed the joke initially, but Barnes theatrics went on too long and the spectators began to jeer him. Any residual goodwill towards him vanished when, his concentration obviously broken Dean Trowse, a promising young South Australian batsman, was dismissed immediately after the eight minute interval.

To return to his cricket Barnes is one of the great “What ifs” of the game. Many cricketers lost their best years to the Second World War, and many amateurs found the call of business too loud to ignore, but add to those factors the controversies that deprived Barnes of even more opportunities and one is left with a man who played just 13 Tests. His record in those remains an impessive one. He averaged more than 60 and, in the nine Tests he played against England, north of 70. For all his high jinks Sid Barnes was a fine batsmen and at his best as close as anyone in his era got to Bradman. In the last Australian summer before the war he scored six centuries and averaged 75 in just eight matches. In the first season afterwards it was seven matches, five centuries and an average of 88.

In his earliest days Barnes was an aggressive stroke player and although he was never dull he did, with experience, cut out some of the shots that he felt presented unnecessary risks. He was a great admirer of Bradman and the key to his success was described in a 1948 pre-tour brochure as Barnes gets further behind the flight of the ball than any Australian batsmen except Bradman, and times his strokes to the split second. Whilst doubtless disapproving strongly of some of his antics Bradman in turn had a great deal of respect for Barnes. As well as his batting Barnes was a good enough wicketkeeper to take a share of those duties on the 1938 tour and was a very fine, and totally fearless, close fielder particularly at silly mid-on. If that were not sufficient his wrist spin repertoire, which included an excellent top-spinner, would doubtless have brought him many more than 57 First Class wickets at 32 had he had more time to devote to it.

After just one full season of Shield cricket Barnes came to England with Bradman’s 1938 side although, thanks to a broken wrist sustained on the voyage over, the tour was half over by the time he was fit enough to play. He made the Test side only for the final match at the Oval, where Hutton scored his 364 and England won by the small matter of an innings and 579. Australia, missing Bradman and Fingleton through injury, could make no impression on England’s massive 903-7 (Hammond finally declared only when assured Bradman was not fit to bat), but Barnes scored 41 and 33 and emerged from the wreckage with credit.

The next clash between England and Australia was eight years later in 1946/47 and Barnes was a certain starter and, apart from the fourth Test when an attack of fibrositis kept him out, he played throughout the series and averaged 73. At Sydney in the second Test he shared a fifth wicket stand of 405 with Bradman and went on to score 234, exactly the same score as the great man. He maintained he did so deliberately out of respect for his captain, although many doubted it were as simple as that. Rather more accepted that while Barnes might well have engineered his own dismissal, the reason would not so much have been his respect for Bradman as the commercial possibilities he saw in the situation.

It was the third Test of the series where the infamous turnstile incident occurred. It is utterly trivial in itself, but came back to life with a vengeance five years later. There are various versions of the story. Barnes own account was that he had met friends outside the ground to give to them the two complimentary tickets that he, as a player, was entitled to. He was not out overnight but, because he had forgotten his own pass into the ground, the turnstile attendant would not allow him into the ground nor would he send for anyone to vouch for his identity. Eventually Barnes took matters into his own hands and vaulted the turnstile and made his way to the dressing room. As he was padding up a member of the NSW Board told him he should apologise to the Chairman of the MCG. He refused, pointing out the absurdity of the alternative scenario of his being stuck outside the ground as the innings resumed. That, officially at least, was that for the next five years.

It has been said that in fact Barnes had sold not only his complimentary tickets but his own. On the other hand one of his teammates was adamant that in a spontaneous gesture of goodwill Barnes had given his own ticket to a frail old lady who was desperate to get into the match. Another variation has the attendant more than willing to let Barnes in, but just wanting him to provide a signature and Barnes not wishing to wait while a pen and paper were located. In any event what actually happens matters little – the dressing room snub was undoubtedly, to the extent that there was one, the key part of the incident.

The 1946/47 series over Barnes secured employment with a wine and whisky firm which involved travelling to England to promote their products. As his journey started Barnes heard that soap was in short supply in England. In keeping with his reputation as he left he sourced and took with him several hundred bars – they proved a useful investment. On arrival he also signed a lucrative contract to play as Burnley’s professional in the Lancashire League. To get his eye in before travelling north shortly after he arrived in England Barnes did ask the MCC for facilities to have a net at Lord’s – they declined – a snub that, as we shall see, Barnes did not forget.

Although Barnes did well at Burnley he retained the right to give a week’s notice to terminate the contract, a step he took part way through the season once he found that the club’s midweek games deprived him of a number of valuable business opportunities.

Professional contracts in English league and/or county cricket had spelt the end of any international career for the likes of George Tribe, Bruce Dooland, and Cec Pepper. Barnes must have expected problems in getting his Test place back particularly as he had also brought his wife and family to England with him and in addition that factor would potentially, conflict with the Board’s strict “no wives on tour” policy.

That Barnes Test career did not end in 1947 was largely as a result of Bradman’s decision to accept the captaincy for 1948. The effect of this was twofold. The first factor was that for Barnes there was the attraction of playing with his hero, and his willingness to make sacrifices to achieve that. Secondly, and equally importantly, was Bradman’s desire to go through the tour unbeaten and the consequent importance to him of having available the man who, after himself, was Australia’s best batsman.

Having made the decision to travel home alone Barnes did not arrive in Australia in time to reclaim his place for the start of the series against the touring Indians in 1947/48, but he was back for the third Test and did enough to ensure, given Bradman’s influence and his own promises about his family remaining in Scotland throughout the 1948 tour, to get on the boat to England with the Invincibles.

That Barnes was not entirely popular in England is clear. The normally effusive Neville Cardus felt the need to say of him in a pre-tour publication; Here is a cricketer of challenging character. He can be very annoying. His enemies – and he makes them indiscriminately – maintain that he is an exhibitionist.

In the first Test Barnes needled some as, following his scoring what he believed were the winning runs, he charged off the pitch, stumps gathered as souvenirs, only to find another run still needed. At Lord’s in the second Test he had his revenge after the snub from the previous year. Having backed himself to the tune of eight pounds at odds of 15-1 to do so he spent more than four hours in the second innings grinding out a century. Having got there he then took less than twenty minutes to add another 41 before being dismissed. Contemporary reports describe vividly the fire in his eyes as he looked towards the committee rooms as he reached three figures.

In the third Test Barnes had the headlines again albeit for different reasons. Having heard Denis Compton counsel his batting partner, Lancashire pace bowler Dick Pollard, to defend at all costs, Barnes was in his usual position as Ian Johnson tossed his off breaks up in an effort to tempt the man known affectionately as “t’owd chain horse”. Pollard disobeyed Compton and struck one delivery with such ferocity and timing that, had Barnes ribs not got in the way, it would surely have ended up out of the Old Trafford ground. As it is history leaves us with an image of Barnes being carried from the pitch, clearly in great pain, by four burly Police Officers. However great his pain was it did not prevent Barnes checking almost immediately with Bill Brown that he had captured the whole incident on film. Barnes’ reputation in Cardus country was not helped by his then choosing to bat next day, and retiring hurt and being carried off again after scoring just a single. He missed the fourth Test as a result of the injury but was back for Bradman’s finale at the Oval, and he ended up averaging 82 for the series. He did not play Test cricket again, but his story has a few twists yet.

As noted Barnes gave Australia’s next two series a miss and indeed one Testimonial match for Bradman apart, he did not play in a First Class match for the next three years. By 1951/52 though his appetite had returned and he wanted to play for Australia in their upcoming series against the West Indians, who had carried all before them in England in 1950. In the first two Tests Ken Archer opened the batting with Arthur Morris but did not do well. Barnes and Morris then posted an opening partnership of 210 in a Sheffield Shield game just before the selectors announced the side for the third Test and, his old captain Bradman amongst that committee, Barnes was named in the squad. The Board however vetoed the selection for reasons that, at the time, were identified as merely other than cricket ability

Barnes was met with a wall of silence as he tried to find out more until, in late April 1952, a letter appeared in the Sydney Daily Mirror. The paper had earlier published a piece strongly critical of the Board and then published a letter from a member of the public that, effectively, asserted that the Board would not have acted as they did without good reason and that Barnes ought to be grateful that they had not disclosed why they had done so. The author of the letter received a libel writ. He of course pleaded that his words were true and, as the law permitted him to do in light of his defence, subpeonaed the Board members to give evidence and the truth came out.

There were three reasons eventually teased out of the witnesses. The first was the turnstile incident that I have already dealt with. The other two both came from the 1948 tour. One was Barnes having taken photographs at Lord’s in the match between the tourists and Middlesex when the teams were presented to King George VI and Queen Elizabeth. Barnes had been told afterwards by the secretary of the MCC that he should not have taken the photographs as the club had sold all the ground’s filming rights to an agency. Barnes did not know that, and had earlier asked for and been granted permission by the club President, who clearly did not know either.

The second incident involved a game of tennis Barnes had had with teammate Toshack during play in the tour match at Northampton, the issue being that Toshack was supposedly twelfth man at the time. Four years on whether Toshack was in fact carrying out those duties whilst playing in the impromptu game was a moot point, but the issue hadn’t been raised when it occurred, and it was never established exactly what happened. But what the Board could not dispute was that at the end of the tour Barnes received his good conduct bonus in full and his behaviour on tour was reported as being exemplary. Not surprisingly the Defendant’s case fell apart and he settled on the basis that he agreed to pay Barnes’ costs, and his counsel made what amounted to a valedictory speech on Barnes’ behalf.

Unsurprisingly there is a good deal of material available on this case almost all of which seems to suggest it was a genuine piece of litigation. Sixty years on and from the other side of the world, with absolutely no new evidence to look at, I am not really in a position to comment, but surely the case bears all the hallmarks of a sham? The Defendant, Jacob Raith, was a past President of Barnes’ club, Petersham, and although he and Barnes both suggested otherwise they must surely therefore have been known to each other? Why was the Sydney Daily Mirror not joined as Second Defendant? Why was a proper attempt not made to accommodate the convenience of Bradman, uniquely selector and Board Member, to enable him to attend to give evidence? I wonder if Raith ever paid Barnes’ costs, or if they were picked up by the newspaper, or Wm Kimber and Co, who published Barnes autobiography the following year, or perhaps by Barnes himself? Indeed did Mr Raith ever pay his own costs? or were they paid by someone else? Perhaps, having practiced law for many years I am too cynical, but the whole thing seems like a put up job to me, although from what I have read the only man who had a real handle on what was going on was, perhaps inevitably, Sir Donald Bradman.

By the time the case came on for trial, by today’s standards indecently rapidly just under four months after Raith’s letter originally appeared, the West Indies series was over but, his eyes on the first South African visit for twenty years, and another Ashes trip immediately afterwards, Barnes had not given up hope of a last hurrah. He did all he realistically could to make it happen but, once it became clear he was wasting his time, his career finally ended shortly after the twelfth man in a lounge suit incident took place, when he started for New South Wales for the last time on New Year’s Day 1953 against South Africa, a game remembered for the full flowering of the precocious genius of Ian Craig, another man who never came close to fulfilling his potential.

That is not to say that Barnes was not in England in 1953 as he was, lampooning and lambasting in his own inimitable way through his newspaper column, and publishing a hard hitting account of the series after the tour . Barnes took no prisoners with his writing and declared that, had it not been for visits to nightclubs, the Australians would have won three of the Tests. He accused the team of socialising too much and being rude and disrespectful to their hosts. He was particularly harsh on his old friend Miller, who he said shirked his duties whenever there was a race meeting that he wanted to attend, and of malingering in order to be at Epsom for the Derby. The team also, according to Barnes, neglected net practice in order to prioritise business opportunities.

Barnes picked up much criticism for the content of his book and newspaper writings, and ruffled more feathers with his autobiography when that was published later in 1953. A further book on the 1954/55 series was more of the same. His writing and other business interests brought Barnes financial security but he seems never to have found real happiness. He suffered from severe depression and took medication and also underwent Electric Shock Treatment. Life in the Barnes household was later described by his daughter as “sheer hell” and his wife took refuge in the bottle. Finally in 1973 Barnes took an overdose of prescription drugs and died, aged 57, one of the not inconsiderable band of Test cricketers to have taken their own lives.

To stir Cardus to comment in the manner he did Barnes must have been a difficult man to like, but I believe that that was for reasons that were more a reflection of the prevailing English attitudes of the time in which he lived rather than any inherent character defects. I doubt he would have been such an enfant terrible were he playing today, and suspect that the best summary of him comes from a man who was the closest thing Australia produced to a kindred spirit to Cardus, Ray Robinson, who wrote in 1951; In all the criticism of Barnes for flagrant showmanship and cross-grained behaviour, the most severe comments come from those who knew him from afar, the least from cricketers who have played with and against him.

A great read. Always thought he was harshly treated by the powers that be.

They really thought of ridiculous reasons to exclude blokes back then. Bit like John Benaud and the rubber soled shoes in the late 60s-early 70s.

Comment by Burgey | 12:00am GMT 6 January 2012

The other great Barnes story was on the boat over in 48. The team did thousands of autograph cards on the voyage but Barnes CBF so he paid a cabin boy to sign for him.

Trouble was the lad spelt his name wrong so a batch of about 500 had to go overboard.

Comment by Burgey | 12:00am GMT 6 January 2012

Yet another gem Fred. 🙂

Still the second highest average of anyone with more than 1,000 Test runs. Pleased that Spikey mentioned that quote from Bradman – a great compliment, and one of the finest indicators of Sid’s ability.

Ernie Toshack said that Barnes was the best batsman he ever bowled to – and while Toshack never bowled to Bradman, it’s worth noting that he did bowl to Hammond (albeit past his best), Hutton and Compton, so this was high praise indeed.

Another for the “what might have been” files. 🙁

Comment by The Sean | 12:00am GMT 6 January 2012

It didn’t mention one Sid story though. Early on in the Invincibles tour Aus almost lost a low scoring match against Yorkshire. Bradman responded by saying ‘Either Sid or I will have to play every match’. And that pretty much happened (They both didn’t play in the Uni and minor county matches)

Comment by Spikey | 12:00am GMT 6 January 2012

My father, a quiet, unasssuming man and very competent cricketer, always told me that Sid Barnes was the best batsman he ever saw.

Thanks for a great summary of Sid Barnes\’ life.

Comment by Tim | 12:00am GMT 26 January 2012

Hi guys, nice to read some more about my grandfather (he died when I was one). My mum still tells me stories and his son, Sid Jnr, my uncle, is coming to see me tomorrow. Keep the stories coming!

Comment by Kirsty Sleep | 12:00am GMT 9 February 2012

I delivered some drinks to Alan McGilvray’s house back in the early 1990’s & being a mad cricket fan I loved talking with him. In regard to the 234 innings equalling Bradman’s on the same day, Alan said that Sid had a bet that he would equal the Don’s score that day & that was why he threw his wicket away, has anyone else heard this version?

Comment by Barry Joseph | 12:00am BST 20 June 2012