Rohan Kanhai

Martin Chandler |

They used to call him The Old Grey Fox in Warwickshire. I cannot now recall when I first saw Rohan Kanhai play but it was probably 1969, the year that the advent of the old John Player’s Sunday League first brought county cricket into the nation’s living rooms. Kanhai would only have been 33, but on the old black and white television sets of the time his hair looked very grey indeed and the assumption was that he was an old man. By 1973 we saw a good deal of him once more as captain of the successful West Indian tourists of that summer. My parents had a decent colour set by then. Kanhai’s hair was even greyer, but the superior picture quality now showed that was misleading, that he had a young man’s face, and a twinkle in his eye.

I always think that Kanhai is a little unlucky. He was an essential part of the West Indies side that narrowly lost in Australia in 1960/61, the series of the first tied Test, and then went on to beat India, England and Australia, followed by England and India again to be, by 1967, the undisputed kings of cricket. That they continued to play a brand of calypso cricket when the game was becoming increasingly dulled by the importance of avoiding defeat was a further reason why crowds the world over looked forward to seeing the men in maroon caps. Yet despite having a top class team there was just one man who seemed to soak up all the adulation, the remarkable Garry Sobers.

Despite what some thought, and as a cricket lover of the tenderest years I was most definitely guilty of that, Sobers was not the only great player in the West Indian team. Wes Hall is remembered as a great fast bowler, and Charlie Griffith has a certain notoriety, but Conrad Hunte, Seymour Nurse and Basil Butcher were fine batsmen. Lance Gibbs was one of the greatest off spinners of all time, but more underrated by history than all of them is Kanhai, a man who Sunil Gavaskar described in 1984 as quite simply the greatest batsman I have ever seen. And Sunny hadn’t forgotten Sobers either; as a batsman I thought Kanhai was just a bit better. Did the adulation that Sobers receive bother Kanhai? It seems that at times it may have done, and that more generally his emotions did occasionally get in the way of his batting but he was greatly respected within the game. Former county teammate and Test match opponent Bob Barber says Rohan was for me much the most difficult West Indian to bowl at. He was quick on his feet and almost always aggressive. A destroyer! I would say during that period (the mid 1960s) he was their and possibly the world’s best batsman.

Gavaskar, who was to name his son after Kanhai, explained his reasoning too. It went back to the series played out between Australia and a Rest of the World XI in 1971/72. After two comfortable Australian defeats Sobers inspired a comeback with an innings of 254 after the side he was leading conceded a first innings lead of 101. It is often spoken of as one of the greatest of all Sobers’ innings and by some as the best of them. Gavaskar was opening the batting for the Rest in that game, and he had done so in the previous match as well when his team had subsided to a desultory 59 in their first innings in the face of an inspired spell from a very young and very fast Dennis Lillee, who took 8-29 on his home turf. The Rest lost by an innings but not before Gavaskar had had the privilege of watching Kanhai produce a magnificent counter-attack; He just smashed the ball to all corners of the field and scored 118. I’ve seen quite a few century innings, but that, in my mind, ranks as the best century I’ve ever seen. For sheer guts, for sheer technique and for the sheer audacity of his shots.

As to his background Kanhai’s grandparents had travelled from India to what was then British Guiana as indentured labourers to work in the sugar plantations. His father earned a living by buying and selling rice. The future batting icon was born on Boxing Day of 1935 in the village of Port Mourant, a community that produced a remarkable number of top class cricketers. An area of many fewer than ten thousand souls was also the birthplace of Test men Basil Butcher, Joe Solomon, Alvin Kallicharran, John Trim and Ivan Madray .

The attention of the wider world fixed upon the 19 year old Kanhai in only his second First Class match, against the touring Australians of 1954/55. The home side were heavily beaten but Kanhai scored 51 and 27 and was described by Australian writer Pat Landsberg as a dapper young Indian who showed no misgivings at the reputation of the Australians. Years later the Australian captain, off spinner Ian Johnson, wrote it was evident to all the Aussies in that game that Kanhai’s anonymity would be short-lived.

There were centuries for Kanhai in both of his First Class innings in 1956/57 and after just five First Class matches in all he was selected to tour England in 1957. The trip was one long disappointment for the tourists who were beaten 3-0 in the Tests and were not all that far from being whitewashed. Kanhai did not do particularly well, averaging just 22.88 with not even a half century to show for his efforts. But there were plenty of extenuating circumstances. First of all he was asked to keep wicket in the first three Tests, and to open the batting in two of them. Despite that he managed to top score twice in the series, and three times he passed 40 so, in unfamiliar conditions and with experienced colleagues all around him failing there was no blame to be attached to Kanhai for his side’s poor showing.

Less than six months after the return from England Pakistan toured the Caribbean for the first time and there was a steady if unspectacular increase in Kanhai’s productivity in that series. His real breakthrough came the following year when West Indies toured India and Pakistan, the turning point coming in the third Test of the Indian series at Eden Gardens. The Indians were not a strong side and lost the series 3-0, but they did have one world class player, the leg spinner who most of his contemporaries, including Kanhai and Sobers, maintain was a better leg spinner even than Shane Warne, Subhash ‘Fergie’ Gupte.

In the first Test Gupte ended Kanhai’s second innings and went on to dismiss him twice in the second Test. A self-confident man Gupte at one point wandered up to Kanhai and greeted him with Hello Rabbit. Through gritted teeth Kanhai’s reply was just you wait until next time. West Indies winning margin at Eden Gardens was an innings and 336 runs. Skipper Gerry Alexander won the toss and chose to bat and with Sobers unwell Kanhai was in at first drop. His highest Test innings to that time had been 96, which he easily surpassed, being unbeaten on 203 at the close. Next day he went on to 256, a score that was to remain his highest in Tests.

From Eden Gardens onwards Kanhai was always one of the leading lights in the West Indies side and it was to be a decade before he went through a series without an average in excess of 40. In Australia in 1960/61, the series of the first tied Test, he captured the imagination of the home supporters to such an extent that he was signed by Western Australia for the following season’s Sheffield Shield campaign. Before the Tests began a superb 252 against Victoria at the MCG was praised by all who saw it, and once the series got underway there were twin centuries for Kanhai in the fourth Test, a match which would have seen a West Indies win that would have squared that famous series had not ‘Slasher’ Mackay and last man Lindsey Kline hung on for almost two hours to secure the draw.

There was never any shortage of confidence on Kanhai’s part, and he wrote in an early volume of autobiography, I never doubted my batting ability from the day I could first hold a piece of wood between two small grimy hands. There were plenty of superlatives used when describing Kanhai the batsman. In that 1960/61 series ‘Tiger’ O’Reilly, by then a respected journalist, wrote, he constantly accepts the risks involved in hitting into the ball, but his bat moves at such unusual speed that even if he does miss-hit, the ball generally is bound to fall safely out of danger from the in-fieldsmen……He had a wide range of shots and an unremitting urge to use every one of them as often as possible

That speed of scoring, and the quality of the strokes are crucial issues where descriptions of Kanhai are concerned. John Arlott commented that for sustained, high-speed and flawless striking of the ball, no post-war batsman has scored quite so hectically against top-class bowling. Arlott’s Test Match Special colleague Trevor Bailey, not a man given to extravagant praise, expressed the view that his magic stems from a wonderful eye, lightning reflexes, footwork, and perfect timing. He has the ability to take an attack apart.

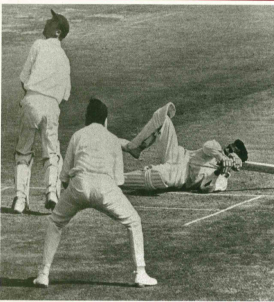

As with many a great batsman there was one particular shot that was associated with Kanhai, but unlike the Hammond cover drive, the Bradman pull and the Compton sweep none tried to emulate it, and even now with various limited overs formats forever pushing the limits of the imagination of innovative coaches the falling hook has never caught on. It was however, particularly in his early days, a feature of Kanhai’s batting. More of a sweep cum pull than an authentic hook the trademark finishing position saw Kanhai horizontal on the pitch as per the image that accompanies this feature. But the shot was not designed to produce the fall, in Barber’s words; Rohan was no ‘show pony’. He was a small light man who on those occasions had simply put all his energy and strength into hitting the ball.

Although his bowling was limited to occasional spells of fairly innocuous medium pace, and his wicket keeping functional rather than flamboyant Kanhai was a fine all round fielder. He had a superb throw from the deep and was quite capable of pulling off the most spectacular of catches. On one occasion when he caught Bob Simpson from a full-blooded leg glance Jack Fingleton was sufficiently impressed to write that he moved like a black mamba, famished after hibernation, on sighting its first prey. He rested at last with the ball held in an arm raised up like a signal.

After the visit to Australia in 1960/61 the Indians, this time in the Caribbean, were the next to feel the full force of Kanhai’s broad blade and he demonstrated it to all England in the vintage summer of 1963. Oddly he did not record a century, but there were four fifties and an average of more than 55. In the final Test at the Oval Kanhai took his side to victory with a very rapid 77, which caused JS Barker to observe that he pulled, hooked, drove and cut with a brilliance of timing audacity and stroke play which had the commentators hoarsely struggling to find epithets.

There could be no doubt by the end of 1963 that Kanhai was one of the best batsmen in world cricket, but he had still to be tested against unremitting pace from both ends, something that was inevitable given that in those days all the really quick bowlers were West Indian. In February 1964 however, as a member of the British Guiana side, Kanhai faced a Barbados attack led by Wesley Hall and Charlie Griffith, who had wreaked such havoc in England just a few months before.

British Guiana had a disastrous start as they slipped to 13-3, their first three batsman being dismissed by Hall and Griffith. The pair were, on their home wicket at Kensington Oval, at their most fearsome. To make matters worse Kanhai was bowled by Griffith before he had scored, but it was a no ball. Griffith cursed his ill-luck and bounced Kanhai repeatedly for the rest of the session but over three hours Kanhai fought fire with fire. Hall got him eventually, but not before the little man had scored 108 with as many as 17 boundaries, three of them from consecutive deliveries in one Hall over. Kanhai didn’t get to the crease in the second innings of the drawn game and never played against the pair again, but he had won the battle and shown that even extreme pace held no terrors for him.

Another Kanhai innings that seems to have particularly impressed is one from 1964. At the end of the season what amounted to a full West Indies side played three “festival” matches against an England XI at Scarborough, Edgbaston and Lord’s. The weather ruined the Lord’s match but Kanhai, who had been playing league cricket all summer, scored 170 at Edgbaston, an innings that CLR James wrote took him into regions that even Bradman never knew.

The mid 1960s were difficult times in British Guiana. Independence and the modern state of Guyana were just a couple of years away and in the lead up to independence there were problems aplenty. The two leading politicians in the country were the Afro-Caribbean Forbes Burnham and the Indo-Caribbean Cheddi Jagan. They had begun as allies but ended up as the two opposing potential leaders. The ultra left wing Jagan eventually lost out to the US/UK backed Burnham and there was a split down racial lines that caused historian Clem Shiwcharan to write of Kanhai’s rousing top score of 89 in the Georgetown Test against Australia in April 1965; we were lifted by Kanhai’s performance. In the midst of the imperious gloom and Burnhamist terror, we were saying ‘Fuck you! Today’s victory is ours’. A rather more objective source was Richie Benaud, who described it as one of the finest innings in modern-day Test cricket.

In 1968 the English counties were finally permitted to sign overseas players on immediate registrations. Kanhai joined Warwickshire and he served the West Midland county for a decade. There were too many fine innings along the way to dwell on them all but four warrant special mention, the first in that initial season.

Warwickshire visited Trent Bridge in June to play Nottinghamshire, who had secured what the press considered to be the biggest prize of all, Sobers. The great man won the toss and in good seaming conditions invited Warwickshire to bat. After 51 tortuous overs the visitors were bowled out for 93. The star of the show was not Sobers, who surprisingly went wicketless, but honest journeyman Mike Taylor whose medium pace brought him the impressive figures of 6-42. The home side secured a lead of 189 before reducing Warwickshire’s second innings to 6-3. At that point the East Midlands men must have been contemplating a comfortable victory, and Kanhai was the next man to fall. But not until he had scored 253, and added 402 with Billy Ibadulla to leave Notts content to play out time for the draw.

Two years later 1970 was a vintage year for Kanhai. He averaged 57.39 and scored seven centuries. The second of them was against Kent at Gravesend. Derek Underwood was at the peak of his powers in those days, and ended up with seven wickets in each innings. Despite a pitch tailor made for their greatest asset Kent still lost however. When Underwood came on in the first innings Kanhai welcomed him into the attack with a six, and then proceeded to score 107 out of 204, the match winning contribution. Against Derbyshire at Coventry a couple of months later Kanhai was on 63 with just four wickets to fall and no significant batting to come. He suddenly realised he was in danger of rapidly finding himself the last man standing. He did end up with that distinction, but not before a further 126 runs were added – 124 of them came from Kanhai’s bat.

Six years further on and Gloucestershire were the visitors to Edgbaston in a season when Championship regulations limited a side’s first innings to 100 overs. Opener Neal Abberley was dismissed in the first over of the day for a duck, but when the forced closure came John Jameson and Kanhai had added 465 for the second wicket.

By this time Kanhai was 40 and his Test career had been over for more than two years. He had, in 1972/73 finally been made captain of the West Indies after Sobers had to withdraw following a combination of some disappointing results and fitness compromised by a cartilage operation. The first Guyanese to captain the West Indies Kanhai was the obvious choice as Sobers’ successor and he was credited with forging a good team spirit and being tactically sound if, when pushed, a little on the defensive side. The contrast was particularly obvious in comparison with his first opposite number, Australia’s Ian Chappell. That series was lost 2-0, but the over-worked Lance Gibbs apart the attack at Kanhai’s disposal in what was very much a side in transition gave him little scope for experiment, or confidence in bowling Australia out twice.

In England a few weeks later it was a different story and Kanhai led his side to a convincing 2-0 victory to end the Ray Illingworth era. He was assisted by the return of an in form Sobers, but many of the younger players made great strides as well. There was controversy as well as Kanhai, who had been fielding at first slip, did not conceal his displeasure at a decision made by umpire Arthur Fagg not to give Geoff Boycott out caught behind. Fagg did not return to officiate the next morning as he sought an apology. He didn’t get one, although after an over’s play was persuaded to return. It was an unfortunate incident and Kanhai was clearly in the wrong whatever the status of the alleged snick, particularly as the fact that Sobers at second slip did not appeal would tend to suggest that Fagg was right. Whatever the rights and wrongs of that particular incident it does however demonstrate how deeply committed Kanhai was to the success of his side.

In truth Kanhai went on for one series too many, as he led West Indies in the drawn series in 1973/74. His average was down to 26.16, its lowest since his debut series against the same opponents 17 years before and his highest score was just 44. Despite that he was still sufficiently highly regarded, particularly in light of his experiences in England, to be picked in the squad for the first World Cup that took place in England in 1975. He made no contribution of note in the early matches but in the final, after his side had stumbled to 50-3, Kanhai kept his successor as captain, Clive Lloyd, company whilst 149 were added and when he was eventually out for a, by his standards restrained 55, the West Indians were well on their way to their winning total of 291.

The World Cup won Kanhai went back to Warwickshire and averaged more than 82 and he was back again in 1976 and 1977. They were however years of decline and in his final year Wisden described Kanhai as being a shadow of his former self, distracted by his benefit and plagued by injuries. There was one match in which he rolled back the years though, sadly for me against my county Lancashire. He scored 176 in a match that Warwickshire won by an innings. He was by all accounts particularly severe on the very wild but very fast young Guyanese bowler Colin Croft who had enjoyed a spectacular introduction to the Test side just a few months earlier. Perhaps there was a word or two exchanged between them, as a result of which Kanhai felt the need to demonstrate to his countryman that bowling fast wasn’t always easy.

Rohan Kanhai. In the words of Bob Barber it was a privilege to see him, a proud man and a wonderful player.

Hi I am fom South Africa.

My grand dad is an old friend of Rohan kenhai.

Any idea where ican get his contact info.

Thank You.

Comment by Nabil Garda | 2:01pm GMT 15 December 2015

truly a great;great player.Deserves a lot more credit than what he has been given.Surely the greatest batsman of the sixties when he was the automatic first down batsman in any world eleven team.

Comment by bharat tiwari | 5:48am GMT 15 February 2016

can i plz get contact info for Mr Kanhai. He has always been my idol growing up in Guyana nand after he left i hardly followed WI cricket. I have always wondered why the Queen never knighted him after all he was skip for her charity team.

Comment by ram | 8:42pm GMT 8 March 2018

Why was’nt Rohan knighted??. A good question.

His book “Blasting for Runs” cannot be found anywhere.. Could you tell me where I can find it?. In the meantime 85 not out and still blasting. A Guyanese legend.

Comment by Rob | 5:01pm GMT 15 March 2021