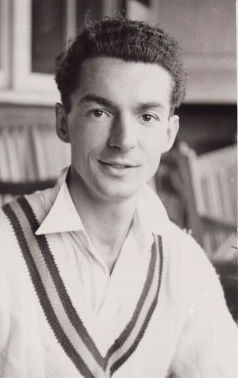

Almost But Not Quite – The Story of Reg Simpson

Martin Chandler |

When he died in 2013 Reg Simpson was the senior England Test cricketer, a title that had passed to him three years earlier on the death of Sir Alec Bedser. In his day he was considered one of the most stylish batsmen in the game, and played for England in 27 Tests. He is noted for one of the great innings in Ashes contests, at the MCG in February 1951, and there were three other Test centuries but, overall, Simpson’s returns at the highest level were relatively modest and, in the opinion of many contemporaries, did not truly reflect his ability.

An opening batsman despite his aggressive nature, Simpson’s reputation was as a peerless player of pace bowling. He was largely a back foot player, contrary to the views of most coaches at the time, but something he learnt when playing against the likes of Harold Larwood and Bill Voce in benefit matches in the late 1930s. On the other hand, certainly early in his career, his technique against spin bowlers was less than perfect, although in time he learned to watch the ball in the air rather than as it left the bowler’s hand and lost much of his uncertainty. He also suffered more than most from never being given the confidence boost of a long run in the England side, and he had the misfortune to emerge at the same time as Cyril Washbrook and Len Hutton forged their famous opening partnership. Simpson also struggled to play his natural game in Tests, never forgetting an incident when, against South Africa in 1951 he hit off spinner Athol Rowan over the top on his way to a century and was, he felt, admonished by his batting partner, future skipper Hutton reminding him he was playing in a Test match.

Unusually for a man who went on to achieve Test honours Simpson was born into a family that had no background or particular interest in the game, so he was largely self taught. Successful at school Simpson’s first job was as a cadet with the Nottingham City Police Force, who had a side he graced with distinction in the Nottingham and Derby Border League. Simpson was an excellent all-round sportsman who was to play Rugby Union at county level, and his mobility made him a fine fielder in the covers. No more than an occasional off spinner with the ball Simpson is nonetheless one of the few to have opened both the batting and the bowling at Test level. In 1951 with the first Test against New Zealand drifting towards an inevitable draw he shared the new ball with Washbrook in the New Zealand second innings and took two wickets for four runs in his four overs.

As a result of the Second World War Simpson did not make his First Class debut until he was 24, and all of his first six matches were played in India where, as an RAF Flight Lieutenant he was posted to fly for Transport Command. There were as many as six half centuries in Simpson’s ten innings, but he was unable to go on and convert any of them.

The reputation forged in wartime cricket meant that, as soon as he was demobilised in July 1946, Simpson was invited to play for Nottinghamshire. The committee wanted him to play for the first team immediately. When Simpson himself expressed some concern at that, on grounds of being hopelessly out of practice, he was parachuted in to bat at three in the second innings of a second eleven game and, 42 brisk runs later, took his place against Somerset the following day. He scored 29 in his only innings, so a reasonable return. After that however his next ten innings brought just 82 runs, and his confidence was low.

At the end of July Warwickshire visited Trent Bridge, and finally Simpson made the breakthrough. He got a few runs before lunch, and was then told by teammate Joe Hardstaff to get his head down. Simpson took the advice and was eventually ninth out for 201. He had arrived, and whilst he did not score another century that summer there were a couple more decent innings to show that the double century was no fluke. His ambition to become a commercial airline pilot went on hold, as things turned out permanently.

Having established that he was good enough to play at First Class level Simpson wanted to play as an amateur and initially in order to do that was employed by the club as Assistant Secretary, a means by which several amateurs were able to play full time cricket. Simpson also had ambitions outside the game, so the Assistant Secretary job lasted only until he was able to secure employment with the famous local bat makers, Gunn and Moore. The position was no sinecure however as Simpson stayed with the company for the whole of his working life and there he certainly got right to the top, eventually being appointed managing director.

In his first full season in 1947 Simpson did well and in 1948 innings of 74 and 70 for Notts against Don Bradman’s Invincibles, including both of Keith Miller and Ray Lindwall, made many sit up and take notice. Selected for the first Test ten days later Simpson was left out on the morning of the match. His form for the rest of 1948 was a little patchy but, as the selectors became increasingly desperate as the defeats went on there were many who were surprised that such a fine player of quick bowling was not given another chance. In the event he was not picked again until the final Test at the Oval, when he was once again made twelfth man. Consolation came with a place in the party to visit South Africa that winter.

There was a Test debut for Simpson in South Africa, but scores of 5 and 0 were not enough to keep him in the side and that was the only one of the five Tests he was selected for. The following English summer was the real breakthrough however as Simpson scored 2,525 runs at 63.12. This was the summer when Notts decided to break up their long established opening partnership of Walter Keeton and Charlie Harris and Simpson stepped up into what most considered his natural position. At one point in the summer he and Keeton made four consecutive century partnerships, and Simpson was recalled to the England side for the third and fourth Tests against New Zealand.

The ‘forty niners’ were a strong side, particularly in batting, and all four of the three day Test matches were drawn. In the third Test, batting at five, Simpson scored 103 the second fifty coming, as England tried to force the pace, in less than half an hour. In the absence of Washbrook in the final Test he went in first with Hutton, and contributed 68 to an opening partnership of 147 in two and a half hours, so showing a degree of restraint.

With no England tour in 1949/50 Simpson was the man in possession when West Indies visited in 1950 and he appeared in three of the four Tests, missing the second with injury. In the third at Trent Bridge he made his one major score, 94, in a 212 run opening partnership with Washbrook. A few runs later he was run out going for a sharp single in an attempt to prevent the new batsman Gilbert Parkhouse from having to face Sonny Ramadhin and, according to John Arlott, had well earned a century, although Arlott also observed that he had batted with less freedom than he did for Notts.

Outside the Tests Simpson had a fine summer finishing second in the averages and, with 2,576, was the leading run scorer in the country. He recorded the highest score of his career to that date, an unbeaten 243 against Worcestershire, and another double century as well as six more singles as he averaged more than 85 in the Championship. Confirmation of his inclusion in the 1950/51 Ashes squad must have been one of the easier decisions made by that year’s selectors.

With the exception of Hutton, who in averaging 88.83 for the series was absolutely magnificent, the England batting in 1950/51 proved lamentably weak. Washbrook and Denis Compton had dreadful series and initially Simpson struggled as much as his teammates against the pace attack of Lindwall, Miller and Bill Johnston, all still near their peaks, and the mystery spinner Jack Iverson. Wisden described him as becoming hesitant and uncertain. There were signs however, as the series went on, that that confidence was returning. There was an innings of 49 in the third Test, one of 61 in the fourth and then, with England 4-0 down and looking very sorry for themselves, Simpson was the inspiration behind an unexpected victory in the final Test, England’s first over Australia since 1938.

The Australians won the toss and chose to bat at the MCG where, thanks to the medium pace of Alec Bedser and skipper Freddie Brown, England were able to dismiss them for 217 early on the third morning (the whole of the second day having been lost to rain). In reply England lost Washbrook at 40 but after that Simpson and Hutton batted calmly through to the tea interval at which point they were 160-1 with Simpson on 49. He had batted well but his caution was demonstrated by the fact he had hit only three boundaries.

After tea Simpson duly got to fifty, but at 171 Hutton was dismissed. By the end of the day England had, by just a single run, taken the lead but had lost six wickets in total. Simpson had had a difficult few overs after Hutton’s dismissal, and although he got over that he could not do anything to raise the scoring rate and added just three to his score in the last 57 minutes of the day. He was unbeaten on 80 at the close.

On the fourth morning Simpson seemed no more able to force the pace than he had the previous evening and when the ninth wicket fell England were just 29 runs in front, nowhere near enough with Iverson bowling at them in the fourth innings. At this point Simpson was joined by off spinner Roy Tattersall, most definitely a tailender. Having added just a dozen runs to his overnight score it seemed unlikely Simpson would even reach his century.

Realising he now had no choice Simpson started to attack the bowling and in a famous partnership he and Tattersall added 74 before Miller finally got one through Tattersall’s defences and bowled him for 10. By then Simpson had moved his own score on to 156 and the lead of 103 turned out to be plenty and England ran out winners by eight wickets.

It is worth quoting the former Australian opening batsman turned respected journalist Jack Fingleton at some length. In his account of the 1950/51 series, and Fingleton had also been in England in 1948, he wrote; Simpson was an enigma. Australians who had seen him in action in England in 1948, and against our best fast bowling, thought the English selectors should have played him in all five tests. He played in none.

As I saw him over this tour, Simpson had only one weakness and that was himself. He lacked confidence in the strangest possible manner. Without reservation, I would place Simpson among the greatest stroke makers I have seen in cricket. No batsman today has more strokes than Simpson, no batsmen can better him in footwork yet, for innings after innings, Simpson anchored his feet in the crease and made ordinary slow bowlers look like monsters. Fingleton closed with the observation that; the trouble with Simpson is that he is a much better batsmen than he thinks he is.

In 1951 Simpson took over the Notts captaincy, a job he did for the next decade. The squad wasn’t the strongest, and it had to play half its matches on the lifeless wicket at Trent Bridge. In those ten summers six saw the county in the bottom three places and only three times did they reach the top ten, with a best of fifth in 1954. Despite the problems he encountered Simpson was certainly an advocate of brighter cricket. In that first season with the captaincy he became so irritated by the slow progress of a match against Glamorgan that he brought himself on to bowl an over of lobs at his opposite number, Wilf Wooller. A robust character himself Wooller did not appreciate the move and, after taking two runs from the first delivery, pointedly blocked the other five, mopping his brow after each delivery. So Simpson’s gesture made little difference to the funereal pace of the game, but it did at least prompt his County committee to announce that they would be taking steps to speed up the pitches at Trent Bridge.

England’s visitors in 1951 were the South Africans and Simpson made good use of his benign home pitch in making 137 in the first innings of the first Test. After that and his innings at the MCG the previous winter scores in the next two Tests of 26, 11 and 4*, both of which, unlike the first Test, were won, were not sufficient for him to be retained for the remaining two Tests.

In 1952 Simpson played in the first two Tests against India, and scored a half century in each of his innings, but the selectors were in the mood to experiment against weak opposition and the Reverend David Sheppard was preferred to him for the remaining two Tests. Simpson was back in 1953 for the Ashes but, in a series where few scored heavily, he did not get more than 31 in an innings and missed two of the Tests. Outside the Tests however he did very well and scored 2,505 runs in all cricket. He went on to do well on a return to India with a Commonwealth XI, but he had not done enough to get a place with the England party that toured the Caribbean in early 1954.

The summer of 1954 was not a good one overall for Simpson, but he got a place in the England side that faced Pakistan and, had he not missed one match injured, would probably have bee selected for all four Tests. His century in the second Test was enough to earn him another chance in Australia as part of Hutton’s powerful 1954/55 combination. Simpson turned 35 during the tour which, successful though it was for England, turned out to be his personal swansong in Test cricket.

The first Test of the series gave no hint of what was to come as Hutton, on winning the toss, made the disastrous decision to ask Australia to bat. The 601-8 they amassed was enough for a victory by an innings 154. Opening with Hutton Simpson scored 2 and 9 and did not play in the rest of a series dominated by the bowling of Frank Tyson. It must have been frustrating in the extreme for him to watch Trevor Bailey, Bill Edrich and Tom Graveney, none of them regular openers, tried in turn as Hutton’s opening partner. He did get his place back in New Zealand, contributing 21 and 23 to two comfortable wins.

With Len Hutton retiring from Test cricket in 1955 there were two vacancies at the top of the England order so Simpson must have hoped his Test career would continue. Unfortunately for him however he did not have a particularly good summer, and was not therefore one of the six openers who were at various times tried. Only Graveney, not an opener by upbringing or inclination, made very many runs, so the same problem loomed for the visit of the Australians in 1956.

It must be that the selectors still had Simpson in mind in 1956 as they invited him to lead the MCC side that played against the Australians at Lord’s early in the tour. There was certainly no ageism amongst the selectors that summer as the later recalls to the colours of Compton and Washbrook demonstrated, but Simpson managed only 13 for the MCC and whilst no other openers came to the fore the selectors, not for the only time, persuaded Colin Cowdrey to leave the middle order as a result of which he and Peter Richardson were able to do enough to secure the opening partnership for the series. It was a great shame that Simpson could not maintain for the rest of the summer the form he showed in the first match of the season when he rolled back the years to dominate a Notts innings of 278 with 150 from a Northamptonshire attack that included Frank Tyson.

For the rest of his career there was to only be county cricket to inspire Simpson. He enjoyed a good summer in 1959, scoring 2,000 runs for the last time, but that apart the closing years of the 1950s saw, not unnaturally for a man in his late thirties, a dip in his effectiveness and he handed over the reins of captaincy for the 1961 summer to John Clay. Although in the dozen games Simpson played under Clay he scored his runs at not far short of 30 the new skipper could do nothing to lift the county’s fortunes and they finished last again.

In 1962 there was a slight improvement in Notts’ fortunes as under the leadership of bowling all-rounder Andrew Corran they moved up a couple of places in the table. Again Simpson was an occasional luxury and this time one that enjoyed an Indian summer, topping not only the Notts batting averages but those of the whole country with 867 runs at 54.18. In the circumstances he could hardly be blamed for turning out occasionally in 1963 but that proved a mistake as his average fell to less than 20 and there was not even a single half century to go out with, although at least, under their fourth captain in four years, wicketkeeper Geoff Millman, Notts rose to ninth in the Championship. It would not be too long before they were a power in the land once more and Simpson did play his part in that rise, spending 35 years on a committee which, amongst other things, brought the likes of Garry Sobers, Richard Hadlee and Clive Rice to the club.

At a less rarefied level Simpson continued to play the game in addition to running Gunn and Moore, and well into his sixties was turning out for The Forty Club and the Lord’s Tavernor’s. Outside the game he continued to work with the RAF Auxilliary Force helping to train young pilots. Perhaps in his life Reg Simpson took on just a little too much as he was married as many as three times. He had two daughters by his first marriage, which ended in divorce. His second wife died of cancer and then when he married for a third time that marriage too ended in divorce, although despite those setbacks he enjoyed good health for more than nine decades.

Leave a comment