Ranji and Ollivierre

David Mutton |

July 1904: a drab, damp county championship game at the County Ground, Derby. The home side bowled first and was kept in the field for most of the first two days as Sussex progressed in slow , stolid fashion. Ten bowlers, all but the wicketkeeper, turned their arms over until C.B. Fry finally declared the innings closed on 363 for 4. In response Derbyshire could only muster 25 for 2 before the rain came, washing out the rest of the game. A tedious, uneventful match, lost to history. But on one side was an Indian prince and on the other a black batsman from the tiny island of St. Vincent.

This was not the first time that foreign-born players featured in English domestic cricket. Australians such as Albert Trott and the ‘Demon’ Spofforth had stayed on in the country after tours, and there was even a mixed-race South African, Charles Llewellyn, in the Hampshire side around the turn of the century, although he vehemently proclaimed the whiteness of his skin. The main opportunities for Victorian English public to see non-white cricketers were the Australian Aboriginals tour of 1868, two teams of Indian Parsees in the 1880’s and a West Indian side in 1900.

It was on this first West Indian tour that Charles Ollivierre came to Britain. Rated as the best batsman in the side and a useful bowler, Ollivierre finished the tour with the most runs and the highest batting average. Wisden praised his “strokes all around the wicket” and thought him “particularly strong in cutting and playing to leg”. Derbyshire, who finished third from bottom of the championship table in 1900, saw in Ollivierre an opportunity to strengthen their batting. However Lord Harris’ rigid policy of qualification meant that it would be two years before Ollivierre played in the championship, during which time he lodged in Glossop and played for the town’s side in the Lancashire League.

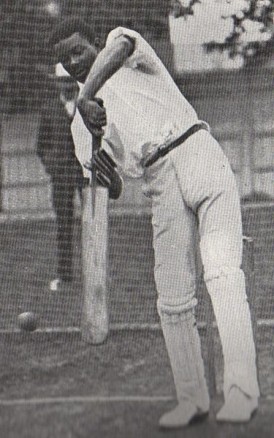

Ranjitsinhji’s route to that tedious game in 1904 was altogether different. Born into a noble Indian family, he first came to England in 1888 and entered Trinity College, Cambridge the following year. It was only at university that he started playing cricket seriously, and developed a new shot, the leg glance. Stanley Jackson, the varsity captain, was shocked when he first saw Ranji play the shot. To his establishment mind the only acceptable response to a well-directed delivery was to tap it politely back to the bowler. Anything else was verging on immoral, and such decadent play was almost certainly a reason why Ranji was not awarded a blue until his second year at Cambridge.

Such innovation was one of the most important qualities that both he and Ollivierre brought to the English game. Batting belonged to amateurs, many of whom learned their game at Harrow or Eton during a time when sport was seen as an opportunity to develop the character of a Victorian gentleman. It is not surprising that it took W.G. Grace, another batsman who did not go to a public school, to develop batting in new directions. While we know less about Ollivierre’s style, he too appears to have approached batting differently than his county teammates. Arthur Knight describes him batting with a “certain allusive nuance, suggestive of a far away glamour which no English player possesses”.

Their distinctive, flamboyant styles made Ranji and Ollivierre crowd favourites. A week before the game against Derbyshire, Ollivierre was instrumental in one of the best results in Derbyshire cricket, described by Wisden as “the most phenomenal performance ever recorded in first-class cricket.” Responding to an Essex total of 597, Ollivierre hit a double century to help Derbyshire to 548, before they skittled the southerners for 97. In the final innings the West Indian scored 92 not out to ensure that they achieved a remarkable victory. The newspapers reported “one of the greatest ovations ever given to a Derbyshire batsman” as Ollivierre walked back to the pavilion.

There was undoubtedly a large degree of exoticism surrounding Ranji’s popularity, with his status as an

“Indian prince” and his lavish lifestyle (which left him perpetually in debt) encouraging images of an opulent Raj. His phenomenal first season for Sussex brought him to national attention, and soon his name alone drew larger crowds, with people gathering around grounds hoping to catch sight of the master batsman. As importantly he gained the approval of the Establishment, with a celebration in Ranji’s honour at the end of the 1896 season attended by the master of Trinity College, 2 members of parliament and 300 other dignitaries.

This popularity masked the challenges that faced the two batsmen in England. The theories and notions of racial superiority upon which the Empire was based crossed over into the sporting realm. Lord Harris loomed large in these strange assumptions, with comments such as “wear[ing] down good bowling is easier for the phlegmatic Anglo-Saxon than the excitable Asiatic”. The Telegraph described Ranji as possessing “wrists supple and tough as a creeper of the Indian jungle, and dark eyes which see every twist and turn of the bounding ball.” It was Lord Harris who delayed Ranji’s test debut, refusing to select him against the Australians at Lords in 1896. Ultimately the prospect of attracting more people through the turnstiles won out when he was picked for the next test at Old Trafford (at the time the ground committee selected the side). Less is known about Ollivierre but at least one of his colleagues, Bill Storer, was apparently “not fond of importations, especially of the ebony hue”.

Ranji and Ollivierre were pioneers long before the era of mass migration. On the field they could play as equals, and through their exceptional talent they won the affection of the English public at a time when the vast majority of people had never seen an Indian or a black man. That they achieved this against a background of racism, social Darwinism and plain ignorance is remarkable. On their shoulders sit generations of cricketing migrants who have come to England to grace the game.

Enjoyed this piece. Ranji was the subject of a very good book by Alan Ross, and Olivierre features in the excellent ’50 Incredible Cricket Matches’ by Patrick Murphy – the match in which Derby beat Essex after Perrin hit 343.

Comment by stumpski | 12:00am BST 23 September 2013

Thanks for the heads-up on the Pat Murphy book (he seems to have written/ghost written thousands of books). I have read the (I think) most recent Ranji biography, by Simon Wilde, which is also very good.

Comment by David Mutton | 12:00am BST 2 October 2013