Not Cricket: Hansie Cronje

Gareth Bland |

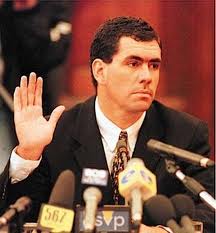

All is rosy in the South African garden at the moment. A successful tour of England this summer has left them top of the tree in two of the three formats of the game, usurping this summer’s opponents in the process. That same rosiness, perhaps, implores us to reflect on just how far South Africa has come since its international isolation came to an end in 1991-92. It has certainly been an interesting journey. Since that return to the international fold in India in November 1991, when an openly emotional Clive Rice and his team soaked in the applause from the Kolkata crowd, it is Hansie Cronje who has filled the space as South African cricket’s most divisive figure in that time, achieving a notoriety that transcended the game itself. The man who was voted the 11th greatest South African ever in 2004 has had his life captured on celluloid in a film Hansie, with, in the ten years since his death, revisionists in turn castigating and eulogising the man who met his end at the age of 32 in 2002.

Nowhere, in fact, has the cult of Cronje been so scrutinised than in the BBC4 documentary, first broadcast on UK television in 2008 Not Cricket: The Captain and The Bookmaker, written by Paul Yule and Peter Oborne and narrated by Oborne himself. Oborne, occupying the position of British journalism’s iconoclast-in-chief alongside Peter Hitchens, has previously gone on air to excoriate the pro-Israel lobby in the House of Commons, as well as being famed for his antipathy toward the European Union, denouncing one hapless bureaucrat as “that idiot in Brussels” while live in the Newsnight studio. In 2008, however, his target was the former South African cricket captain. Yule and Oborne’s Cronje expose followed up their Basil D’Oliviera documentary, broadcast as part of the same Not Cricket short series. What is revealed is a man who had an incredible competitive urge from boyhood, encouraged and mentored by his loving parents, Ewie and San-Marie. They were a couple who had inculcated in their strong-willed son “very good values” in the words of South African cricket writer, Krish Reddy. Other salient factors become clear, too. Whereas the traditional outside perspective of South Africa sees the race issue as being essentially that of a binary black/white divide; the tension between those South Africans of Anglo-Saxon lineage and Afrikaners is presented as a potential vehicle for delivering Cronje. This backdrop is particularly pertinent to the Free State in which Cronje grew up.

As Professor Bruce Murray argues in the film, the rise of the Afrikans middle class during the isolation years saw them compete with the English speakers for places in cricket teams at all levels. Wessels, Cronje and De Villiers had risen to the top and entered the team and, once Wessels had retired, it did not seem too unusual to build the team and craft the new generation around an Afrikaner, Cronje. While, of course, there had been a history of Afrikaner representation at national team level, they had never appeared so numerous as during the period of South Africa’s re-emergence from that two decade-long hiatus. Players of the calibre of JJ Kotze, Peter Heine and Peter van der Merwe had all been prominent during different periods prior to isolation, as had Vincent van der Bijl during the painful ostracisation which followed. Maybe, given the fact that Wessells had played three years of Test cricket for Australia between 1982 and 1985, the notion of an Afrikaner putsch of the team after 1992 is one which is a little far-fetched. However, it is symbolic that it should be an Afrikaner, Cronje, who would share the stage with his country’s new president in early 1996 as South Africa had beaten England in the one day series. Mandela, sporting a green Proteas cap, as he had done when presenting Francois Pienaar with the Rugby World Cup a year earlier, complemented Captain Hansie on his exemplary leadership. Cronje, too, delivered his own eulogy to the iconic president in the evening sunshine. Each man, it seemed, was emblematic of this new South Africa.

If Cronje’s family and his Dutch roots were important in forging his competitive spirit and leadership philosophy, his education at the prestigious Grey College was of equally great value in giving that nascent talent a clear direction. The college was originally founded by the then Governor of the Cape, Sir George Grey. Clues as to the formative influence that this would have on Cronje can be gleaned from the bilingual – Afrikaans and English – Grey College website. The college, it says, has “served Bloemfontein, The Free State, South Africa and the world over the past 150 years” before going on to add a touch of obligatory 21st century management speak with its vision of being relevant in a “global village”. While a student there, Cronje was captain of the rugby and cricket teams and its current headmaster, Johan Volsteedt, recalls the embryonic leader with affection. In terms of its influence on outlook and bearing, whereas we can hark back and see Winchester as being synonymous with Jardine, we can also now associate Grey College with Cronje.

From the secure foundations of his formative influences: family, heritage, faith and education it may appear impossible to fathom what would make Cronje self-destruct. From being the poster boy of a new nation to utter vilification is, to put it mildly, an astonishing regression. It is, however, a journey that Cronje contrived to make. In forging a new and truly unified South Africa, the game’s administrators took it upon themselves to address age old inequalities via the implementation of a quota policy. In doing so, Yule and Oborne argue, they sowed the seeds of Cronje’s dissatisfaction with the South African captaincy. For while he must have recognised the need to address the vile legacy of Apartheid, he was vehemently opposed to what he considered a policy of window dressing which would weaken his team. Implemented just after a disjointed West Indies had been destroyed 5-0 in South Africa, and 8 years on from re-admittance to the international stage, Cronje’s team featured just two non-white players. From the end of that series the South African board insisted that a minimum of 4 “coloured” players should be included in each starting XI, with a total of 7 to be selected for each touring party.

It is clear from the interviews with Ali Bacher and Bob Woolmer that Cronje was so bemused by the crafting of the policy that he considered quitting his post. Seeking solace in the counsel of his old headmaster, Johan Volsteedt, Cronje resigned himself to continuing his work as captain. He did not remain as leader without airing his concerns on national television, though, arguing that no player should be granted selection under what he termed “special” circumstances. It is without doubt that Cronje was troubled by the policy; not, perhaps, on racial grounds, but because he could not countenance the weakening of “his” team. This was a nation, let us not forget, that on re-admittance had come within a game of the World Cup Final in Australia in March 1992 without having played a single Test match.

Since their return South Africa had been the one team to consistently compete with Australia, having enjoyed several battles royal with the new world power from down under. Now, in Cronje’s eyes, this seemed under threat. Both Cronje and Woolmer argued that the emphasis should have been on youth development and the creation of international class players from all backgrounds. Bob Woolmer, interviewed just weeks ahead of his death in 2007, argued, somewhat tangentially, that neither Australia and New Zealand were making strides with the inclusion of Aboriginal and Maori players. As Cronje’s power within the South African power structure had grown, so those that did not share his vision became jettisoned. Woolmer, so great an admirer of Cronje’s that he referred to him as “the greatest leader I ever worked with”, was even side-lined himself. Within the South African dressing room the smooth running of the team required the imprimatur of the captain and not that of the coach. It is against this background, that of a newly formed team, truly competitive and pulling in the direction of its leader that the board – with very noble intentions – created conflict. In this context Cronje can be seen as a latter day Ian Chappell; the team’s leader and not the establishment’s captain. Moreover, at that juncture the edifice of the Cronje years fell. Having had selection policies foisted on him and with board interference into what he felt was his domain, Oborne and Yule advance the thesis that Cronje went down the route of accepting bookmakers’ hard cash. As Stephen Brenkley argued in The Independent:

“The dramatic implication is that Cronje, more or less forced to take part in a more sympathetic selection policy and one that truly embraced the new South Africa as the rainbow nation, was virtually saying: “If you don’t care if we win, then neither do I”

The documentary covers the actual match fixing scandal itself, giving particular focus to the 1998-99 Leather Jacket Test with England, in which both Cronje and Hussein agreed to forfeit their first innings in order to set up a final day spectacle. What was initially trumpeted as a fantastic advert for imaginative captaincy and attacking cricket now leaves a hollow feeling. The feeling gets worse when the bookmaker at the heart of the scandal, Marlon Aronstam, is interviewed. A gurning, grimacing figure, Aronstam reveals just how easy it was to convert Cronje to his thinking. In his testimony to the King Commission on match fixing, Cronje admits that he was persuaded by Aronstam’s criticism of his defensive leadership. A final day jamboree, the bookie felt, would rejuvenate Cronje’s reputation for cautious captaincy and tactics. England, as we all know, narrowly won the game and Cronje later received his own remuneration over a breakfast meeting with Aronstam, together with a leather jacket, a gift for his wife. It is difficult to know who is more deserving of contempt: Aronstam for his combination of arrogance and seediness, or Cronje for his betrayal of trust.

We will never know if the film-makers’ were correct in asserting that Cronje simply threw in the towel due to what he considered the South African board’s interference in selection policies. Although he had taken money from the Indian bookmaker, MK Gupta, from as early as 1996, it is, however, incontrovertible that Cronje’s acceptance of bribes increased after Cricket South Africa’s introduction of the quota system. Marlon Aronstam had wanted to reveal to his associates that cricket was not the “clean” sport that they thought it was. According to him, a simple phone call to the captain of South Africa was enough to prove otherwise. There is an even more sinister undertone to the matter, though. The two players Cronje attempted to corral into his plans on the India tour in 2000 were both non-whites, Hershelle Gibbs and Henry Williams. Their captain sensing in them, perhaps, an insecurity and vulnerability that could best be assuaged by them gaining their leader’s favour. For Oborne and Yule this is one of the most distasteful chapters in the whole episode. The rank hypocrisy of the devout Christian, Cronje, intoning to the nation’s youth in his television message “Be fair in sport, be fair in life, don’t do crime” may seem risible now. There were those, however, for whom the devout preachiness of the South African team had begun to grate even before the scandal broke. Michael Atherton, in his autobiography, has gone on record as finding their piety and unctuousness particularly distasteful and jarring.

Like Cronje himself, the quota system continues to divide opinion. Given as toxic a legacy as Apartheid, the South African governing body were obliged to do something to ensure that all cricketers, irrespective of background, had the means to ensure representation. In such unique circumstances whatever measures they adopted would have perhaps have been thought controversial. In 2008, Gerald Majola, the Cricket South Africa chief executive claimed that there was no definitive timeframe to bring it to a close, noting “Nobody at this stage can forecast when this will take place, as the massive disparities in facilities alone still remain a legacy of the past”.

Not Cricket: The Captain and The Bookmaker advances a fascinating argument for the reasons behind Cronje’s fall. Given Peter Oborne’s most recent tirade against what he describes as South African “mercenaries” in English cricket, counting among their number Tony Greig, Allan Lamb and now Kevin Pietersen, it is perhaps unsurprising that he should have pointed both barrels so squarely in the direction of Hansie Cronje’s already battered reputation. That said, as a documentary it successfully draws us into the dark world inhabited by that tragic, tormented and complex figure.

This is a tragic tale with so many dramatic elements. Both Cronje and Woolmer are no longer with us, leaving a mystique to the tale that will never be unearthed. The ultimate question – of why Cronje took the money – is, again, something which will remain a mystery. In the final interview before his death, Woolmer insisted that Cronje’s acceptance of bookmakers’ cash was money for old rope and that, in reality, very few favours were granted them and no games thrown. Put simply, Cronje had succumbed to the temptations of mammon and was lining his own pockets. Just as Bill Clinton embarked on his relationship with Monica Lewinsky because he could so, Woolmer and others argued, Cronje was accepting the brown paper envelopes because he could, too. Over a decade on from his death South Africa will be grateful indeed that they have moved on from the events of the Cronje years. Now the top team in international cricket, they will be keen to leave the memories of those days in the past. For better or worse, when the plane carrying Wessel Johannes Cronje crashed into the Outeniqua mountains on 1st June 2002, he left behind him a riddle that will never be solved.

Fantastic read… will have to watch the BBC4 now, for sure.

Comment by Quaggas | 12:00am BST 6 October 2012

Great article. Wish I could watch the doccie.

I remember as a fan, just wanting my team to win, Hansie was captain, my captain and could do no wrong. At the same time, I remember older people who hated the SA team and would literally support any other team but them, these people mostly still do.

For me, the main source of bitterness was that. It was sometimes hard to be a SA supporter (especially a non-white one,) you were surrounded by people who disliked the team yet you still had faith in this guy, his pious image of righteousness, the certainty in your heart that you may lose but this team and captain would never, ever give up without a fight. He was *the man*

And then the news broke in India, my uncle called us up just before school and told us to turn on the TV, he’d always said someone’s going to fall from grace soon so he was almost reveling in it. Now, I’m of Indian origin but that mattered little. Who were those (probably corrupt & overweight) Indian cops to say those horrid things?

He’d never do that, our Hansie, pure as the driven snow he was. He did do it though and it became more and more apparent after every passing hour, but that hope was still there. Hansie still denied it and for me, that meant it was still nothing more than lies. Then he said he did it and that was that.

I’m still a big Proteas fan and always will be but SA cricket has never recovered from that day. He shattered the image of the sport, he sold us out for a frakking leather jacket and a meagre handful of silver. I still remember people softening towards him in the later years, some even suggesting he be allowed back to do coaching, that pissed me off to no end. Forgive sure but even allowing him back onto a cricket field would have been too much for me I think. None of it to be in the end though.

Comment by nexxus | 12:00am BST 9 October 2012

I would have done it too if I was in his shoes. …..

Comment by Spooony | 12:00am BST 10 October 2012

Great read..Sad end..btw documentary is in u2be

Comment by doesitmatter | 12:00am BST 10 October 2012