Nightmare Down Under

Martin Chandler |

BACKGROUND

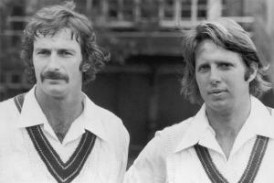

In 1972 in England a 23 year old Denis Lillee had taken 31 wickets at less than 18 runs each in his first full series. His opening partner for four of those games, the mercurial debutant Bob Massie, had taken 23 at the same cost. Despite these impressive contributions the series had however been drawn 2-2 and England, led by Ray Illingworth, had retained The Ashes that Illingworth’s last side had regained in Australia in 1970/71.

By the time cricket’s greatest rivals were ready to square up to each other again, in the Australian summer of 1974/75, Massie was finished. He had played just two more Test matches after that 1972 series and, his prodigious swing having deserted him, he had drifted out of the First Class game. For Denis Lillee there had been fitness problems in the Caribbean in early 1973 and, eventually, a diagnosis of a stress fracture in a lower vertebra and there was speculation that his bowling career was over.

In the series that they had played since 1972 the Australians had been struggling to find a settled pair of opening bowlers. They had discovered Max Walker, who had made a fine start to what was to prove a successful career, but he was strictly fast medium. At various times Alan Hurst, Tony Dell and Jeff Hammond as well as left armers Geoff Dymock and Gary Gilmour had been tried. None let Australia down but they had not even begun to suggest that they might be adequate replacements for Lillee and Massie. In addition a genuinely fast young bowler, Jeff Thomson, had made his debut against Pakistan in 1972. Desperate to play Thomson had decided not to inform the selectors that he had a broken bone in his foot and his match return of no wicket for 110 had seen him swiftly discarded.

After retaining the Ashes in 1972 England had lost in India the following winter but the next year, after losing a home series against West Indies, they had drawn a series in the Caribbean and the hammering that they gave India in the first part of the 1974 season created the impression that all was well with their batting. Against India the averages had been quite remarkable, David Lloyd achieving 260, Keith Fletcher 189 and John Edrich’s 101 making it a trio of English batsmen with a three figure average. With Mike Denness and Denis Amiss both averaging more than 90 it is hardly surprising that all five men were selected for Australia. Later in that 1974 summer those same English batsmen found runs harder to come by against Pakistan, who drew all three Tests in their series, but that did not dampen expectations and a confident 16 man party left England at the end of October. The average age of the party as a whole was 31, and of the batsmen 32. When, after the first Test, England called for batting reinforcements and Colin Cowdrey arrived, the average age of the batsmen rose to 34. The party came to be known in Australia as “Dad’s Army” or the “Old Contemptibles”.

FIRST TEST

In the run up to the first Test, which began at the ‘Gabba in Brisbane at the end of November, the tourists had done well and all of the batsmen had made runs. The itinerary meant that Lillee and his West Australian side had not been met but Thomson had played against them for Queensland, and while he had bowled quickly and economically had taken only two wickets and prevailing opinion seemed to be that he was not high in the selectors thoughts for the Test matches. As the tourists had set off so Lillee had played his first First Class match for more than 18 months and he was to play five state matches before the first Test. His remodelled action brought him 25 wickets at 28 runs each and, perhaps as importantly, he put in plenty of overs. It was no surprise when Lillee was named in the Australian twelve for the first Test – the appearance of Thomson’s name caused more of a stir.

Two days before the Test began two inches of rain had fallen in Brisbane and it was something of a surprise when the mud bath which the curator had been faced with after that was ready for a prompt start on the first day of the match. To the astonishment of all Ian Chappell, on winning the toss, chose to bat and with Australia at 219 for 6 at the close, and all out for 309 shortly after lunch on the second day, he must at times have wondered whether he had made the right decision.

Luckhurst and Amiss cannot have anticipated just what a reception they would get from Lillee and Thomson when the England reply began. Lillee was, probably, not quite as quick as he had been before his back injury but anything he had lost in speed was more than made up for with a degree of aggression that made him seem a completely different bowler from the one who had done so well in 1972. Thomson was, it was generally felt, even more hostile and the England batsmen faced a barrage of short pitch deliveries which, ultimately, none were able to deal with for very long. That England got to within 44 of the Australian first innings was due to a typical display of courage from John Edrich and a century from Tony Greig who was ably supported by the tail. Greig’s innings was by no means chanceless but he at least took the fight to the Australians in a way that England batsmen would seldom do over the course of the series.

In the Australian second innings they made a poor start but the middle order allowed Chappell to declare and leave England a target of 333, half the number of the beast, in just over a day. In fact Chappell only got about 10 minutes at the England openers that evening as the umpires, after warning Thomson about bowling too short, decided the light was unfit for play. Chappell was furious at what he saw as an attempt by the umpires to dictate how his bowlers should bowl. He need not, however, have been concerned. The next day England were bowled out cheaply to give Australia victory by 166 runs. Thomson had taken 6 for 46 in that second innings and nine in the match.

SECOND TEST

Both Amiss and Edrich had picked up hand injuries and Fletcher one to his elbow. Unwilling to bring a promising youngster over as cover the calls went out to 41 year old Colin Cowdrey who arrived in time to take his place in the side for the second Test at Perth. Remarkably he was not to be the oldest man in the England team – that distinction would fall to the 42 year old off spinning all rounder from Middlesex, Fred Titmus.

Chappell won the toss and he invited England to bat. To start with England coped admirably with Luckhurst and Lloyd seeing off Lillee and Thomson before Walker removed Luckhurst at 44. Cowdrey then came out to join Lloyd and they took the score to 99 before Lloyd was out for what was to be his highest score of the series, 49. Lloyd was the youngest of the batsman in the touring party but he was destined never to play Test cricket again after the tour. Lest it should ever be suggested otherwise however it must be stressed that he batted as bravely as anyone and, struggling himself in this match, made the selfless gesture when joined by Cowdrey of ensuring that while the veteran was getting used to conditions that he took Lillee and Thomson and left Cowdrey to deal with the rather less intimidating Max Walker.

Unfortunately for England the comparative comfort of 99 for 1 slipped to an all out total of 208 with only Alan Knott making a half century. Australia built up a first innings lead of 273 and while England’s second innings performance was rather better, only Fletcher of the front line batsmen failing to get a start, they struggled to overhaul the deficit and Australia were left with only 21 to score for victory which they did for the loss of just one wicket. It can have been no comfort to the England management to reflect on the fact that their two over 40s, Titmus having top scored with 61 in the second innings, scored more than a quarter of England’s runs in the match.

THIRD TEST

The third Test was the Boxing Day match at Melbourne and England brought back Amiss and Edrich for Fletcher and Luckhurst. Chappell won the toss for the third time and did not hesitate to insert England again. The result was an all out total of 242 with brave contributions of 35 and 49 respectively from Cowdrey and Edrich at the top of the order. A typically unorthodox half century at the end from Alan Knott was the only other significant contribution. England could also complain of poor luck given that Edrich was given out caught behind when the Australians had appealed for a stumping, and later Greig was run out for 28 when television replays suggested he had made his ground with a couple of inches to spare. Greig did not take the decision with good grace and in what was already becoming a difficult series further ill feeling was generated.

Perhaps inspired by the injustice of their own innings the English bowlers now rose to the occasion and, albeit only by a single run, they secured a first innings lead. In the England second innings Amiss and Lloyd had clearly decided that attack was the best form of defence and with reckless abandon they rattled up an opening partnership of 115 at better than a run a minute before off spinner Ashley Mallett removed Lloyd. There was then a collapse and of the remaining batsman only Greig, who followed the lead of Amiss and Lloyd, made a significant contribution although Bob Willis propped and copped for well over an hour and a half while 50 precious runs were added for the ninth wicket.

The final day of the Test promised to be a fascinating one with Australia, 4 for no wicket at the close, requiring 246 to win. They finished that final day with 8 wickets down for 238 and the game was therefore drawn. There was much criticism of Denness’s captaincy as he refused to attack at the end and, from the point at which Walker and Lillee came together at 208 for 7, defensive fields were set. It was a disappointing end to a match which, otherwise, England emerged from with a degree of credit.

FOURTH TEST

England had to avoid defeat in the fourth Test if they were to retain any hope of retaining The Ashes. After just 65 runs in 6 innings and the criticism of his captaincy in the previous Test Denness decided to stand down and Edrich, at 37, took charge of his country for the first time. Denness was replaced by Fletcher, who looked more uncomfortable than most against Lillee and Thomson. Fletcher had been dropped from the third Test after scoring just 40 runs in 4 innings, and his selection hardly gave rise to any confidence that the batting had been strengthened.

Chappell won the toss for the fourth time and this time chose to bat and, without performing particularly well, the Australians totalled 405 in their first innings. England struggled again in reply reaching 123 for 5 before Edrich was joined by Knott. Edrich’s captain’s knock of 50 and Knott’s 82 were the only substantial contributions to a first innings effort that conceded a lead of 110. Australia batted comfortably on to leave England with just over a day to score 400 for victory.

Not for the first time Amiss and Lloyd put bat to ball and managed to put on 68 for the first wicket but they never inspired confidence. Edrich came in after the openers and batted for more than three and a half hours to carry his bat through the rest of the innings for 33. Edrich apart only Greig, who top scored with 54, and Willis who kept the bowlers out for almost an hour and a half for his 12, gave any impression that they might hold out. It was a tame defeat in the end and an ill tempered match Greig, rather ironically, being warned by the umpires for persistent short pitched bowling at Lillee. Both men took umbrage for differing reasons and no doubt most of Greig?s colleagues were concerned at the manner in which he chose to rile Lillee.

FIFTH TEST

England were in a state of some disarray as the fifth Test loomed. An injury to Edrich, two broken ribs courtesy of a Lillee bouncer at Sydney, meant that Denness had to take up the reins again. For once England won the toss, and perhaps not surprisingly invited Australia to bat. With the home side sinking to 84 for 5 it seemed that the pressure being off had worked in England’s favour. For Australia however the rot stopped there and Doug Walters and the lower order took the home side to the relative comfort of 304 which, with the first day having been lost to rain, was assumed would be a total to guarantee a draw. In the event England’s batting was at its most feeble as only the men who had hitherto been the weakest links, Denness and Fletcher, in scoring 51 and 40 respectively, showed any resistance. Cowdrey also showed the right attitude with a stubborn 26 in an hour and a half but apart from those three the innings subsided and England were 172 all out. Australia finally declared 403 in front leaving England, once again, with just over a day to survive.

Without an intervention from the weather, which never came, no one expected England to survive on the final day and they duly capitulated again. Thomson did not bowl in the second innings as a result of a shoulder injury but three wickets from Lillee and one from Walker blew away the England top order for 33. Free of the worry of facing his nemesis,Thomson, Fletcher made an attractive 63 and he and Knott batted through the whole of the morning session of the final day to give England a little hope and some respectability, but the result was a formality once Fletcher was trapped LBW by Lillee. At least the lower order, and particularly Willis again, managed to remain at the crease long enough for Knott to complete a deserved first Test century against Australia. The eventual all out total of 241 did however leave England 163 runs short and there were doubtless some Australians who regretted their caution in the latter stages of the third Test and the fact that they were not 5-0 up.

SIXTH TEST

Thomson had taken 33 wickets at less than 18 runs apiece and Lillee had at this stage taken 24 at 23. It is often forgotten that off spinner Ashley Mallett ended the series with 17 wickets at less than 20 and that Max Walker took 23 at 29. Despite the excellence of Australia’s support bowlers that Lillee and Thomson were the difference between the two teams was vividly illustrated by the events of this sixth and final Test for which Thomson was unavailable because of his injury. From the 1990?s on it almost became the norm that Australia would lose the dead rubber of an Ashes series but in 1975 the expectation was that they would go on to wrap up a 5-0 victory.

Australia won the toss and chose to bat at the MCG which proved to be a mistake. Lancashire’s Peter Lever, dropped after a wicketless first Test, now put in the performance of his life as he removed four of the Australian top order to leave the innings in ruins at 23 for 4. Ian Chappell and the middle order showed a little more resolve but Australia were still all out for 152, the lowest total by either side in the series.

England’s reply began unpromisingly as Lillee removed Amiss for his third successive duck in the opening over, but after just six overs Lillee was withdrawn from the attack and limped off the field suffering from a bruised heel. He did not bowl again in the match and England proceeded to show why they had, for most, been made favourites before the series began. Edrich and Greig both made half centuries but the main honours went to the much maligned pairing of Denness and Fletcher who both recorded big centuries, 188 and 146 respectively, as England put the match out of sight in totalling 529. The Australian upper order performed much better second time round, and for a time it looked like a draw could be salvaged, but from 289 for 3 the home side subsided to 373 all out to give England a consolation victory by an innings and 4 runs.

THE AFTERMATH

England and Australia would meet again within months when a series of four Test matches was played following Australia’s defeat by West Indies in the inaugural World Cup final. Tony Greig had said at the end of the tour “We’ll thrash the pants off you blokes next time” and he had replaced Denness as England Captain by the time the second Test of the series began. With England struggling on under Denness the first Test was won by Australia by an innings but that was the only definite result in a series from which England ultimately emerged with their pride intact, mainly thanks to the efforts of Greig, Knott and, plucked from county obscurity, “the bank clerk who went to war”, David Steele. After that it was Packer and the chaos that came with World Series Cricket, followed by the emergence of Ian Botham, that caused the balance of power between the two countries to shift once again.

SOME REFLECTIONS

The benefit of hindsight allows a long look to be taken at England’s performance in 1974/75 and to make informed judgments as to where mistakes were made. The glaring problem was the batting. One of the difficulties the selectors had was that the leading England qualified batsman of the 1974 season, Geoff Boycott, had ruled himself out. Judging by his performances against the West Indies pace battery in 1980 and 1980/81 Boycott would have undoubtedly given stability to the fragile batting lineup.

Another issue is whether Cowdrey was a wise choice as replacement. The veteran did not let the selectors down but made no substantial contributions. That the selectors did not wish to pitch a youngster into the fray is understandable, but it is a great shame that the Greig influenced selection of David Steele was not made a few months earlier. That apart the selectors were in a difficult position. Roy Virgin of Northamptonshire had had a superb season in 1974 but had never been selected at the highest level and in any event was 35. Others who rode high in the averages were Mike Smith of Middlesex, John Jameson of Warwickshire and John Hampshire of Yorkshire, but they were all in their thirties too. Of the younger batsmen the previously untried pair of Sussex’s Peter Graves and Gloucestershire’s Roger Knight were both 28 but, despite reasonable seasons, had been 25th and 27th respectively in the averages. That the batsmen selected were the wrong combination is clearly the case but in fairness to the selectors their options were limited.

As far as the bowling was concerned while history has blamed England?s batting for her abject defeat, the omission of pace bowler John Snow from the party cannot have helped. Snow could be an abrasive character and the fact that the Tour Manager and Chairman of Selectors, Alec Bedser, had had enough of him is often cited as the reason for that omission. That Bedser did not always approve of the way in which Snow conducted himself, both on and off the field, is beyond doubt, but it is equally clear that he rated him highly as a bowler and Snow himself has conceded that the main factor behind his failure to make the party was likely to have been some highly critical remarks about the selectors that appeared in the press in his name. Had Snow, England’s spearhead in both the 1970/71 and 72 series, been selected he would have ensured that England fought fire with fire. It is true that Snow was 33 when the series began, but he had taken 76 wickets at 19 apiece in the 1974 season and, his cause championed by his county captain Greig, he returned to the Test side in 1975 and 1976 and took another 26 good Australian and West Indian wickets at less than 30 runs each before, a couple of months short of his 35th birthday, his Test career finally ended.

What of the captaincy? Denness’s Test record suggests a batsman just short of real international class, but his career average of fractionally under 40 is much better than, for example, Mike Brearley, and he had captained England well in the Caribbean in 1973/74. The easy victory over India in the first half of the 1974 summer did, perhaps, cause too many to overlook his failure to inspire his team to victory over an unexpectedly effective Pakistani side later in the summer. Looking back the elevation of the combative Greig to the captaincy really should have occurred before the Ashes party left and not await the home defeat the following summer that finally caused the selectors to lose patience with Denness. Had Greig been captain and, accordingly, on the selection committee, then no doubt Snow would have toured rather than sit out the series in the pressbox. As for Steele he may even have made the original party but if not would surely, with Greig fighting his corner, have joined it after the first Test. Such speculation is one of the greatest pleasures of cricket talk and, for what its worth, I believe Ian Chappell and company were fortunate in 1974/75. If they had faced an England side led by Tony Greig rather than Mike Denness then, as the outcome of the 1975 series demonstrated, the history of the Ashes might be different.

Striking, by today\\\\\\\’s standards (this northern summer\\\\\\\’s season in the UK aside) the degree to which ball dominated bat. Not surprising with Lillee and a pre-injury Thompson, but still interesting in these days of \\\\\\\’five day pitches\\\\\\\’ and armoured tail-enders hanging around.

Comment by Matt79 | 12:00am BST 8 September 2010

A good read – thanks for taking the time to write it.

It was the my first Ashes series in Australia, so I remember a fair bit of it. As you say, none of us had heard of Thomson, although we alredy knew about Lillee. Had the series been played 12 months earlier, we’d have faced an attack of Walker, Dymock and Hammond, which would probably have produced a very different result: certainly a more equal contest anyway. My take on selections at the time was that Luckhurst shouldn’t have toured – he’d been hopeless against Lillee in 1972 – and that obviously Snow should have.

That being said, I think that we’d have been hammered whoever we took: a view that was supported when WI lost 5-1 over there 12 months later.

Comment by wpdavid | 12:00am BST 8 September 2010

Another worthy addition to an already impressive oeuvre. 🙂

Particularly enjoyed the line [I]”a target of 333, half the number of the beast”[/I]; well turned and, considering the attack, very apt.

Comment by BoyBrumby | 12:00am BST 8 September 2010

Top read that.

This year no doubt will be dubbed “Nightmare Revisited”. Johnson-Bollinger might not have the same ring as Lillee-Thomson now, but wait til January.

:ph34r:

Comment by Burgey | 12:00am BST 8 September 2010