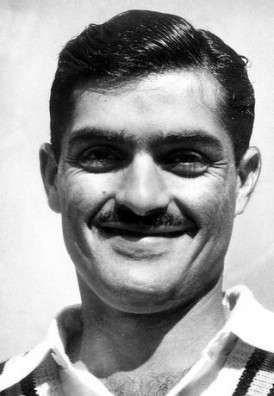

Nari Contractor – A Grand Old Man of Indian Cricket

Martin Chandler |

He should really have been born in Mumbai (or rather Bombay as it then was), but Nari Contractor’s train driver uncle realised that one of his passengers on 7 March 1934, Nari’s mother, was in some difficulty, so he persuaded her to disembark with him at Godhra when his duties ended. The intention was that, fully recovered, he would then get her back to Mumbai the next day, but Nari wouldn’t wait and was born the same day.

The serendipitous outcome of this was that Contractor was qualified by birth to play for Gujarat, and at a time when the Bombay side was extremely powerful he was able to gain selection for Gujarat for their game against Baroda in November 1952. Contractor made the headlines after the game as he became only the second man, after Australian Arthur Morris, to score a century in each innings on First Class debut. Six others have managed to emulate Morris and Contractor since, although looking at the bowlers opposing each of the eight it is difficult to come to a conclusion other than that Contractor’s feat is the most impressive.

In the following three years Contractor’s run scoring feats were relatively modest. He generally batted at three and managed just one more century after his remarkable debut. He had not been forgotten however and when Pankaj Roy was dropped after a failure in the first Test of the first ever series between India and New Zealand Contractor was one of two additional batsman brought in for the second Test, the other being the 17 year old Vijay Mehra. Neither achieved much in that Test, but both were retained for the third and, Vinoo Mankad having to drop out, the pair opened together. It was Contractor who, with 62, took his opportunity and was retained for the fourth Test when, Mankad having returned to partner him, he managed another half century.

At this point it might have been expected that Contractor had established himself, at least for while. In fact Roy had managed to get a late call up for the fourth Test and, batting at three, scored exactly 100. For the final Test he displaced Contractor at the top of the order and Roy and Mankad posted their remarkable opening stand of 413. Scheduled to come in at seven Contractor never even got to the crease, and he didn’t get another cap until the third and final Test of the 1956/57 series against Australia after Mankad decided he no longer wished to open the batting. In a low scoring defeat Contractor opened with Roy and scored 20 and 22. Only Vijay Manjrekar scored more runs for the Indians.

West Indies visited India in 1958/59 and won 3-0 with two Tests drawn. The key to their success was the fearsome pace bowling of Roy Gilchrist and Wes Hall, who took 56 wickets between them. It was a difficult series for Contractor. He scored runs in both innings of the second Test but failed in the first and third and in the fourth Test the selectors asked AK Sengupta to open with Roy with Contractor dropping to four. In the event Sengupta scored just a single, whilst Contractor compiled a typically stubborn 22 and Contractor and Roy were reunited at the top of the order in the second innings. In the final Test, India’s best performance of the series, Contractor made some progress towards cementing his position in the side with a fine 92.

So what kind of batsman was Contractor? There were, to say the least, divergent views. On a positive note is the description of the veteran Indian writer Kishin Wadhwany; No left-handed Indian batsman was more accomplished than Nari Contractor in the range of onside strokes. He was a master craftsman, a great artist. With a precise and subtle turn of wrist and occasional force of strength, he could alter the direction of the ball beyond the reach of fieldsmen, for a destined boundary. He had the ability to delay his shot as late as one could conceive. He had a computer-mind for strokes between the area of fine leg and mid wicket. ….. gifted as he was in stroke production on the onside region, Contractor was, in no way, devoid of shots on the off side or of front foot strokes. He could lean forward in his own leisurely manner to drive, which he followed by referring to one drawback; his grip and the movement of his feet, however, prevented him from cutting.

Rather less complimentary is the pen portrait that appeared in a UK brochure for India’s 1959 tour of England that was edited by Gordon Ross. It is not clear where the material comes from, and if Ross wrote it whether he had ever seen Contractor bat, but he describes Contractor as being pitchforked into the opening pair through sheer necessity before adding that; the responsibility of opening the innings has curtailed his stroke-play. He now holds the bat almost at the bottom of the handle and hence cannot drive either correctly or forcefully and collects his runs mainly with deflections. Weak against the ball that leaves him, Contractor frequently uses his pads as a second line of defence.

The 1959 Indians did not have a happy tour, losing all five Tests and winning only six of their 33 First Class matches. Contractor did not begin the tour well, in the run up to the first Test scoring just a single half century, albeit he managed that against the full strength of reigning County Champions, Surrey. In the first Test itself England, fresh from their disheartening experience in Australia the previous winter and including three debutants, batted first and piled up 422. It was enough to win by an innings. In a dogged start to the Indian first innings Contractor scored 15 in 104 minutes. He was caught at slip without scoring in the second innings.

At Lord’s for the second Test India batted first and, on a fast wicket, a short delivery from Brian Statham soon leapt from the notorious ‘Lord’s ridge’ and struck Contractor on the chest, fracturing a couple of ribs. The effects of the injury were to keep Contractor out of the game for almost a month. On the day he was struggling to breathe, but skipper for the match and opening partner Roy was desperately keen for him to remain if possible so he did. He was eventually seventh out for a battling 81. The famous Australian all-rounder and by then writer Keith Miller considered the innings warranted a Victoria Cross.

The Indians were all out for 168, and whilst they restricted England to 226 England still ran out comfortable winners. In the Indian second innings Contractor was in plaster and in pain and his movement was too restricted for him to take his place at the top of the order. When India were in trouble again Roy, keen to set some sort of target, asked Contractor to go in once more. Always a great team man Contractor agreed and went in at the fall of the sixth wicket, and was unbeaten on 11 when the last man was dismissed with the score on 165.

After missing the third Test with his rib injury Contractor came back into the side for the match against Middlesex immediately before the fourth Test. He managed 55 in the first innings to show he was fully fit again and the Test, although lost by 171 runs, was India’s best performance of the series. The game did not begin well as England piled up 490, and India’s reply was only 208. Contractor made 23 in an hour before, in attempting to hook Derbyshire paceman Harold Rhodes, he gloved the ball to wicketkeeper Roy Swetman. Unusually for the times England chose not to enforce the follow on and India began their second innings in pursuit of 548 for victory. Contractor spent the greater part of three hours over 56, Abbas Ali Baig scored a century and Contractor’s fellow Parsi Polly Umrigar did so as well, and in totalling 376 India could at least hold their heads up.

The improvement did not last at the Oval, India capitulating for 140 and 194 to lose by an innings once more. Contractor did his best but became completely strokeless as he took as long as 199 minutes to score 22. Such was his mindset that when Ted Dexter chose to bowl him a medium paced full toss he was so surprised that he could do nothing more than tamely drive the ball into the hands of Ray Illingworth at cover. In the second innings Contractor contributed 25.

After recovering from his rib injury Contractor’s form certainly improved. He managed five half centuries altogether and eventually, at the Hastings festival in September, he recorded his one century of the tour. He was third in the Indian Test averages with the highest aggregate, and sixth on the tour as a whole. Wisden’s verdict on him, whilst praising his courage, had some echoes of the Ross brochure; on the whole he failed to impress the public that he was more than an ordinary plodder …………. he will be remembered for his leg side glances, but his cross bat driving when trying to push along the rate of scoring revealed his limitations.

In 1959/60 Australia, just three years after their previous visit, came back to India for a full five Test series. With the bat this series was undoubtedly Contractor’s best. He could not prevent Australia taking the series 2-1, but with 438 runs at 43.80 he batted with great consistency. Only once did he fail to get to 24, and that was in the first innings of the fourth Test when illness forced him to drop down the order to number four in the first innings. In the third Test Contractor recorded what was to remain his only Test century, 108. The Australian side was a relatively young one, with no Keith Miller and Ray Lindwall past his prime, but two younger world class bowlers, Alan Davidson and Richie Benaud both had magnificent series. In the final Test Contractor’s occasional right arm medium pace claimed its only ever wicket, the prize scalp of Neil Harvey.

After the Australian series India’s captain, Gulabrai Ramchand, retired from Test cricket and, for the visit of Pakistan in 1960/61 Contractor became, at 26, India’s thirteenth Test captain. The series was a complete contrast to the one going on at the same time between Australia and West Indies. All five Tests were drawn, and indeed there was no winner in any of the fifteen First Class matches on the tour. To be fair to Contractor there was not a great deal he could do about it. He lost the toss in the first four matches and, on choosing to bat, Pakistan then batted first and killed the game.

The final Test was not played at a significantly greater tempo but, without a last wicket partnership of 38 after being asked to follow on, Contractor and India would have broken the deadlock . With the bat Contractor enhanced his reputation by scoring 319 runs at 53.16 with half centuries in the first, fourth and fifth Tests. The innings were very much ‘in character’ the highest of them, 92 in the final Tests, taking up all but six hours.

In the following Indian summer two Test series were arranged. The first was a full tour by England, the first time the MCC had sent a team for a decade, to be followed by a series in the Caribbean. England were not at full strength, Colin Cowdrey, Statham and Trueman all being missing, but there were still plenty of high quality players in the side that Ted Dexter led. Contractor was Indian captain once again, and although there were many still happy to criticise him for an over-cautious approach he won the series 2-0.

The first three matches were drawn, the first in circumstances where Contractor declined to chase a target of 294 at 72 runs per hour. In the modern game no captain would be so generous although at the time four runs an over was considered fast scoring. In any event Contractor and India were clearly risk averse and made no attempt to chase the target down. India’s two wins were thoroughly merited however, all-rounders Chandu Borde and Salim Durani playing leading roles. For Contractor there was an innings of 86 in the first innings of the final Test, but little else and he averaged just 22.50 with as many as eight of his teammates above that mark. Nonetheless Contractor had the satisfaction of being the first Indian captain to win a series against England and, something he has doubtless shown regularly to the naysayers over the years, the report on the series in Wisden described his captaincy as imaginative.

The taste of victory did not, sadly, linger too long in Indian mouths. In the Caribbean they suffered another 5-0 reverse, on a tour that was marred by the dreadful injury that Contractor suffered in the tour match against Barbados. In the lead up to the first Test Contractor scored runs against Trinidad, but then just 10 and 6 in the Test. The pattern continued as he scored a century against Jamaica, but only 1 and 9 in the Test.

Moving on to Barbados the Indians were faced with Charlie Griffith. He had made his Test debut against England a couple of years previously but had not been selected for either of the first two Tests of the series so the Indians had not seen him before. The Griffith action had already attracted adverse comment however, and at a function before the Barbados match even West Indies skipper Frank Worrell warned the Indian batsmen about him.

The dreadful injury occurred in the third over of the Indian innings, and the first after lunch. Griffith was bowling extremely quickly. Ironically had the Bajan skipper, Conrad Hunte, not been such an honourable man the fateful delivery might not have been faced by Contractor at all. He had played the previous delivery straight into the hands of Hunte at short leg, but Hunte knew he had taken the ball on the half volley so there was no appeal.

In simple terms what followed was that Contractor was struck on the temple, fracturing his skull. It was touch and go for a time, but the skill of a specialist neuro-surgeon who was hurriedly flown over from Trinidad ensured Contractor would survive. As to exactly what occurred with no television pictures we need to look at the accounts of the participants. There is no unanimity. Griffith’s famous partner, Wes Hall, wrote later; He (Contractor) got behind a ball from Charlie, intending to push it towards short leg, completely misjudged the kick, bent back from the waist in a desperate last second bid to avoid it and was hit just above the right ear. Hall added; It had not been a vicious ball, never rising above the height of the stumps and he concluded Griffith was in absolutely no way to blame. In his own autobiography Griffith described the delivery as being bail height, but given that he also wrote that he had already dismissed Vijay Manjrekar at this point (he hadn’t) his recollection is undoubtedly unreliable.

The height of the delivery is where the controversy arises. According to Garry Sobers he had to tell Griffith not to appeal for lbw. Griffith himself suggested it was wicketkeeper David Allan who was ready to appeal. In 2002 Sobers wrote that Contractor ducked into a ball that didn’t get up. The Indians disagreed. Farokh Engineer is adamant the delivery was a bouncer. The man who replaced Contractor as skipper, Pataudi Jnr, acknowledged that his captain ducked into the ball, but wrote that the ball started at neck height, and Contractor does not dispute that he made a desperate attempt to jerk his head backwards and out of the way when he realised how much difficulty he was in. Erapelli Prasanna was not so dogmatic, writing that he didn’t believe the delivery was a bouncer, but he certainly didn’t suggest that he agreed with Hall’s account.

According to Wisden, certainly a neutral reporter, Contractor did not duck into the ball. He got behind it to play at it. He probably wanted to fend it away towards short-leg, but could not judge the height to which it would fly, bent back from the waist in a desperate, last second attempt to avoid it and was hit just above the right ear. Contractor himself has, in a number of interviews, always maintained that the delivery was a bouncer and that the suggestion he ducked into the ball is nonsense. The Indian writer Dicky Rutnager, watching from the press box, was clear that Contractor had got into line.

In many ways exactly what happened matters little but, given that all those quoted were doubtless being honest in their recollections, it is interesting to see the different perspectives put on the delivery by those who saw what happened all, of course, from different positions and not all of whom expressed their views at the time.

Having been struck with such a sickening thud immediately afterwards Contractor was dismissive of those who ran to his assistance, and he shaped as if he intended to bat on. A slightly delayed outpouring of blood from the ear and nose put a stop to that idea, and he was quickly helped from the field and after a brief stay in the pavilion was rushed to hospital. There were two operations, one by a local surgeon just to keep Contractor alive long enough for the Trinidadian specialist to arrive and carry out the surgery that saved the Indian captain’s life, with the assistance of blood from, amongst others, Worrell, Umrigar and Borde.

After his stay in hospital in Barbados Contractor went to a New York clinic before travelling home and coming under the care of a leading neuro-surgeon in Tamil Nadu. It was back in India that a steel plate was inserted into his skull, something which he has from time to time used to cause consternation amongst airport security staff.

A few months later despite his still suffering from poor vision and being somewhat unsteady on his feet, Contractor’s specialist recommended he restart his cricket career. This advice took Contractor by surprise, but he went to the nets and, as he had been told would be the case, his eye, reflexes and technique soon returned. He was ably assisted by the West Indian quick bowler Charlie Stayers. At the time the Indian Board had employed a selection of Caribbean pace men in an attempt to improve batting standards against fast bowling and the West Zone had been allocated Stayers who was happy to bowl fast and straight to Contractor whilst at the same time not, initially anyway, dropping anything at all short.

Ten months after that fateful day in Bridgetown Contractor resumed his First Class career in a charity match in Nagpur and scored 37 against an attack that included the West Indian Chester Watson. The following season, that of 1963/64, Contractor scored a century for West Zone in the semi-final of the Duleep Trophy and he scored four more before, in 1970/71, he finally retired. The Test selectors never came calling again however. They clearly did not have the same confidence in Contractor’s surgeon’s handiwork as the man himself had, and at one point asked one of his predecessors as India’s captain, Ghulam Ahmed, to speak to Contractor’s wife in an attempt to dissuade him from playing on.

Whether at any point Contractor’s form might have justified a recall is a tricky one. He had a poor season in 1966/67, so although his experience of English conditions would have been useful he was not selected in 1967. A couple of years later when he did enjoy a fine summer, averaging over 50, he might have got a recall against New Zealand but the selectors preferred a young Chetan Chauhan to open the batting with Syed Abid Ali. In an interview in 2014 Contractor told writer Clayton Murzello that not getting another Indian cap after his injury was his only regret in life, so the omission is clearly something he felt strongly about and, 85 and living in Mumbai, he doubtless still does.

Leave a comment