Mike Procter – A Swashbuckling Cricketer

Martin Chandler |

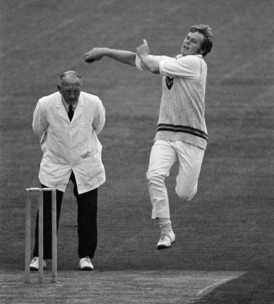

Even now, forty years on, I still have to blink a few times and watch several deliveries, preferably in slow motion, before I can see that Mike Procter did not bowl off the wrong foot. The barrel chested South African, sprinting hard with that look of grim determination on his face, was a whirl of arms and legs before he released the ball. The pace was not generated by any body swing, but by the long run and the heave of the right shoulder. In addition Procter delivered the ball very early, so that unusually for a fast bowler more strain was placed on the back foot than the front, and it was that, and the chest on delivery, that gave the impression he was even more unconventional than he actually was.

Interestingly the man himself grew up thinking his action was entirely normal. It wasn’t until Procter was sat in a cinema with his team mates after making his Test debut and saw himself on a newsreel that he realised what all the fuss was about.

Something else that always struck me as a youngster was just how fast Procter looked. He was a thrilling sight at full tilt and appeared to me to be the quickest I had seen, but I wonder now if that was all part of the illusion, because whilst Procter’s contemporaries all recognise that he was quick, none that I am aware of ever rated him as the ultimate speed machine. Certainly his sometime Gloucestershire teammate, David Green, felt he was a step down in pace from Wes Hall, and indeed the youthful Fred Trueman.

No one else bowled quite like Mike Procter though, which is perhaps part of the reason why he tends to be remembered as a bowling all-rounder. The stunning bowling figures that he achieved in his sadly truncated Test career reinforce that message, but in truth he was just as good a batsman and indeed, in his own view, that was his stronger suit. He might have been just a little impetuous at times, but was succinctly summed up by Green who described him as an attacking strokemaker of the highest quality, the greatest glory of his batting being his driving in the arc between cover point and the bowler, in which area I have never seen the ball hit so consistently hard.

Procter’s own views were doubtless influenced by his early experiences. As a twelve year old he hit five consecutive centuries, finishing that run with an unbeaten 210 against a representative Under 13 side from Transvaal. His initial selection for a South African Schools side was as a specialist batsman. On a tour of England in 1963 Procter scored 549 runs at 48.25 in 15 matches. He bowled just 48 overs and took seven wickets. On that trip Gloucestershire coach Graham Wiltshire saw the quality of the young South Africans, and the club’s off spinner David Allen, selected for England’s tour of South Africa in 1964/65, was tasked with finding two youngsters to join the county. He was given a short list of six, including Barry Richards. Procter’s name wasn’t on the list, but a good friend of Allen, former Springbok skipper Jackie McGlew, recommended Procter. The pair were duly offered contracts which they accepted.

In 1965 players had to have a residential qualification in order to play in the County Championship. Lacking that Procter and Richards spent their summer in the second eleven where Procter headed the batting averages and was second in the bowling, with 53 wickets at just over 13. There was one First Class match the two youngsters could play in, against their countrymen who were touring that summer. The game was spoiled by the second and third days being washed out, but on the first day Procter and Richards added 116 for the fifth wicket to take their side to respectability. Wisden described Procter’s role as dominant. He hit fourteen fours in an innings of 69.

Not yet ostracised from the sporting world the pair decided to break their residential qualifying to return to home in 1965/66 in order to improve their Test prospects. Procter, still not 20, averaged more than 50 with the bat. His first century came in difficult circumstances against Transvaal. He came to the crease at 19-4 with Richards retired hurt as well. He batted for the rest of the day with his captain, ending up contributing 129 to a stand of 277. The following season his batting fell away, but Procter the bowler then came to the fore, his 49 wickets costing just 15 runs each. The Australians visited South Africa for a five Test series and despite the existing side’s victory in England in 1965 Procter got himself into the squad. He was twelfth man for the first Test, but that didn’t keep him out of the action as he held two catches as substitute in South Africa’s victory.

After Australia squared the series in the second Test the debut finally came in the third. There were seven wickets for Procter, followed by six more in the next Test. In the final Test, when South Africa sealed their 3-1 win, there were just two more wickets. With the bat Procter didn’t get going at all, his three innings bringing him 1, 16 and 0, but his bowling was sufficient to move teammate Peter Pollock to observe Procter’s role in the winning of this rubber was vital.

For the 1968 season English counties could, for the first time, employ an overseas player on a special registration which avoided the need to acquire any sort of residential qualification. There was only one permitted however and initially Gloucestershire joined in the auction for the signature of Garry Sobers. There may have been some regrets when the great man signed for Nottinghamshire, but they won’t have lasted long. Gloucestershire turned to Procter instead, and for fourteen summers he came back every year, always delivering the goods and, for the last five years, skippering the side. It was a little disrespectful to several other fine cricketers for the county to be dubbed ‘Proctershire’ during that time, but the soubriquet was given with affection, and seems not to have put any noses out of joint.

The second and final Test series of Procter’s career took place in 1969/70. Again it was a home series against Australia. South Africa won each of the four Tests and the measure of their superiority was that the ‘closest’ of the matches resulted in victory by 170 runs. In addition to Procter there were three other all-rounders in the South African side; Eddie Barlow, Trevor Goddard and ‘Tiger’ Lance. All went in to bat above Procter, who batted at seven in the first Test, eight in the second and fourth and as low as nine in the third Test. He wasn’t played for his batting, and he never arrived at the crease in any sort of crisis, yet his contributions were 22 and 48, 32, 22 and 36* followed by 26 and 23.

It was with the ball that Procter left his indelible mark on the series. At 23 he took 26 wickets in the four Tests at the remarkable average of 13.57. He showed great consistency, taking wickets in every Australian innings, and ending the series with what was to remain his only five-fer, 6-73 to secure victory. The Australians led by Bill Lawry were not a great side, and arrived in South Africa on the back of a gruelling visit to India, but Procter’s achievements still showed enormous promise for the future. Sadly for him and cricket watchers the world over his skills were never seen at the highest level again.

The nearest Procter got to playing ‘big’ cricket again was when he appeared in the series played by a Rest of the World XI against England in 1970. The five matches were played with all the trappings of full Tests and were the closest Procter got to playing against England. He averaged 48.66 with the bat, again from way down the order, and his 15 wickets cost 23.93. He also featured in the World Series Cricket World XI in 1977/78 and 1978/79 and he made his mark then as well.

After his exertions against England in 1970 Procter returned home to play for what at that time was still known as Rhodesia in the ‘B’ Section of the Currie Cup. He scored five consecutive centuries to put him one more three figure innings away from equalling the record of six, held jointly by CB Fry and, inevitably, Sir Donald Bradman. There were and are some in Australia and England who seek to devalue Procter’s achievement by pointing to the second division nature of the opposition. But Procter could only score runs against the opposition he faced, and that included Test player Jackie Botten, and men like Clive Rice and Alan Kourie, who would undoubtedly have had long Test careers had the exile not been imposed.

The chance to equal the record came against Western Province, who had finished the ‘A’ Section season in second place. They reduced Rhodesia to 5-3, and the possibility faded. Procter, for once batting at four was dropped at slip before he got going but when his side’s innings closed at 383 he had contributed what was to remain his highest ever innings, 254. The chance to then break the record came in a famous game between Transvaal and a Rest of South Africa team.

In 1971/72 South Africa were due to tour Australia. Although that was a year away there were already suggestions being made that the tour would have to be cancelled. The South Africa Cricket Association were desperate for the tour to go ahead and asked the government to allow them to select the two best non-white cricketers in the country for the party.

The Transvaal and Rest of South Africa match was in the nature of a trial for the selectors to look at candidates for the touring party. A couple of days before the scheduled start it was learnt that the government had refused SACA’s request. The players were furious and Procter was one of the main protagonists in ensuring their views were heard. There was talk of a boycott of the match, but in the end the players were persuaded there was a better way.

The action was supported by all of the Rest’s players. The Transvaal side were less solid, voting 7-4 in favour of the proposed action, but all took part. The match is still remembered for the players’ action in leaving the field after a single delivery. Barry Richards pushed the ball for a single after which he and his partner Brian Bath left their bats in the middle and all the players walked back to the pavilion. They issued a joint statement before returning; We cricketers feel that the time has come for an expression of our views. We fully support the South African Cricket Association’s application to invite non-whites to tour Australia, if they are good enough, and further subscribe to merit being the only criterion on the cricket field.

Nothing changed of course, and South Africa didn’t play Test cricket again for more than twenty years. But it was not long before the first steps towards multi-racial cricket were taken, so whilst the protest didn’t achieve its aim, it certainly contributed something to the impetus for change. In the circumstances it was understandable that the main story coming out of the game was not Procter managing to break his own wicket from the orthodox left arm spin of Peter De Vaal for 22.

In terms of runs scored 1971 was Procter’s best ever season for Gloucestershire. He scored almost 1,800 runs at 45 with seven centuries. His bowling brought him 65 wickets at less than 19. He certainly carried the county that summer, comfortably topping the batting and bowling averages. This was also the summer of his own most memorable match in England, against a Geoffrey Boycott led Yorkshire side at Sheffield. Gloucester faced a fourth innings target of 201 in, effectively, forty overs. At tea they were 28-3 and Boycott thought there was no chance. He decided to give John Hampshire’s occasional leg spin a try in order to buy a wicket. Hampshire conceded 38 runs in three overs and the chase was on. Such was the power of Procter’s 111 that the target was reached with six overs to spare.

It was inevitable, given his unusual action, that injury would take its toll on Procter and the right knee that took all the strain played him up increasingly and eventually he needed surgery on ligament damage in early 1975. He did make a comeback in July, bowling off breaks. Procter wasn’t a stranger to finger spin by any means and his best ever figures, 9-71 against Transvaal in 1972/73, were essentially as a spinner. Opening the bowling Procter soon dismissed former Middlesex player Norman ‘Smokey’ Featherstone for just a single, but after that the second wicket pair posted a century partnership. Procter could see the wicket was turning so switched to off spin, and quickly picked up eight of the remaining wickets to take his side to victory.

In the Gillette cup tie against Lancashire in 1975 Procter was getting nowhere with the off spin against Clive Lloyd, so decided to try the knee out and started to bowl fast. It wasn’t long before he was crumpled in a heap on the ground and in need of assistance to get back to the pavilion. The injury seemed to be a bad one, and there were few watching that day who ever expected to see Procter bowl fast again.

The knee troubled Procter for the rest of his career, but it didn’t stop him bowling fast, and the captaincy of Gloucester, to which he was appointed for the summer of 1977, seemed to further inspire him. With much the same side as the county had had for some years Procter led by example as he almost steered his side to their first County Championship. He was the leading bowler in the country, taking 109 wickets at a tic over 18. No one else in the country took 100 wickets, and indeed no one else had more than 88. In his own opinion in a Benson and Hedges cup final against Hampshire he bowled as fast as he had ever bowled.

Gloucestershire set Hampshire what seemed a straightforward target of 181, although after seven overs the contest seemed over as Hampshire stood at 18-4. Procter bowled Gordon Greenidge with the fifth ball of his third over, and the first three deliveries of the fourth saw Barry Richards, Trevor Jesty and John Rice join him back in the pavilion. With Procter taking a rest Hampshire got back into the game and it took another couple of late wickets for Procter in his second spell to confirm victory by seven runs – his final figures were a remarkable 11-5-13-6.

Throughout his career Procter dealt in the spectacular. In addition to that effort against Hampshire there were four hat tricks in the County Championship. On three of those occasions he added a century to the hat trick. Against Essex in 1972 both feats were on the same day, and against Worcestershire in 1977 the century came before lunch. The third occasion was against Leicestershire two years later, and again the century came before lunch before the hat trick was part of a match winning 7-26 in 17.5 overs. The only one of the four that was not accompanied by a century came against Yorkshire, in the very next game after the Leicestershire match when three booming inswingers trapped Richard Lumb, Bill Athey and John Hampshire lbw.

Procter’s rich vein of form continued after the consecutive hat tricks. In the next game, badly affected by rain, he took five Worcestershire wickets. Then Surrey felt the weight of the Procter bat as he scored a fifty and a century against them, although despite three second innings wickets from Procter he couldn’t stop the Brown Caps getting home by the narrowest of margins, a single wicket. If that were not enough for one man Procter left his mark on a fifth successive game when he hit six consecutive deliveries from Somerset orthodox left arm spinner Dennis Breakwell for six before Ian Botham dismissed him just short of a century. It must have been a summer Procter was disappointed to see the end of as after that he scored 92 against Warwickshire before, in the final game of the season against Northamptonshire, he scored yet another century and also took six wickets.

And Procter certainly didn’t restrict his best performances to the First Class game. In addition to his performance against Hampshire his was the starring role in Gloucestershire winning their first piece of silverware, the 1973 Gillette Cup. After choosing to bat Gloucestershire, like so many did with a 10.30 September start at Lord’s, struggled to 27-3 before Procter settled things down before eventually falling for 94, just short of a deserved century. There was no clatter of wickets for Procter with the new ball but he came back to take two late ones, and finish with the excellent figures of 10.5-1-27-2.

Prior to his late season surge of form in 1979 Procter had indicated that he had no desire to lead Gloucestershire again in 1980, and indeed that he may retire altogether. He was persuaded to change his mind, first about retirement and then about the captaincy. If not quite reaching the heights of 1979, when he got as close as he ever did to completing the double, Procter enjoyed a fine 1980 and by the end of the summer, at 34, he became qualified for England. There were certainly some who believed he should have gone to the West Indies with Ian Botham’s side in 1980/81, but it wasn’t something Procter wanted. He never suggested he wanted an England Test career, and the only real motivation behind the request was that this re-classification would allow Gloucestershire to sign an additional overseas player.

Sadly however 1981 was the end of ‘Proctershire’. The captain played until the beginning of July but the knee remained problematic, and he decided that his career in England was over. Three years later he announced his retirement in South Africa as well. He had led the South African side in one of the matches against Graham Gooch’s England rebels in 1981/82. He didn’t make the South African team for the fixtures in the following seasons against the strong West Indian rebels but, playing for Natal, his final First Class century did come against them.

Procter didn’t leave the game that had been his life for so long, and was appointed to the South African selection panel in 1985. In 1988 he briefly made a comeback, and played a couple of matches for Orange Free State in the 1987/88 season and one final one, aged 42, for Natal in 1988/89. He achieved nothing of note. In 1991 Procter was back in England, having signed a three year contract at Northamptonshire as Director of Cricket – effectively team manager. A side who in recent years had often been guilty of under-achieving won the Nat West Bank Trophy in 1992, their first silverware for a dozen years and only their third title ever. Procter’s success was taken note of at home and at the end of the 1992 summer he was released from the last year of the contract to take up the position of South African coach.

Three years later Procter was appointed an ICC Match Referee, a job that embroiled him in some controversy. He had the misfortune to be in charge of the 2006 Oval Test against Pakistan that was forfeited by the visitors when they refused to resume play over concerns about allegations of ball tampering. Perhaps more draining was ‘Monkeygate’ when Procter banned Harbajhan Singh for three matches for racially abusing Andrew Symonds. On appeal Singh was vindicated, the Judge who heard the appeal taking a very different view of the evidence to that taken by Procter.

There were no more refereeing assignments for Procter after that Australia/India series and he doubtless thought he would find his new employment as convenor of the South African selectors rather more congenial, although in fact that lasted less than two years. Since then Procter’s time has been taken up with the Mike Procter Foundation, a charity that supports the most underprivileged children in Durban.

In September of this year Mike Procter will celebrate his 70th birthday. Despite a number of visits to his surgeons over the years, for work on both knees and both shoulders, he remains fully committed to his charitable work. He no longer plays cricket of course, but he will be talked about for as long as the game is played. The main talking point is the straightforward one as to how many Test wickets and at what cost would the man who took 41 at 15.02 might have finished up with had he been born twenty years later. And of course how many runs, at what average and strike rate, might he have scored.

Perhaps worth giving a few more details about those innings late in the 1979 season:

– 100* in 76 minutes against Surrey

– 93 in 46 minutes against Somerset

– 92 in 35 minutes against Warwicks

– 100* in 57 minutes against Northants

Comment by AndrewB | 8:03pm BST 9 May 2016