Masterly Batting

Dave Wilson |

In 2012, Patrick Ferriday’s first book When the Lights Went Out, covering the 1912 triangular tournament, was voted CricketWeb’s Book of the Year. Patrick’s new book, Masterly Batting – 100 Great Test Innings, is due out next month and is illuminated by contributions from the likes of David Frith and Ken Piesse writing on their boyhood heroes, Stephen Chalke on one of the greats of the inter-war years, Rob Smyth and Telford Vice on modern giants and Derek Pringle writing from the best view in the house, the other end of the pitch.

CricketWeb is delighted that contributions have also been made by no fewer than six of our feature writers – Martin Chandler, Sean Ehlers, David Taylor, Gareth Bland, David Mutton and Dave Wilson. As a taster for the book’s upcoming release we are proud to present several extracts from each of our authors, in this second part featuring David Taylor and Sean Ehlers writing on innings more than 100 years apart.

Graham Gooch – 135

England v Pakistan, Leeds 23-26 July 1992

by David Taylor

England and Pakistan went to Headingley for the fourth of a five-Test series, with the tourists 1-0 up following a two-wicket win in a low-scoring thriller at Lord’s. For this match the England selectors made a number of changes, Alec Stewart taking over as wicket-keeper while Somerset seamer Neil Mallender came in for his debut. Stewart dropped down to number four and Michael Atherton resumed his place as Graham Gooch’s opening partner, a combination that had already yielded some big stands.

Javed Miandad won the toss for Pakistan and chose to bat but, with only Salim Malik standing firm, the tourists soon subsided to 80-5. Mallender was among the wickets as ‘the ball came off sluggishly, occasionally keeping low and always seaming and swinging’. With bad light forcing an early finish, Pakistan closed on 165-8. Next day Malik continued to marshall the tail but ran out of partners on 82 with the total 197.

One year earlier, on this ground, Gooch had given a masterclass against the feared West Indies attack, carrying his bat and enabling England to record their first home win against those opponents for 22 years. The bowling on this occasion was hardly less formidable, even if they were more likely to target the batsman’s toes than his helmet. Wasim Akram and Waqar Younis, left and right arm, swung the ball at express pace; the murky Leeds sky perfect for their style of bowling. They were backed up by Aaqib Javed, an English-style seamer, and the leg-spinner Mushtaq Ahmed, wily beyond his years. All of the quick men had experience with counties, indeed Waqar had taken over a hundred wickets for Surrey in 1991. Wasim, the oldest of the four at 26, was remembered by all from the tour of 1987 and of course, they’d seen off England in a World Cup final in March.

The opening stand of 168 by Gooch and Atherton was their seventh of over 100, and unusually the junior partner matched his captain run for run, contributing 76 before losing his off stump to Wasim. Gooch had survived two lbw appeals from Waqar in the 40s, but replays showed that in both cases the in-swing would have taken the ball past leg stump. His persistence in playing forward to counter the unreliable bounce was a masterpiece of planning and execution, driving the pace bowlers to distraction as umpires Palmer and Kitchen refused to guess. Once Atherton had been replaced by Robin Smith, Gooch took command, striking Mushtaq over long-on for six and long-off for four.

His seven-hour 135 was put into perspective by the dismal collapse that followed his dismissal to Mushtaq’s googly. With Mallender taking five second-innings wickets, England were left just 99 to level the series – two weeks later Wasim and Waqar showed that Gooch’s defiance was only temporary.

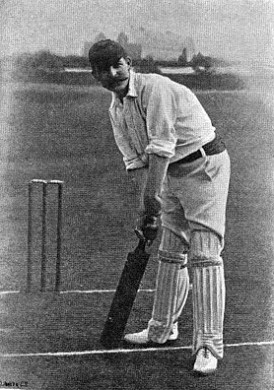

Allan Steel – 132

England v Australia, Lord’s 21-23 July 1884

by Sean Ehlers

In Victorian England, ‘professional’ was a dirty word. Training for sport was almost considered heresy with a true champion expected to be born with a natural ability. In cricket, like no other sport, the professional player was maligned by the establishment, a hero to the masses he was considered nothing more than a servant to the amateur. He had separate changing rooms, ate with the public instead of in the dining room and had to call the amateur ‘Sir’ or ‘Mr’, he in turn would be referred to by only his surname.

Allan Gibson Steel, was an amateur through and through. He attended Marlborough and Cambridge, where he gained blues for cricket, rugby and racquets. At his peak he was considered an all-rounder second only to W.G. Grace but unfortunately his employment as a barrister severely limited his cricket. During the 1880s Steel was a first-choice selection for England and he featured in the first three-Test series played in the ‘old dart’ in 1884. Australia had been in a strong position in the first Test of the summer but the loss of the first day (Tests being only three-days duration in England) resulted in a draw. Both teams were greeted by unsettled weather for the second match – the inaugural Test at Lord’s.

Australia, batting first, collapsed to 93-6, but ‘Tup’ Scott’s 75 led Australia to a competitive 229. Scott may have felt particularly aggrieved as it was his own captain Billy Murdoch, acting as substitute for Grace, who took the catch to dismiss him. The injury did not prevent the good Doctor opening the innings and by the end of day one England had reached 90-3. Steel would join the not out batsman, George Ulyett, at the commencement of day two in what appeared to be an evenly-poised game, although Australia possessed the trump card in the form of the greatest bowler of the period, Fred ‘the Demon’ Spofforth.

The delicate balance was quickly disturbed by Steel who was so severe on Spofforth that ‘he sank at once into a second rate bowler’. The Australian attack was played by Steel with ‘ease and confidence’ in a display of ‘magnificent batting’. He gave one difficult chance at 48, off Spofforth, and on such things games of cricket can be decided. If the ‘Demon’ had claimed Steel at this juncture, with his confidence up the great bowler may well have won the match for his country. As it was Steel did not offer another chance until well past his hundred and was not dismissed until he had reached 148 in under four hours.

Faced with a deficit of 150, Australia, through the big hitting Percy McDonnell, started the second innings with aggressive intent. However it was A.G. Steel’s day, he took the ball and bowled the dangerous McDonnell; with this Australia collapsed for 145 and were beaten by an innings. The third Test ended in a draw and so England, with the strength of Steel, had won the Ashes.

Good to see AG Steel in there – not very well known today, but I recently suggested to somebody that he might be Liverpool’s greatest cricketer. Unless anyone can think of a better candidate?

Comment by stumpski | 12:00am BST 19 August 2013