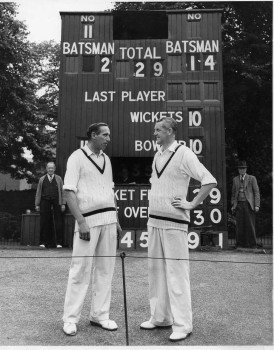

Jackson and Gladwin

Martin Chandler |

In his 1986 autobiography Trevor Bailey told the story of a match between his county, Essex, and Derbyshire. He summed up the defeat by writing; Our two chief executioners, on that occasion, and many others, were Les Jackson and Cliff Gladwin, who for more than a decade were the most feared and effective opening attack in county cricket.

Between 1946, when Gladwin resumed a county career that was four matches old when war broke out, and 1963 when Jackson retired, England played 144 Test matches. Gladwin was selected for eight of them and Jackson for just two. Their First Class records are remarkable. Jackson took 1,733 wickets at 17.36. Gladwin’s record is marginally inferior, 1,635 wickets at 18.30.

At international level Gladwin, arguably, got a fair opportunity to prove what he was worth, but Jackson most certainly didn’t, and more than a decade after their hero departed this mortal coil the way he was treated by England’s selectors still rankles with Derbyshire supporters.

Both men came from a mining background, as had so many who led the Derbyshire attack before them. For Gladwin there was a family connection with Derbyshire cricket his father, also a seam bowler, having played briefly for the county on either side of the Great War. At 23 Gladwin Junior made his bow in 1939, but there was no hint of what was to come, there being just 24 wicketless overs for him.

Five years younger than Gladwin Jackson began his Derbyshire career in 1947, and their much lauded partnership began in earnest the following summer. As with many fine bowling pairings the two men were very different, both in their personalities and the way they bowled. Jackson was a phlegmatic character who bore his constant rejection by the England selectors without complaint. Like all bowlers he did not like batsmen, but he was tolerant and understanding in the field, never complaining when, as happened not infrequently, catches were put down from his bowling. Gladwin on the other hand would berate anyone who gave a batsman a life. A bowler who begrudged the batsman every run he scored Gladwin never lost track of his figures, and would try and correct any scorer who he believed had done them a disservice.

With the ball both men had economical actions and seemingly endless stamina, but Jackson was undoubtedly the faster of the two. He was never genuinely quick, but wasn’t far short of it at times and his height and the bounce he could extract from any surface caused batsmen plenty of discomfort. Jackson also moved the ball both ways, but there was no point in asking him about what he did to the ball, his answer being that he simply held the seam of the ball upright and then buggered about with it until something happened. He was also metronomically accurate, both his front foot and the ball consistently landing in the same place.

Gladwin was a good deal slower than Jackson but was just as accurate. His stock delivery was an inswinger bowled to a ring of close catchers on the leg side waiting for a mistake from the batsman. Almost a quarter of his wickets fell to catches in the leg trap. He could make the ball hold its line as well and, whilst in South Africa in 1948/49, where conditions took much of the danger out of his stock delivery, he developed a leg cutter as well. So keen to bowl was Gladwin that if nothing was happening for him he would also from time to time slow down and try his hand at off spin.

After the war England’s pace bowling stocks were at a low ebb, and in 1947 even its stand out performer, Alec Bedser, endured a lean summer in the Test series against South Africa and Gladwin’s county form earned him a place in the side for the third Test. England won the match and the series 3-0. Gladwin’s figures perfectly demonstrated his nagging accuracy as his returns were 50-24-58-2 and 16-6-28-1. Perhaps surprisingly in light of that he was dropped for the fourth Test, but then brought back for the last. That match was drawn, South Africa ending up 28 short of a target of 451 with three wickets in hand. There were no wickets for Gladwin, although his steadiness with the ball helped to thwart South Africa. He also contributed a useful unbeaten 51 to England’s first innings.

There was no place for Gladwin against the 1948 Australians but he toured South Africa in 1948/49 and played in all five Tests. He took only eleven wickets, but was shown great respect by the South African batsmen and bowled with all his usual economy. His contributions with the bat were also modest, but he was facing the bowling in the first Test when, for the first time in a Test match, a match was won from the last possible delivery as Gladwin and Bedser scrambled a leg bye to get England home by two wickets.

The 1949 New Zealanders, unlike the two previous sides from the Shaky Isles, and indeed the next six to visit, were a nut England could not crack. In the first of the four drawn Tests Bedser went wicketless and was dropped, to be replaced by Gladwin for what proved to be his final Test, but he did little better claiming just a single wicket. He was replaced for the third Test by Jackson, whose 2-47 and 1-25 were certainly a creditable start, but by the final Test Bedser was back in form and restored to the side in Jackson’s place. It would be a remarkable twelve years before Jackson played his second and final Test.

By 1961 Jackson was 40. Inevitably he wasn’t quite the bowler he had been, and he also had a few injury problems at the start of the summer. Nonetheless his reputation amongst his peers was undimmed. Fred Trueman, at that time in his pomp, had always been a great champion of Jackson. He praised him in all of the many books he wrote and in his final autobiography, published in 2004, he summed up on the subject of Jackson with; Why he was not chosen more often for England is a mystery to me to this day. Quite simply, any number of bowlers chosen ahead of him in the 1950s were only half the bowler Les Jackson was.

As well as Trueman many others had been making similar comments for years, but in 1961 the former Australian fast bowler Ray Lindwall was in the press box. He added fuel to the fire by reporting that back in 1948 (Jackson’s first ever season) Sir Donald Bradman considered Jackson the best bowler the Invincibles had faced all summer, and that the Australians were both surprised and relieved not to have met him in the Tests.

Lindwall made his comments after a rain ruined match between Derbyshire and the tourists in which Jackson recorded figures of 10-7-9-1, and it was therefore slightly less surprising than it might have been when Jackson was called into the England side for the third Test of that 1961 series as cover against the possibility of Brian Statham being unfit to play. Lindwall’s words and those of Trueman were no doubt listened to but, with Gubby Allen still a hugely influential figure, the man primarily responsible for the selection seems almost certainly to have been England captain Peter May. Before the match began Statham failed a fitness test, and Jackson played.

The match proved to be the only one of the series that England won and is remembered as ‘Trueman’s Match’ for the eleven wickets that the Yorkshireman took, but Jackson was also superb, taking two wickets in each innings and bowling a total of 44 overs for just 83. Three of the four were good wickets as well; Peter Burge, ‘Slasher’ Mackay and Colin McDonald whilst the fourth, Wally Grout , was no rabbit. In an autobiography published a few years later Ted Dexter wrote; On a slow pitch he bowled with deadly accuracy to keep the scoring down on the first day ……. it was a brilliant piece of bowling which was worth many wickets to England as the game progressed. It must be likely that, had Statham remained injured, Jackson would have played for the rest of the series, but the Lancastrian was back for the fourth Test so the selectors decided they could afford to look to the future, and gave Jack Flavell a debut as support for Statham and Trueman.

Were the Derbyshire pair badly done to? The first place to look must be the Test records the two men achieved in those matches in which they were able to play. Doing so is of some assistance with Gladwin because, although his economy rate is, across the entire history of Test cricket, second only to that of William Attewell (who played ten times for England against Australia in Victorian times) his haul of 15 wickets at 38.06 does tend to suggest he wasn’t sufficiently penetrative at the highest level and that, with eight caps to his name, he had sufficient opportunity.

It is also true however that, after he was last selected in 1949 at 33, Gladwin enjoyed a run of remarkable consistency. He played on for nine more summers and never took less than 94 wickets, nor paid a higher price for his victims than 19.36. His last season, that of 1958, saw the 42 year old sign off with 123 wickets at 16.34, returns that put him thirteenth in the First Class averages. At the top that summer was Jackson – 143 wickets at an astonishing 10.99. It is an average that had not been bettered since 1894, and has not been approached since.

For Jackson, the cause of his partner’s failure to secure more caps was straightforward. In the last game of that 1949 New Zealand summer Derbyshire played a Championship fixture at Lord’s. At an important point in the visitors’ second innings teammate Alan Revill ran Gladwin out. When a livid Gladwin got back to the dressing room he threw his bat to the floor, from where it bounced up and through a window. Gladwin was hauled over the coals by the secretary of the MCC and that, in Jackson’s view, was the incident that ensured Gladwin’s Test career was consigned to history.

Turning to Jackson himself two Test matches is palpably insufficient on which to judge a man’s ability to play at the highest level particularly when, as Jackson did, his performances could not be described as anything other than highly competent – 7 wickets at 22.14 against two strong batting sides is certainly all that could reasonably be expected of him.

One of the explanations put forward is the disapproval on high of Jackson’s action which, it seems can be conceded, could not be described as a thing of beauty. There was nothing of the Larwood or Lindwall about Jackson. He was never coached and had a short run up of thirteen paces culminating in a low armed slingy delivery which more than one who has seen both has described as reminiscent of Jeff Thomson without the extreme pace. Certainly there was little from the MCC Coaching book on view and indeed at one point in 1949 Jackson was packed off to Alf Gover’s indoor school in London. Then the foremost coach in the game Gover had a good look at Jackson, left the basic action alone and sent him back with just a few suggestions as to how he might improve his performances.

How much were the selectors influenced by the fact that Derbyshire was not a ‘fashionable’ county? This is one I used to struggle with as in my youth Mike Hendrick, a decent bowler but one who never ran through sides at Test level, was an England regular, but then in the 1970s county cricket was at its most egalitarian. In truth however this almost certainly was a factor back in the 1950s as must the fact that both Jackson and Gladwin were from working class mining backgrounds. The hugely influential Allen is said not to have favoured either man, neither of whom merit so much as a mention in EW ‘Jim’ Swanton’s hagiography of Allen. Swanton was cut from much the same cloth as Allen so in some ways that is not surprising, but at least in other writings he made it clear he rated Jackson in particular as a bowler of high class.

A look at the fate of some other Derbyshire seam bowlers does however suggest an element of discrimination. As well as Jackson and Gladwin, Bill Copson and George Pope were fine bowlers either side of Word War Two who had career averages below 20, yet Copson was capped just three times and Pope once. Before the war Pope’s brother Alf was almost as effective and was never picked at all. Of a previous vintage Arnold Warren was selected only once, and Billy Bestwick not at all. After Jackson and Gladwin Harold Rhodes was capped twice, and the unrelated Brian Jackson was ignored despite, like Rhodes, having a career average lower than twenty. It is true there were question marks over Rhodes’ action (although he was to be exonerated) but for the younger Jackson there is no obvious explanation, other than bias, for his being overlooked.

Were Jackson playing today it would not assist that, as a batsman, he was very much a tailender. That would not have been considered irrelevant in the 1950s, but whilst the game was changing the days when an inability to wield the willow in any meaningful way might militate against a top class bowler being capped were still a couple of decades away. The truly hopeless batsman takes more wickets than he scores runs, a feat Jackson missed, albeit not by a great distance. His career high score was however a relatively modest 39. He chose good opponents for it however as he shared in a last wicket partnership of 65 in half an hour against Yorkshire in 1951. In the final analysis without Jackson’s runs the match would almost certainly have been lost rather than, as they did, Derbyshire salvaging a draw.

Unlike Jackson Gladwin was, if never quite an all-rounder, no mug with the bat. In the late 1940s, when he played all his Tests, he was a more than serviceable late order batsman who, in 1949, was within 86 runs of the double. He was never so close again and as the 1950s wore on his returns with the bat were less impressive, but he was a better batsman than many seamers who played Test cricket ahead of him so batting certainly didn’t contribute to his omission.

Jackson himself would point to the quality of the competition that he and Gladwin had in the 1950s when bowlers like Bedser, Statham, Trueman and Frank Tyson ruled the roost. If that were not enough men like Derek Shackleton and Peter Loader were destined to spend most of the decade watching and waiting. That does not however explain or excuse the selectors ignoring Jackson and Gladwin in the early 1950s when England were desperate to find a new ball partner for Bedser. The 1950/51 Ashes series was lost 4-1 and the only specialist new ball bowler England had to complement Bedser and Trevor Bailey was John Warr. The Middlesex amateur took a single Test wicket for 281 runs. When it was realised that reinforcements were needed the selectors should have sent Jackson, but in fact went for a twenty year old with just half a season in the First Class game behind him. Had Statham not gone on to achieve what he did that decision would have seemed as strange today as it did in 1951.

It is inconceivable that either Jackson or Gladwin would not have done considerably better than Warr, despite another suggestion sometimes made that Jackson did not succeed outside the seaming tracks in Derbyshire. It is true that he was immensely successful on his home wickets in Derbyshire, which not unnaturally were prepared with himself and Gladwin in mind and indeed a close examination of his record does reveal Jackson took more of his wickets at home than away. But he still took plenty elsewhere and whether the disparity in success rates is significant is another question entirely.

The England captain in 1950/51 was Freddie Brown, an old fashioned amateur. Brown was a tenacious cricketer who made the best of the ability that he had but his man management skills left something to be desired, a good example being the way 19 year old all-rounder Brian Close was treated on that trip. There can be no doubt that Brown, like Allen later, did not want a former miner in the side although he does at least mention Jackson. The context is interesting in that there was one occasion when Brown did captain Jackson. The comment in Brown’s 1954 autobiography was; When there is anything in the wicket Jackson can usually be relied upon to use it well. His pace is quicker than most people imagine, but his arm is definitely on the low side, and I am afraid he is somewhat liable to break down. The initial concession had to be made, as the match when Brown led Jackson was the 1949 Test Trial, when he took 6-37 for the North against the South as the southerners were shot out for 85. The comment about Jackson breaking down is, on the other hand, somewhat bizarre. He suffered the occasional injury and missed matches, but when he was playing nothing stopped him doing a job for his captain.

In many ways related to the above is the perception that Jackson, like Gladwin in South Africa, would not have been a success overseas. I have also read that his physique told against him as well. He had, courtesy of his time extracting coal from the Whitwell pit, a strong and powerful upper body to combine with what in comparison were a rather spindly pair of legs that would, the theory went, let him down overseas. We will never know, as Jackson never toured with England and just once, in 1950/51, did he play abroad. Selected as a member of a powerful Commonwealth XI Jackson went to India. Unfortunately an elbow injury meant that he played in just two First Class matches. The pitches did not help him and he was not much used, but figures of 3-35 in those two games indicate he was probably perfectly capable of adapting to sub-continental tracks had he ever been given another opportunity to do so.

The end of Gladwin’s career came in 1958. This was the year the law changed to limit the number of fielders behind square on the leg side thereby outlawing Gladwin’s leg trap. He turned 42 at the start of the summer but as noted despite the law change he adapted very well – there are not very many whose final summer brings them 123 wickets at 16.34. After he retired Gladwin enjoyed continuing success in the leagues and then made a living running a sports shop. Sadly he did end up falling out of love with the game, less than happy at being failed when he sought to obtain a coaching qualification. He died in 1988 at the age of 72.

For Jackson too the leagues were the first stop after retirement. Initially he had a summer with Enfield in the Lancashire League, before moving on to the Bradford League where he had six seasons with Undercliffe. Outside the game Jackson continued to work for the National Coal Board, as he had done throughout his adult life. His role changed of course, leaving the coal face when he started bowling for Derbyshire and becoming a chauffeur. He made a brief comeback of sorts in 1991 at the age of 70 when he was persuaded to bowl the first over of a charity match. Happy to oblige Jackson paced out his 13 yard run and, in the manner of yesteryear, made sure Leicestershire skipper Nigel Briers had to play at each of the six deliveries. Les Jackson died in 2007 after a short illness. He was 86.

Great article. Without doubt Derbyshire bowlers were discriminated against. In 1905 Billy Murdoch told the visiting Australians that the best fast bowler in England was Warren, yet he played only one Test and took five wickets in an innings. Watching Derbyshire in the 1960s you could not reach any other conclusion when Harold Rhodes and Brian Jackson were the best pair of opening bowlers in the country.

Comment by Ric Sissons | 8:38pm GMT 28 December 2018

Nice article! Enjoyed reading that and very fair comments. From what I have been told Cliff was a very good county bowler. Les was outstanding and would have taken wickets at top level.

Comment by Steve Dolman | 8:07pm GMT 29 December 2018