Between Gregory and McDonald, and Lindwall and Miller

Martin Chandler |

Under Warwick Armstrong’s astute leadership Australia pioneered the use of two quick bowlers at the start of an innings. Jack Gregory and Ted MacDonald were both genuinely fast and their hostility saw Armstrong’s side to a sequence of eight consecutive victories over England between 1920 and 1921. It is perhaps surprising then that it was a quarter of a century and another World War later that, in 1946, Don Bradman was, with Ray Lindwall and Keith Miller, able to repeat the tactic.

For the remainder of the inter-war period Australia’s matchwinners with the ball were spinners, in the main Clarrie Grimmett, Bill O’Reilly and ‘Dainty’ Ironmonger with help from Arthur Mailey and ‘Chuck’ Fleetwood-Smith. The Australian pace attack was not quite the ‘gesture to convention’ that India used in the 1960s and 1970s, but fast bowling was not the way they expected to win Test matches.

By the time England visited in 1924/25 McDonald was gone, playing professionally in the Lancashire League whilst waiting to acquire the residential qualification that enabled the Red Rose, for the only time, to dominate county cricket in the late 1920s. Gregory was still around, and played in all five Tests taking 22 wickets, but the cost was 37.09, and he wasn’t quite the bowler he had been four years previously.

In 1924/25 Gregory did have a pace bowler to open with, although Charlie Kelleway was no more than fast medium. In fact Kelleway bettered Gregory in the averages, albeit he took only 14 wickets, but the cost of those was a creditable 29.50 each. He proved rather more economical than his more illustrious partners but he was no youngster, and despite his bowling being described as lively and animated he was already 38. Kelleway had made a Test debut back in 1910. He was a good enough batsman to end with an average of 37.42 and, when his Test career finally ended, four years later after a solitary wicketless Test in the 1928/29 Ashes, he had a tally of 52 wickets in his 26 Tests for which he had paid 32.36, so a genuine all-rounder if never a prolific wicket taker.

The only other Australians to provide a measure of pace bowling in 1924/25 were batsmen Jack Ryder and ‘Stork’ Hendry. Both were on the quicker side of medium pace, and it would be unfair to describe either as only occasional bowlers, but equally neither could claim to be a true all-rounder at Test level.

Australia won 4-1 in 1924/25 and Mailey had a big bag of wickets and Grimmett first appeared late in the series. In 1926 England had grown stronger and, in a famous match at the Oval, finally won back the Ashes by winning the fifth and final Test. There was some poor weather but the fact that in five Tests the Australian seamers took only four wickets between them is still remarkable. Gregory took three of those, at a cost of 99.33 runs each, and Ryder paid 142 runs for his wicket. The only other pace bowler in the party, 25 year old Sam Everett, did not get in the Test side at all.

In 1928/29 Percy Chapman’s England returned from Australian with a 4-1 Ashes triumph. In the first Test the Australian selectors reprised their opening attack of four years previously with Gregory and Kelleway. Neither played again. As noted the 42 year old Kelleway had gone wicketless and Gregory, who had at least taken three wickets, suffered a career ending knee injury in an attempt to take a catch from his own bowling from young English fast bowler Harold Larwood. Australia lost that match and the next three, an increasingly desperate selection policy entrusting the seam attack at various times to Hendry and Ryder, as well as Otto Nothling, Ted, a’Beckett, Alan Fairfax and Ron Oxenham, none of whom threatened any fireworks.

Australia’s consolation victory came in the fifth and final Test and, in large part, came courtesy of the efforts of a young fast bowler, Tim Wall, selected at 24 for his debut. Wall was not genuinely fast, but had a long run and a good action which, combined with his height, could make him a handful. In this match, which went into an eighth day, he took 3-123 and 5-66, looking particularly impressive for a time in the England second innings when rain briefly freshened the wicket.

When Australia reclaimed the Ashes in 1930 the best remembered contribution was the 974 runs scored by Donald Bradman, but the 29 wickets Grimmett took were vital as well. Wall was consistent, but lacked penetration and as far as the averages were concerned Australia’s most successful seam bowlers in the Tests were two medium pacers, Alan Fairfax and Stan McCabe.

The following summer West Indies visited Australia for the first time and a year later the South Africans. Australia’s margins of victory were 4-1 and 5-0, so they were not extended and the bowlers who did almost all the damage were Ironmonger and Grimmett. Wall went wicketless in his only appearance against West Indies, but did rather better against the South Africans. The only seamer to make any sort of mark against the men from the Caribbean was Alec Hurwood who, in the first two Tests, took 11 wickets at 15.45 before his employers declined to allow him to make himself available for the rest of the series. As a medium pacer Hurwood would not, however, have been the answer to Australia’s lack of pace in any event.

Much of the blame for the lack of Australian pace bowlers is put on the pitches and playing conditions in Australia at the time. Wickets were hard and true and Test matches were timeless. The only time bowlers could look forward to an advantage was on the notorious sticky wickets of the era, and when those conditions were encountered it was almost always the slower men who got to take advantage. That said visiting teams pace bowlers had their moments. Maurice Tate had a wonderful series for England in 1924/25 and he had some success four years later as well, as did Larwood and Leicestershire’s George Geary.

The West Indies bowlers were, overall, disappointing, but their attack was dominated by pace, all of George Francis, Herman Griffith and Learie Constantine bowling well at times. For the South Africans paceman Sandy Bell, despite that 5-0 hammering, emerged with the excellent return of 23 wickets at 27.13 even though Australia won three of the Tests by an innings and another by ten wickets. There was also success for pace bowlers in Australia in 1932/33. There are still those who cry foul where the success of Larwood and Bill Voce in that ‘Bodyline’ summer is concerned. The rights and wrongs of Jardinian leg theory cannot alter one thing however, and that is the 21 wickets at 28.13 that Gubby Allen took, bowling strictly conventional off theory.

The Australian selectors chose to fight Bodyline with spin and Wall, despite much off field clamouring for some selections to fight fire with fire. There is no doubt that there were some candidates, but skipper Bill Woodfull was not prepared to retaliate. The native Australian Eddie Gilbert for one was fit and firing and, in Bradman’s view, the fastest man he ever faced. But Gilbert had a much maligned action and never did play Test cricket. Also in the frame was the Australian Rules Footballer Laurie Nash, another who was fast and nasty and who doubtless because of that did not appeal to Woodfull. Last but not least was the man who did replace Wall in the side for the final Test, Harry ‘Bull’ Alexander. Genuinely quick but not very accurate Alexander took only one wicket, although by hitting Douglas Jardine more than once at least pleased the crowd if not his captain. Alexander never played for Australia again.

As in 1930 a Bradman inspired Australia won back the Ashes in England in 1934, though once more pace bowling did not make a major contribution. Between them O’Reilly and Grimmett took 53 wickets and, with six at 78.66 Wall led the pace bowlers. McCabe took just four wickets and the only other specialist seamer in the Australian side, Hans Ebeling, who took Wall’s place in the final Test, took three in what proved to be his only Test.

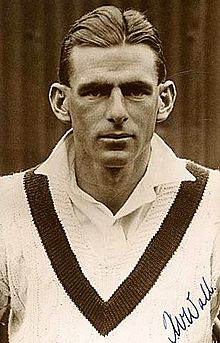

1934 was the end of the road for Wall, who announced his retirement, so the search began again. In Victoria there was Ernie McCormick, a bowler of real pace who had appeared against Tasmania in 1929, although it would be two years before he first played a Sheffield Shield fixture. Part of the problem was a period out of the game after an appendectomy, another was that there were not sufficient places in the Victorian line up to accommodate McCormick, Nash and Alexander.

A keen baseball player McCormick realised he needed to add something to his game in order to be certain of his place and in December of 1933 it was reported in The Australian Cricketer that he had developed the baseball art of swerve and incorporated that in to his bowling with such success that he now had six different type of delivery; fast and slow outswingers, a fast inswinger, a backspinner that kicked, a straight ball and an off break. The article concerned went on to explain that he had also cut his run up from 18 paces to 12 and had started to deliver the ball with a full body swing, rather than the square on approach he had begun his career with.

Another aspect of McCormick’s game, unusual for a tall fast bowler, was that he was a fine slip catcher and it was that, as much as his bowling that led to The Australian Cricketer calling for McCormick’s inclusion in the 1934 touring part through the early months of the year. Sadly for McCormick and his supporters however his one chance in 1934 to impress the selectors, a Shield game against New South Wales at the end of January, saw him record the disappointing analysis of 34-1-148-1.

The next Test series for Australia was their trip in 1935/36 to South Africa. The two countries had met in South Africa before, but only as an afterthought following a long Australian tour of England, so this five Test series was eagerly awaited. There was much disappointment when ill health prevented Bradman making the trip, but the party was still a strong one and the fast bowler who made the party was McCormick. The spin attack of O’Reilly and Grimmett were the driving force behind Australia’s 4-0 victory, but with 15 wickets at 27.86 McCormick’s first taste of international cricket was a successful one. As a tourist he was immensely popular, teammate Len Darling describing him as the funniest man I ever toured with, and the type that every team should have on a long trip.

Selected for the first Test of the 1936/37 Ashes series McCormick provided a sensational start. For the very first delivery of the rubber he produced a very rapid bumper which the Derbyshire opener Stan Worthington attempted to hook to the fence, but succeeded only in popping up for ‘keeper Bert Oldfield to help him become only the second bowler, and the last before Shane Warne, to take a wicket with his first delivery in Ashes cricket.

Batting at first drop for England was Arthur Fagg, who was quickly struck a painful blow about the body and then came very close to being hit on the head. It came as no surprise when, in trying to glance McCormick, he was dismissed for four. What was more surprising was the next delivery, the great English champion Walter Hammond doing no more than popping up a straightforward chance to one of McCormick’s two short legs.

Had Australia not then missed a couple of chances in the field (McCormick himself was responsible for the first, and he was the unfortunate bowler for the second) then England might not have been able to score the 358 that, after being 20-3, they recovered to. For McCormick there was time for just eight overs before an attack of lumbago prevented him bowling again in a match which, thanks to the intervention of the weather, England went on to win contrary to the form book and all expectations.

The lumbago had cleared up before the second Test, or at least it had for the first session when McCormick again bowled at great speed. Neville Cardus however felt he wasted his opportunity by bowling too many deliveries on a leg stump line and then, after lunch, Cardus complained of McCormick’s bowling becoming laboured and middle aged. That McCormick’s pace would drop significantly after his opening burst was an observation made by many. Thanks to a double century from Hammond England were able to declare on 426-6 and, fortunate again with the weather, they went on to win by an innings.

For the third Test at the MCG McCormick was sidelined by his lumbago, but there was no like for like replacement as the left arm wrist spin of Fleetwood-Smith replaced him. This time the Australian attack was opened by McCormick’s opening partner of the first two Tests, fellow Victorian Morris Sievers, and McCabe. Sievers was another tall man, but not much above medium pace. In this game however he had the good fortune to get the ball in his hands, in tandem with O’Reilly, when the weather chose this time to visit its wrath on England and he took 5-21 as they were dismissed for 76 in their first innings. Strangely this was to prove the end of Sievers’ three Test career as a fit again McCormick took his place for the fourth Test.

Australia, thanks in large measure to Bradman, completed the comeback by winning the final two Tests. There were two wickets in each innings for McCormick in the fourth match at Adelaide and then, in a move which surprised many, a second bowler of real pace was selected for the decider, like the third Test played at the MCG. Fellow Victorian Nash was the man picked and England skipper Allen was sufficiently concerned to make it clear to Bradman that he would not tolerate any intimidatory bowling by the Australians. His worries proved unfounded on that score, although bowling a conventional line Nash did take 4-70 in the English first innings and another in the second. For McCormick there were no first innings wickets, but he snared Worthington and Les Ames in the second.

After the series finished there was one final round of Sheffield Shield matches left, and for Victoria that meant a trip to Adelaide to play South Australia. Batting second the Victorians took a first innings lead of 31 at which point McCormick embarked on a sensational spell of bowling as he took 9-40 in eleven overs to leave the South Australian innings in tatters at 75-9. With victory all but certain and a rare chance of an ‘all ten’ for a pace bowler on offer Victoria’s skipper, Ebeling, tried to help. He had bowled eight overs himself, before bringing Fleetwood-Smith on. After two overs of Fleetwood-Smith Ebeling, concerned his unorthodox spinner might well inadvertently take a wicket, brought on Sievers with strict instructions to bowl wide and with the fielders all knowing that any opportunities had to go to ground. Inexplicably in the circumstances Sievers bowled Graham Williams with his sixth delivery – it is unlikely that Sievers was bearing a grudge after his omission from the fourth Test, and rather more likely that he thought it would appeal to McCormick’s sense of fun. In any event it was the only time in his career that McCormick took more than six in an innings and, having taken 3-56 in the first, the only time he had a ten wicket match haul.

McCormick came to England in 1938. The prospect of a genuine fast bowler performing for Australia for the first time since 1921 aroused much interest, a good deal of which was dashed in McCormick’s first appearance in the country. In the traditional tour opener at Worcester Australia batted first and (Bradman 258) spent the first day and an hour of the second putting together a total of 541. McCormick took the new ball. His first over consisted of 14 deliveries, and from one of the legal deliveries opening batsman Charles Bull, attempting a hook, deflected the ball on to his head and had to retire hurt. The second over comprised another 15 deliveries.

At this point Bradman spoke to the umpire and asked if McCormick was dragging. Dragging? He’s jumping two feet over was the response, and after an eight delivery third over McCormick was removed from the attack. He came back and was certainly better, but still managed a total of 35 no balls in 20 overs. The explanation given was that McCormick, who by now had a thirty yard run had not, in practice at Lord’s, been able to utilise his full run hence the Worcester game being his first opportunity to do so.

The first Test at Trent Bridge was drawn with England batting first and piling up 658-8 before Hammond declared. Australia had some awkward moments before a majestic innings from McCabe ensured they would save the game. McCormick took 1-128 but had no luck, a catch going down in the gully in his first over and Len Hutton shortly after that contriving to play the ball on to his stumps without disturbing the bails.

One record that McCormick will never lose was set up in the second Test at Lord’s when, after Hammond again won the toss and chose to bat, he became the first man to bowl a ball on live television. The delivery itself was uneventful, but there was life in the wicket and England were reduced to 31-3 with McCormick having Hutton and Charles Barnett caught at short leg and, between those two, bowling Bill Edrich. Unfortunately for Australia Hammond then played an innings like that of McCabe at Trent Bridge, and again the match was drawn.

The third Test, at Old Trafford, was abandoned without a ball bowled because of rain, and then the Australians won at Headingley to go one up in the series. McCormick dismissed Barnett in each innings, but that was his only success in what proved to be his final Test.

To the surprise of many McCormick was left out of the final Test at the Oval, the management having concerns, given a recent bout of neuritis in his right shoulder, about his ability to last the course in a timeless Test. In the event Hammond won the toss and an anodyne Australian attack was bludgeoned by England (Hutton 364) until Hammond finally took pity on the visitors and declared at 903-7. With Bradman and Fingleton both unable to bat the eventual margin of England’s victory was an innings and 579 runs. Had a risk been taken with McCormick’s fitness it seems unlikely that the margin would have been that great. As it was the Australian opening attack was McCabe and the equally gentle medium pace of Mervyn Waite. If ever a cricket match was decided on the toss of a coin it was this one.

On his return to Australia after the tour of England McCormick played for one more season before, at the age of 32, retiring at the end of the 1938/39 season. Outside the game he was a skilled jeweller, sometimes nicknamed ‘Goldie’ and in time he was commissioned to make the Frank Worrell Trophy. It amused him no end that he later got the same job again, only to lose it when the West Indies Board found the original. The sense of humour never deserted Ernie McCormick, who would relate to all comers a story about his attendance at the centenary Test in 1977, when a spectator greeted him with the question, didn’t you used to be Ernie McCormick?

England won by an innings and 579 runs at The Oval in 1938, not as shown.

The scorecard has long been burned onto my memory slate. I knew Ernie McCormick and he was a very funny man.

Comment by David Frith | 1:56pm GMT 26 January 2025