From Classical to Pop

Dave Wilson |

Rating the Test teams

The first cricket piece I ever published concerned my efforts to derive the Test team ratings from 1877-onwards. The ratings currently used by Reliance/ICC were developed by David Kendix in 2003, so I had thought it would be interesting to calculate the ratings back to the first Test for two reasons; first, general interest – it would be worth doing if only to see how great teams of the past (the 1902 Aussies, 1948 Invincibles, 1969 South Africans, 1980s West Indies) fared in the ratings as compared to teams such as the 2004 Aussies who fell within the ratings era, and secondly I had a plan to use the ratings to derive individual player ratings down the line. That first feature with Test team ratings was originally posted by the good people at howstat.com however this is no longer available on their site, so it can be found here, while the individual player ratings (christened “Series Points”) can be found in a series of articles originally posted on CW, but which are mostly collected together here.

Some years later, I moved away from Series Points as a way to rate players as that rating was based on performance in the series as a whole, rather than in actual matches, preferring instead to find the actual match impact, but in any case the historical ratings have proved useful in helping to rate players time and time again, as it enables taking into account the strength of the opponent faced.

As regards the Test team ratings I did actually suggest a revision to how they are derived in an effort to have them also take into account success away from home, as well as the degree of dominance, and that effort at “improving” the ratings can be found here.

Moving on to ODI ratings

What I’m going to do now is to develop impact ratings for individual ODI performance which will complement the Test player impact ratings, and the first step to achieving that is to find the historical ODI team ratings. Accordingly, this first feature looks at the 1970s. Hopefully arriving at ODI player impact ratings won’t take eight years, as the Test ratings did.

From classical to pop – the development of ODIs

Cricket in the 1960s was very different from the game we know today. There was basically Test matches and domestic championship cricket, and that was it – no one-day competitions, no T20; there had been for a long time the Gentlemen vs Players fixtures in England (actually since 1806) but the distinction between amateur and professional was formally abolished in 1962. There had been a number of attempts to make the game more attractive, including a committee formed near the end of the war in 1944 and led by Sir Stanley Jackson, which talked in grandiose terms about attacking play and a dynamic attitude to the game, though offered no real solutions for either and indeed rejected limited overs cricket and Sunday play; the Findlay report of 1937 had also warned against too much cricket. Proposals for restrictions on play in the county championship left open the possibility of a knockout competition, which got the press very excited, however nothing came of it.

Gentlemen and Players

As regards the distinction between Gentlemen and Players, this was increasingly becoming a grey area, with the appointment of Len Hutton as England skipper, the comments in Jim Laker’s outspoken biography, as well as the admission that amateurs like Ted Dexter were financially doing quite well from the game. Even though the MCC were trying to keep amateurs in high profile within the game at the end of the fifties, even stalwart Yorkshire had by 1960 appointed a professional, Vic Wilson, as captain. There had been talk about compensating amateurs for ‘broken time’, although in 1958 Raman Subba Row was the first amateur to be censured for this.

As far as the match itself, a combination of dwindling attendances from a high of over 20,000, a change in the social mores, and the recognition of the lack of a distinction between amateurs and professionals in terms of their attitude to playing, meant that the fixture, standardized as two matches a year at Lord’s and Scarborough, was by 1962 of only passing interest. The MCC added some spice to the 1962 Lord’s fixture by using it as the forum to announce the team and captain for the forthcoming Ashes tour, but the Gentlemen not having won in the past 18 fixtures it was decided to up stumps and call it a day.

One Day Cricket Begins

The following year the Gillette Cup was launched, being the world’s first knock-out competition competed for by first-class teams. In the 1964 edition of Wisden, while commenting on the success of the tournament, editor Norman Preston noted that there had been calls for a knock-out competition for some years. However, a review of Preston’s editor notes from 1959-on shows no reference to this by him in Wisden, at least – in 1960, he noted that English cricket had “thrived again” during the previous summer, though in the following edition he bemoaned the falling attendance at county cricket matches (down almost 60% from the heady days of 1947), and also mentioned an MCC Committee which had been formed to look at the structure of cricket. In fact, in that same 1964 edition where he had applauded the success of the Gillette Cup, he also referenced a competition launched by the Daily Express, the Better Cricket Competition in which readers were asked to make their suggestions to improve cricket; some of these were indeed prescient, such as bonus points for faster run rates, Sunday cricket, restricted first innings, immediate admission of overseas stars to the counties, limitations on bowler run-ups and minimum over rates – clearly the spectators knew what they wanted and the game needed, even if the authorities didn’t.

In any case, it’s fair to say that the introduction of one-day cricket was not widely celebrated by the traditionalists. The title of this feature is a reference to comments in the 1974 Wisden by Gordon Ross in his piece entitled “Cricket’s Strongest Wind of Change”, in which he sniffily stated

“this type of cricket has become a family occasion; it is certainly not a connoisseur’s day. On this basis you would expect large crowds just as a Festival of Popular Music would considerably exceed a Mozart concert in attendance though the aesthetic qualities of the two types of performance would differ immeasurably in the mind’s eye of a genuine musician.”

In 1983, Wisden published an Anthology of the years 1963-1982, however editor Benny Green stated that he had included only as much one-day cricket that, in his opinion, merited inclusion, i.e. “not much”. This, despite his opening prologue including the words

“After all, argued the sophists, almost all the cricket ever played in this world has been one day cricket. Clubs everywhere have been contrasting one day cricket happily enough for centuries without ever blemishing the game or their own relish for it.”

Nevertheless, Green exhibits a little too much glee that the first ever one-day match between first-class teams, the Gillette Cup match between Lancashire and Leicestershire, was rather ironically spread over two days due to rain.

The issue of falling attendance was revisited later in the decade, when it was noted that in 1967 the total attendance at county matches was by then only half a million, or just 20% of the 1947 total. That was certainly helped a little in 1968 when overseas players were at last allowed to play county cricket without having to wait for county qualification – the likes of Garry Sobers, Rohan Kanhai, Mike Proctor, Barry Richards, Greg Chappell et al certainly made for a more exciting spectacle than previously.

However, the change which might have been the most impactful to the future of cricket was the introduction of Sunday league cricket, which began on the fledgling channel BBC2 in 1969. While the Gillette Cup was fought out over 60 overs, the John Player League featured teams locking horns for 40 overs only. Then, two years later the Benson & Hedges Cup was introduced, pitched somewhere between the existing competitions at 55 overs (later reduced to 50). In the following year’s Wisden, the editor lamented the poor state of England’s batting in the previous year’s Ashes campaign:

“The limited-over games are a worse hindrance when playing down the line is frowned upon, and even for a seasoned campaigner the long wearisome Sunday journeys on our crowded motorways and side roads, are surely no help towards freshness and eagerness to continue a three-day Championship match on Monday morning. The John Player Sunday League matches should not entail tedious travel in the midst of other engagements.”

This despite the fact that the attendance at the Sunday league matches had been almost 90% of that which the six days of county cricket could engender. Which of course was tolerated as it swelled the coffers, but it couldn’t and shouldn’t be taken seriously, thought the likes of Gordon Ross and EW Swanton, not to mention the ruling bodies.

One Day Goes International

As regards the international game, One-Day Internationals were first introduced, somewhat surprisingly, as a result of bad weather in Australia. In 1971, the Ashes Test at the MCG was rained off, following which a hastily arranged one-day match was played out over 40 overs. When the two teams next met, in 1972 in England, a three-match ODI series known as the Prudential Trophy was part of the schedule, during which series Dennis Amiss became the first player ever to score an ODI century. It would be another four years and 14 more ODIs before the first five-fer was registered, during the first ODI World Cup.

The First Prudential World Cup

There had been 18 ODIs prior to the 1975 World Cup, broken down as follows:-

MATCHES TEAM (RECORD)

15 England (7-5)

7 Australia (4-3)

7 New Zealand (1-3)

3 Pakistan (2-1)

2 West Indies (1-1)

2 India (0-2)

An excellent discussion on the First World Cup and the build-up to it can be found in Martin’s excellent piece. As can be gleaned from the discussion above, it’s fair to say that by the time of the World Cup, England players, and to a certain extent players in England, had by far more experience of one-day play than overseas players (witness Peter Parfitt’s pocket computer – Parfitt had been the first captain to note the scoring progress of the opposition and to then ensure that his team maintained at least that rate of progress, so that in the event of postponement due to rain his team would be victorious).

A look at the historical ODI ratings at that time supports this; at the end of the previous summer England was rated significantly higher than the other nations:–

RATE TEAM

114 England

97 West Indies

91 Australia

83 India

63 New Zealand

50 Pakistan

South Africa, the best team in cricket at the time, had been banished from international competition after the D’Oliviera affair and would not feature again in international cricket until 1992. West Indies had at that time only appeared in two ODIs. However two emphatic victories over England by Pakistan in August, by seven and eight wickets respectively, meant that West Indies defaulted to the top ranking, which state of affairs was maintained going into the World Cup.

Further to the previous comments on Benny Green’s proclivities as regards ODI cricket, though the annual Wisden reports did include summaries of the matches, I could find in the 1963-1982 Anthology only a very short discussion of the first World Cup from 1975, in a piece on the West Indies by Henry Blofeld.

In the tournament itself, despite their relative one-day inexperience the West Indies side held all before them in storming to the final against Australia, who had murdered England in the semi-final, and which was watched by a large crowd of 26,000 at Lord’s. India, not helped by the sluggish batting of Gavaskar in the first match against England, when he allegedly got in a net rather than chase a demanding total, finished the tournament as the lowest ranked nation. Not surprisingly, after Clive Lloyd’s Man of the Match-winning century in the final West Indies had consolidated their lead over the rest, with England by now also leap-frogged by World Cup runners-up Australia:-

RATE TEAM

128 West Indies

114 Australia

91 England

89 Pakistan

68 New Zealand

56 India

By comparison with the ODI ratings, at the beginning of 1976 the Test ratings looked like this:-

RATE TEAM

139 Australia

123 West Indies

112 Pakistan

104 England

80 India

76 New Zealand

Although the relative team positions are similar in the rankings of Tests and ODIs, the ratings totals are significantly lower for ODIs, which is partly due to the smaller number of matches played in total, but mainly due to the lower number of matches per series for ODIs as compared to Tests.

Onwards to 1979

In the four years between the 1975 World Cup and the 1979 tournament there were then 27 more ODIs played:-

MATCHES TEAM (RECORD)

17 England (9-7)

10 Australia (5-4)

10 Pakistan (3-7)

7 West Indies (5-2)

5 New Zealand (3-2)

5 India (1-4)

The relatively small number of matches played by some nations confirmed the feeling of traditionalists; as Bishen Bedi had noted “We weren’t used to the concept at all. We were brought up to believe this one-day nonsense wouldn’t last long “.

Two Men named Dennis

At this time I’d like to indulge in a small digression. As mentioned earlier, in the second ever ODI between England and Australia Dennis Amiss had become the first player to score an ODI century. In the sixth match, against New Zealand, he knocked up his second century; nobody else had managed the feat. In the match against India on the first day of competition of the first World Cup, Amiss notched up his third century, no one else had more than one at that point. And when he hit his fourth, again against Australia, only Glenn Turner could boast two, and one of those had come against an East African select team. While I appreciate that there were different levels of opportunity at that time, I’m not convinced the genius of Dennis Amiss has been adequately celebrated (except of course by our own Martin Chandler, who was privileged to co-author a piece with the great man for Masterly Batting).

Another famous Dennis recorded the first ever five-fer – Dennis Lillee took 5/34 vs Pakistan on the first day of the 1975 World Cup. By the time of Amiss’ fourth ODI ton, which was the 14th scored to that point, there had been just six ODI five-fers, which is of course much more difficult to achieve with the limited overs for each bowler than is an ODI ton. Gary Gilmour was the only bowler by then to have taken two ODI five-fers, and he also had the only six-fer, 6/14 when Australia trounced England in the 1975 World Cup semi-final.

The ODI ratings going into the second World Cup looked like this:-

RATE TEAM

121 West Indies

119 Australia

106 England

79 New Zealand

63 Pakistan

43 India

Pakistan had dropped significantly, as had India, these being the only teams with a losing record in the meantime. Once again, West Indies was looking like the team to beat and, once again, it would seem ODI experience wouldn’t be a factor.

The 1979 Prudential World Cup

The second World Cup was once again hosted by England, this time adding Sri Lanka and Canada to the six Test-playing nations. Surprisingly, Australia did not progress from the group stage – less surprisingly, neither did India. This time England made it to the final, seeing off New Zealand, but would face the mighty West Indies in her quest for glory. West Indies set a target of 287, but once England openers Geoff Boycott and Mike Brearley had dawdled to 129 in 38 overs, England effectively were lost, being then required to score at greater than seven an over for more than 20 overs. Still, the loss of the next eight wickets for just 11 runs allowed the Daily Mirror headline to proclaim “Callapso!”

By the close of the competition, twice champions West Indies had extended their lead at the top of the ODI ratings:-

RATE TEAM

142 West Indies

108 England

108 Australia

80 Pakistan

72 New Zealand

29 India

India, beaten in the tournament by non-Test playing nation Sri Lanka, had clearly not quite yet got the hang of it.

Tests vs ODIs

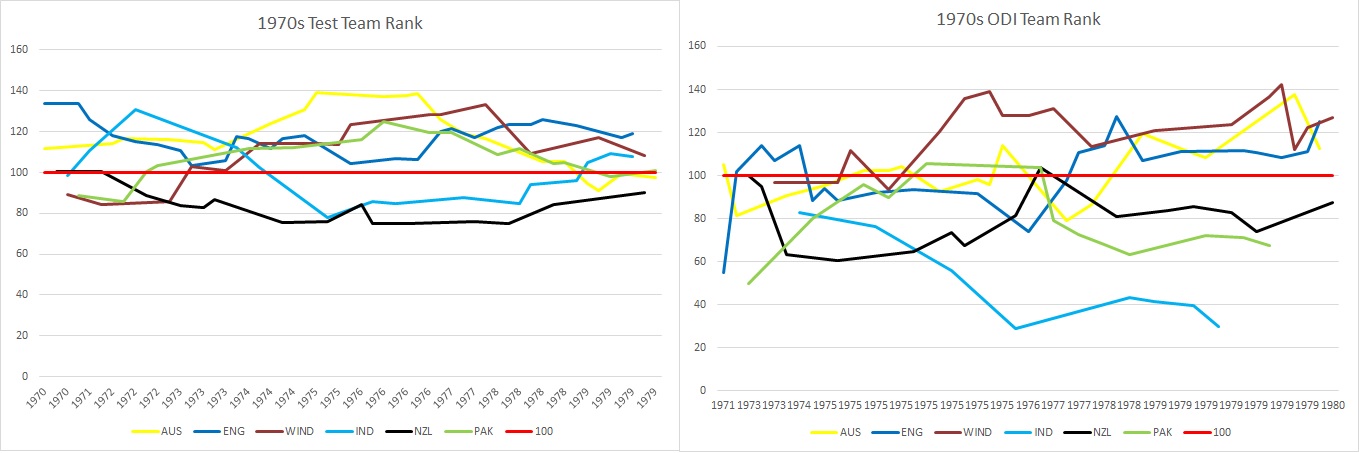

As we are now at the end of the ’70s, let’s compare the ratings of each team in both formats, something which we’ve not been able to do until now. The two profiles can be seen below side-by-side.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, we see much more variation across the teams in the ODI ratings than is apparent in the Test ratings – Test cricket had been played for 100 years by the end of the ’70s, against less than a decade for ODIs. What is also apparent in viewing the Test ratings is how the impact of the Packer schism was to close the gap between the best and worst teams as the top players went off to play in the WSC.

West Indies had surrendered her lead in the Test rankings once the Packer players were lost, overtaken by England after the 5-1 Ashes victory, though Clive Lloyd’s men would soon reclaim top spot – the late ’70s West Indies ODI team was presaging the dominance to come in Test cricket in the 1980s.

Leave a comment