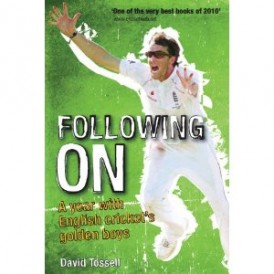

Following On

Martin Chandler |

Just occasionally a newspaper or magazine might carry an article dealing with the story of a young sportsman who has tried and failed to make a career as a professional. It is rare for full length books to dwell upon the lives and times of such players and, when they are mentioned, it is inevitably in the context of some other story, and the details will be so rudimentary as to leave the reader with no real knowledge of the individual concerned. David Tossell’s fine new book, Following On, reviewed by CricketWeb here, tells the stories of England’s most promising young cricketers of 1998. Some have been able to forge successful careers in the game and some have not. One who was unable to make the final breakthrough was Jamie Grove who had spells at Essex, Somerset and Leicestershire, before finally giving up the unequal struggle at the end of 2003 following a six year First Class career which had brought the young pace bowler 43 wickets in 25 matches at the unremarkable average of 48. David has kindly allowed us to reproduce in this feature the chapter from his book that looks at the ups and downs of Grove’s truncated career.

The village of Exning, on the western edge of Suffolk, sits a couple of well sign-posted left turns off the A14, easily located by the owner of even the most unreliable satellite navigation system. It appears that behind almost every high stone wall lining its roads is a stables or a stud farm, a reminder that Newmarket is barely a decent gallop away. Another right turn, past the equine hospital, and you come to Exning Cricket Club, who play their Two Counties Championship Division One games while grazing cows look up occasionally from an adjoining field.

Unloading his kit from the car boot, Jamie Grove explained why this season had seen him drawn to Exning from nearby Sudbury, for whom he had first played when still in short trousers. “It sounds daft, but one reason is that to get to Sudbury it is down a lot of winding roads,” he said. “Exning is a nice straight drive, which makes it much easier for me with my back, especially going home after games when I am bit stiff.”

With time to kill before play began on a late summer afternoon, Grove straddled a boundary-side bench and discussed the route that had brought him to his current cricketing home, via Essex, Somerset and Leicestershire. Any bitterness that might once have existed has subsided over time, but there was no attempt by Grove, an affable and engaging character, to hide the bemusement that has taken its place.

A chronic back condition is only one of the painful legacies of a career that began with a demand to completely remodel his bowling action and ended with death threats after a botched Twenty20 Cup semi-final. In between, there was the disappointment of missing out on the 1998 Under-19 World Cup final, a lack of consistency that he willingly owns up to, and enduring memories of bowling fast at some of the best batsmen in the game. “I loved having a brand new ball in my hand, looking down the wicket and seeing a world-class player at the other end and thinking, “Right, I have got to beat this bastard.” I always believed I could get anyone out, even if someone was hitting me for sixes and fours. It only takes one ball to get somebody out. I loved testing myself against the best players. You won some and, in my case, you lost some pretty badly.”

Born in Bury St Edmunds after his family had moved from Essex, Grove was another cricket club son, packing his kit when he went to watch his father Chris. Grove senior was a former semi-professional footballer with Dagenham who captained Sudbury and wasn’t afraid to put his son in the firing line. “I was playing from the age of three and played my first senior game for the third team when I was seven,” Grove recalled. “I think I made my debut in first-team cricket when I was 11. I got bounced first ball without a helmet. Dad would be showing us shots in the kitchen every night. If you bowled badly in a game then the meal took three or four hours. I always wanted to be an opening bowler. Even though I have always had a wiry frame I was able to bowl quick. My hero was Curtly Ambrose, simply because the guy looked evil. I was lucky enough to play against him once and it was a scary experience. I didn’t get on very well at all.

“I was at a state school, so we didn’t really play any cricket. But there was a bloke called Rob Blackmore, a farmer who made his own cricket ground, and every Monday night he had coaching sessions. I was down there from the age of five or six. Being in a minor county and not being at a public school made it a bit harder. I got five wickets and 50 runs for Suffolk in an Under-15s game and then got dropped. They brought in a nice little public school boy for the next game.” It was an early taste of the realities of team selection; a sour flavour to which Grove would become accustomed in future years.

Outside of school term-time, Grove was able to switch cricketing allegiance to the age group teams of Essex, which led to a professional contract. When he reported for his first full summer at Chelmsford’s County Ground, at the age of 16, a surprise was in store. “I used to have a perfect side-on action and was able to swing it a lot. My job was always to run up and bowl as quickly as possible and get wickets. On my first day of pre-season they completely changed my action. They made bowl front-on. That has always been a bit of a funny one with me because I had done all that work to get there. Geoff Arnold was the bowling coach and he decided it would be best. They said at some point in my career I might get back problems. To bowl front-on you need to have big shoulders. You have to be a big boy to get some pace because you are not using the twisting of the rest of your body. It changes all your bio mechanics; different angles, different stresses going through your body. I think it hindered me for a good few years and I never quite understood why they did it.

“It was a funny time trying to work out this new action. I lost my pace for three or four months. In the end you kind of work your way back to some kind of compromise. But after a few months I tore the cartilage in my left knee so I missed the rest of the season anyway. I came into my second season as a professional with an action I had never really bowled with.”

Quite apart from the reconstruction of his technique, Grove found himself stepping into a whole new world at Essex. “I had come from the background of Minor Counties and the difference was unbelievable. Our coach had been a schoolteacher who didn’t know anything about cricket but could afford the time on a Saturday afternoon to make sure everything was going smoothly. I got to Essex and there were all these coaches. My first day, I bowled for three and a half hours in the nets. It would never happen now. You get about 20 minutes. And until I did my first twelfth man duties at Essex I had never even seen a game of first-class cricket. I didn’t know who anyone was. Walking into a changing room with all these different personalities was a huge shock to the system.”

Recovered from his knee injury and playing regular second-team cricket, Grove discovered the joys of the professional game. “I absolutely loved it. We had Alan Butcher as our coach and we had a very young team. We would probably lose all but one or two games but we were playing all the 16 and 17 year olds and you were encouraged to just go out and do what you could do. It was fantastic playing on pitches where the ball actually bounced. I was bowling quicker and quicker and although people suggested things that I should do, they always said that if it was going to affect my pace I shouldn’t do it. My pace was the thing I had going for me.”

It was that speed that attracted the attention of the England management when places for the 1997-98 winter trip to South Africa were being discussed. “There were some warm-up games and we played against Scotland and a Star of India XI,” Grove remembered. “We had a big squad and I always felt confident I was going to be around there but I had a shocking game against Scotland. It was one of only two times in my life I bowled no-balls – the other was on Twenty20 finals day.”

To his relief, Grove had done enough to win selection and he duly reported to the warm-up camps at Lilleshall. “But I had a reaction with my knee after the second fitness test. It just blew up. The medical staff wanted me there but I couldn’t do anything. It wasn’t a very nice feeling because all the boys would be going off and doing their five or ten mile runs and I was just stuck with the physio. I didn’t bowl a ball until we had been on tour for a month.”

After bowling in one warm-up game in Boland, Grove was included for the second Test against South Africa, where his 13 overs produced figures of 1 for 63. “I did all right – not fantastic – but they were the flattest wickets anyone had ever seen.”

Once the World Cup games began, Grove was in and out of the side, playing in three of the six group games. His best performance was 2 for 23 in a losing cause against Bangladesh and he found himself alternating with Richard Logan for the job of sharing the new ball with Paul Franks. “Logie had a storming first few weeks of the tour. He was more of a swing bowler and I ran in and hit the pitch, so if it was a quick wicket I would play. It was back and forth and probably up until the Australia game they were still wondering where to go. Then Logie bowled really well – an awesome spell of yorkers. I knew there was no chance of playing in the final then. It hurt more missing out on the Australia game than the final. Once we were in the final then there was no one who was unhappy. We were there and had our chance to get our names in the history books. There was a great team spirit.”

Team coach John Abrahams explained, “Jamie was quick but more erratic. He was the one you would play against Namibia because he could get them out through sheer pace they wouldn’t be used to it. Later on he suffered from not playing first-team cricket. He was a confidence player. If things were going well he was good but it only took a little thing not to go well and he would focus on that.”

Grove agreed that his tour offered a window on his future years in the game. “Throughout the trip I had good spells, but I didn’t ever have what I felt was a really good game. I was slightly inconsistent and that hindered me throughout my career. I got wickets at certain times. It was a difficult tour for me. I went into it injured and had no real practice games.”

Yet there was still plenty of reason for Grove to remember the trip as one of the high points of his cricketing life. “We went to South Africa with fifteen hundred quid in our pockets, a good exchange rate, and we had a bloody good time; probably too good at times. We were living like kings. There were times when everyone wanted to kill each other, but it didn’t happen very often. If anyone was down people lifted them up. But I still don’t know how the hell we won the World Cup. We had been playing terribly, but we had some strong characters and everyone backed themselves. We knew we could beat people on our day. The biggest frustration for John Abrahams was that we had a lot people who could bat aggressively and nobody who could bat nicely for 50 overs, apart from Steve Peters in the final. It was all shit or bust, but we ended up winning games because of it. And little things like Jonny Powell’s catch against Pakistan when we were struggling changed the tournament.”

Back home in the spring of 1998, Grove was raring to go at the start of a season that would see him break into the Essex first team, taking 3 for 74 and scoring 33 runs in his first-class debut against Surrey. “By the end of the tour I’d had a fantastic time and was really fit for the start of the season. I remember my debut very well. Nasser [Hussain] gave me the new ball and Alec Stewart was at the other end. He said, “Whatever you do, don’t bowl it short and wide.” First ball, you just heard it hit the bloody advertising board. I didn’t think it was short and wide, but he managed to get a ball from off stump and absolutely blasted it for four. Surrey were the Manchester United of football and I managed to get Adam and Ben Hollioake out within a couple of balls and had Martin Bicknell caught at third man driving. I got some runs, which was quite nice, and hit Alex Tudor and Bicknell for sixes. It was good fun – the sort of thing you dream of.”

Yet Grove was never able to take enough wickets to secure his long-term future at Essex, who released him after the 1999 season. “At Essex you constantly thought you had cracked it and then you would be out of the team for what you thought was a very stupid reason. We had a pretty hard guy in Keith Fletcher as coach; a hard man and very hard to please. I was bowling quick and swinging the ball and thinking I must be part of the team. But then there is always another person trying to jump over you and Ricky Anderson came in from nowhere and got 50-odd wickets in his first season.

“And you got mixed messages. In my last year I was told, “You have got to bowl as fast as you can, but you have got to bowl line and length on off stump and you have got to swing it away.” That was pretty much what you were told every day. It was hard, to be honest. I always felt that as long as I was getting wickets, then conceding runs wasn’t a huge issue. I had always been someone who bowled five overs as quick as I could and see what happened. My biggest disappointment with Essex was at a pre-season marine training course at Dartmoor, where I sat down for a talk with Nasser and Keith Fletcher. Keith said I would be playing for England within a year; he would make sure of it. They released me at the end of the year. I played up until I got shin splints that turned into a fracture and then I got released. I saw it coming because if people stop talking to you, you know you are in trouble. I had done well in the second team but when I came into the first team I wasn’t getting much of a bowl so I was wondering whether Essex was right for me. It was a funny old club at the time. A fantastic club, but they had an old-school way of encouraging players.”

By the time Essex broke the inevitable news of Grove’s release, he knew there was a home for him at Somerset, against whom he had achieved a six-wicket haul in a second-eleven game. “It was at North Perrott, which is still the quickest track I have ever bowled on. I had just finished bowling and was fielding at square leg when I turned round and saw Kevin Shine, their bowling coach, standing next to me in the middle of a game. He offered me contract while standing there at square leg.”

A five-wicket spell in his opening first-class game for his new county suggested good things to come, but even though Grove’s career followed the same pattern of under-achievement over the next two years he looks back at his move as “the best decision I ever made”. He explained, “I lived 200 metres from the ground. I used to walk across the river to go to work and get a paper on the way. Even at Championship games you would get a few thousand people and at the one-day matches the atmosphere was unbelievable. The playing side was hard work, but a real eye-opener. You know, we had never been taught what protein was or what carbohydrates were at Essex. They were a hard run club and when you trained you did it 100 per cent, but they didn’t know about the things that could make you a little bit better. At Essex we were training really hard but no one ever really told us how to recover.”

After two seasons of being in and out of the first team, Grove was on the move again. This time he recalls it with a heavy heart. “The biggest regret I have was leaving Somerset,” he said. “I was playing all the one-day games and a few Championship games. We were second in the table in 2001 and I missed out on getting a medal by one game. I loved Championship games and didn’t really like one-day cricket. I was bowling in the indoor nets during a game against Leicestershire. I wasn’t playing and Jack Birkenshaw, the Leicester coach, was in there giving some throw downs. Jimmy Ormond was leaving Leicester the next year and Jack said, “I need an opening bowler. Are you interested?” I wanted to open the bowling and play, so everything looked good. I still had a year on my contract at Somerset, but they were really good about it. At the end of season celebrations I was thinking, “What am I doing leaving here?” But I was desperate to play four-day cricket. I moved to Leicestershire and within a few weeks they moved Birkenshaw out of the coach’s position and brought in Phil Whitticase. They didn’t see me as a Championship bowler so it ended up as a bad move.”

Grove played only two Championship games in three seasons, although in 2002 he did take 17 wickets in the Norwich Union League. “My first year went OK. I was playing under Vince Wells, who was a lovely guy, but the sad thing was all the politics at the club, which I had known only a little about. I thought players were just leaving to get more money but they lost about ten players in two years and in the end they asked Vince to leave and Phil DeFreitas took over. The less said about that the better. He decided I wasn’t the way he wanted to go. It was none of those “face fits” things with him.”

Yet Grove felt that the problems ran deeper than a personality clash with his captain. “When Jack Birkenshaw left they went from having a huge personality who was running the club, with everything done through him, to Phil as first team coach. He saw himself more as a manager and the ethos was: if you want coaching, go and ask some of the other players. I had gone from Somerset, where Kevin Shine used to organise net sessions down to the minute, to Leicester, where we had no coaching. We asked if we could get a video camera to film us and they said, “Just go out and bowl in the middle and we will turn the security camera on you.” Our bowling lessons consisted of a security camera trying to zoom in from the office and us trying to work out our actions off that.”

The breaking point for Grove, one that he is unable to forgive several years later, was the aftermath of Leicester’s appearance at the first Twenty20 Cup finals day at Trent Bridge in 2003. The Foxes were drawn to play Warwickshire, a game they eventually lost when they failed to defend a total of 162. Grove bowled only one over, a disastrous sequence that saw him go for 20 runs, including three wides and three no-balls. It could have been even worse if the free hits he allowed had been punished more severely.

“I hadn’t played for about three and a half weeks and had three epidurals in my back. I’d not even been allowed to leave my home. They let me bowl three balls the day before the finals and when we turned up it had been really dewy overnight. You couldn?t use the run-ups, so we were bowling off about three paces before play. I declared myself fit and I had an absolute nightmare.”

What happened next still shocks him. “After that game I had death threats. I had people saying they were going to rape my wife. It was all on the forum on the club website.” Other messages appeared accusing Grove of being drunk in the crowd.

“I wasn’t allowed into the ground at Leicester and they wouldn’t talk to me. I thought, “This is not for me. My wife – my girlfriend at the time – was getting abused, all over one bad game I had. Fair enough, I probably lost us the game. Twenty an over is not exactly fantastic. I know I completely screwed up. There were 20,000 people telling me that. But I’d helped get us to the bloody finals day. I went to the club office and said. “I want to call the police because I think this is terrible. But they refused to let me. In the end they said they would put a line on the website saying something like, “We fully back Jamie Grove in everything he has done and he is a professional person.” That’s all. It was not really the support I was looking for. From that point, I knew I was getting released. I was told that if I wasn’t playing then I shouldn’t go into the ground. I was having physiotherapy every day but I had to go to the physio’s clinic at half past seven in the morning to have it. That is all I was allowed to do. I felt hurt by it all. How can you not back one of your players who is trying his backside off?”

Breaking into a sardonic smile, Grove concluded, “It was slight victimisation.”

His professional career was at an end. “I was at an age where, as a fast bowler, you were expected to be winning games. And I’d had enough. I loved playing and testing myself, but all the politics involved? That is not what I do.”

Also, his back problems were getting worse, leaving with him “irritable leg syndrome”, a growth on the inside of the spine. “If I fall out of my action, it hits my nerve and my legs lose feeling. They can do an operation but there is 60 per cent chance you will end up paralysed. If I’d had physio every day I could have played professional cricket, but I was out of contract so I couldn’t afford it. I had some preliminary offers from a few clubs but in any pro sport you need to be 100 per cent in mind and body to be able to train as hard as you need. I didn’t have the drive to carry on at that point. I was time to get out there and start working.”

Grove qualified as an engineer and now works in engineering sales. Cricket is fun again, even if a few hours after reliving the ups and downs his career a last-ball loss against Ipswich and East Suffolk ended Exning’s hopes of snatching their league title. Grove took one wicket in his opening spell, but his team allowed the opposition’s last pair to score 34 to win the game. On the club’s web site a few days later, no one was being threatened.

Following On, published at a penny shy of fifteen pounds, by Pitch Publishing (www.pitchpublishing.co.uk), is available now.

My son Geoffrey Allard was picked to play for Suffolk with Jamie Grove when they where at St James Middle School in Bury St Edmunds. They were the only two boys chosen that year to play in the under Thirteens,who did not go to a public school. They also played football together. It would be lovely to get back in touch with Jamie, and his parents Chris and Pat.My other son sent me and Geoff the article about Jamie.We are sorry to hear about his back problems,and wish him well for the future.

Comment by wendy allard | 12:00am BST 5 September 2010