Deadly

Martin Chandler |

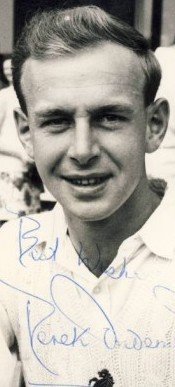

Derek Underwood was a one-off. The prime of his career coincided with my formative years as a cricket lover, and I had plenty of opportunities to watch him wheeling away with his quickish left arm spin, although in many ways he didn’t really look like a cricketer at all. His somewhat studious appearance suggested that he really ought to be a civil servant, and that a bowler hat, briefcase and ivory handled umbrella ought to be in his kit bag, rather than jockstrap, pads and batting gloves.

Deadly, as he was christened by a wise Australian, didn’t appear much more suited to his task when he got out on to the pitch. Round shouldered, and with a gait that gave the impression he had flat feet, meant that he certainly didn’t look like England’s secret weapon. Despite that, the passage of more than three decades and in spite of a valiant effort by Graham Swann, Underwood remains England’s most successful ever spin bowler, and by a comfortable margin.

As a youngster I could never quite understand why Underwood was so feared by batsmen. He looked to me like he was an inviting pace to hit, and he didn’t toss the ball up in the air – one of the first things I learnt by bitter experience was, for those with more enthusiasm than ability, how difficult that could be to bat against. But there didn’t seem to be much turn either, so I was always baffled by the enormous respect he was shown by men like Barry and Viv Richards, Greg Chappell, and particularly the superb cast of fluent, stylish and not always orthodox batsmen that Pakistan had in the 1970s, Sadiq and Mushtaq Mohammad, Majid Khan, Zaheer Abbas and Asif Iqbal.

Part of the problem was that the fairly primitive television pictures of the day didn’t really show what was going on. Underwood was no Shane Warne, in that any turn, or cut as Alec Bedser believed it was more appropriately described as, was unspectacular. The subtle variations of pace and direction were also largely lost on the younger spectator. But I still loved watching Underwood bowling for England, and seeing him tame, bewilder and frustrate the best the opposition had to offer, before administering the coup de grace.

I wasn’t so keen on watching Underwood play for Kent though. There were two reasons for that, the main one being that like almost all armchair spectators of the one day game I wanted to see runs scored, and scored quickly – these were the days when 200 in 40 overs was considered to be a big total, and niggardly bowlers liked Underwood made sure it didn’t happen too often. My other reason was rather more selfish. Kent and Lancashire were the best two sides in the country, and if Underwood was doing his usual Kent were more likely to win, and that was usually bad news for Lancastrians.

For Underwood the die was cast as soon as he was able to turn his arm over. A considerate father laid down two concrete strips in the back garden of their Kent home. Nets were erected and Underwood and his older brother were able to hone their skills for hours on end. As is the way of these things the older sibling did most of the batting, and in the absence of any fielding assistance it was entirely understandable that Underwood developed his economical action, and that he did all that he could to avoid having to do any fielding. Keeping the ball on a perfect line and length and then getting it past the bat was his aim.

After some prodigious feats in school and club cricket a 16 year old Underwood began his Kent career in 1962 with 14 second eleven matches in which he took 42 wickets. After that he never looked back and there was, in a career that stretched on for 25 more summers, just one more second team appearance.

In 1963 Underwood was handed the most difficult First Class debut possible, against the champion county, Yorkshire, on their own turf. The match was drawn, rain intervening, but Underwood dismissed five Test players for just 42 runs. He went on to finish the season with more than 100 wickets, the youngest man ever to do so.

Three years later in 1966 Underwood took 157 wickets and was top of the national averages for the first time. He also made the step up to Test level where, for the only time in his career, he must have wondered if he had bitten off more than he could chew, two appearances against Garry Sobers’ West Indians bringing him just one wicket at a cost of 172 runs.

The mauling at the hands of the men from the Caribbean did not however knock Underwood off course and he was the leading English bowler in the following season as well (he was to match that achievement once more, in 1978) and he had much more success in the two Tests he played that summer against a relatively weak Pakistan side.

Having already shown that he could run through sides, what were to remain the best figures of Underwood’s career, 9-28, were achieved against Sussex in just his second season. In 1966 he had taken 9-37 against Essex. Both of those performances were away from home and on dry and dusty pitches, so although history often creates the impression that Underwood was a one trick pony, effective only on wet or sticky wickets, that is far from the truth.

In absolute terms Underwood’s 20 wickets at 15.10 in the 1968 Ashes series were not his best series figures, but his performance in the last innings at the Oval in the final Test undoubtedly won the match and squared the series for England, and above all others is the game for which he is remembered.

England were on top throughout, and shortly before the close on the fourth day Australia started out in search of 352 for victory, just about possible but deeply improbable. When Lawry and Redpath were dismissed by David Brown and Underwood before the close with just 13 on the board, Australian ambitions were reduced to simply batting out the final day.

Early on the task seemed impossible. There was a bit of turn for Underwood, but more importantly a couple of worn areas which when, as he did at least once an over, he hit them, would cause the ball to deviate sharply. Ian Chappell was quickly undone by playing back instead of forward, and trapped lbw, before one of the worn areas caused a straight delivery to climb at and move away from Doug Walters, catching the outside edge as it did so. At 29-4 the game appeared over when John Inverarity, playing in just his second Test, was joined by Paul Sheahan. It was the 21 year old Sheahan’s ninth Test, and he was the last specialist batsman.

There was rain in the air so England attacked remorselessly, Underwood’s field consisting of seven men round the bat even then (later it would be all nine). Sheahan never looked entirely happy, but Inverarity’s solidity belied the undistinguished Test record that he ended up with (the 56 he scored here was to remain his highest Test innings). Eventually Sheahan took one too many liberty with Ray Illingworth’s off spin and was caught at mid wicket. That brought in ‘keeper Barry Jarman, and he and Inverarity were two minutes short of getting through to lunch at 86-5 when the heavens opened. At this point there were a further 210 minutes of play scheduled.

The rain did not last too long, but it was incessant whilst it fell, and there is a famous photograph in Wisden of England skipper Colin Cowdrey stood on the edge of a puddle on the outfield that looks to be at least 20 feet square. There seemed little prospect of a resumption but, with the storm gone and the assistance of fifty or so volunteers, raised from the crowd via the Oval’s public address system, the ground staff had the ground fit for play at 4.45, so seventy five minutes left. Australia were still favourites to save the game though – there was no sunshine to produce that “crust” on the surface of the pitch that gives the bowlers’ delight of a sticky wicket, and to make matters worse for England the rain had bound together the worn areas that Underwood had been able to exploit earlier in the day.

Cowdrey left Underwood on at one end and shuffled his pack from the other, but the lifeless pitch was of no help to anyone, and for forty minutes Inverarity rolled serenely on. Jarman was subjected to rather more pressure from England, and once or twice the close fielders threw themselves towards him, trying to take catches almost off the face of his bat, but whilst not looking impregnable he seemed secure enough. Taking Underwood off with just those thirty five minutes to go and replacing him with the gentle medium pace of Basil D’Oliveira might have seemed to some like Cowdrey throwing in the towel, but “Dolly” had a well earned reputation for having a golden arm, and straight away he drifted a delivery past Jarman’s bat and onto the off bail.

There was but that single over for D’Oliveira. Underwood came back and at last his skilful variations of pace, length and line bore fruit and Ashley Mallett and Garth McKenzie both played the ball into the bucket-like hands of pace bowler Brown at short leg. There were now twenty five minutes to go and England were favourites. Suddenly Inverarity started to look fallible, but the ultra attacking fields meant he could take a single without too much difficulty, and he made a good job of keeping Johnny Gleeson away from Illingworth and Underwood. Fifteen long minutes passed before Underwood got one through Gleeson’s defence and then, with just five minutes to go, Inverarity’s long vigil ended when Deadly finally managed to turn a ball past his forward defensive stroke to trap him lbw. On the page facing the picture of Cowdrey surveying the sodden outfield Wisden carries the iconic image of Inverarity’s dismissal showing, save for the square leg umpire, every man on the field.

The reputation of Underwood as a wet wicket bowler was firmly cemented in the public’s mind by the events of the Oval Test the following summer when he took 12-101 against New Zealand amidst the showers. Earlier in that series he had taken 11-70 against the same opposition, albeit not through rain. The wicket on that occasion was described as having an unusual “mottled” appearance.

When Underwood’s Test career ended at Colombo in 1982, in Sri Lanka’s inaugural Test, he had played 86 Test matches in all, and taken 297 wickets at a cost of 25.83 runs each. There had been four more ten wicket match hauls, all save one in Australia in 1974/75 with the help of the weather. There were also 17 five-fers, including one in that last hurrah in Colombo, so unlike his great rivals, India’s Bishen Bedi, Erapelli Prasanna and Bhagwat Chandrasekhar, he left the Test arena on a high. His record could and should have been even more impressive, but he missed a couple of years in the late 1970s as a consequence of joining Kerry Packer’s World Series Cricket, and as his performance in Colombo showed he was quite good enough to play on for a while longer at the end. The fact that he didn’t was not due to age (he was 35 at the time) but because he chose to visit South Africa with Graham Gooch’s rebels, the consequent ban bringing down the curtain on his England career.

In light of those statistics, and the fully deserved reverence with which he is treated in the 21st century, it will doubtless come as a surprise to many to learn that Underwood was not always treated with the same respect when he was in his prime, and that he wasn’t an automatic selection through his career. On several occasions he was dropped from the England side – did we have an abundance of riches in the spin department at the time? The answer is most certainly not, but there were those who believed they knew better than Underwood how he should bowl and perform, and therein lay the problem.

The Underwood style, as he explained in his 1975 autobiography, was of a slow medium left arm spinner. He accepted that just before he released the ball he did drag his fingers across the ball, but it is clear he did not like being described as a cutter, whether by Bedser or anyone else. He bowled round the wicket, and whilst he did turn the ball he himself accepted that his changes of pace were at least as valuable in dismissing batsman as the turn he was able to extract from the pitch. And something he did not like doing was buying his wickets. Not for Underwood was there any temptation to let the batsman have a few boundaries in order to lure him to his doom. For Underwood runs in the debit column had to be earned, and if the batsmen didn’t want to take risks then there would be a lot of maiden overs.

When 1965 arrived, Underwood’s third summer as a professional, batsmen seemed, to an extent, to have got wise to some of his ways. He tried then to slow down a bit, and experimented with bowling round the wicket, and with the umpire standing further back so he could get in closer to the stumps. He contined with the experiment the following winter on a tour to Pakistan with an MCC side led by Mike Brearley. He had a wretched time, on occasions being outbowled by the occasional spin of two of the party’s specialist batsmen, Keith Fletcher and Alan Ormrod, and he vowed that 1967 would see him revert to his original style for good.

It is against that background that Underwood so resented the attempts made to change him and made no concerted effort to do so. Bedser in particular wanted him to reduce his pace and increase his flight but he never did so, reasoning that he had tried and failed in the past. The result was that occasionally he would be left out out of the England side, but never for very long. In the early 70s the selectors flirted on occasion with Norman Gifford of Worcestershire, but in truth he was rather more like Underwood than Bedi, and was simply not as good a bowler. The selectors always returned to the Kent man in the end, but their constant carping was no doubt a factor in why such an intensely loyal and reliable man decided to take the rewards offered by WSC and South African Breweries.

An example of the sort of selectorial behaviour that frustrated Underwood came in 1971 against Pakistan. In the first Test of the three match series the visitors piled up an imposing 608-7 before Intikhab declared. Zaheer scored a delightful 274 and there were centuries for Mushtaq and Asif as well. Underwood kept his nerve and his line and bowled 41 overs for just 102 runs, but he didn’t take a wicket. He felt he had bowled well, but the selectors disagreed, and replaced him with Norman Gifford for the second Test. Back for the third Test against India after an injury to Gifford he bowled well enough to take four wickets, but was taken to task by some for failing to emulate Chandra’s magnificent performance when India chased down the 174 they needed for their first Test win in England. At least Underwood did take three second innings wickets. His fellow spinner, skipper Illingworth, went wicketless through his 36 over spell, yet oddly seemed to escape the worst of the flak.

With no winter tour for England Gifford was back for the 1972 Ashes series and played in the first three Tests. He managed just a single wicket in those games, and the unhelpful nature of the wickets is best illustrated by the fact that Illingworth only gave him 34 overs in all. So Underwood was back for the fourth Test at Headingley, and he struck lucky. A week previously the ground had been underwater, and to add to the groundsman’s woes the grass had been attacked by fusarium. In an easy England victory Underwood took 10-82. On that wicket, had he got the chance, it is unlikely that Gifford would have fared any worse.

It also grated with Underwood that when he did succeed on a helpful pitch he was given very little credit, the reasoning seeming to be that if conditions suited him there was no need for any input of skill on his part. An example was the Lord’s Test against Pakistan in 1974. The wet weather conspired to take too much time out of the game to enable England to force a victory, but also created perfect conditions for Underwood to take 13-71 against virtually the same batting line-up that all England had struggled to contain three years previously, yet his performance received no special praise.

A further aspect of Underwood’s career that he was not given proper credit for was that he succeeded everywhere he went, with the exception of the Caribbean. In India, Pakistan and Australia he turned in some excellent performances, and he tormented the New Zealanders almost as much at home in the Shaky Isles as he did in England. An apparent weakness against left handers is also overstated. The fact that like all orthodox left arm spinners he moved the ball into the southpaw rather than away is a fact of life, but with one exception he never seems to have had particular problems. That exception was the greatest of them all, Garry Sobers, and for years Sobers’s wicket eluded Underwood whether he was playing for West Indies or Nottinghamshire. The drought ended in 1973/74, the great man’s last series, and Underwood’s only one in the Caribbean. He took just 5 wickets in his four Tests, and paid 62 runs each for them, but he got Sobers twice, and two other left handers, Alvin Kallicharran and Clive Lloyd. The matchwinning performance for England in the last Test came from Tony Greig, but in the context of a match that England won by just 27 runs Underwood’s slipping one through Sobers’ defence in the home side’s second innings when he had scored just 20 was crucial.

Any essay about Derek Underwood has to mention in passing his batting. His talent in the willow wielding departent was not great, and he did not have many shots in his repertoire, but in the courage and determination stakes he would demonstrate the same qualities that characterised his bowling. His first Test saw him come in at number 11, and he contributed just 12 to a then record English last wicket partnership against West Indies of 65 with D’Oliveira. In the second innings, with England well out of the game, he was needlessly felled by a Charlie Griffith “trap door ball” which cannoned onto his face from his glove. Despite that he still became England’s nightwatchman of choice, and he was highly effective and invariably successful in that role.

Deadly never did get a test fifty, but he came close on three occasions. At the Oval in 1974 against Pakistan he came in just before the close as England set out in pursuit of Pakistan’s total of 600. It was three hours into the third day before he was dismissed for 43, having added 129 with Dennis Amiss for the second wicket. He made the same score against Australia at Sydney in the hurriedly arranged post-Packer series in 1979/80. On a sporting wicket he withstood the fierce pace of Dennis Lillee and Len Pascoe for the best part of two hours in scoring more runs in the game than any Englishman other than a 22 year old David Gower. His highest Test score 45, had come in rather different circumstances, also against Australia, back in 1968 at Headingley when he contributed 45 at not far short of a run a minute to a last wicket partnership of 61 with Brown. The game was drawn easily enough in the end, but there might have been a tough fight for England without that contribution.

There are those who say that the mark of a top class batsman is one whose Test career average exceeds his overall First Class average, and if so perhaps Underwood is the exception that proves the rule. He was also unusual in that his best season with the bat, and by a distance, came in 1984 when the 39 year old amazed everyone by making a maiden First Class century. He went in as nightwatchman at number three in his side’s second innings against Sussex at Hastings, where twenty years previously he had recorded his career best bowling figures. He scored more runs himself (111) than the entire Kent side had in their first innings (92), and a remarkable match ended, fittingly, as a tie. As well as his best batting and bowling performances Underwood also produced his most spectacular figures at Hastings, 8-9 in 1973.

Derek Underwood left the game at the end of the 1987 season, thus just missing the introduction of four day cricket in the County Championship, something that his bowling was ideally suited for. He wasn’t, in spin bowling terms, a thing of beauty, in the way that the Holy Trinity were, but he was every bit as good a bowler as any of them. I know now, having seen nothing like him in thirty years, that we didn’t realise quite how special he was at the time, and if I could bring one man from my time as a cricket lover forward in time to the present day England side, whilst it would be tempting to nominate Botham, Flintoff, Gower or Gooch, I suspect the man who would strengthen side the most would be Derek Underwood, even though he would never see a rain-affected pitch.

Lovely and informative piece, Fred.

Comment by zaremba | 12:00am BST 27 June 2014

I still don’t know how Deadly did it, but give him a rain affected pitch and he was truly unplayable.

Comment by John | 12:00am BST 20 July 2014