Creepy

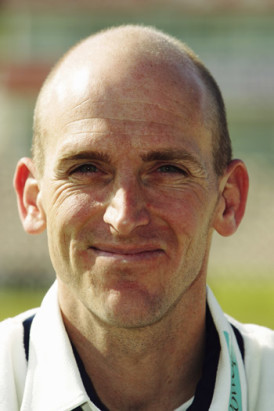

Martin Chandler |

John Crawley, known affectionately throughout his career by one of the better sportsman’s nicknames, Creepy, was one of English cricket’s three nearly men of the 1990s. Like Graeme Hick and Mark Ramprakash Crawley was in and out of the England side for almost ten years. Had he been born a decade or so later and played sooner than he did under the more enlightened regime of Duncan Fletcher he might well have achieved a great deal more at international level.

There will be some who will disagree. Crawley’s detractors always highlight the fact that he was a poor player when bowlers made him play on the off side, unable to score quickly and rendered almost strokeless until an inability to be absolutely sure where his off stump was saw him dismissed. That is a harsh judgment. The truth is that he was a quite brilliant batsman against bowling directed towards his legs. The fact that he didn’t show the same mastery on the other side of the wicket meant he was not destined to be one of the greats, but it certainly didn’t make him a poor batsman.

In much the same way Crawley was a most accomplished player of spin bowling. That did not, of course, ipso facto make him a poor player of fast bowling. To listen to some commentators however you could be forgiven for believing it did. There was a bit more merit in the suggestion that Crawley did not look like an international sportsman. Early in his Test career he was somewhat overweight, and was both a drinker and a smoker. But after his first trip to Australia in 1994/95 Crawley lost all the surplus timber, and his previously less than impressive fielding improved markedly.

Crawley was the youngest of three brothers who all played First Class cricket. Eldest brother Mark played for Oxford University and for four seasons with Nottinghamshire without quite establishing himself. Middle brother Peter did not play county cricket, but did play four times under John’s captaincy at Cambridge.

After breaking most of Michael Atherton’s records at Manchester Grammar School Crawley was handed a Lancashire debut against Zimbabwe as an 18 year old in 1990. He made an unbeaten 76 in the second innings. For the next three summers the county had to share him with Cambridge University. He looked assured right from the start and if there were ever any doubts the 109 he scored from the opening slot to guide the Red Rose in a successful pursuit of a victory target of 227 set by the touring Australians in 1993 dispelled them. Neither Tim May or Shane Warne, nor Merv Hughes, held any terrors for Crawley and after a successful winter with England A in South Africa no one was surprised when he was called up for his Test debut against the full might of the Proteas the following summer. Crawley played in all three Tests, but his only score of any substance was 38. The visitors did not play a spinner all series, and a quality pace attack comprising Alan Donald, Fanie De Villiers, Brian McMillan and Craig Matthews was sufficiently well briefed to give Crawley nothing to feed his strengths.

Despite his disappointing start against South Africa Crawley had done enough to secure a place in the party that went to Australia in 1994/95 under Mike Atherton. Not much was expected of England who quickly, without Crawley, went 2-0 down. For the third Test he was recalled for the first of many times and scored 72 in England’s only innings as they went on to set up what might have been a winning position, and which certainly resulted in them having the better of a draw. They went one better at Adelaide and won to give themselves something to fight for in the final Test.

After a nightmare in the first three Tests the veteran Mike Gatting came good in the England first innings with a final Test century and Crawley contributed 28 to a total of 353. Australia took a first innings lead but England managed to set them a target of 263. Graham Thorpe and Phil De Freitas scored 80s but the glue that held England’s innings together was Crawley’s three hour vigil for 71. Australia should have been capable of chasing that 263 for victory in 67 overs against England’s injury ravaged side, but they collapsed to 83-8 before Ian Healy and Damien Fleming finally showed some application. Australia were 35 deliveries away from safety when their final wicket fell.

Stung by their defeat Australia roared back at Perth and won by 329 runs. Crawley wasn’t alone amongst the Englishmen in having a nightmare, but his was the worst, a seven delivery pair combining with a torrid time in the field. It was no surprise when he did not line up against the West Indies in the first Test of the 1995 summer.

Whilst Crawley’s reputation will always be that of a man most at home against spin bowling he certainly did not lack ability, application and courage against the fast men, qualities best illustrated by an innings which, by virtue of its modesty, is never going to be obvious from the record books. The event was the fourth Test of that 1995 series against West Indies, and Crawley’s recall after his pair at Perth. The men from the Caribbean, no longer invincible but still a strong side, were 2-1 up and fighting hard to hang on to the Wisden Trophy.

The match was at Old Trafford and England secured a first innings lead of 221 with just Crawley of the specialist batsmen failing to get into double figures. Brian Lara set about demolishing that lead in the way that only he could but with little support from the middle order, and in the face of some fine bowling by Dominic Cork which included a hat trick, England’s victory target was just 94. A formality, or so we England supporters thought. Unfortunately for our heart rates however Courtney Walsh, Curtley Ambrose, Ian Bishop and Kenny Benjamin weren’t about to cave in. Mike Atherton and Nick Knight put on 39 for the opening partnership and when they were parted Crawley came to the wicket. Fifty minutes later England were 48-4, effectively 5 as a lifter from Walsh had fractured Robin Smith’s cheek.

There followed a most difficult hour. The West Indians bowled like the great champions they were whilst Crawley got solidly behind everything and Jack Russell batted with the sort of unorthodoxy that only he could, and in the end England got home without further loss. Crawley’s contribution was as valuable a 15 as has ever been scored in Test cricket. The two sides having got each other’s measure the final two Tests were drawn, Crawley’s only contribution of any substance being exactly 50 in the first innings at the Oval. It was enough to get him on the winter tour to South Africa but not to retain his Test place. He played in just the third match of the series when, the fourth and fifth days being washed out, he did not even get to the crease.

Recall number four for Crawley came the following summer against Pakistan, England’s opponents in the second half of the season. He played in the second and third Tests, a draw and a defeat for England, but it did look like Crawley may finally have arrived. He scored an attractive 53 in the second Test and then in the losing cause a maiden century, 106, described by Wisden as majestic.

Next on England’s agenda was their inaugural Test against Zimbabwe. Crawley scored another century as a match that meandered along unconvincingly to start with ended in thrilling fashion as the first Test in history to be drawn with the scores level. In the second Test, and the series that followed in New Zealand Crawley got several starts without making another big score, and then it was Australia again. Crawley played in the first five of the six Tests but was dropped for the last. He contributed just a single to England’s remarkable and unexpected triumph in the first Test and by the time he recorded scores of 83 and 72 in the second innings of the third and fourth Tests England were well on the way to heavy defeats.

This time Crawley’s time in the international wilderness was as short as it could be, just a single match. He was selected to tour the Caribbean that winter and was back for the first Test. He held his place for the next two as well but his highest score was just 22, and once again that was that. This time the absence was slightly longer as Crawley missed the whole of the home series against South Africa. He took the opportunity instead to have a magnificent summer for Lancashire. His tally of runs was more than twice that of the next man and, by the end of the season and a one off Test against Sri Lanka, he had earned recall six. In a match that Sri Lanka won to record their first victory in England, thanks to a match haul of sixteen wickets from Muttiah Muralitharan, Crawley was unbeaten at the end of England’s first innings on 156. It would remain the highest of his four Test centuries, but it would never have happened if Murali had not overstepped in his first delivery to Crawley, and the gentle return catch the mercurial Sri Lankan snapped up had counted.

Crawley’s fifth successive England tour followed as he visited Australia for the second time in 1998/99. He had a thoroughly miserable time, the tone for his tour set early on when, in Cairns, he was attacked on his way back to the team hotel at night and suffered some facial injuries. Once the Tests arrived he was left out of the side for the first Test, as was Graeme Hick, thus England went into the Test with neither of the centurions from their previous outing being selected despite both being available. Crawley was back for the second and third Tests, dropped for the fourth and brought back for the fifth. In six innings he scored just 86 runs at an average of 14.33. It was a measure of England’s misery that despite that there were still only five men above him in the England averages. One who he bested was county colleague and former skipper Atherton.

Crawley succeeded Wasim Akram as Lancashire skipper for the 1999 season. It was a good summer for the Red Rose as they finished as runners up in the County Championship. Winning the 40 over National League as well made up for a lack of success in the cup competitions that Lancashire had done so well in over the years. For Crawley there was no distraction from England, although with just 870 he scored less than half of the runs he had the previous summer. By way of consolation he did have his best ever season for Lancashire in List A games.

Coming as it did in the last season of the old century, that performance in the first summer of the new millennium brought a surge of optimism throughout the county after the appointment of former Australian skipper Bob Simpson as coach. Simpson, together with Allan Border, had transformed the Australian Test side and all Lancastrians dared to hope that he would do just as well with Crawley at restoring the Red Rose to the glories of the 1930s when another Australian, fast bowler Ted McDonald, was primarily responsible for a hat trick of Championship titles.

In the event it was a season of marking time. Lancashire were runners up in the main event again, but there were two cup semi-finals, although neither opportunity to get to Lord’s was taken. Failure and relegation in the National League were however disappointing, particularly coming straight after taking the title.

Simpson’s second summer with the club was a grim one from a Lancashire point of view. Relegation from the first division of the Championship was avoided only on the last day of the season. There was no progress beyond the group stage of the Benson and Hedges Cup and no promotion back to the top tier of the National League. In the flagship one-day cup, now sponsored by Cheltenham and Gloucester, there was a semi final, but it was a dark day. Lancashire slipped to 60-6 at one stage, and although there was then a recovery the bowlers could not prevent Leicestershire, with a 21 year old Shahid Afridi leading from the front, romping home with more than 20 overs to spare.

Having signed a two year contract with the club there was much speculation as to whether Simpson’s contract would be renewed. Crawley had hoped that the Australian was in for the long haul, and it was certainly a blow to him when Simpson decided to announce his resignation at the beginning of August, a few days before the Leicestershire match.

As for Crawley he had signed a new four year contract shortly before Simpson’s resignation, but even then there was a good deal of strain on the relationship between captain and coach on the one hand and Chairman Jack Simmons and the county committee on the other. The first serious crack opened up during the semi-final Crawley being understandably angry when committee man and former England seamer Paul Allott, wearing his Sky Sports commentator’s hat, openly criticised Crawley’s captaincy as the defeat unfolded. Later, during an end of season National League match against Derbyshire Simmons was said, whilst in the press box, to have been openly critical of Crawley, indeed one report uses the word ‘abusive’

Earlier in the summer the committee had not been happy about the team management’s decision to leave out of the Championship side two of Lancashire’s most popular players. All-rounder Ian Austin was 35, and had taken a lucrative benefit in 2000 that netted him £155,000. For Graham Lloyd, son of Bumble, 2001 was his benefit season and the 32 year old raised £170,000, but he played only three First Class fixtures. His age suggested there should still have been plenty of cricket left in Lloyd, but although he got a few games in 2002 under new skipper Warren Hegg he did not achieve a great deal, thus indicating Crawley and Simpson’s judgment was sound.

After Simpson’s resignation Crawley was told he would not be required as captain for the following season, although Lancashire remained keen to retain his services as a batsman. This was hardly surprising. He had not been able to repeat his magnificent form of 1998 but despite the cares of the captaincy Crawley had remained one of the county’s few reliable batsmen and his talent remained clear for all to see.

From Crawley’s point of view however he saw no future with the Red Rose. He formally asked the county to be released from his contract, a request which was quickly denied. Fairly early on in the dispute it was reported in the press that Hampshire were prepared to offer a three year contract so, if Lancashire refused a release, Crawley had to either sit out his contract or take to the courts to, effectively, claim constructive dismissal. ECB rules contained a very similar provision, one which allowed a player to terminate his contract if the county was found to be guilty of serious or persistent breach of the terms and conditions.

Problems where feelings run high have a tendency to become magnified and intractable once lawyers become involved and that was certainly the case here. Crawley chose to engage the country’s then highest profile employment lawyer, Cherie Blair QC. The first move those advising Crawley took was to put the matter before the England and Wales Cricket Board’s Contracts Appeals Panel, and a hearing was fixed for 15 February 2002. The Board decided in favour of the county, but Crawley announced his resignation anyway, stating that he was no longer a Lancashire player, and adding that coach Mike Watkinson, a former teammate at Old Trafford and with England, had in any event told him not to attend any training sessions involving the playing staff.

Behind the scenes the lawyers were still active and, thankfully, a deal was brokered that enabled Crawley to resume his playing career. A statement issued by the club confirmed that following a period of contract negotiations the club has agreed to release John from his contract upon the payment to the club by him and Hampshire County Cricket Club Limited of a suitable five figure compensation payment. The exact details of the agreement were the subject of joint confidentiality obligations, but the figure is thought to have been around £35,000. Together with whatever part of that compensation fell upon him personally Crawley had to bear his own legal fees, reportedly of the order of £16,000, and he also had to forego the prospect of a benefit in 2003 which, as a Test player would surely have exceeded those of Lloyd and Austin. Whatever the rights and wrongs of the matter those financial sacrifices display as starkly as anything just how deeply hurt and let down Crawley must have felt.

The Lancashire statement did at least add the club wish to place on record their thanks to John for his 12 years of service to the county. In all First Class matches Crawley scored more than 10,000 runs for Lancashire at an average of more than 50. He wasn’t quite so effective in List A matches, but almost 5,000 runs at more than 30 was a more than useful contribution. I and every other Lancashire supporter I knew were very sorry to see him leave for pastures new.

There had been no place in an England side for Crawley since the final Test of the 1998/99 series so Hampshire Chairman Rod Bransgrove, who had first met Crawley back in 1994/95 in Australia, must have been counting on a full season from his man. In the event it was not to be. Clearly Hampshire expected runs from their new signing, but a betting man would have got long odds on Crawley getting as many as 272 in his first innings for his new county, and when he did the 30 year old once again caught the selectors attention. A Sri Lankan attack deprived by injury of the talismanic Murali were his opponents. Against expectations the visitors secured a comfortable draw. Crawley scored 31 and 41* but he was the only one of England’s six specialist batsmen not to score a half century so, with Alec Stewart and Andrew Flintoff at seven and eight it was Crawley who made way for the extra bowler the selectors decided, rightly as it turned out, was required for the next Test.

Gone maybe, but not forgotten. Crawley was back a couple of months later and, for what was to prove the only time he was to do so, played through an entire home series. Innings of 64 and 100* were a significant factor in England securing only their second win against India in the previous dozen years. He was out after making a start on each of the other four occasions he got to the crease without going past 26, but it was enough to get him out to Australia for his third attempt at what was then the most difficult mission in world cricket.

The 2002/03 Ashes were a familiar story. Australia won the first three Tests at a canter. In the fourth they became a little complacent and managed to lose five wickets in reaching a victory target of 106 before, not for the first time, allowing England to win a meaningless final Test. Michael Vaughan had a magnificent series but, a fluent unbeaten 69 in the first innings of the first Test apart Crawley did not achieve a great deal in the three Tests in which he played. At least this time he was not dropped, injury making him unavailable for the second and third Tests, but that was the end. He had been dropped by England for the tenth and last time.

Persuaded to take on the Hampshire captaincy for 2003, pending the hoped for appointment of Shane Warne for 2004, neither Crawley nor the county enjoyed a good summer. For the first time Crawley failed to make a century in a full season and he averaged just 33.76. It was hardly surprising the selectors looked elsewhere. The following season would have been similar, had it not have been for the game against Nottinghamshire at Trent Bridge. When he made that 272 on debut Crawley cannot have imagined that it would be more than two years before he tonned up for Hampshire again, or that when he did so he would surpass his first effort. That both sides scored more than 600 says all that needs to be said of the state of the wicket, but an unbeaten 301 certainly boosted Crawley’s figures for the season.

In 2005 it was more of the same albeit Crawley did manage three centuries – Nottinghamshire must have grown heartily sick of him however as, in the last Championship match of the summer, he made an unbeaten 311 against them. Critics would point out that nothing turned on the match, Nottinghamshire having already won the title and resting three key players including their leading bowlers Mark Ealham and Ryan Sidebottom. Crawley was given a life on 28 as well, but it could never be said he was not a man to exploit good conditions when he found them, the innings being his seventh in excess of 250.

Perhaps it was that innings that inspired Crawley to spend the following winter working on his technique. That it was time well spent was amply demonstrated as he rolled back the years in 2006. In 16 appearances there were more than 1,700 runs, six centuries, and seven more innings of over 50 for an average of 66.80. Wisden described it as a summer of glorious achievement. There was talk of an England recall and a fourth Ashes trip. In a clever double bluff Shane Warne put the mockers on that one by declaring Crawley the best player of spin in England, and that he should be a certainty for selection. Those charged with the task of choosing the party fell for it and, remembering many previous instances of Australians trying to secure the selection of Englishmen ill-equipped for the task ahead, Crawley was left out. They had another chance to pick Crawley when Marcus Trescothick pulled out, but went for Ed Joyce instead. They should have listened to Warnie, as the memory of that dreadful 5-0 thrashing reminds us.

There were three more summers for Crawley before retirement. He never shone so brightly again as in 2006, but he did pretty well in 2007. The following year was his benefit year. Hampshire no longer publish accounts for beneficiaries but he will not have got as much as he would have got had he stayed with Lancashire, and he would have had his benefit a good deal sooner at Old Trafford. In 2009 Crawley announced that he did not wish to stand in the way of Hampshire’s younger batsmen and retired. He went into teaching and coaching, first at Marlborough College, then Magdalen College Oxford after which he returned to the Public Schools, firstly with Oakham followed by his current position at Oundle.

Leave a comment