Compo

Martin Chandler |

If the good doctor’s biographer is to be believed WG Grace was the most recognisable man in Victorian England, challenged for that position only by four time Prime Minister William Gladstone. In an age before Television, Radio or Cinema, and when newspapers and magazines were sparsely illustrated, that was a remarkable achievement for a sportsman, and it must surely be certain that no other cricketer will be quite so famous again. Occasionally some have briefly held the entire nation in thrall, Sir Ian Botham in 1981 and Andrew Flintoff in 2005 being the most obvious examples, but their tenure on the front pages has never been lengthy. In truth only Denis Compton can compare with the game’s “Grand Old Man”.

Grace was a fine athlete in his youth, as well as a cricketer. Botham played a bit of professional football, albeit for lowly Scunthorpe United, and Flintoff has dabbled in the boxing ring. Denis Compton on the other hand was not only one of the finest English cricketers of his time, but he was also a gifted footballer. In those days soccer was a very different game to the one that today’s Premier League stars play, but then as now it was the forward players who won most of the plaudits, particularly from the neutrals, and Compo played on the left wing, and was renowned for the sort of mazy runs and pinpoint crosses that all wingers in those days aimed to produce. He wasn’t quite as good as the “wizard of dribble” himself, the legendary Stanley Matthews, and he never played for England in a full international, but he surely would have had Matthews not been in his way.

Circumstances conspired to ensure that Compo’s football career was limited. He was never a first team regular for Arsenal, and played just 60 games all told with 16 goals to show for it, but those figures tell only a small part of the story. In 1938, when he was just 20, Compo suffered the knee injury that was to dog him for the rest of his life and adversely affect his performances in both sports. The incident itself was a collision with Charlton Athletic’s goalkeeper, although whether it was their first choice, Sam Bartram in a First Division game, or Bartram’s understudy Sid Hobbins in a reserve team game was, in years to come, to confuse even Compo himself. At various times Compo said it was both of them, but diligent research subsequently established that there was an occasion when he was left hobbling after a collision with Bartram, but that there was also a game in which he had had to be stretchered off after falling over a diving Hobbins.

Compo was 21 when the 1939/40 season was suspended and he then missed six more seasons during which he would have been in his prime. In 120 appearances for Arsenal in war-time games he scored 74 goals, and appeared for England in a dozen unofficial fixtures. After the war cricket took centre stage, so due to MCC tours his only full seasons were 1947/48 and 1949/50. In the former he appeared 14 times as Arsenal took the old First Division title, and his last game for the club was the FA Cup Final in the latter season. He famously had a dreadful first half but, substitutes not being allowed in those days, he had to carry on. The truth is that he was a stone or so overweight for top class football, and the size of the playing area at the old Wembley had meant that he was simply out of breath most of the time, but thanks to a pep talk from the manager, and a tot of brandy from Alex James, a hero of the great Arsenal side of the 1930s, he was a different player in the second half and made a very real contribution to the acquisition of the winner’s medal that he picked up later that afternoon.

But it is as a cricketer that Compton made his greatest mark, and he is remembered today for his prowess as a batsman. He lacked the steely determination of a Herbert Sutcliffe, the classic orthodoxy of his peer Len Hutton, or the ruthless efficiency of a Bradman, but in some ways he had very much more than any of them. Colin Cowdrey described him as .. a particular hero of mine from when I first lifted a cricket bat, but coaches always used to stress, “enjoy watching him but don’t try to play like him”. The sentiment was echoed by author Jeffrey Archer when he said Denis inspired an entire generation of schoolboys to pick up a cricket bat. Compo’s Middlesex colleague Fred Titmus was once asked by Michael Atherton how good Compo was, and his response was as graphic a summary as any; I can’t tell you that Mike, because you just wouldn’t believe me.

So what was there in this not to be imitated technique? The reality of course is that it was based on solid principles, a good eye and nimble footwork. But Compo didn’t always bother to get his foot too close to the pitch of the ball when driving, and the 2lb 2oz wand that he used was frequently not straight. The sweep to leg, played to deliveries of varying pace, length, line and direction was the shot for which he was most famous, but he was a master of the cut, pull and hook as well.

Compton’s personality was also a factor in both his cricket and his popularity. He was never troubled by nerves, not infrequently having to be woken up when it was his turn to bat. On debut, at 18 in 1936, he batted at number eleven and batted well before getting an lbw decision from an umpire who needed to close the innings in order to get to the pavilion to relieve himself. In the next game, against Nottinghamshire, he was promoted to number eight. Harold Larwood was not as quick as he had once been, but still faster than anything Compo had faced before, and he finished that season top of the First Class averages with 119 wickets at less than 13 runs apiece. Larwood was not happy when the youngster drove him for four twice in quick succession, and even more displeased when his riposte, a bouncer of course, was hooked to the boundary as well. An angry “Lol” wanted to teach the youg tyro a lesson, but deprived himself of the chance by promptly ripping out the last three batsmen in rapid succession to leave Compton unbeaten.

By the end of 1936 the 18 year old Compo had become the youngest man to score a thousand runs in his debut season. He had been seriously considered for a trip to Australia with Gubby Allen’s side that winter but the final view taken by Allen, who effectively had the casting vote, was that he was too young and an early introduction to the strongest side in the world might damage his prospects. It seems difficult to believe that it would have done and, given the disappointing performances of a number of the batsmen who did make the trip, there is a strong case to be argued that he might have made all the difference between Australia retaining the Ashes and Allen emulating Douglas Jardine’s feat of four years earlier in retaking them. As time passed Allen certainly accepted that a mistake had been made.

There was not long to wait for Compton’s Test debut though as he carried on the 1937 season where he had left off the previous summer and was selected for the third and final Test against the touring New Zealanders. He came in at number four in his only innings and scored a typically entertaining 65 in just two hours before he was unluckily run out. His partner in a stand of 125, Joe Hardstaff, drove one of Giff Vivian’s slow left arm deliveries straight back at him, and when he could only deflect the ball onto the stumps he caught Compo out of his ground, backing up too far.

It is impossible to write about Compton without the subject of his running between the wickets cropping up. Although statistics indicate that he was actually run out less frequently than the norm* the anecdotal evidence against him on that score is overwhelming, the oft-quoted warning being that when Compo called for a run it was “merely a basis for negotiation”. Stories abound of his disasters, all met by a sheepish grin from the culprit when they were put to him. In 1954 he managed to run out his brother Leslie (also Middlesex, Arsenal and England although his international caps came on the football field) for a duck in his benefit match, and then ran out two more as well. But at least he went on to play an innings that guaranteed a good turnout for the third and final day and, as always, the combination of his talent and personal charm meant that nobody was annoyed with him for very long.

The following season was an Ashes year and 20 year old Compton scored a century, 102, in his first innings against Australia, and he played in all the Tests that summer and the next against West Indies. Arsenal stopped him touring South Africa in 1938/39 and after that it was Hitler who put the mockers on the next six years during which Compton, not yet unduly troubled by his knee, would surely have been at his peak. As it was the massive boom in spectator numbers that greeted the return of peace-time conditions in 1946 meant that millions were to see him in his full glory for four summers, and it was during the late 1940s that Compo cemented his place in the nation’s affections.

The annus mirabilis was 1947. After a dreadfully harsh winter the sun seemed to shine every day and nowhere more so than wherever Compton and Middlesex were playing cricket. Page 174 of the 1948 edition of Wisden was fascinating to me as a child. It contains a list of Compton’s 18 centuries that summer, followed by the 12 of Bill Edrich, and the 12 scored by Jack Robertson, Middlesex men the three of them. All told Compo scored 3,816 runs at 92.32. A strong South African side were comfortably defeated, and Compo took four centuries from them in the Tests, and averaged 94.12 for the series. In the final match of the season he scored 246 in the then traditional Champion County versus the Rest of England fixture which, for once, the Champions won at a canter.

Naturally the heights of 1947 could not be scaled again but, until the knee surgery of 1950 that brought an end to Compo’s salad days, he remained at the top of his game. In 1948 Bradman’s Invincibles heavily defeated England and simply crushed most of the other opposition that came their way. In the first Test Australia won comfortably by 8 wickets, but in the second innings Compo scored a superb 184 to at least take the game into a fifth day. Then at Old Trafford he played what is probably his most famous innings and one which, had rain not intervened, might just have resulted in an England victory. Coming in at 33-2 after England skipper Norman Yardley had won the toss and elected to bat on a wicket that was far from good, Compo was, after scoring just 4, forced to retire hurt after receiving a sickening blow on the head from a Lindwall bumper. The wound duly stitched he returned to the fray at 119-5, and was undefeated on 145 when the last wicket fell with the total on 363. No one else scored more than Alec Bedser’s 37.

In reply Australia conceded a first innings deficit of 141 and by the close of the third day England had extended their lead to 315. Sadly however the Manchester weather did not treat the game kindly and the fourth day was washed out. Yardley declared first thing on the last morning but, just two and a half hours play being possible, the game petered out into a tame draw.

Having been denied the opportunity to tour South Africa ten years previously Arsenal did not stand in Compton’s way again in 1948/49 when he enjoyed a successful tour, averaging over 50 in the Tests and 84 in the First Class matches as a whole. His tour included his only triple hundred, exactly 300 against North Eastern Transvaal, an extraordinary innings that contained 198 in boundaries and took him just a minute over three hours. It was during this series that Compo took his only five wicket haul in Tests. It would be stretching a point to describe him as a genuine all-rounder, but a career haul of more than 600 First Class wickets at only 32 runs apiece is eminently respectable, particularly for a bowler of Compo’s type. He begun at Middlesex as an orthodox left arm spinner, but when his batting talent began to blossom he gave that up in favour of the dark art of left arm wrist spin. Always self-deprecating his explanation for the wickets he took was that he was sometimes able to bowl batsmen out when they dithered about whether to hit him for four or six. In truth of course he was a decent bowler, but the five-for was the more impressive because he did not bowl his wrist spin. England had two specialist leg spinners in their side, but the lack of a finger spinning option at Newlands looked problematic as the South African off spinners, Athol Rowan and Martin Hanley, put England under the cosh in their first innings of 308, and when the South African reply got to within ten runs of England with just two wickets down the situation looked bleak. But Compo warmed to his task and once he finally broke through the last eight wickets went down for just 58 and the match was easily drawn.

In 1950 Compo was 32 and the knee required surgery again (a first operation in 1947 had alleviated the symptoms but not cured the problem), causing him to miss half the season. He did enough to convince the selectors of his fitness for the 1950/51 Ashes tour, but then endured what must be the leanest time ever experienced by a batsman of his quality. He played in four of the five Tests, but averaged just 7. His knee was far from perfect, but he scored plenty of runs outside the Tests and indeed averaged more than 50 for the tour as a whole so neither the disability, nor the well publicised breakdown of his first marriage, could have been the root cause of his poor showing in the Tests.

Compo the great was never quite as great again after his operation, but there were still another 35 Tests to go. In 1953 he had a disappointing Ashes series as England finally regained the urn. There were just a couple of fifties but, fittingly, it was Compo who scored the winning runs, whilst he was at the crease with his “twin” Bill Edrich. In 1954 he recorded his highest ever Test score, 278 in just 290 minutes, against Pakistan. That winter he went under the surgeon’s knife again and was late joining England in Australia. Having arrived via a flight that had to crash land in Pakistan, there was further misfortune for Compo as he broke a finger whilst fielding in Australia’s huge first innings, and he had to bat almost one-handed at the end of England’s innings for 2* and 0 as they subsided to an innings defeat. As he missed the second Test and scored 4 and 23 in the third it seemed for a time that on a personal level the trip might be little better than the previous visit until his 44 and 34* proved crucial in the series-clinching victory in the fourth Test, and his 84 at Sydney helped England to a winning position there after rain had wiped out the first three days.

It was almost back to business as usual against South Africa in 1955, with Compo averaging more than 50, but his mobility was clearly restricted. In 1956, whilst Jim Laker was mesmerising Australia the “Compton knee” prevented its owner’s season beginning until the end of June. Having resumed his career he did enough to earn a recall for the final Test, his last at home. He came in at 66-3 with England in some peril. He helped his captain, Peter May, rebuild the innings by scoring 94 out of their partnership of 156, and there was much sadness at the Oval as he was dismissed as close of play approached and missed out on what would have been a hugely emotional century.

That winter Compo toured South Africa for the second time and played his final Tests. He did just enough to hold his place throughout the series, but averaged just 24 and was a shadow of his former self. Back home in 1957, his last full season, he did reasonably well for Middlesex, and scored his thousand runs for the seventeenth and last time but he, as did all his legion of fans, saw the writing on the wall.

In 1958 Compo joined the BBC and added commentating to the Daily Express column to which he had lent his name since 1950. He developed a pleasant and laconic style at the microphone, which certainly brought pleasure to younger viewers, but he was no great analyst, and was seldom critical of that vast majority of players whose gifts were less extravagant than his own. As the 1960s wore on an issue arose which, for the first time, dented his popularity. He was an outspoken critic of the decision to sever sporting links with South Africa. He was no supporter of apartheid, and was incapable of prejudice, but equally unable to grasp why sportsmen could not pursue their ambitions in a bubble, free from political considerations and interference. In time most understood that Compo’s views were solely as a result of his deep love for the game, and indeed all sport, but for a time he attracted considerable criticism.

As for his private life Compo married for the first time during the war, to a very attractive young dancer, Doris. The couple had one son, Brian, but as noted the marriage did not last and the couple divorced. Compo met his second wife, Valerie, in South Africa in 1948/49. Again the marriage failed, the second Mrs Compton not being able to settle in England. Compo enjoyed his time in South Africa but could not bring himself to leave England so, reluctantly, he acquiesced in Valerie’s return to the country of her birth, with the couple’s two sons, Patrick and Richard. Compo was 54 when he married for a third time in 1972. Christine, who he had first met in her capacity as Bagenal Harvey’s PA, bore him two daughters, the younger of whom was born as long as twelve years into the marriage.

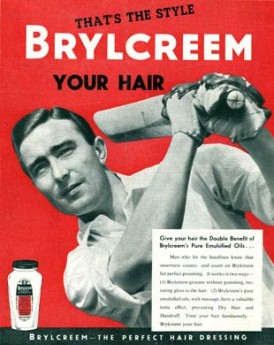

When Compton met Bagenal Harvey the latter was involved mainly in publishing. He was a good friend of journalist Reg Hayter, a man who resembled Compo sufficiently to on occasion be mistaken for the master batsmen, including at least once when Hayter found, as a consequence, a naked woman climbing into the bed in his hotel room. Compton had, in the late 1940s, taken Hayter into his confidence and shown him a suitcase stuffed full of unopened letters. Hayter promised Compo he would sort them out and tried to do so. He found the usual “fan” letters displaying various degrees of infatuation from sundry men and women, but also the odd cheque and large numbers of offers of work. Hayter passed the huge task to Harvey who became the first sporting agent and who swiftly negotiated Compo’s famous contract with Brylcreem, nine years at GBP1,000 per year. It was a huge sum, and other endorsements soon followed as did Harvey’s withdrawal from all his other business activities so that he could concentrate on Compo, and the succession of leading sportsmen that subsequently sought his assistance.

Denis Compton died, perhaps appropriately for a great Englishman, on St George’s Day 1997. He was 78 and had been ill for some time. The defining moment in his passing came on 1st July when a service of thanksgiving for his life was held at Westminster Abbey. Two thousand managed to get tickets to attend, and there were hundreds more outside. All of the great and the good from the cricket world attended, but it was not just a cricketing event, and well known people from many walks of life were present, but one particular pair above all others best expressed the priceless ability of men like Denis Compton to unite and give pleasure to everyone who watched them. The first was John Major, who had been the Conservative Prime Minister up until a few months before, a lifelong cricket lover whose politics would doubtless have struck a chord with Compo. He gave up the opportunity to attend at the ceremony to mark the handing over of Hong Kong in order to join in the celebration of Compo’s life. The second, at the other end of the political spectrum, was the “Beast of Bolsover”, Dennis Skinner, still in Parliament today at the age of 80 and probably the last real socialist left in the Labour Party. He said afterwards, He was a real adventurer. He took risks and went for runs right from the off. He was everything that Boycott wasn’t.

It is sometimes said, usually by those who fail to match parental sporting prowess or expectation, that talent skips a generation, although the sporting fate of Compo’s sons does lend some credence to the idea. Brian, eldest and photographed as a toddler so often with his father with a bat in his hand, did not aspire to the First Class game at all. In South Africa both Patrick and Richard did, but with just a handful of appearances for Natal between them neither made a great impression. But we do of course have a new Compton playing for England now. Richard’s 29 year old son Nick is currently Alistair Cook’s opening partner and, while in need of a decent score soon a first nine Tests that has included two centuries has been a decent start to an international career. For those of us who love the five-day game there is something compelling about watching Nick Compton, but I think we can be certain that in forty years time Joss Butler will not be having the same exchange with England’s then captain that Fred Titmus had with Michael Atherton twenty years ago.

*Compton was run out just 26 times in his First Class career, or 3.46% of his dismissals. I know not the figures for First Class cricket as a whole but Dave Wilson tells me that in the history of Test cricket 3.51% of all wickets have been run outs. Over the period of Compo’s career that figure is a little higher 3.70%, and isolating his run outs in Tests gives Compo a percentage of just 2.78. Given that he was such a bad judge of a run this can only demonstrate the willingness of his partners to sacrifice their own wickets when he made a bad call something which, to me, is simply evidence of how much his peers felt the need to preserve his wicket rather than their own (ie what a good batsman he was), and the degree of unselfishness that he inspired (ie what a popular bloke he was).

Great article. What a player, and such elan about him.

It’s great the player of the Ashes series gets the Compton-Miller award. They were two of a kind in the way they went about it.

Comment by Burgey | 12:00am BST 27 May 2013

Top quality stuff, fred.

That’s a, er, beast of a quote from Skinner too. 😎

Comment by BoyBrumby | 12:00am BST 28 May 2013

A big hero of my dad’s, and of a man I used to work with, both of whom were born around 1930 and the ideal age for idolising him in those postwar years. I remember that Titmus quote, it was in his [I]Wisden[/I] obituary in 1998. EW Swanton paid a nice tribute as well: “I doubt if any game at any period has thrown up anyone to match his popular appeal in the England of 1947 to 1949.”

Comment by stumpski | 12:00am BST 28 May 2013

Great read as always.

Comment by Coronis | 12:00am BST 28 May 2013