Colin Ingleby-McKenzie – A Life Well Lived

Martin Chandler |

Colin Ingleby-McKenzie was the last of his line, that of the roistering, carousing amateur who managed to play the game of cricket to a high standard and, whilst burning the candle at both ends as well as in the middle, earn almost universal respect and admiration as captain of a county side.

Ingleby-McKenzie came from a naval background, his father being a Surgeon Officer who eventually rose to the rank of Vice-Admiral. The inevitable consequence was that the young Ingleby-McKenzie led a peripatetic existence before attending Ludgrove Preparatory School in Berkshire from the age of eight. To illustrate the sort of people he was always at ease with the Duke of Kent was one of his contemporaries there.

The headmaster at Ludgrove was Alan Barber who before going into teaching had enjoyed two productive seasons as an amateur batsman for Yorkshire. Ingleby-McKenzie was already a fine cricketer even at that tender age and was marked down by Barber and Hampshire men Harry Altham and Desmond Eagar as one to watch.

At thirteen Ingleby-McKenzie moved on to Eton College, then as now one of the most prestigious, if not the most prestigious of the English Public Schools. It is clear from his 1961 autobiography that the occasional privations that pupils had to undergo held no terrors for Ingleby-McKenzie, who in time was elected President of the Eton Society, also known as Pop, a group of senior pupils who traditionally enjoy special privileges.

After leaving Eton in the summer of 1951 Ingleby-McKenzie made his First Class debut for Hampshire. The game was seriously interrupted by rain and there was not even time to complete the Hampshire first innings. Ingleby-McKenzie did get to the crease but, perhaps surprisingly in view of his extrovert character, admitted to being extremely nervous. His first delivery was every debutants dream, a full toss from Sussex off spinner Alan Oakman. He could do no more than block the ball. The next delivery pitched and knocked back the middle stump and that was that.

Never a great scholar, he was far too interested in playing sport, Ingleby-McKenzie nonetheless surprised himself by passing the necessary examinations to read history at Trinity College Oxford, his father’s alma mater. In the end he didn’t go, preferring to accept an offer of employment with Slazenger. It seems an odd decision for a sportsman who so enjoyed his social life to give University a miss in the 1950s, but the only explanation he gave was that, having decided he wanted to work in the city, it was as well to start at the bottom three years earlier than studying for a degree would have permitted.

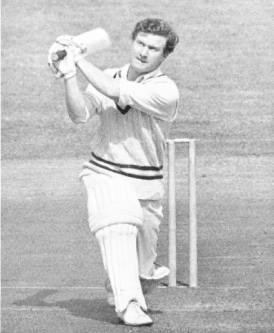

As a cricketer Ingleby-McKenzie was a batsman. His entire First Class bowling career consisted of just fifty wicketless deliveries, so he was not even an occasional off spinner. He did keep wicket sometimes, but with just one stumping to his credit in 343 matches was clearly no expert. With the bat Ingleby-McKenzie was an entertainer. He was a left hander and finding a photograph of him at the crease doing anything other than playing the slog sweep for which he became famous is no easy task. The numbers are nothing special as an average of 24.35 amply demonstrates, but then Ingleby-McKenzie never played for himself. Above all he was an exceptionally good captain.

In January 1952 Ingleby-McKenzie began his national service, and unsurprisingly chose the Royal Navy. It must be unlikely that he expected that his father’s rank would make his life any easier, but he would have been disappointed if he did. His basic training, as for every one else, was in a barracks in Portsmouth, and involved much washing up and toilet cleaning – there was no fagging in the Navy.

At least in Portsmouth Ingleby-McKenzie had a few opportunities to play for Hampshire and he did much better than on debut, averaging almost thirty over his seven games, and there were three half centuries including 91 against the touring Indians. There was less cricket the following summer, just two First Class appearances, but Midshipman Ingleby-McKenzie did appear against the touring Australians. The visitors won at a canter, Keith Miller and Jim De Courcey both posting double centuries, but the Services went down with all guns blazing, Ingleby-McKenzie top scoring in their second innings with a rapid 66.

His national service over Ingleby-McKenzie was back with Slazenger in 1954 and, as would be expected from a sporting goods manufacturer, they allowed Ingleby-Mackenzie to play a full summer’s cricket for Hampshire. It wasn’t a successful season, as he averaged just 17.84. The man himself offered no excuses, although Wisden did, explaining that the soft pitches in a damp summer did not suit his game. The following summer Slazenger were rather keener on getting some work out of their man, so he played just once for Hampshire, called in to keep wicket when first choice Leo Harrison was picked to play for the Players against the Gentlemen.

Despite his commitments to his employers there were still plenty of opportunities for Ingleby-McKenzie to play cricket. His outgoing personality and love of a good time made him a popular tourist, and he went on a number of private trips. Twice he went to West Indies with strong sides raised by EW ‘Jim’ Swanton and he accompanied Swanton once to India and the Far East as well. He captained a Commonwealth side to East Africa. With the MCC he was a member of parties that visited South America and East Africa and, as late as 1981, by which time Ingleby-McKenzie was 48, Singapore.

It is clear from everything written by and about Ingleby-McKenzie that a great passion in his life was the turf. He tells the story in his autobiography of a largely unsuccessful attempt to get to a race meeting at Fontwell Park whilst at Eton, but the fact that he only managed to get there towards the end of the meeting seems not to have dampened his enthusiasm. Betting on the horses is a constantly recurring them throughout the book and whilst there is no balance sheet the impression is certainly created that Ingleby-McKenzie knew what he was doing, and that he won at least as often as he lost.

Many who have written of Ingleby-McKenzie have gone as far as to suggest that he would on occasions deliberately miss matches which coincided with important race meetings. Having read John Arlott on Ingleby-McKenzie, and no one of his era knew the county as intimately as Arlott, it is apparent that in rapid succession there were genuine injuries that coincided with Royal Ascot and ‘Glorious’ Goodwood, so hardly surprising the recuperating cricketer was to be seen in the enclosures. That said Ingleby-McKenzie was always happy to tease those who interviewed him despite not fully understanding the game, so he may well have contributed to that particular belief. What is certainly true is that he often spent time during breaks in play speaking to his bookmaker on the telephone, and at least one umpire was persuaded to take a radio out to the middle with him so that Ingleby-McKenzie could listen to an important race.

In 1956 Ingleby-McKenzie was available more often for Hampshire and he scored his first two centuries, the first against Oxford University in the Parks, and the other, rather more impressively against Worcestershire. By the following season, after ten years in the job, long time skipper Eagar was looking to retire from the game and with Ingleby-McKenzie the man in waiting Slazenger were persuaded to allow him to play for the whole summer, during which he deputised for Eagar on a number of occasions. He passed a thousand runs for the first time, and most certainly looked the part.

The 1957 season saw Hampshire finish 13th in the Championship table as Surrey swept to victory for the sixth successive time. The following summer that immensely powerful Surrey side made it seven out of seven, but they so nearly failed. In a decidedly damp summer Ingleby-McKenzie’s Hampshire led the table for much of the summer and had it not been for a disappointing conclusion to the season that saw them win just one of their last eight matches the Championship pennant would have flown at Northlands Road in Southampton.

In West Indian Roy Marshall Hampshire had one of the most attractive and reliable batsmen in the game, and in Derek Shackleton the perfect bowler to exploit the damp conditions. For Ingleby-McKenzie it was a case of aggression all the way, both in his captaincy and with the bat. Despite the conditions he made his thousand runs again. There were two centuries both, at the time they were scored, being the fastest of the season to that date and the quicker one, in 61 minutes, after having got to the ground without having gone to bed the previous evening. All in all it was disappointing for Hampshire to be runners-up, but that was still their best finish ever and at the end of the season Ingleby-McKenzie was named as the Cricket Writers Club Young Cricketer of the Year.

The south coast crowds were happy too, The Cricketer noting at the beginning of the following summer that the desire for Ingleby-McKenzie’s brand of cricket resulted in vastly increased attendances. There was even some talk of the Hampshire skipper making the trip to Australia with Peter May’s 1958/59 side, but it seems unlikely he was seriously considered. Certainly Ingleby-McKenzie himself always said he was nowhere near good enough for the Test arena

There was however one major change for Ingleby-McKenzie that winter as he decided to leave Slazenger, although it must have been an amicable parting as he continued to represent them on a freelance basis. His new employment was with an insurance brokerage, to whom he was introduced by former Kent skipper Bryan Valentine. The relationship of master and servant got off on very much the wrong foot, Ingleby-McKenzie wandering into the office for the first time six weeks after he was due to. A difficult meeting with senior management followed, which only got easier as Ingleby-McKenzie shared with those sitting in judgment on him the names of a number of winners for that afternoon’s card at Kempton Park.

The following summer saw Ingleby-McKenzie score more than 1,600 runs, by some distance his highest tally ever, but Hampshire slipped to eighth, and in 1960 to twelfth. Too many of the gambles didn’t quite come off, and Lady Luck was too often elsewhere, but writer AA Thomson, a Yorkshireman, described Ingleby-McKenzie as the cavalier of the cavaliers and the dasher of the dashers before adding there ought to be more like him.

There was an experimental law in county cricket in 1961 as the follow on was suspended. The key to victory was suddenly much more dependent on skilful timing of declarations. Hampshire won nineteen times in the Championship, on ten occasions as a result of their opponents failing to reach targets that Ingleby-McKenzie had set. Only twice did Hampshire fail to win after a declaration, and on neither occasion did they lose, Middlesex and Northamptonshire holding on for draws. It is said that it was Ingleby-McKenzie’s knowledge of odds (from his racing) and risk (from his insurance work) that was the key. It helped that so many others beside Marshall and Shackleton were able to step up to the plate. Batsmen Henry Horton and Jimmy Gray both topped 2,000 runs, and Shackleton had the support of a genuine fast bowler, David ‘Butch’ White who took more than a hundred wickets.

When the main men failed there were still more heroes waiting in the wings, not least the skipper himself, who almost singlehandedly won the match against Essex at Cowes on the Isle of Wight. In 1956, the first time the county played at the ground owned by the local shipbuilders, Ingleby-McKenzie had scored 130 against Worcestershire and in 1961 he scored an unbeaten 132 there, which would remain his highest ever score. In the Hampshire second innings Ingleby-McKenzie came to the crease at 35-4. His side had two hours fifty minutes in which to survive or score 206. They got there with a quarter of an hour to spare and with four wickets in hand Ingleby-McKenzie playing with, in Wisden’s words, the utmost confidence and power. Come September Hampshire had seen off the challenges of Middlesex and Yorkshire, and for only the fifth time since 1890 a side from outside the ‘Big Six’ of county cricket had taken the title.

It was during that 1961 season that Ingleby-McKenzie gave the television interview that is considered to define him. In response to the question ‘To what do you attribute Hampshire’s success?’ he responded ‘Oh, wine women and song I should say’. The follow up question was ‘Do you have certain rules and discipline, and helpful hints for the younger viewer?’ with the straight faced retort ‘Well, everyone in bed in time for breakfast I suppose’. The interviewer for Junior Sportsview didn’t have a clue about the game and entirely in character Ingleby-McKenzie saw an opportunity to make mischief, but for most that is an irrelevant detail given that his flippant answers really would not, in reality, be so very far from the truth.

As the 1962 season dawned there seemed to be no reason why Hampshire should not be contenders for the Championship once again but it was not to be. Ingleby-McKenzie remained at the helm until the end of the 1965 campaign but the county finished 10th, 10th, 12th and 12th. There were a variety of factors at work, and Ingleby-McKenzie’s haul of runs gradually fell so that in 1965 he scored a modest 684. Perhaps more surprising was that Hampshire’s record in the early years of the first limited overs competition, the Gillette Cup. Only once between 1963 and 1965 did Ingleby-McKenzie’s men defeat First Class opposition.

His cricket career over at 32 Ingleby-McKenzie was at last able to concentrate on matters of insurance. Without a family background in the business, and lacking an impressive academic record there might have been some expecting him to fail. If so they were completely wrong. Ingleby-McKenzie’s main talent was, of course, as a bon viveur and a magnet for potential clients, but he cannot have risen to be Chairman of Holmwoods without having a thorough understanding of the insurance business. When in 1992 he successfully led a £33 million management buy out of the brokerage from its holding company he proved his entrepreneurial credentials as well. Those were reinforced three years later when HSBC took over, Ingleby-McKenzie making a handsome profit as well as negotiating the position of Deputy Chairman of the Bank’s insurance division for himself.

Most modern articles about Ingleby-McKenzie, and almost all of his obituarists, make reference to his being one of the last people to see Lord Lucan alive. The story has slipped into obscurity now but was a great English cause celebre of the 1970s. The 7th Earl of Lucan, a contemporary of Ingleby-McKenzie’s at Eton, disappeared on 8 November 1974. The previous evening the Earl, an inveterate gambler who generally played at the prestigious Clermont Club in London and who was locked in bitter divorce proceedings, had visited his former matrimonial home and, mistakenly, murdered his children’s nanny. The actual target was the Countess of Lucan, but she was able to flee to a local pub before the Earl could take her life as well.

Lucan disappeared the next day, and despite many purported sightings and all manner of theories as to his whereabouts he has never been found, dead or alive. It is difficult to find a source for the assertion the obituarists make. The two full length accounts of the affair that I have read make no mention of Ingleby-McKenzie at all, and it seems that Ingleby-McKenzie himself was the source of the story. Many years later, after he chose to make some comments about Lucan the Countess rounded on Ingleby-Mackenzie and asserted that the pair did not know each other well, and were only really linked by occasionally playing golf together. Quite where the truth lies will almost certainly never now be known, but I suspect there is little in the story. What undoubtedly is true however is that Ingleby-McKenzie was extremely well connected and completely at ease in the company of the aristocracy, the celebrated and the rich and powerful.

On a personal level Ingleby-McKenzie’s enormous appetite for the single life precluded marriage for many years, but he was finally ‘caught’ in 1975 by divorcee Susan Stormonth-Darling, known as ‘Storms’. The couple had a daughter of their own to add to the three sons and a daughter Storms had from her first marriage.

Once his workload at HSBC reduced Ingleby-McKenzie took on the task of cricket manager for the wealthy cricket loving philanthropist Sir Paul Getty. Between 1996 and 1998 he was President of the MCC. The club is not, of course, always noted for its dynamism, but Ingleby-McKenzie presided over a period of great upheaval. First of all there was the new media centre, which was approved during his tenure. More dramatically the club finally agreed to admit women as members, a change that had long been resisted but for which Ingleby-McKenzie had actively campaigned. Celebrating the decision Ingleby-Mackenzie made the splendid if somewhat politically incorrect comment, women are a very fine species. It was undoubtedly a good thing that an aside to former England and Glamorgan skipper Tony Lewis did not reach such a wide audience. After the first ten ladies received their memberships Ingleby-McKenzie whispered to Lewis perhaps we should have inspected the merchandise first.

Advancing years do not seem to have slowed Ingleby-McKenzie to any great extent. In 2000 he became the captain of Sunningdale Golf Club, and in 2002 the president of Hampshire. A lasting tribute to the first man to lead them to the County Championship is the Colin Ingleby-Mackenzie stand at the Ageas Bowl. In 2005, a year in which Ingleby-McKenzie was awarded the OBE, he was present at Lord’s in September to help Hampshire celebrate lifting the Cheltenham and Gloucester Trophy. Sadly it was a last hurrah as a few weeks later a malignant brain tumour was diagnosed, and the condition claimed Ingleby-Mackenzie on 9 March 2006. He was 74.

It was inevitable after the abolition of the distinction between amateur and professional that the traditional gentleman amateur had had his day, but by then Ingleby-McKenzie, with his oft quoted mantra of entertain or perish was already a throwback to a bygone age. Perhaps surprisingly in view of his background he seems to have been almost universally liked and respected, the only person I have found who has uttered any real criticism being the Countess of Lucan.

Leave a comment