Charles Townsend: A Forgotten Hero of the Golden Age

Martin Chandler |

All-rounder Charles Townsend made his First Class debut for Gloucestershire as a 16 year old in 1893. In 1899 his remarkable achievements earned him his two Ashes Tests. There were no Test matches played in 1900, when Townsend enjoyed another good summer, but that was it. After that Townsend chose to concentrate on establishing his career in the legal profession, and although it would be as late as 1922 before he played his last First Class match from 1901 on he was only ever an occasional member of the Gloucestershire side.

Townsend’s father Frank was a county stalwart who played for Gloucestershire between 1870 and 1891. WG Grace’s description of him as dashing a batsman as I ever saw may be clouded somewhat by the friendship that the pair enjoyed, but clearly shows there was cricketing talent in the family. Two of Frank’s other sons (he had eight children altogether), Frank Junior and Miles also played for Gloucestershire, but both on just a handful of occasions. Charles, whose godfather WG was, was undoubtedly the most talented member of the family.

Frank Senior was a headmaster so, like his sons after him, played as an amateur and means were such that the young Townsends had a coconut matting wicket in their garden at home, and a net to protect the house itself from flying cricket balls.

The three years that Townsend spent at the prestigious Clifton College were ones of conspicuous success on the cricket field, and it was after he finished the second of those summers, 1893, that he was called into the county side for the match against Middlesex on his home wicket at Clifton. Despite the presence of WG the hosts lost the game by an innings and 98 runs, and from five in the order Townsend contributed just a single run in each innings. But he had been selected primarily as a bowler and the callow youth (Townsend was close to six feet in height but barely ten stone in weight) opened the bowling and was called upon to bowl as many as 70 five ball overs, ending up with the creditable figures of 3 for 151.

Appearing in all of the county’s four remaining First Class fixtures that summer Townsend soon slipped down the batting order, and had just 28 runs to show for his efforts, but he also had 21 wickets at 21.51, including 5-70 against the touring Australians, and his best figures were 6-56 against Surrey. In only his second First Class match, against local rivals Somerset, Townsend performed the hat trick, remarkably all three batsmen being stumped.

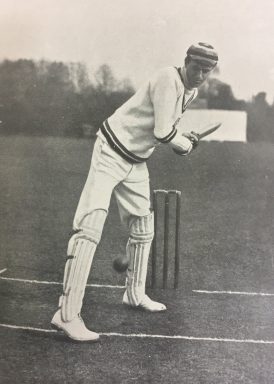

So what sort of bowler was Townsend? Cricketarchive and all the books indicate, not terribly helpfully, simply that he was a leg spinner. In 1899 WG wrote that he bowls over the wicket, with a high right hand delivery, and sends down a fast medium ball with a deceptive leg break ……he puts in an occasional fast ball. Years later another teammate, Gilbert Jessop, commented in his autobiography that I can recall no leg break bowler of his pace, excepting Braund, being so accurate in length, nor one whose bowling came so quickly off the pitch. His pace through the air was too fast to allow a batsman to jump out to him with any great hope of success. It is also clear that Townsend could also make the ball break in to the right hander so, this being a decade before the googly was introduced to the game, he must have slipped in the occasional break as well.

Townsend left Clifton in 1894 so once more joined the county in August. His batting made limited progress until, in an end of season festival match, he scored 79 for the West against the East at Portsmouth. His bowling was once more his strong suit, his 37 wickets costing him 23.89 runs each.

It was during the summer of 1895 that Townsend really made his name. Once more with the bat there was a modest improvement, but certainly not as much as was doubtless hoped for after Townsend’s first appearance of the summer, against Somerset at Bristol in May. In reply to Somerset’s 303 Gloucestershire slipped to 15-2 to bring Townsend to the crease to join his godfather, who had started the match with a total of 99 First Class hundreds to his name. WG went on to make his hundredth hundred, and on his way to a huge 288 he added 223 with Townsend, who was dismissed just five runs short of his own century.

After the Somerset match Townsend did not reappear in the county side until the end of July, but once he did his bowling was spectacular. In a total of just 14 matches his season’s haul was 131 wickets at 13.94, 94 of them in August. Wisden’s verdict on those figures was that this bare record, splendid though it is, does not convey any idea of the brilliant character of his work before, after conceding that he had found some helpful wickets along the way, it was astonishing that a bowler not yet 19 years of age should so thoroughly prove the master of the most experienced batsmen in the country. The view of Jessop was that on that season’s form….. Charlie Townsend will always appear to me as the greatest slow bowler on all wickets of my time.

In fact Townsend’s record was not sufficient to see him finish at the top of the First Class averages, that honour being taken by the occasional Hampshire pace bowler Coote Hedley whose 48 wickets cost him fractionally less, but the more telling statistic was, perhaps, that of all the country’s leading bowlers Townsend’s strike rate, at just over 27, was the best of them.

In 1896 the Australians came to England and, on the basis he continued with the form he had shown the previous summer, Townsend would surely have been called up by England. In the final analysis however whilst the first season for which he was available to play all summer showed a reasonable return Townsend’s form in May, June and July being patchy to say the least, a Test call eluded him. With the bat Townsend, as he had the previous summer, averaged a tick over 20 and had four half centuries the highest of which, 96 for the Gentlemen against the Players at the Oval just overhauled his previous high score.

With the ball there were 113 wickets for Townsend at 22.19 in 1896, the majority of them in the latter part of the season. According to Wisden early on he had suffered from an affectation of the arm, similar to but not, apparently, tennis elbow.

The following season of 1897 gave no opportunity for Test honours, and again there were mixed fortunes for Townsend with bat and ball. With the ball he was Gloucestershire’s leading wicket taker with 92, but he paid as many as 27.33 runs for each of them and no fewer than five of his teammates had better averages, including the 49 year old WG. This time round however injury seems not to have been the problem, Wisden’s report on the season indicating that Townsend’s accuracy had suffered, and whilst in those days some bowlers suffered from problems caused by poor fielding the Almanack specifically ruled that one out, making the point that Townsend was fortunate to have been as well supported as he was.

As far as his batting was concerned the bare numbers suggest that Townsend marked time, as a slight fall in his aggregate was offset by a similarly marginal rise in his average. In truth however there were distinct signs of progress. The elusive first century came, and an impressive one it was too, 109 against Yorkshire in their own backyard in Harrogate as Gloucestershire enjoyed a rare away win over the White Rose. In the opinion of Wisden however his best performance was a week before the Yorkshire game, when an unbeaten 67 skilfully guided Gloucestershire home against Notts with five minutes and three wickets to spare.

Still only 21 in 1898 Townsend reassured his supporters that summer that not only was his batting star on the rise, but that he could bowl as well as ever. With the ball he took what was to remain his best haul of wickets, 145, at a much improved average of 20.64. Once again he showed a particular liking for late season wickets, the final five matches of the summer bringing him as many as 65 of those victims at just 11 runs apiece. It was during this purple patch that he recorded what were to reman his best figures, 9-48 against Middlesex at Bristol as the side who were to end the season as runners up in the Championship were shot out for 75.

With the bat Townsend made a giant step forward and, according to Wisden, had a justifiable claim to being the best left handed batsman in the country. One of just three men to do the double that summer (Yorkshire’s Stanley Jackson and Lancashire’s Willis Cuttell were the others) all told he scored 1,270 runs at an average of 34.32 and in doing so recorded five centuries. Perhaps oddly the bulk of his runs came in the early part of the season when his bowling was less effective, and vice versa.

The peak was 1899. Townsend enjoyed a magnificent summer in his penultimate season as a regular First Class cricketer. He all but doubled his run tally which rose to 2,440 and only Ranji and the Surrey pair of Tom Hayward and Bobby Abel scored more. Townsend finished seventh in the First Class averages on 51.91 and no one exceeded his tally of nine centuries. With the ball he was less impressive, but still did the double for the second and final time, his 101 wickets costing him a relatively pricy 29.06.

The Australians were in England in 1899 and it was no surprise when, after the drawn first Test, Townsend was called up for the second match at Lord’s. Sadly for England the game ended in a hugely disappointing 10 wicket defeat and Townsend’s scores were 5 and 8. Picked primarily for the runs he might score his three wickets in the Australian first innings were scant consolation, and as England drew the third and fourth Tests Townsend was back in Gloucestershire’s colours.

A recall was, as Townsend’s batting continued to sparkle, always on the cards and he duly got the nod for the final Test at the Oval. England won the toss and batted and, just before the close and with his side well placed on 428-4, Townsend came to the crease. He survived that tricky period and next day took his score to 38. Australia were made to follow on but England couldn’t bowl them out twice and the game was drawn and the series lost. It is perhaps a measure of the lack of importance attached to Townsend’s bowling by this time that across the two Australian innings he bowled just 13 economical but wicketless overs.

Having now fulfilled expectations of his batting it is worth pausing briefly to consider what sort of batsman Townsend was, and again I will quote WG and Jessop. In the words of his god father Townsend can hit hard, though he generally plays a steady consistent game. His long reach permits him to play forward easily, and he drives with exceptional cleanness, a view confirmed by Jessop who wrote of him, although he had the usual left-handers punch past extra cover, he relied in the main for his runs by deflecting the ball.

The close of the English summer of 1899 saw Townsend undertaking his only significant overseas tour. A strong team was put together under Ranji’s captaincy to tour North America for three weeks in September and October. After his efforts in the English summer Townsend’s contributions with both bat and ball were modest even though the opposition was distinctly lacking in quality.

The first year of the new century was a strange one for Gloucestershire in that the county was without WG, still a useful batsman as well as the county’s talisman, his having fallen out with the committee in taking up an offer from the Crystal Palace to run the London County side. Without WG Townsend was, in the words of Wisden, nothing like as fine a cricketer as in the previous season. His contributions with the bat were still good, 1,662 runs at 34.62, but he again lost accuracy with the ball and accordingly was not used as much as in the past, and a fairly modest 57 wickets cost almost 29 runs each.

Although his father had been to University, in his case Trinity College Dublin, when Townsend was interviewed by Cricket: A Weekly Record of the Game in 1895 he was clear that he did not intend to pursue a university degree himself. It is perhaps surprising that the interviewer did not then go on to ask him about his ambitions for the future, or perhaps he did and Townsend had not (he was only 18 at the time) made any plans. In any event the choice Townsend did make was the legal profession and once he qualified as a solicitor he relocated to Stockton-on-Tees in order to practice law. In time he served also as an Official Receiver, and his cricket was largely confined to the North Yorkshire and Durham League. Interestingly despite having been brought up in an area where League cricket was unknown Townsend did become an advocate of League structures for club cricket.

Despite moving as far from Gloucestershire as he did Townsend nonetheless preserved his links with the county and there were occasional appearances each year until 1907. Despite playing so irregularly there were still some notable appearances, most particularly an innings of 147 against Sussex in the second of his three matches in 1902. With a couple of wickets in each innings to go with the century it was an impressive performance from a man who by then was essentially a club cricketer.

Four years later in 1906 Townsend was able to appear twice for his county, and in the first of those matches, against neighbours Worcestershire, he produced a batting display that Jessop was moved to describe as astonishingly brilliant. Townsend made the second highest score of his career, 214, and Jessop added his off driving was a revelation to me, for I had never before seen him hit with so much force.

And that still was not quite the last time that Townsend stunned the cricket world. After the appearance against Worcestershire he played in the next match against Yorkshire, and then against the White Rose again in 1907, finding three spare days to travel the relatively short distance to Harrogate and the scene of his first century. He didn’t quite reprise that memorable innings and on this occasion Yorkshire won easily enough but Townsend did top score with 61 in the Gloucestershire first innings.

Following that outing in Harrogate it was a full two years before Townsend ventured on to a First Class field again, appearing for Gloucestershire against the Australians at Cheltenham in 1909. The Australians had already won the five Test series 2-1 and had beaten Gloucestershire by an innings earlier in the tour. Gloucestershire were having a wretched summer and would finish at the bottom of the Championship, and their skipper and best player, Jessop, was missing.

Against that background in agreeing to skipper his old county Townsend must have wondered if he had selected a poisoned chalice, but the Australians under estimated their opponents. They began by resting all of skipper Monty Noble, Warwick Armstrong and Frank Laver, although even when they were all out for 211 after winning the toss and choosing to bat they must have still felt they had enough. If they did they were certainly wrong as the home side’s response was 411, skipper Townsend coming in at first drop and making 129 in just two hours, batting as he had against Worcestershire two years previously. Sadly for Townsend there was not enough time left in the game to force a win, but Gloucestershire ended what must have been a morale boosting draw well on top.

Following that match against the Australians Townsend turned out in the next game, against Worcestershire and after that just once more before the Great War, a forgettable defeat at the hands of Yorkshire in 1912. When peace returned Townsend was 42, and had not played regular cricket for twenty years, but he still had one more eye-catching performance to produce amongst his ten First Class appearance between 1919 and 1922. All were for Gloucestershire, one against the Australian Imperial Forces XI in 1919 and, in each of the following three summers, three Championship matches for the county at the end July and beginning of August. In those there was a half century against the AIF, and another in Townsend’s very last appearance against Essex at Leyton in 1922.

The game that deserves a slightly lengthier mention was played in 1920 at the Fry’s Ground in Bristol against local rivals Somerset. The visitors won the toss and would doubtless not have been overly happy with their all out first innings total of 169. The mood in the dressing room later that day would however have been very different, as Gloucestershire in turn were bundled out just before the close for only 22. The second day was lost and on the third Somerset extended their lead to 273 before the home side embarked on what was, in the context of their first innings disaster, a huge target. That they made it it with four wickets in hand was a stunning achievement and the London Daily News described Townsend’s contribution thus, the tall left hander, taking every risk, hit with astonishing power and made 84 out of 119 put on for the first wicket in 75 minutes.

Townsend married in 1909 and had three sons, two of whom played First Class cricket. The eldest, Peter, played twice for Oxford University in 1929, and the middle brother David also played for Oxford. David’s career was rather more impressive however, winning a blue in 1933 and 1934 and then in 1934/35 in the Caribbean he gained three Test caps against West Indies. He was not a great success, but will surely be the last man ever to appear for England in a Test match without ever playing county cricket.

Leave a comment