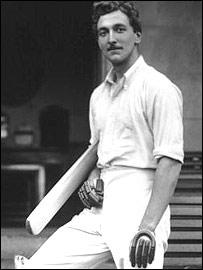

CB Fry – One of a Kind

Dave Wilson |

In cricket, triumph and disaster will come again; in this world, CB Fry will not – RC Robertson-Glasgow

I was an athletics fan in my younger days, and I still recall vividly a trivia section in the 1982 Guinness Book of Athetics Facts and Feats which included pen-portraits on many athletes, however I found three remarkable people particularly enthralling. The first athlete who piqued my interest was Delano Merriweather, an American champion sprinter and extremely colourful character who, in his late 20s and unaffiliated with any college, took to running in swimming trunks and braces. The second was Stella Walsh, born Stanislawa Walesiewicz in Poland, but who moved to the United States aged six and won Olympic gold in the Women’s 100m in 1932 running for Poland; Walsh was shot dead in Cleveland, Ohio in 1980 during a hold-up, the autopsy revealing she had male sex organs – though to be honest, had I seen pictures of Walsh before reading that piece I may have been less shocked (search on the web and you’ll see what I mean).

The third was a list of the achievements of one Charles Burgess “CB” Fry, whom it referred to as the “epitome of the great all-rounder”; the entry on Fry claimed that he had broken the world long jump record while at university, represented England at all three major sports, football, cricket and rugby, served on the League of Nations, ran a naval training ship, published his own magazine and was offered the throne of Albania! I spent quite some time trying to learn more about this most fascinating of men, though I subsequently found out that some of the above eulogies were somewhat enhanced (possibly the editor was quoting from Fry’s own autobiography, Life Worth Living – Fry was never one to let the truth get in the way of a good yarn). By way of example, I often saw it written that Fry held the world long jump record for over 20 years – the IAAF did not actually start officially ratifying world records until 1912 however the unofficial world best, set by Charles Reber of the USA in 1891 and equalled by Fry two years later, was actually exceeded just eighteen months later by Ireland’s John Mooney; Fry actually held the varsity record for 21 years. Nevertheless Fry did equal an athletics world best and that is worthy of the highest praise, no embellishment necessary. Moreover, it turns out he was not in fact offered the throne of Albania, rather the Albanian authorities were considering several high-profile English gentlemen, preferably with money to deposit, as being worthy of the position, Fry being one of them, though it never got any further than consideration (possibly due to Fry’s financial situation). Fry’s extensive achievements were recognised by the BBC when he was honoured as one of the very first subjects of Eamonn Andrews’ This Is Your Life in 1955 – guests included former Test cricketers Sir Jack Hobbs, Sydney Barnes and wicket-keeper “Tiger” Smith.

However, when I finally started to look at Fry’s achievements at cricket it came as somewhat of a surprise that, while in first-class cricket he had few peers during cricket’s Golden Age, in Test cricket he seemed to have been much less of a luminary. In this feature we’ll try to get to the bottom of just why it was that Fry was found wanting at cricket’s highest level, but first and in order to better understand why his Test career must, when compared to his domestic exploits, be considered a relative failure, we’ll take a detailed look at his cricketing career – because of his many noteworthy performances this will necessarily require a discussion of some length, so this feature will be presented in two parts. In the second part we’ll analyse Fry’s batting in detail.

Fry excelled in all sports as a youth but his cricket prowess first became apparent at Repton School and later at Oxford University; it should be noted here that while at Oxford he first exhibited signs of the mental illness which would blight his life to a significant degree in later years, the result on this occasion being less-than-inspiring exam results. By 1891 he had caught the eye of Surrey although they released him before he played any first-class matches for them, and in 1894 he first played for Sussex, which county also boasted the services of the great KS Ranjitsinjhi. The MCC toured South Africa in the winter of 1895-96 and Fry was selected as part of the touring party, mainly because Ranji put his name forward in the knowledge that as an Indian he himself would not be welcomed there. Fry’s early form on the tour led Cricket magazine to describe him as “not apparently being possessed of a great variety of strokes”. Nonetheless, he proved while in South Africa that he had the technique to cope with wickets and attacks which were beyond his colleagues – Lord Hawke was to opine that “the experience he gained on matting wickets made CB Fry the great bat he subsequently proved to be”.

Though for this piece we’re not really interested so much in Fry’s bowling it should be noted that he was branded as a “chucker” as early as 1892 while at Oxford, and was even mentioned by name over that incident in the 1895 edition of Wisden and, perhaps more tellingly, called out by his friend and team-mate Ranji in 1898 (“…the action of…Fry constitutes in every sense a throw”) and also Gilbert Jessop. Umpire Jim Phillips was the first to make a point of no-balling chuckers and as such his relationship with Fry was somewhat strained. The controversy over Fry’s action (his fast-medium style was described as “bent-arm”) continued throughout the 1890s and was once again highlighted in Wisden in 1899. The matter came to a head the following year when the county captains got together and drew up a list of ten bowlers they agreed not to bowl the following year because of their suspect actions – Fry’s name was prominent among those listed. There was some suggestion that several of the umpiring decisions were pre-meditated in order to rid the sport of throwing and Fry therefore felt that he was being treated unfairly, given that he went for long periods without being called at all and that his action had, if anything, improved over time. In any case at that time bowling was more the forte of the professional so Fry was presumably content to further his batting career without distraction. Even so his performances with the ball were not insignificant, as 160-plus wickets at a shade under 30 will attest.

Though an amateur Fry was not at all of independent means and, forced to take a position teaching at Charterhouse he was not able to play much competitive cricket in the summer of 1896, thus removing himself from contention for selection to play the visiting Australians that year. The next two years were also indifferent as regards cricketing performance, but in 1898 he discovered that his faculty for fine prose opened the door to a more lucrative journalistic career which would allow him to earn much more than teaching and in a shorter time to boot, thus freeing him up to play more cricket. Fry’s talent for journalism was also manifest in his publication of Fry’s Magazine, which featured outdoor pursuits and which he published for several years before the war. The involvement with writing, coupled with off-season coaching from Alfred Shaw saw him play well enough in 1899 to impress WG Grace, who selected him for the first Test against Australia that summer (Shaw was a fascinating character himself – he bowled the first ball in Test cricket as well as taking the first Test five-fer and, at 52 was considered good enough to return to county cricket, bowling more than 500 balls against his old team Sussex; try and find a picture of him – he had at one time the most impressive sideburns). Fry opened the batting with Grace and as they walked out to the wicket Grace offered these instructions – “Look here, Charlie Fry, remember I’m not a sprinter like you” – prophetic words, as Grace’s poor running between the wickets held Fry to a 50 in his first Ashes innings that could easily have been substantially more; despite this promising start, in the second innings Fry was not able to carry forward his good form, taking an hour to score a nervy 9.

By the time of the second Test, Fry had himself unwittingly ended the Grand Old Man’s Test career – co-opted by Grace onto the selection committee (showing the high esteem in which he was held even at that early stage of his career), he was asked by WG if he thought Archie MacLaren deserved to play, and in answering in the affirmative sealed the great man’s fate as he then stepped down in favour of MacLaren (though Grace was by then over 50). Fry performed poorly with 13 and 4, so for the third Test he was demoted to number six, managing 38 in a draw. His domestic form going into the fourth Test was impressive, with two successive centuries, one for the Gentlemen against the Players, but even more impressive than those performances was the 97 out of 116 he made in an hour against the might of Yorkshire. Once again however he failed in the Test with scores of 9 and 4, but again some impressive performances for Sussex, including 181 against the Australians, saw him selected for the final Test where he at last showed demonstrated his gifts at the international level – going in at number four, and having been told to hit out he responded with an unbeaten 60 at a run-a-minute by the time stumps were drawn, though significantly he was out first ball when play resumed the next morning.

The following year saw an interesting incident early on when, being well set against Essex, he was so dismayed to be given out LBW that he petulantly flipped off the bails – an early indication of his surprisingly sensitive nature, though his response was to go out and score 101 out of 138 in the second innings. A run of poor form was then offset in the grandest fashion when he became the first to ever score a century and a double-century in the same match – his 229 in the second innings against Surrey included a partnership of 197 with Ranji which rocketed along at the rate of two-a-minute. Later that season his prowess in difficult conditions was once more in evidence as he and Ranji scored 213 of 400 on a rain-affected wicket. His great form meant that in the next match he was aiming for a record fourth successive hundred but, being hit on the elbow when on 96 he was out without further troubling the scorer. Ironically he hit another century in his next innings which could so easily have been his fifth in a row, this time he and Ranji accounting for 214 of 299. Fry ended the year with 2,325 runs at 61.18, easily his best season so far but still some way behind Ranji’s average of 87.57.

After poor form to start 1901, Fry’s composure in trying conditions was evident once more as he carried his bat for 170 out of 254 against Notts, no one else in the side managing even 25. Three double centuries in June gave him 1,110 runs for the month, and in August he scored more than half his side’s runs in both innings (88 and 106) of a match against Hampshire, that century marking the beginning of a historic run. He followed with 209 against champions Yorkshire (his fourth double of the season), then 149 against Middlesex and finally Surrey, who had cut Fry loose, felt his wrath as he blasted 105 to make him the first man to score four successive first-class centuries. His next innings saw him pass 3,000 for the season with 140 and finally, in September, he played in a fund-raising (though still first-class) match for Rest of England against Yorkshire. His century gave him a record six in a row, a record since equalled by Don Bradman and Mike Procter, but never beaten.

Fry’s soccer career was still in full flower at this point in his career and he appeared for Southampton in that winter’s FA Cup Final, his busy winter possibly contributing to his poor start to the following cricket season. 1902 was very wet, so much so that the average runs per team per game in the county championship dropped by more than 25%, but despite his early season troubles Fry was still selected for the first Ashes Test, though it may be significant that the selection committee included Fry himself. Regardless, there is little doubt that the team chosen was on paper one of the strongest England teams ever assembled, comprising Archie MacLaren, Fry, Ranji, Stanley Jackson, Johnny Tyldesley, Dick Lilley, George Hirst, Gilbert Jessop, Len Braund, Bill Lockwood and Wilfred Rhodes – what a line-up! However, in the Test Fry was dismissed for nought in a game which England would likely have won if not for the weather. He was also dismissed for a duck in the second Test before that too was washed out, leading Fry to call for pitch covering in print, one of several visionary pronouncements he was to make over the years (including a form of central contract for Test players). Following his failures in the two Tests popular satirical magazine Punch was to proclaim “What did Mr CB Fry? Two duck’s eggs!”. He was duly dropped for the third Test but was granted a reprieve when Ranji was injured prior to the match. Once more however Fry failed, stumped on 1 in light so bad that the next man in, Braund, immediately and successfully appealed against it without facing a ball. Managing just 4 in the second innings Fry’s Test record for that series so far read 0, 0, 1, 4 – unsurprisingly he was not selected for the final Tests, which turned out to be the two best matches of the series, both of which are counted amongst the most famous of all time, but they are other men’s stories. Back at Sussex, after a couple of good performances Fry and Ranji determined that they would halt their seasons with the county at that point – Ranji as captain felt that the players were not trying hard enough and Fry, as vice-captain, decided to support him (amateurs did not have contracts and were thus under no obligation to their counties). At this point in his career it was looking as if Fry, like Graeme Hick nearly a hundred years later, had the game to dominate county bowlers but was found wanting against higher class Test attacks. That said, the annual report for Sussex that year mentioned that Fry had been ill during the year, although it did not elaborate.

1903 saw Fry dispense with his customary slow start, hitting 174 (more than half of the Sussex total) in the opening fixture against Worcestershire, and a marathon seven-hour 234 against Yorkshire (his longest innings ever) ensured he was first to reach 1,000 runs. That was a mere prelude to a phenomenal month’s batting in July when he hit two more doubles and another single century, though his 232* for the Gentlemen against the Players was punctuated by an incident with George Gunn as Fry bumped into the Nottinghamshire professional when running between the wickets; while Fry checked on Gunn’s well-being a fielder employed rather sharp practise in attempting to run him out, though fortunately for Fry he missed, allowing Fry and MacLaren to go on and add 300 in under three hours despite this “ungentlemanly” conduct. A score of 160 against Hampshire meant that he had already passed his previous season’s total with two months still to play, and he went on to score twin centuries against Leicestershire, becoming only the third player (after Grace and RE Foster) to achieve the feat on three separate occasions. Fry finished the season with 2683 runs at 81.30 (the next best average being Ranji on 56), his aggregate being a full 500 runs ahead of Surrey’s Tom Hayward, causing one report to suggest that Fry should be handicapped in the future. The Sussex fans showed their gratitude by clubbing together and buying him a car (though, sadly for Fry, not the one he had hinted at).

Fry declined an offer to tour Australia that winter and, with Ranji now in India staking his claim to the throne of Nawanagar, he accepted the captaincy of Sussex for the 1904 season. At the end of May, Fry showed yet again his propensity for outstripping his team-mates in a match against Leicestershire – the home side were all out for 72, then when Sussex batted Vine managed 32 and Ranji 27, however no other Sussex player could manage double figures except for Fry, who amassed an astonishing 191* in better than even time, scoring more than the other 21 players put together! In June he didn?t let up one iota as he hit seven centuries in only 15 innings. Significantly his 229 in August against Yorkshire was derided in the Yorkshire Post for apparently furthering his average as he refused to hit anything on the off, rather churlishly highlighting an apparent weakness in his game which was a sign of things to come. Fry hit four double hundreds that year and approached 3,000 runs, which milestone he may have surpassed but for a bereavement which caused him to miss two games.

The Australians returned in 1905 though Fry’s inclusion in the England side, following his poor performances on their last visit, was by no means a certainty. His form for Sussex was once again superb, including an unprecedented fourth match with a century in both innings, immediately following that with a near-miss, 97 and 201 in his next match against Notts. Scores of 25 and 26 for the Gentlemen of England against the tourists did nothing to placate his detractors as regards his Test place, but although despite this he was indeed selected for the first Test he was forced to drop out following injury. After overtaking Ranji (who was again in India for the year) as Sussex’s highest ever run scorer, Fry hit a sparkling double century against Notts which saw him become only the third player after Grace and Ranji to reach thirteen first-class double hundreds. Though he made only 27 for MCC against Australia he was still selected for the second Test and his innings caused quite a stir, though this time as a result of the Australian tactics.

Presumably aware of the apparent flaw in Fry’s technique, which had been so pointedly highlighted in the Yorkshire press, Darling had Armstrong bowl to a packed leg side so that Fry’s usual scoring strokes were unsuccessful. In fact the Wisden report gives the impression that leg-theory was used against all of England’s batsmen, not just Fry, though this report in Cricket suggests otherwise, and also draws attention to Fry’s shortcomings at the highest level – “The want of success of CB Fry in Test matches has been the subject of so much comment that his arrival at the wicket was waited with anxiety by the vast crowd. He very soon showed that he was comfortable enough and quite at home with the bowling, but he could not get the ball away for the field was so admirably placed for him that the strokes by which he usually scored were intercepted”. The difficult conditions caused by earlier rain meant that Fry was forced to play defensively, taking more than 200 minutes for his 73, though that proved to be the top score of the innings. However, considering Wisden’s view that in the conditions England’s total of 282 was worth 400 on a good wicket, Fry’s 73 may well have been worthy of a century. Even when finally dismissed in bad light Fry was unhappy, claiming that the ball had hit his boot – interestingly the umpire was Jim Phillips, who as mentioned earlier had in the past been a thorn in the side of alleged chuckers such as Fry. The game petered out to a draw with Fry not out on 36 in the second innings. The same leg-theory tactics were then used by Kent with Fry again appearing to show some vulnerability as he was out for 9, but by the second innings when he scored 175 out of 255 against similar field placements such fears were laid to rest, his first innings woes being apparently the result of an arm injury. His century against Yorkshire was promising, considering the third Test was to be played at Headingley, but alas in the Test he could not build on two starts, being dismissed for 32 and 30 and then in the fourth Test contributed only 17 to England’s total of 446 as they won by an innings. Calls for his removal from the Test side were answered by Fry when Sussex met the Australians as he scored 70 out of 103 in even time, once again facing a leg-theory field, and so he took his place for the final Test at The Oval, for what proved to be his coming-out party. Coming in at 32-2 and surviving a near-miss before scoring, he went on to cut many balls to the off to render the leg-theory field toothless and reach his maiden Test century, his 144 coming in 213 minutes with 23 boundaries – Cricket wrote “No better innings has been played in a Test match”, while Wisden enthused “Fry’s innings dwarfed everything else….For the first time in a Test match, the famous batsman did himself full justice….a finer innings he has seldom played”. In his fourteenth Test match and 21st innings, Fry had at last fulfilled his enormous potential at the highest level of the game. Buoyed by this success Fry continued in the same vein for the remainder of the season and duly led the first-class aggregates with 2801 runs at 70. That year also saw Fry join forces with photographer George Beldam to produce Great Batsmen – Their Methods at a Glance, one of the most famous cricket books ever, providing the technical analysis to accompany what became some of the game’s most instantly recognisable images.

A ruptured achilles tendon caused Fry to miss all but two matches during 1906, and the following year saw the return of South Africa. Initially that season Fry had to play with an iron stanchion supporting his injured leg which understandably affected his performance, but he was nonetheless (and to the consternation of the press) selected for the first Test and contributed 33 to a total of 428, though the match was then washed out. After missing more domestic games due to his leg injury his form improved thereafter and he just missed out on twin centuries by one run for the third time, with 125 and 99* against Worcestershire. Though Fry’s form leading up to the second Test was excellent this seemed to be rendered irrelevant by the extreme difficulty of the wicket, England being skittled out for 76 in their first innings. Blythe proved particularly troubling to the visitors and finished with figures of 15-99 but in between Fry played a brilliant innings of 54 in only 65 minutes, again showing that he could overcome a difficult wicket to an extent which eluded his contemporaries – the Daily Mirror proclaimed that victory was due to two men and two men only, Fry and Blythe, the two Charlies. Very much at the top of his game now, he struck a magnificent 187 in his next match against Derbyshire, but was forced to miss more playing time leading up to the third Test. Nonetheless, in the Test itself he again displayed his excellence on a trying surface and against an attack well suited to it with a magnificent 129 as wickets fell all around him – Wisden commented “As an example of self-control under rather trying conditions his innings has perhaps never been surpassed in Test Matches”. Once again however, his great play was not to result in victory, as the game ended in a tame draw. Fry topped the series averages by a full 13 runs over Dave Nourse, though his relatively low average of 44 illustrated the difficulty of the conditions that summer. Despite some periods of poor form he had topped the national averages once again, though surprisingly, given the absence of players of the calibre of Jackson, Foster, Hirst and Tyldesley, Fry was not invited to tour Australia that winter which, considering England lost 4-1, was possibly a mistake, though there had been rumblings in Hove concerning Fry’s availability (or lack thereof) which some saw as detrimental to a settled dressing-room.

Considering his fine play at both domestic and international level the previous year 1908 was a disappointment, as Fry played only 13 first-class matches. However it was not injury which led to his absence this time, rather it was increased involvement with the training ship Mercury, run by his wife Beatrice and one Charles Hoare. Just to digress a little here, the three of them formed a kind of bizarre love triangle – Hoare, a married father in his thirties had begun to pursue Beatrice when she was just 15, and had eventually fathered two illegitimate children by her, which caused quite a scandal at the time and on a national scale to boot; when Fry married Beatrice she was already 36 and some ten years his senior, while Hoare acted as a benefactor to Fry for some time as well as helping with the finances of the Mercury. Hoare’s death in 1908 led to Fry’s increased absence from cricketing circles, as he was involved first in settling Hoare’s affairs and then in additional duties related to the running of the training ship. This situation also led to rumours, owing to the fact that the ship was docked at Hamble in Hampshire, that Fry was about to “jump ship” to that county, which rumours he made no effort to dispel. As a result of this upheaval Fry’s season was perhaps unsurprisingly somewhat inconsistent, the highs including a sparkling 214 against Worcestershire and a century for the Gentlemen against the Players. The lows meanwhile started with a match against, ironically, Hampshire when Fry took the Sussex players to Ranji’s mansion overnight and, on seeing rain the next day assumed there would be no play or at least a delay. As a result, nine of the team arrived late for the following day’s play and Fry, with the crowd showing its displeasure at being kept waiting, could manage only 4. Fry then missed the rest of the season, leading Cricket to point out that he had managed to avoid travelling to Gloucestershire since 1904 (when he had been upset by a fan) and Notts since 1905 when he had exchanged words with one of the game’s great characters, Tom Wass – this avoidance of those two counties again hinted at his deeply sensitive nature. Fry’s popularity, such as it was, had definitely taken something of a knock during 1908.

Fry turned 37 in 1909 and celebrated by finally making the oft-rumoured move to Hampshire, citing his increased involvement with the Mercury, and quickly enhanced his popularity, at least locally, when he arranged and participated in a match to commemorate a famous Hambledon vs All-England match which had taken place 131 years earlier. Fry did not start well in the county matches, however he soon found his feet and, after a series of scores over 50, he made his maiden century for Hampshire on a wicket that no one else could master. Nonetheless Fry could find time to appear in only nine games that year, though that was at least partly explained by his involvement in that summer’s Ashes series. His series began in inauspicious fashion when he badly dropped Macartney, and then suffered the ignominy of a golden duck at the hands of the same player – the Daily Mirror described his first innings play as “jumpy and ungainly”; Fry, though thoroughly outplayed by Hobbs in the second innings nonetheless had the satisfaction of hitting the winning runs. Legal problems involving his brother-in-law, who was involved in a fraud case, necessitated Fry withdrawing from the second Test, and his return for the third Test was not a success as he could manage no better than 1 and 7, with the result that he was dropped for the next Test. Good form for Hampshire saw him reinstated for the final Test and he once again displayed his liking for The Oval with a fine 62 in the first innings, when he was run out by Rhodes, and an undefeated 35 as the match ended in a draw.

1910 was not a satisfying year from a cricketing point of view for Fry. He missed much of the season because of domestic matters – the now 48 year-old Beatrice gave birth, which was apparently a response to Fry’s alleged affair the previous year, explaining much of his absence from cricket in 1909. In the event he appeared only twice for Hampshire, though he managed a century in the second match, against Worcestershire.

A slow start in 1911 was perhaps not surprising considering his lack of appearances the previous year, but Fry soon began to score at an astonishing rate, including 150 against Derbyshire and 104 against Kent. His 121 against Worcestershire turned the match, and his twin tons against Kent were significant as it was the fifth time he had achieved that feat. A third consecutive century followed against Gloucestershire or Glos, Fry finishing on 258*, the highest of his career and taking him to an unprecedented 15 double hundreds. In 26 innings that year he hit seven tons and eight 50s to average 72, his best since 1903, and all this when only a year short of his 40th birthday. Taking time off (and hitting three consecutive centuries at Hamble in the meantime) he returned without missing a beat, hitting 102 for Rest of England against Worcestershire to end the season with four tons in a row. Fry’s great play led to him being asked to lead the MCC tour to Australia that winter, however he delayed in responding despite solid performances as captain for the Gentlemen against the Players and, after abortive fundraising to help finance the trip he declined the MCC’s offer. Fry was fated never to tour Australia.

After easing himself back into things the previous year, 1912 proved to be one of Fry’s busiest yet. First, he wrote a book called Cricket (Batsmanship) which, while not at first lauded has since come to be recognised as a classic (ironically, considering the criticisms levelled at Fry over his technique, by far the longest section concerns driving). Fry quickly put the theory into practise with a series of high scores, though Cricket‘s description of his century while captaining the Gentlemen against the Players suggests his technique was still very much in favour of leg-side play; nonetheless, by averaging over 100 in the County Championship he still led Hampshire’s (and the national) averages by a significant amount, though he batted only seven times. His form was good enough to lead to an offer of captaincy for the forthcoming winter tour of Australia by MCC, however he delayed in responding and, despite good performances as captain of Gentlemen vs Players and an abortive fundraising project to support the trip, he eventually declined the offer. Fry would never go on to tour Australia.

An enthusiastic proponent of the forthcoming Triangular Tournament, he was at last appointed captain of England, though he did not appreciate the fact that it was for the first Test of the tournament only. Fry refused and insisted instead that he be made captain for all six Tests, and such was his standing that his demands were accepted over the claims of successful Ashes captains Johnny Douglas and “Plum” Warner. He even got himself elected to the selection committee, along with two other members of his own recommendation, John Shuter and HK Foster, which situation generated a significant amount of criticism. Australia meanwhile was seriously under-strength following a dispute between players and management, leading to the omission of such luminaries as Trumper, Hill, Armstrong and Cotter. During the build-up, Fry opened the batting with Aubrey Faulkner for the MCC against Notts, the two of them putting on 191 for the first wicket. In their first match of the tournament against South Africa, England was in a commanding position after bowling out their opponents for only 58. Already with a substantial lead when Fry came in to bat, he was nonetheless unable to settle and was bowled for 29. His performance was further punctuated by poor fielding and questionable captaincy as regards use of his bowlers, though England still won easily. The next match against Australia was virtually completely washed out, Fry taking a record three days to score 42, though his eventual run out was dubious. He was criticised for not bowling Woolley and for bowling Rhodes hardly at all, though interestingly Douglas Jardine agreed with his tactics of keeping his weapons under wraps some twenty years later. At Headingley Fry scored only 10 and 7 against South Africa (“playing a game quite foreign to himself”), but again England won handily – however the Daily Express took the opportunity to point out how personally Fry seemed to take each dismissal.

Moving on to Manchester did nothing to improve either the weather or Fry’s form, his innings of 19 being played with a perceived lack of confidence as the game was washed out. In the next match, at The Oval, South Africa were dismissed for 95 in their first innings when Fry at last let Woolley loose with the ball, however Fry’s batting let him down once more as he was dismissed for just 9. Fry’s penchant for mastering difficult wickets seemed to have deserted him, at least for the time being, but the South Africans also had no answer as England once again won easily, thanks mainly to Barnes’ 13-57. The final game against Australia was then determined to be the tournament decider (amazingly no consideration had previously been given to what would constitute the winner of the tournament until this final match!), and having won the toss Fry elected to bat. Batting at number four he walked out to, in Fry’s words “unanimous booing from our 30,000 supporters” – actually the crowd was around 16,000 and apparently the booing was not quite unanimous, as AA Thomson was to reveal years later – the crowd’s discontent was partly because Fry had delayed the start of the match hoping to maximise England’s advantage on a wet wicket, but also partly as a show of support to the deposed captain Douglas, at last recalled for this final match (though only as a late replacement). Fry was once again a failure with the bat, making only 5 and taking 45 minutes to do so, much to the crowd’s displeasure but England managed 245 and then bowled out Australia for 111, Fry’s decision to hold Woolley back in previous matches vindicated here as the great all-rounder took 5-29. England then slumped to 7-2 and Fry came in under the greatest possible pressure – Whitty on a hat-trick, a difficult pitch, poor light and once again booed all the way to the crease. Surviving until stumps, he resumed next day after another overnight downpour but was lucky to survive treading on his wicket after convincing the umpire he had completed his shot prior to the incident. Fry at last found his form and made 79 out of 175 on a “beast” of a wicket, described by Wisden as “a masterpiece of skilful defence”, and in the process he rediscovered his mastery of tricky conditions – Tiger Smith opined that it was impossible for anyone but Fry to score on such a pitch. Wisden also commented that “For once in the Test matches he was his true self”. As an interesting aside, when Australia batted again a catch Fry made when he yelled “George” (at George Hirst, not even in the side but playing for Yorkshire at Huddersfield) was either a sign of his confused mindset or a slip of the tongue. In any event Australia were all out for 65 and England were tournament champions, vindicating Fry’s questionable decision-making and, with his insistence on holding back Woolley, showing his willingness to make unpopular decisions for “the greater good”, again showing parallels with Douglas Jardine some years later. The response of the crowd was very positive after the game but Fry’s feelings had been hurt (“The time for them to cheer was when I went in to bat to save England and not now we’ve won the match”) and he refused to come to the balcony and acknowledge them. Fry had at last won a match for England, some 16 years after his debut – he remains one of the few undefeated England Test captains.

Fry played no first-class cricket during 1913, however he returned to play for Hampshire the following year and incredibly scored 41 and 112 (his 93rd first-class ton) in his first game back. It is possible that if he had played a full season during 1913 he might have gone on to make 100 hundreds although whether or not he was aware of that it is not clear. However that innings and a 50 were his only innings of note that year, and interestingly in the Gentlemen vs Players match he was quite happy for his bowlers to use leg theory (as the Aussies had previously done against him). His biggest game of the year was while captaining the Rest of England vs the MCC team due to tour South Africa; Fry’s 70 put them on the way to an innings victory.

After the Great War, Fry did not play first-class cricket in 1919 but was persuaded to re-join the ranks the following year at the ripe old age of 48. After playing in Phil Mead’s benefit he appeared in Hampshire’s match against Notts and astonishingly made 137 and 57, in each innings hitting more than twice as many as any of his colleagues! Such form led to an invitation, received on his 49th birthday, to captain England against the touring Australians the following year, though in fairness by now the prospect of facing Gregory and McDonald did not appeal to him. Good form against Kent (96 and 45) preceded Fry being named as captain for MCC against the tourists, however a knee injury led to his withdrawal. Fry agreed to be considered for the second Test, subject to being happy with his own form, however 0 and 5 put paid to that notion, though he subsequently persuaded the selection committee to play his county captain Lionel Tennyson, which recommendation was repaid with an undefeated 74 from Tennyson in the second innings (though England were again heavily beaten). That defeat had Fry’s name in the frame once again as England captain and as Hampshire were due to play the Australians he had a chance to show his form with the bat. This he did, with a 50 and 37 followed by 61 against Notts, however a finger injury picked up against the Australians meant he was not in the end available for the third Test.

And so Fry’s cricketing career came to an end – despite not joining Hampshire until age 36 and playing for them until he was almost 50, he still has the best career average in the county’s history. Fry’s health deteriorated following his retirement from cricket and mental illness kept him out of the public eye for almost six years in the late 20s and early 30s – as the first known episode of his mental health issues occurred during his final year at Wadham College it is quite possible that there were others in between which did not come to light. As testament to the seriousness of his illness Fry was to undergo electro-shock therapy for at least ten years during and after his illness. How much Fry’s condition was exacerbated by his wife’s mental toughness and generally callous disposition we can only guess at – her controlling nature can be evidenced by the fact that she had even interfered with his input to the England Test selection committee. As to his unhappy marriage and the impact on his state of mind, it is notable that when Beatrice met her son Stephen’s prospective wife, she described her son as being “no good…he’s just like his father”.

Plum Warner reckoned Fry to be “highly strung…like a rather nervy racehorse”, and William Pollock pointed out that Fry’s appearance and aloof demeanour alienated many among the cricket public. It is also notable that following his election campaign he was suffering badly from nervous exhaustion. In his later years one of the Mercury trainees recollected that Fry would lie awake recalling cricket matches and his role in them from some 50 years before – perhaps he suffered from the melancholy which afflicts many cricketers on retiring from the game, though one would think a man like Fry would be able to find plenty to occupy himself! One of the saddest aspects of Fry’s mental issues was his distancing of himself from his great friend Ranji, as he developed an unreasonable distrust of Indians which, by the time he was more aware he was unable to rectify as by then sadly Ranji had passed on.

There has surely never been a more complex character in the world of cricket than Charles Fry – interestingly he always felt that he had not lived up to his full potential although in this writer’s opinion this may only have been true in the Test cricket arena – but as Fry himself wrote in “Cricketers I have Met”: “Cricket finds the truth even more surely than wine” .

Brilliant. Really enjoyed that.

Why has he never been profiled before now?

Comment by Hurricane | 12:00am BST 30 March 2012

[QUOTE=Hurricane;2820196]Brilliant. Really enjoyed that.

Why has he never been profiled before now?[/QUOTE]

Probably I’m the only one sad enough to be that interested in him. Seriously, this is partly my point – his relative shortcomings at the Test level mean he’s nowhere near as well known as his contemporaries such as Trumper or Ranji.

Interestingly Martin (fredfertang) has a copy of a biog on the indomitable Mrs Fry which might be interesting reading. I also just got hold of a copy of his book on Batsmanship – it’s a great read, full of asides like “Imagine you were walking down a country lane and bumped into RH Spooner, and you put upon the good nature of this good-natured man and had him use his walking cane to demonstrate his stroke.” Or “80% of cases of loss of form can be put down to either lack of practise or disorders of the liver”; certainly the latter might be true in the case of a Doug Walters or a Rodney Marsh!

Comment by chasingthedon | 12:00am BST 30 March 2012

Found this – he was 48 by this time.

[url=http://www.britishpathe.com/video/englands-cricket-captain-aka-mr-cb-fry-1/query/cricket]ENGLAND’S CRICKET CAPTAIN? aka MR CB FRY – British Path[/url]

Comment by chasingthedon | 12:00am BST 30 March 2012

Another great piece Dave. I’ve always been fascinated by Fry – simply the most unfairly gifted all-round human being in the history of cricket IMO. He’d be a strong contender as a guest if I were hosting one of those fantasy dinner parties – though if Cardus is to be believed (and why wouldn’t he be?), it might be difficult for anyone else to get a word in!

Comment by The Sean | 12:00am BST 31 March 2012

Enjoyed reading that, CB Fry was one hell of an athlete.

Comment by chris.hinton | 12:00am BST 31 March 2012

On top of it all, a devilishly handsome bugger.

Interesting question, really: would you swap places for the man who has [I]all that[/I] but also mental illness. Possibly not.

I think the real decline began when he left Sussex and joined Hampshire. What a dreadful step down that must have been.

I love the fact that his illegal bowling action led him to be occasionally referred to as “CB Shy”.

Comment by zaremba | 12:00am BST 31 March 2012

Amazing read, gives us a good insight into the likes of WG Grace too which I found astonishing.

Comment by slowfinger | 12:00am BST 1 April 2012

Really enjoyed reading this,Dave. I’m going to hunt down my Iain Wilton biography of the great man as a result.

Comment by Gareth Bland | 12:00am BST 3 April 2012

Just finished reading ( life worth living) about c b fry,absolutely astonishing read why has a film not been made about this genius of a man? No knighthood either,very strange book should be compulsory reading for anyone who likes cricket,what a life he had.

Comment by John pope | 8:48pm BST 13 July 2019

I’m doing a piece on Fry following Andy Murray being currently promoted as Britain’s greatest sportsman. It seems to me that the accolade should actually go to Fry. A very controversial character but one whose all round sporting prowess seemed to have no bounds. Although his record of six consecutive first class centuries was later equalled by Bradman and then Procter it has never been bettered. Stripping away some embellishments it is still an astonishing story. My one question is: did he ever get any awards for his sporting efforts? Of course those were the days when sportsman were not awarded gongs unlike today when they are seemingly dished out two a penny.

Comment by Julian Denny | 11:01am BST 30 July 2024