Boycott’s Outlier Summer

Johnny Blades |

Card #54 of the 84-card pack is a photo of his straight drive. The elbow of his bent left arm is high, bringing the forearm in line with the bat as his head, latched on to the line of the ball, leads his body to move through the shot with perfect balance. On the back of the card is a distant woolly picture of cars parked among the grass and trees of Yarra Park next to the Melbourne Cricket Ground back in 1980, part of a wider aerial shot which forms in total when the complete pack of these cards is lined up in order and placed face down.

This series of player cards by Scanlens featured the five teams involved across a two-year cycle of World Series Cricket in Australia, sponsored by tobacco company Benson & Hedges. It was the first southern summer since the end of the standoff between the Packer Network which had created World Series Cricket, and the sport’s establishment. When the truce was sealed, Packer’s Channel Nine was granted exclusive rights to televise the matches. These were new times in cricket, with day/night games played under floodlights at night, coloured uniforms, big gates and slick tv coverage, generating merchandise such as the cards.

My starting point of interest was New Zealand’s involvement in the 1980/81 World Series Cup alongside Australia and India. The excitement of the new product and the high drama in some of the games, culminating in the underarm controversy in the finals, earned cricket a lot of new Antipodean followers of whom I was one. A year or so later, the Scanlens cards started to turn up in the sweaty hands of kids in Wellington, sold with bubblegum at dairies (general stores). For ages, I had only about twelve of the cards – including a couple of double-ups: India’s Gundappa Viswanath and Gary Troup of New Zealand – until someone along the road traded me several dozen cards which gave me momentum to pick up the rest of the pack before long.

Thanks to that summer, New Zealand’s beige glory days and their yellow chested enemies with big moustaches are well etched into my memory. Cricket felt exciting at that time. Not just because I was a kid starting to play the game myself, but because the format of One Day Internationals, cricket in bright colours, had revolutionised the sport. The next big revolution of course was about three decades later with the rise of T20 cricket.

If there were any remaining doubts that the rise of T20 cricket has dramatically changed the approach of batsmen in other formats, the 2023 edition of the ODI World Cup should have put paid to that. There’s never been a time when batsmen have had it so good, what with fielding restrictions, flat pitches, smaller boundaries, chunkier bats and improved protective equipment. This is good if you are attracted to the game by big hits and large totals. But it’s sometimes forgotten in the frenzy of sixes how a compelling ODI cricket game can also involve test match-like passages where the real chess action happens: mind games and crunch points; swings and roundabouts; patience and attrition; survival against the odds; late twists.

For us across the Tasman Sea, the World Series Cup in Australia in 1980/81 became compulsory television viewing as the competition progressed, and New Zealand’s confidence and success as a team grew. It was something of a coming of age for the sport in New Zealand. Part of the appeal was the success of Richard Hadlee, a champion who needs no introduction, and we soon realised why Australian crowds abused him so much – because deep down they respected him. He was the kind of player who drew crowds. The importancr of drawing crowds was something both the Packer Network and the sport’s establishment including the Australian Cricket Board could agree on, following the end of their bitter standoff. When the truce was sealed, Packer’s Channel Nine was granted exclusive rights to televise the matches. These were new times in cricket.

Post truce

Less known to me was the first iteration of this World Series Cup tri-series format which Australia would go on to host for decades to come. The 1979/80 World Series Cup also involved England and the West Indies who both toured Australia at the same time. Strangely, the respective test series against the touring teams were played concurrently. So Australia’s first test against the West Indies was followed by its first test against England before the second test against the West Indies and so on. Furthermore, the 14 matches of the one-day tri-series were played in and around the six tests. It was an intense season for Australian captain Greg Chappell, which was followed by an even busier season the following year, which may explain his burnt-out state of mind when he instructed his brother to bowl the infamous underarm delivery on February 1st, 1981.

However, in those last weeks of the 70s, Chappell and co went into battle against Clive Lloyd’s World Champion West Indies side and England led by Mike Brearley. The English refused to put the Ashes on the line for the test series. This was just as well because Australia won 3-nil, a far cry from a year earlier when Brearley’s team toured and thrashed an Australia team that was without its main players who were off competing in Packer’s World Series Cricket.

England’s 5-1 victory retaining the Ashes in 1978/79 had been achieved by much the same squad who returned the following year. Again under the wing of assistant manager Ken Barrington, who’d led a cheery squad to Australia the previous southern summer, the English arrived in Sydney in early November and stayed in Australia for over three months.

Among them was Geoff Boycott, one of the all-time great batsmen, a Yorkshireman known both for his huge accumulation of runs and a reputation for selfishness which put him offside with many teammates and administrators over the years, but also helped his team win fairly often. On the cusp of 40, Boycott was on track to become England’s most prolific batsmen in tests, having already become one of the few to score a hundred first class centuries. However despite being up against a weakened Australia side, Boycott had performed poorly down under in 78/79.

Return down under

That earlier tour came at a bleak time for Boycott, especially as his mother had just died of cancer. Even though from a team spirit perspective the tour was one of the most harmonious, Boycott’s life was in turmoil. Without scoring his normal heap of runs, Boycott fell into a slump worsened by off-field issues, chiefly the protracted controversy over the captaincy of his county, Yorkshire. He was withdrawn and frequently found himself the butt of practical jokes by the young all rounder and rising star Ian Botham who once purposely ran out Boycott when batting with him in a test in order to help revive the team’s run rate. They’d given the star batsman a ridiculous nickname, ‘Fiery’, with apologies to another all time great from Yorkshire who had that tag first.

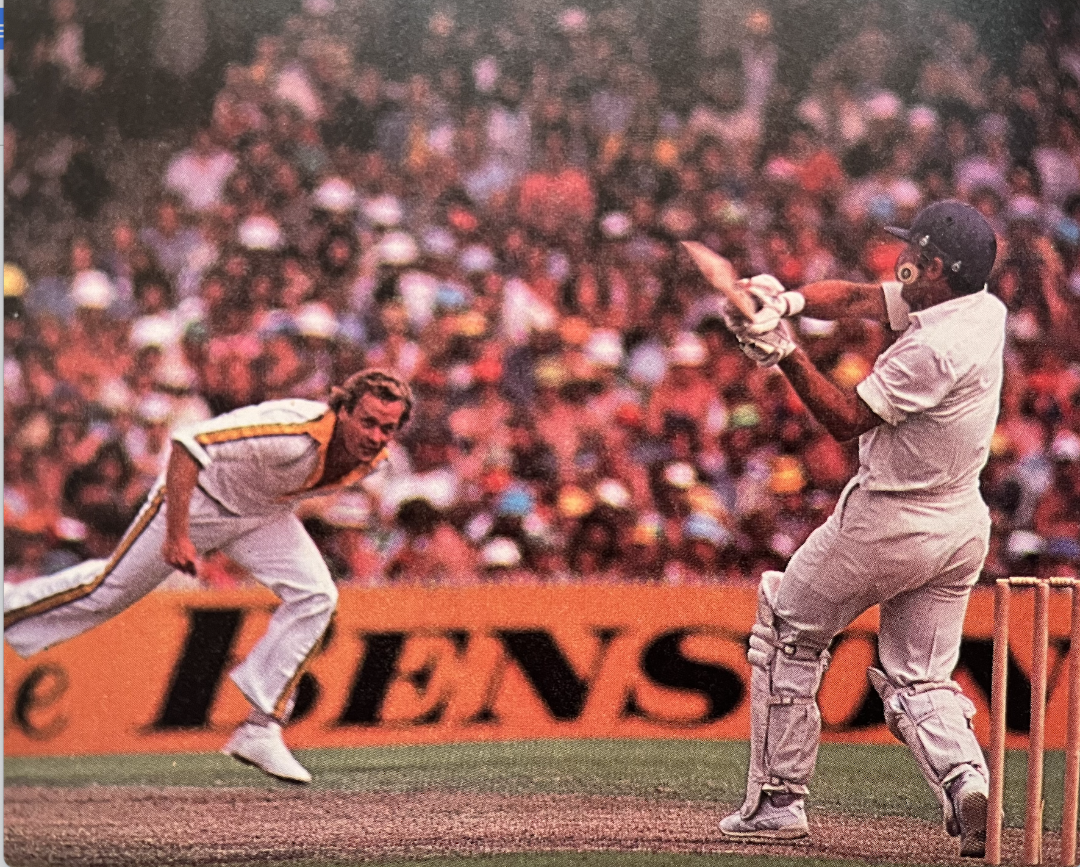

The Boycott who arrived in Australia in late 1979 was far more together and in form. He would need to be because this time England wasn’t facing Australia’s B or C team, but instead the top team. Chappell led a full strength side, with a brutish pace attack led by firebrand spearhead Dennis Lillee and including Jeff Thompson, Len Pascoe and Rodney Hogg, a gang of ultra-macho speedsters just waiting to grind the Poms into the hard Australian dirt to balance the ledger after the 1978/79 Ashes fiasco.

Australian revenge was exacted in the tests. England bowled well but failed to post competitive totals. Chappell and Allan Border led with the bat for Australia while Lillee grabbed plenty of wickets. For England, only Botham scored a century. Boycott however notched one standout test performance in Perth when he was stranded on 99*. It wasn’t the only time that southern summer that he’d carried his bat. He then did it again during the ODI series, which was when England played its best cricket that summer, a dynamic tournament in which not only did Boycott have to face Australia’s pace attack, but also the West Indies’ four-headed battery of Andy Roberts, Michael Holding, Joel Garner and Colin Croft, the most feared bowling attack of modern times.

White balls under lights

England largely refused to wear coloured clothing for the ODIs. Its players stayed in whites, but had the option of dark blue pads and gloves, which Boycott and others opted for on occasion. However England reluctantly agreed to the use of white balls during day night fixtures. Mainly the team was familiar with the 50-over format. Although one-day international cricket was still in its infancy, the limited overs competitions had been played in England’s county scene for a long time. Earlier that year, England lost to the West Indies in the ODI World Cup final at Lords. Boycott played a prominent role in that game, giving his team a chance of victory in a big opening stand with Brearley, but also unfortunately complicating his team’s chances of winning by neglecting to increase the run rate in time.

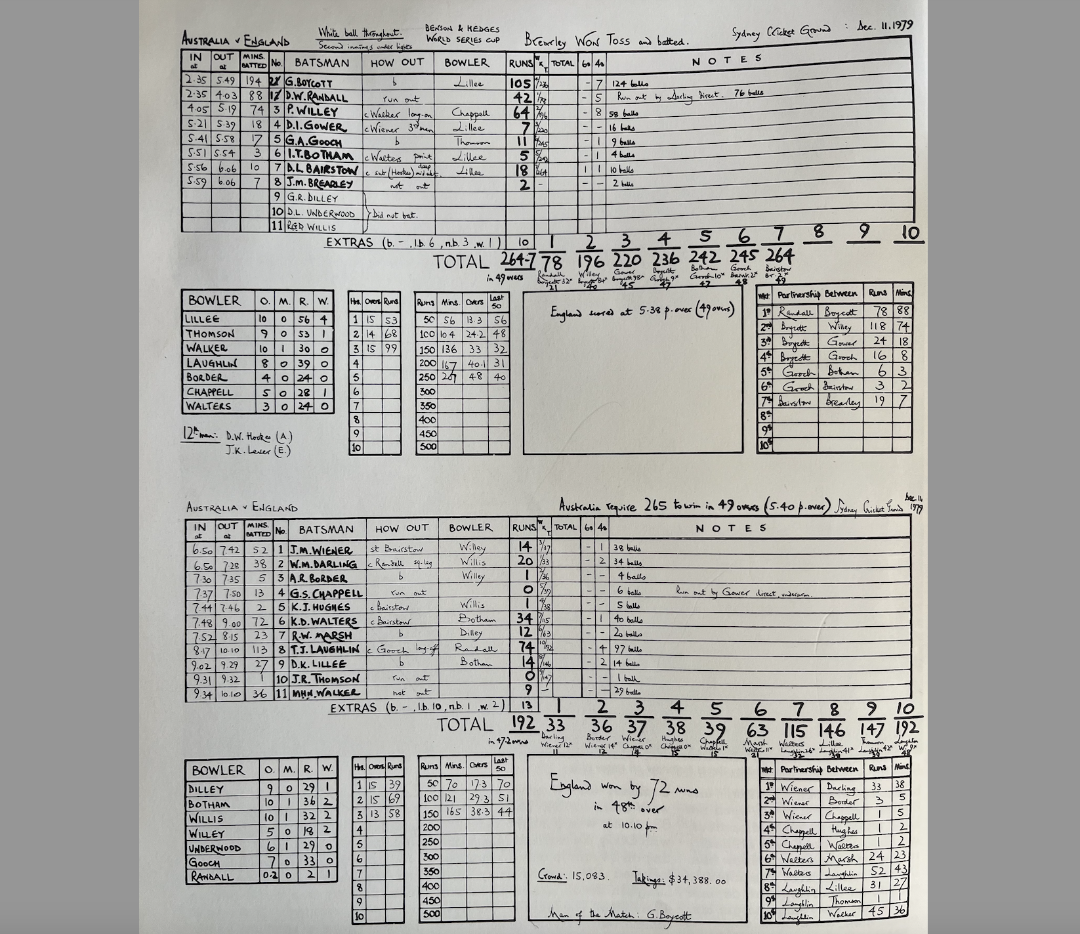

Lessons were learnt by England, including not to bat Boycott and Brearley together at the top of the order. So that’s how they did it in Australia. Boycott opened, while Brearley came in around 6. For Boycott it was a sequence of innings that would confound those critics who said his batting style was too negative for the new format. For me this was brought into focus decades later when I stumbled upon a book summarising the summer’s limited overs cricket by Packers PBL publishing arm. The book – appropriately titled ‘One-Day Cricket’, was on sale at a second hand bookstore on Ghuznee Street, and I didn’t hesitate to purchase it. Compiled mainly by Richie Benaud, the book features match reports and photos which brought alive those images on the Scanlens cards, as well as handwritten scorecards. Those scorecards are evidence of a series which stands as an outlier in Boycott’s international record.

The Yorkshireman wasn’t picked for England’s first outing in the comp, a 2-run win over the West Indies, some sort of consolation after Lords a few months earlier. But when England’s team sheet to play Australia at Melbourne on December 8th was issued, Boycott’s name was at the top of the batting order. Cricket journalists and commentators were doubtful whether he would do well in the fast-paced limited overs games.

Shot maker

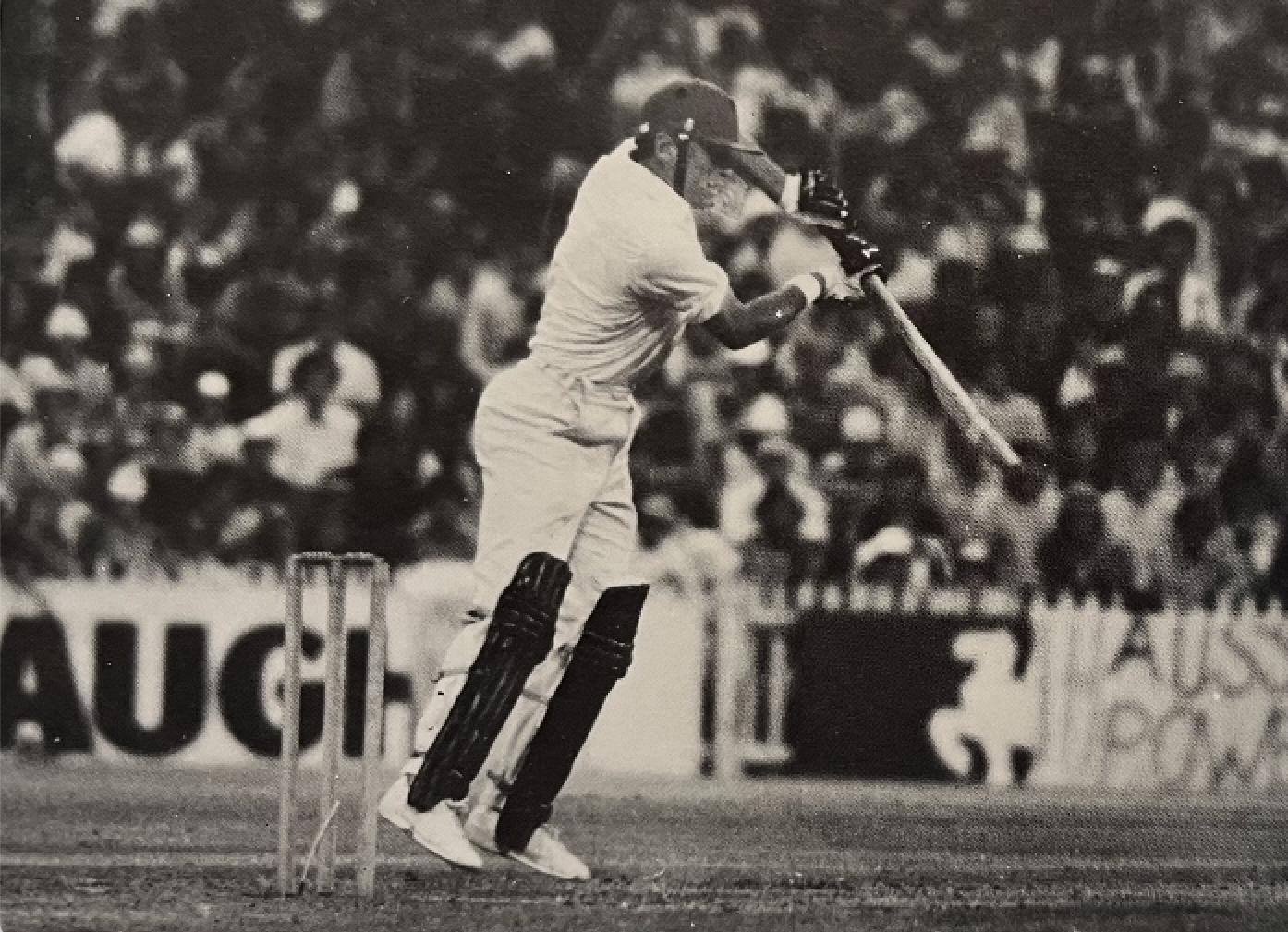

Brearley opted to field first at the MCG, and Australia scored 207 in their fifty overs. Boycott was textbook correct as ever, and from early on showed a hunger for singles. He got England off to a 71-run opening stand with Derek Randall in 21 overs before putting the foot down with Peter Willey in a second wicket stand of 63 in just 47 minutes. Since being torn to shreds by Hogg the season earlier, England batted cautiously against this moody speedster. Lillee was also in outstanding form that Summer and took many English wickets, so the tourists had their work cut out for them. But Boycott was able to comfortably milk runs off all of the Australian bowlers. He looked in control against short balls. From the commentary box, Bill Lawry remarked that “he’s a good player off the back foot when he’s in touch and prepared to play his shots”. Boycott’s 68 off 85 balls included seven boundaries. England won by three wickets in the 49th over.

Three days later, the same two sides squared off in Sydney. Lillee and Thomson tore in with a vengeance, but prioritised speed and venom over accuracy. Boycott stroked the ball through covers off the front foot, rocked on to the backfoot for punches through point, and guided balls off his hips into gaps with ease. An opening stand with Randall was worth 78, before a partnership with Willey produced 118 runs in just 74 minutes. The Australians were worked all around the SCG, as keen running between the wickets applied pressure on the homeside. Boycott notched his first ODI century before being bowled by Lillee for 105, scored in 124 balls including seven boundaries, which was a pretty decent clip for those times. This was still over four decades away from the phenomenon known as BazBall, and strike rates were usually well below where they tend to be nowadays. England went on to a total of 264, which Australia fell 72 runs short of. Boycott was Man of the Match.

England had won three games from three and looked the form team until they came up against an impregnable batting display by West Indies in match 7 of the tournament in Brisbane, two days before Christmas. Andy Roberts bowled brilliantly for figures of 3 for 26 off his ten overs, working the Englishmen over with supreme line and length as well as that famous nasty bouncer he would produce after lulling batsmen into a false sense of security with a slower bouncer. Boycott stood firm as a rock against the assault, keeping a cool head throughout, slashing a short ball from Roberts over gully for 4 at one point. Mostly his innings was built on runs in the inner circle, hit with deft placement while combining in partnerships of 97 with Gower and 70 with Willey. The Yorkshireman was out for 68 off 117 balls with three 4s. England’s total of 217 was overhauled by the West Indies with several overs to spare, as Viv Richards and Gordon Greenidge both scored 85 not out. The West Indians looked to be on another level from England, while Australia were lagging both teams by quite a distance in this competition.

Sydney fireworks

Boycott had made his mark, but wasn’t yet finished. It was his fourth and final tour of Australia as a player. He was vastly experienced now and although this tour was arduous he was well up to the task, thriving. A particular comment in the middle of this long ODI competition summed up his form. It was before the start of play in Match 8 on Boxing Day 1979, England v Australia in Sydney, when Brearley and Chappell converged in the middle of the SCG for the toss. Chappell won and opted to bat. Immediately following this the TV continuity man sidled up to him and Brearley for quick comment. The England skipper was in a slightly dreamy mode – it was the morning after the English tourists’ christmas party, which he and the broadcaster had a chuckle about. Brearley was asked if he was happy with Boycott’s form.

“He’s played exceptionally well, certainly better than he feared, and better than a lot of people expected,” Brearley replied.

It was a notable day for Australia. The former captain, Ian Chappell, was back in the side after a brief time on the sidelines while he faced disciplinary action for arguing with an umpire in Sheffield Shield cricket, and also after reconsidering his international retirement. Streetwise ‘Chapelli’ helped his side break the shackles that the English bowlers had imposed on scoring. He blazed a top score of 60 while his brother Greg scored 52.

Later, under lights, England were chasing Australia’s target of 194 which started to look rather competitive when the tourists crashed to 179 for 6 after losing five wickets in the space of 27 runs. Hogg and Pascoe were the destroyers. Luckily for England, Boycott played the anchor and paced himself superbly. His vast powers of concentration were evident in the face of multiple distractions such as streakers invading the pitch, amid the constant roar from a speedway event next to the ground, not to mention the fireworks display that began when the event at the showground ended, shrouding the SCG in the mist for twenty minutes while the game continued. It was a crazy summer evening throughout which the opening batsman kept his cool.

Boycott’s innings contained few uncontrolled shots. He punished the slightest bad balls. One particular straight drive for 4 back past Pascoe had a ferocity to it that people didn’t normally associate with Boycott. Benaud, commentating at the time, noted a “tremendous whack”. There was another century stand with Willey before England’s collapse. The cause was almost lost. But with his Yorkshire teammate David Bairstow, Boycott methodically guided England to victory with five overs to spare. He was 86 not out, scored off 134 balls, including 6 boundaries. Another Man of the Match performance.

Finals

England qualified first for the finals and Boycott sat out their last two round robin games. By the time the best-of-3 finals came around it came as no surprise that the finalists from the World Cup would be squaring off again. First to Sydney on January 20th, 1980, for what turned out a thriller. The West Indies had the most explosive batting line-up in the world but a combination of Brearley’s savvy field placings, good bowling and excellent fielding restricted them to 215-8 batting first. Boycott was always going to be central to England’s chances of victory. Again he combined well with Willey in a second-wicket stand of 61 before he holed out to backward square leg off Roberts who was in devastating form and finished with 3-30 off his ten overs. Boycott’s 35 runs had been scored off 66 balls with just one boundary, the only time in the series that he failed to pass 50. Anyone facing the West Indian attack would have struggled to score prolifically. Roberts was miserly, Holding was sometimes unplayable and the towering Garner and Croft proved especially difficult to score off as their lengths and angles were often dangerous. England lost by 2 runs despite valiant late efforts by Brearley.

The second final two days later was at Melbourne where England batted first. Boycott was in control from the outset, spanking Croft with a straight drive for 4 before stroking Garner’s rising length through coverpoint for a beautiful boundary. He shared good partnerships with Gower and Graham Gooch, turning the strike masterfully in the face of hostile bowling. Making runs with a minimum of fuss, Boycott was, in the words of Lawry, unrecognisable from the player who toured Australia a year earlier. While he was batting, England were well set for a competitive total. Unfortunately, after Roberts dismissed Boycott, England’s innings lost momentum and they posted just 208-8 after 50 overs. In the end the West Indies made the series win look easy. Greenidge blasted 98 not out to guide the West Indies home with a few overs to spare, combining with Richards who scored yet another 50 and won the Man of the Series award. Boycott had scored 63 off 92 balls with 8 boundaries.

Stats

That summer, Richards was the most destructive batsman in the world. He was the leading figure in the West Indies’ emphatic 2-0 test series win over Australia. His form carried over into the ODI series when he was head and shoulders above every other batsman, although Boycott got closest, which wouldn’t have been on anyone’s bingo card before the series. So while Richards amassed 485 runs from 7 innings at an average of 97, Boycott had scored 425 runs from six innings at an average of 85, including four half-centuries. The next best average was that of Greenidge with 67.33 across 8 innings for 404.

To underline how well Boycott had done, we can also look at the strike rates. Here, Richards was well in front with 95.09, however one should note that he didn’t have to face Roberts, Garner, Holding and Croft. Of the six batsmen who scored more than 300 runs in the series, Boycott had the second best strike rate with 68.77, better than Chappell, Greenidge, Willey and Alvin Kallicharan.

Boycott had harnessed all his powers of concentration and the solid foundation of his batting technique in order to not just preserve his wicket and accumulate steady runs, but to build partnerships that gave England the best chance of competitive totals. He had extraordinary success with the solid Willey. The six partnerships between them during the series totalled 437 runs at an average of 72.83 per stand. With Gower, Boycott averaged 47.5 runs across 4 partnerships. Over the same number of partnerships, Boycott and Randall averaged 40, while Boycott and Gooch averaged 30. The Yorkshireman was the standout player in an England side with at least five all-time greats in it (including fast bowler Bob Willis whose turn it was to have a lean season).

Straight drive

The images of England’s players featured in the Scanlens card set are not the most exciting, especially compared to the flair of the West Indians or the sky blue panache of India. Perhaps it was the plain white uniforms that made England’s team seem a little dull, although Randall in mid-air cutting high through point always looked dramatic to me, and Bairstow’s high leap to catch a return throw nicely captured his plucky, fighting character that served England well when he played. But the best card of the England squad was Boycott and his gladiatorial straight drive. There’s something distant about the picture, perhaps like Boycott himself. Always somewhat remote from the mere mortals around him, Boycott still showed he was prepared to get stuck in and fight to the end.

The doubters would continue to have their say about his overall legacy, his selfishness and the dourness of his batting. Yet no one can deny that Boycott was capable of taking things to a higher level, of accelerating his batting attack. The 1979/80 series is proof. Four 50s and a century from six innings is testament not simply to Boycott’s great judgement of line and length, but powers of concentration too. Succeeding on the field, he was also seen to have enjoyed himself socially throughout the summer, as suggested by a photo of him, taking over the turntables from a DJ at a Sydney nightclub early in the new year. It was a fresh decade with new opportunities opening up for the professional cricketer, and here was Boycott dominating still. Rarely had he batted so positively against such high quality bowling, and certainly not in ODIs.

For Boycott, there would be more scandals to come in his storied career: ditching the national team in India mid-tour; revolt against the Yorkshire club management over the captaincy; taking a rebel England team to South Africa. He has always been someone who attracted controversy, perhaps even courted it. A great cricketing mind, ultimately when he was successful there was a good chance that the England or Yorkshire teams he was in would win, even if it did involve slow run rates. But during that southern summer of 79/80, Boycott had batted against the world’s best fast bowling attacks in pressure cooker environments and prospered. It was a fiery summer.

Leave a comment