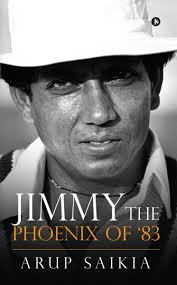

Jimmy: The Phoenix of ’83

Martin Chandler |Published: 2019

Pages: 154

Author: Saikia, Arup

Publisher: notionpress.com

Rating: 3 stars

I usually find the trickiest part of any review is the first sentence. Once I can find one I am happy with the rest generally flows easily enough. More than any book I can remember this one, from first time author Arup Saikia, has given me more trouble than most in that respect and, had I been writing this twenty years ago, there would certainly be at least a dozen discarded pages of a notebook to evidence my unsuccessful attempts to find something I was happy with.

The initial difficulty I had with Jimmy: The Phoenix of ’83 was in categorising it. Essentially it is biographical in nature, its subject being Mohinder ‘Jimmy’ Amarnath, but for a variety of reasons it cannot be described as a biography, although one thing reading the book did leave me with was the abiding impression that a biography from someone who knows Amarnath well, or an autobiography, would be a most worthwhile project.

In the little he gives of himself on the back of the book Saikia confirms that he is not a writer, but his detailed knowledge of the events he writes about amply demonstrate he is a lifelong cricket lover. Despite a lack of writing credentials as a former lecturer words are one of the tools of Saikia’s trade, and that is no doubt why the book is so readable, and one which I happily got through in one sitting on a quiet evening.

The book is, not unnaturally, going to appeal primarily to an Indian audience. A look at the recent Indian releases suggests that there is more interest there now in the history of the game than hitherto, and those who worship the likes of Virat Kohli and Jasprit Bumrah would do well to all read this. As well as telling the story of one of the more interesting Indian cricketers of the not too distant past Saikia also provides a concise and illuminating history of Indian cricket over the last forty years or so.

As for the man himself Amarnath was just 19 when he played his first Test, after which he had to wait more than six years for another chance. A well earned reputation as a fine player of fast bowling led to a regular place for three years until, after nasty injuries were inflicted by, amongst others, Imran Khan and Malcolm Marshall, he missed another three years. By the time the selectors turned back to Amarnath, in 1982, all batsmen were wearing helmets and Amarnath, hooking instinctively as always, enjoyed a remarkable purple patch which brought him five centuries in eleven Tests, all away from home, and all against the formidable pace attacks of Pakistan and West Indies.

Following his second coming in 1983 Amarnath was a member of the India side that came to England for the 1983 World Cup. An early Indian exit was widely predicted but, as all cricket followers know, Kapil Dev’s side proved all the critics wrong by beating red hot favourites West Indies in the final. Amarnath scored a stubborn 26 in India’s seemingly wholly inadequate total of 183. The Indians bowled very well in response but, by the time Amarnath took the ball, Jeff Dujon and Marshall looked like they might be about to take the game away from Kapil Dev’s side. Three wickets for twelve put an end to that however, and won Amarnath the man of the match award.

At that point Amarnath must have been feeling on top of the world and, with the prospect of Pakistan and West Indies visiting India, looking forward to extending his dominance over the world’s greatest bowlers. In the event in front of his own supporters he suffered the most astonishing slump in form that any major batsman ever has. He missed the third Test with Pakistan when he fell ill, but only managed innings of 7 and 4 in the first two Tests. Even that was comparative riches in light of what happened next. Six innings against West Indies, six dismissals and but a single run. It speaks volumes for Amarnath’s resilience that after that he recovered his confidence and went on to enjoy a further four years in the Test arena.

It would be fascinating to know Amarnath’s own take on his rollercoaster career, on how the pre-eminence of his father affected his thinking, and what he thought about the way his brother, Surinder, was treated by the selectors. What was his attitude to fast bowling? How did those injuries affect him? Saikia tells us next to nothing about Amarnath’s formative years, nor about his coaching career or his thoughts on the modern game. It is the absence of anything dealing with these questions that prevent Jimmy: The Phoenix of ’83 being a biography in the usual sense, but as a book that simply tells the story of Mohinder Amarnath’s cricket career it is certainly worth reading

Leave a comment