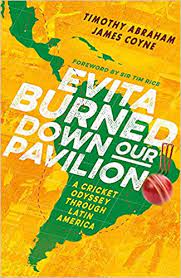

Evita Burned Down Our Pavilion

Martin Chandler |Published: 2021

Pages: 438

Author: Abraham, Tim and Coyne, James

Publisher: Constable

Rating: 5 stars

There was a time, and I will confess to being largely responsible for the idea, when we had a theory that any book that covered a ‘niche’ subject should not attract a rating of more than four stars. There was some logic to that, although exactly what it was now escapes me, but over the years the number of quality titles I’ve reviewed on obscure subjects has caused me to abandon such thinking. This is a relief because Evita Burned Down Our Pavilion, entirely appropriately sub titled A Cricket Odyssey Through South America, really is an outstanding book, and one that I am confident will be short listed for all of the major awards this year, and unless something really remarkable emerges in the coming months it will be a travesty if it fails to win at least one of them.

When I wrote my six monthly overview of forthcoming books in January I described Evita Burned Down Our Pavilion as a substantial history of the game in Latin America. In a sense it is, but I did the authors’ efforts a grave disservice in that comment, which implied the book would be something of an academic treatise, concentrating on dates, names, places and potted scores. This is why the the sub title is so apt, as the book is indeed an odyssey rather than a history, and is certainly not what I expected.

The odyssey involved the two authors arriving in Mexico in late 2015, and then travelling round Central and South America for the greater part of the next two years before returning home. Tim Abraham subsequently returned and the book has been in the course of preparation ever since – it has been well worth the wait.

In terms of how the book is written the ordering of it is geographical rather than chronological and, beginning with Mexico and finishing up with the pairing of Suriname and French Guiana, the authors take a chapter by chapter look at the countries of Latin America. All have some history as cricket playing nations, and Argentina in particular, but Brazil, Chile and Uruguay all have cricketing pedigrees as well and, in the interwar years in particular, were able to compete on level terms with some strong sides from England. A particular high point came in January 1938 when Argentina beat Sir TEW Brinckman’s XI by 222 runs. The touring side contained Bob Wyatt and Andrew Sandham, as well as three other men who had been capped by England.

Having referenced a particular match I should stress straight away that that is not something that Coyne and Abraham do, and there is not a scorecard in sight in the book, nor any statistics, tables or lists. The content of Evita Burned Down Our Pavilion is a purely narrative account, plus some excellent photographs and, for those of us who like cross referring things, a ‘proper’ index. Another welcome sight in a book of this type is the absence of any footnotes. There are, I appreciate, occasions when these are a useful tool but I do sometimes wonder whether they are really necessary, on the basis that if there is something an author wants to add then surely he should generally be able to work it into his prose without taking steps to break his reader’s concentration?

The strength of the book is the way its story is presented, in many places reading much more like a novel than a work of reference. It is clear that the ability to visit the locations that they write about has assisted Abraham and Coyne greatly, as have the local records and archives they have had the opportunity to consult and which they would undoubtedly never have seen without spending the length of time they did in South America. Above all however Evita Burned Down Our Pavilion is the engrossing read it is because of the information gleaned from local cricketers throughout the continent, not to mention those long retired from active participation, and the descendants of those who played the game in years gone by.

Without exception each of the chapters contains an account of the introduction of the game to the country concerned, generally by ex-patriate Englishmen, although a few Aussies play a role here. I must confess to having learnt a great deal from Coyne and Abraham about the extent of Britain’s commercial interests in Latin America in days gone by, and particularly in Argentina where at one stage, not unlike in Philadelphia, there were a handful of prestigious cricket clubs with excellent facilities – the incident which gives the book its title, in 1947, marks the start of a steady decline in the game’s fortunes there as the Peron era began.

Not unnaturally Coyne and Abraham end their odyssey with a look forward at the question of what the future holds for South American cricket. The picture they try to portray, and no one can blame them for this, is an optimistic one but even with their intimate knowledge of the game in the region it is difficult to escape the conclusion that the best days of cricket in Latin America are in the distant past. If they are then we do have at least have this comprehensive and hugely entertaining account of the idiosyncrasies of our great game as it developed so far away from its heartlands.

Leave a comment