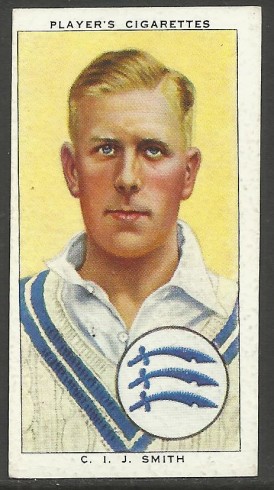

Big Jim Smith

Martin Chandler |

To state the obvious, batsmen are remembered for their batting, and bowlers for their bowling. There are all-rounders too of course, and those who rejoice in that description fall into three categories. There is that rarest of beasts, the true all-rounder, equally adept and memorable at either discipline; men like Ian Botham, Keith Miller and Mike Procter. Batting all-rounders are generally remembered for their achievements with the bat. Examples are Garry Sobers and Jacques Kallis. The bowling all-rounder is a man like Richard Hadlee, or Wasim Akram, undoubtedly capable with the bat, but whose legacy is largely comprised of his feats with the ball.

Occasionally a specialist bowler will produce a memorable innings. Jason Gillespie’s Test double century is a good example. ‘Dizzy’ has a couple of other Test fifties to his name, and an average of 18.73, but no one calls him a bowling all-rounder. Why make these self-evident points? The reason, of course, is an exception that proves the rule. Cedric Ivan James ‘Big Jim’ Smith is the man concerned. In a career ended by the outbreak of war a career total of 845 wickets at 19.25 is ample illustration of Smith’s quality as a bowler. With the bat there was a single century amongst a modest 4,007 career runs at 14.67 – figures of a bowler who can bat a bit as opposed to any sort of all-rounder. But it was always Smith’s batting that spectators wanted to see and that is what he is remembered for.

At first blush the popularity of Smith’s batting is all the more remarkable because he had only one shot* in his armoury, but then what a shot it was. In the words of one 1930s writer it was as sudden and as violent as the first crash of the big drum in a Wagner opera. Irrespective of line, length, pace, swing, spin or state of the match the front foot would be planted firmly towards mid wicket and a bat that Middlesex teammate Ian Peebles described as being five pounds** in weight would, starting in the direction of third man, be swung through the arc between there and mid on with such force that on occasion Smith had to adjust his footing to avoid overbalancing – other than that first movement those were the only circumstances in which he ever moved his feet. The back foot was always kept safely behind the popping crease. Not once in Smith’s career was he ever stumped.

It is worth pausing at this point to look at that description in light of Smith’s well earned soubriquet. He was six feet four and a half inches in height and had size 14 feet. As far as his weight was concerned in early 1936 that was seventeen stones and ten pounds. As they move into their thirties men of Smith’s build find it harder and harder to shift excess timber, and in a time where professional cricketers were not necessarily expected to be athletes nothing I have read suggests that Smith regarded his weight as a problem.

As is easy to imagine on those occasions the ball managed to get in the way of that booming slog it went a long, long way. If it hit the sweet spot of Smith’s bat it would sail over the boundary somewhere around midwicket. Had the Lord’s pavilion been located at mid on Albert Trott’s unique feat of clearing it would surely have been emulated. As it is Smith had to be content with the less well-remembered achievement of being the only man to clear the old grandstand, in 1937 striking a delivery from Lancashire fast medium bowler Dick Pollard way over Father Time. For anything other than the perfect contact the ball could go anywhere. Sometimes the sheer power of the stroke would take the mishit to the boundary anyway, and another not infrequent result was that the ball would be propelled more or less straight up for many a mile, bowler, fieldsmen and wicketkeeper sometimes all circling under it. Often of course Smith missed the ball completely.

Smith came from Wiltshire, in the days when being born in and living in a Minor County was a serious impediment to a career in county cricket. Both ESPN Cricinfo and CricketArchive describe his bowling as right arm fast, although I have found little in the way of contemporary reports to that effect. There is no doubt but that the slightly ungainly Smith shrugged off any initial impression of clumsiness when he began his smooth acceleration to the crease but, as his arm swung over and the height and strength in the shoulder added some nip of the pitch I suspect he was nearer fast medium. It is difficult to imagine a man of Smith’s build ever being truly fast, much like another at times ungainly Middlesex seamer who always appears in my mind’s eye when I think of Smith, Angus Fraser.

At 20, in 1926, Smith was recommended to the MCC and joined the Lord’s groundstaff. He bowled at members, played for the club regularly and was also released to play for his home county in the Minor Counties Championship. Over the next seven years he took 240 wickets for Wiltshire at a cost of barely 15 runs each. In 1933 Jack Durston retired. He had opened the bowling for Middlesex since 1920 and was the tall man of county cricket. For 1934 Smith had finally got his residential qualification and could play for Middlesex, so they still had the biggest man in the game opening the bowling for them.

The story of how the qualification was finally achieved speaks volumes as to the attitudes of the time, and doubtless about Smith’s personality. The rule was that if a man was not born in his county he had to live there for three years before acquiring a residential qualification. Smith started to live in Middlesex in 1929, which would have made him eligible to play in time for the 1932 season. The problem was he forgot to tell Wiltshire what he was doing, and Middlesex obviously had no system for checking whether he had. There was no objection raised by the Minor County, but rules were rules and Middlesex and Smith had to wait another two years.

No pace bowler has ever outshone Smith’s first summer in county cricket. In all First Class matches he took 172 wickets at 18.88. The only two quick men with slightly better averages, both of whom bowled many fewer overs, were Harold Larwood and Bill Copson. The other five men in front of him were all slow bowlers, and only Tich Freeman, the prolific Kent leg spinner, took more wickets. To put Freeman’s labours in context he bowled 350 more overs than Smith, and paid more than five runs per wicket more for his scalps.

The Australians visited England in 1934 for the first meeting of the game’s traditional enemies since ‘Bodyline’ had inflicted such deep wounds in 1932/33. Smith’s attitude to fast leg theory can be demonstrated from an admonishment he once gave Bill Edrich. The eldest of the Norfolk brotherhood is remembered as a batsman but in his early years was a very fast if somewhat erratic and therefore dangerous bowler. Smith had no time for a burst of short pitched deliveries that Edrich served up to Gloucestershire wicketkeeper Andy Wilson at Lord’s in 1938 and didn’t hold back in letting Edrich know.

Despite being in his first season in 1934 Smith must have come close to England selection. He had the advantage of his home ground being Lord’s, so he was always going to get noticed, and in the game against the tourists he sensationally dismissed both of the famous Australian opening pair, Bill Woodfull and Bill Ponsford, without scoring. His 4-99 was a more than creditable return in an innings that recovered thanks largely to 160 from Donald Bradman. That he was in the selector’s minds was confirmed by his selection for the tour to the West Indies that winter. It wasn’t a full strength England side, only Ken Farnes of the pace bowlers who had played against Australia making the trip. That said over the season as a whole Smith had out performed each of those selected for the Ashes ahead of him; Gubby Allen, Bill Bowes, George Geary and left armer ‘Nobby’ Clark.

Smith enjoyed his time in the Caribbean, and played in all four Tests. His debut was a remarkable match. England captain Bob Wyatt won the toss and after heavy overnight rain had no hesitation in asking West Indies to bat. Smith opened the bowling with Ken Farnes, the tallest combination ever to do so for England. There were no wickets for Smith but his teammates dismissed the home side for 102. There was a duck for Smith in England’s reply of 81-7, Wyatt closing whilst still behind as he recognised the need to get West Indies back in whilst the pitch was still spiteful. In turn West Indies declared early, on 51-6 with Smith taking 5-16. In this game of cat and mouse Wyatt sent Farnes and Smith into bat in the hope they would take up some time while the wicket returned to normal. England did get home in the end, but Smith completed a pair, the first England batsman since Fred Grace to do so on debut – the next was to be Graham Gooch in 1975.

Following England’s victory in the first Test West Indies hit back and won two of the other three matches to take the series 2-1. Smith was never so penetrative again as in the first Test. Skipper Wyatt felt he should have cut his pace a little in order to give the ball a chance to swing, but there was still a return of 11 wickets at 29.90 so his tour was by no means a failure. In the colony matches there were a couple of fifties, the lack of swing naturally being of assistance to the likelihood of the famous slog drive connecting. There was also another excursion up the batting order in the third Test. After winning the toss and batting Wyatt and David Townsend spent a painful hour and a half over an opening partnership of just 36. On Townsend’s dismissal the skipper called Smith in to give the innings some impetus. This time the move paid off. Smith was only at the crease for ten minutes, but he struck three sixes as his cameo of 25 had the desired effect.

After he returned from the Caribbean Smith continued to be a highly effective force in the County Championship although he never exceeded his tally of wickets of that debut season. It is said that the out swinger did not work quite as well again after 1934, and that the occasional in ducker he could produce deserted him. If that was the case then Smith’s record would have been very special indeed without those lapses. His averages for the three summers from 1935 were still highly impressive at 18.21, 15.08 and 17.47 respectively which placed him 12th, 6th and 6th in the national averages. He cannot have missed selection for the 1936/37 Ashes trip by much, and his form in early 1937 was such that he was finally picked for a home Test. Sheer weight of wickets brought him into the side for the second of three Tests against the 1937 New Zealanders. Smith took a couple of wickets in each New Zealand innings, and scored 21 and 27 in his inimitable style, but it was all change for the final Test as the selectors decided to look at others. Smith didn’t get the call again.

To return to where I began the real joy of Smith was his batting, but a big innings was a rarity and therefore something to be cherished. There were just fifteen half centuries in his entire career, all of them entirely ‘in character’. The first came at Lord’s in 1933 when Smith was playing for MCC against Yorkshire. The visitors had an unpleasant shock when they were dismissed for 147, and were doubtless relieved to have MCC’s reply at 71-8. They did indeed end up with a first innings lead, but not before the last two wickets added 56, all but four of them scored by Smith. Yorkshire won easily enough in the end, but cannot have much enjoyed those frenzied few minutes.

Rather more crucial was Smith’s first fifty for Middlesex, 53 in a win against Derbyshire at Lord’s in 1934. The eventual victory margin was only 84, so without those runs and Smith’s seven wickets the game may well have been lost. That was the only fifty that summer but it was followed that winter by the two in the Caribbean. The first was 83 against Barbados. For once Smith couldn’t quite monopolise the scoring. He came in at number eleven to join the great Walter Hammond who was unbeaten on 281 when Smith was finally dismissed. They had added 122, so Smith comfortably outscored England’s premier batsman. The second was 54 against Trinidad, a valuable innings as without it the colony would almost certainly have beaten the tourists.

There were two fifties in 1935. Yorkshire were the victims again at Lord’s in June. This time when Smith appeared they probably realised that 32-8 might not be the end of the Middlesex resistance, and it wasn’t, Smith scoring 57 to lead his side if not to respectability then at least to 108. In July of that year Smith played one of his most famous innings, against Kent at Maidstone. After rain interruptions Middlesex needed 221 to win. Promoted to number six Smith scored what at the time was the joint fastest fifty ever scored, in fourteen minutes. It is possible the innings took only twelve deliveries. What is certain is that he took 49 from three of Freeman’s overs, and that on the stroke of time the last Middlesex wicket fell with them just six runs short of their target.

The first of Smith’s three fifties in 1936 was another innings that almost but not quite propelled Middlesex to victory. His 50 was part of a strong lower order recovery from 75-6 in Middlesex’ first innings, but in the end Warwickshire got to their target of 218 with their last pair at the crease. Just over a fortnight later Smith, again at Lord’s, scored a 26 minute fifty against Somerset. It wasn’t a game changer, as Middlesex won by an innings, but included two sixes and ten fours. Wisden did mention he gave more than one chance – no comment is made on how easy they were.

Finally in 1936 Smith held up Yorkshire again. This time they had Middlesex at 70-8 when Smith came out and scored 56 out of the 57 added by the last two wickets. There was no speed record, but only because three of his four sixes were out of the ground necessitating lengthy delay while balls were found. Unsurprisingly Smith’s effort didn’t prevent an innings defeat, but it would have left an indelible mark on the Scarborough crowd.

As if to confirm his status as a tailender Smith did not pass fifty in 1937, but the following summer was his most productive, with 736 runs and four half centuries. Most spectacular of all was his 66 against Gloucestershire at Bristol. It took Smith just 18 minutes to score 66, and his fifty came up in 11 minutes. There were eight sixes and two fours. Other than in contrived circumstances no batsman has ever broken that record. The shell shocked Gloucester side were beaten by an innings.

Smith’s innings against Sussex at Hove took a comparatively pedestrian 35 minutes. Chasing 300 to win Middlesex were 90 short when skipper Walter Robins decided to give the innings some impetus and promoted Smith to six. He was rewarded with an innings of 57 that all but settled the issue. Earlier in the season Smith had gained a taste for the Sussex bowling, taking just 20 minutes to score 69 against them at Lord’s to help achieve an innings victory in Fred Price’s benefit match. His other fifty in 1938 was 51 for MCC against Cambridge University.

In June 1939 Middlesex defeated Lancashire at Old Trafford. A somewhat subdued Smith contributed 52 with the bat, with just a single six and a mere four fours. His 7-55 including his only First Class hat trick was probably a bigger factor in the win however. Against Nottinghamshire at Trent Bridge in August Smith scored 72 out of 105 added by himself and George Hart for the ninth wicket in just forty minutes to set up an innings victory.

With war clouds gathering in August 1939 the county game entered its last month for the best part of seven years. For Smith it was the last month of his First Class career and a visit to Kent a week after his knock at Trent Bridge was the 202nd of his 208 First Class matches. Middlesex were still in the hunt for the title and stand in skipper Peebles faced a tough decision on the first morning. He won the toss, but there had been overnight rain with the sun getting stronger as the morning rolled on. In the end Peebles decided to bat.

Peebles was a leg spinner good enough to win 13 England caps and, briefly in 1930, raise hopes that Bradman’s nemesis had been found. He was nothing special as a batsman though, and was batting at eleven against Kent. The score was 242 when the ninth wicket fell and Peebles, reasonably pleased with his side’s progress, hoped to add a few more with Smith, who had only just arrived himself and was unbeaten on four.

Smith played the only way he knew of course. Peebles wrote later of his realisation that it might be Smith’s day. Kent seamer Alan Watt produced a fine over, the ball consistently missing Smith’s bat and, narrowly, the stumps. Then just as the crowd had been resigning itself to accept it wasn’t Smith’s day the first big hit came off, the ball clearing the famous old lime tree at the Canterbury ground for six – had it no more than touched the top most leaf it would just have been four.

Peebles described his own role thereafter as; I plied the ‘dead bat’ but was by no means idle. Backing up was a matter of gaining sufficient elbow room to take violent evasive action. To avoid loss of limb, or even life itself, one had to resort to the zooming vertical climb or the undignified crash dive, whilst averting collision with a bowler and umpire similarly employed.

There was no injury however. The ball hit nobody, instead it whined and hummed to every point of the boundary, not excluding the screen directly behind the striker. Smith was on 32 at the close and next day, dealing almost exclusively in boundaries he got to 101 before Peebles was dismissed. It was his first and last century. The crowd loved it, all it would seem except the former Kent captain Gerry Weigall who described the innings as a prostitution of the art of batting. He went to his century with a square cut – no one had ever seen him attempt such a shot before.

At the end of the 1939 season Smith’s contract, worth £350 a year to him, ended. He was only 33, and particularly in that era had a number of years in the game to look forward to. Throughout the war Middlesex did pay their professional a small retainer, and when peace returned the 39 year old was invited to rejoin the staff for the 1946 campaign, but decided against it.

Since his marriage in 1934 Smith had been based in Harlestone in Northamptonshire and he stayed there throughout the war. He did some building work, using skills acquired from his father, and also spent some time working in the local ironstone pits. From 1941 he supplemented his income with an engagement at Windhill in the Bradford League. He then moved to Yeadon in the same League and spent three summers there. In the first and last years his side won the league, and he paid less than ten runs each for his wickets.

The Smith family moved to Lancashire in 1946. The summer before had seen Smith sign with the East Lancashire club who played in the Lancashire League. There were three more years for Smith as a professional cricketer. The final summer of 1948 was a little disappointing, injury hampering Smith’s bowling and at 42 he looked to the future. With his wife he took the licence of the nearby Millstone Public House at Mellor. He was to remain there for 22 years, during a significant part of which he was also involved in coaching at Stonyhurst College.

There was some amateur cricket after 1948, but a broken left fibula a couple of years later put an end to Smith’s active participation in the game. After passing fifty on fifteen occasions in his seven seasons for Middlesex in the First Class arena, in twelve summers in the leagues Smith did so just once. The lesser standards and smaller grounds would suggest Smith’s returns with the bat should have improved, but clearly the inferior wickets did not suit his style. Less surprising was that the one half century he did post took him just fourteen minutes. Interestingly the start of his career, when he played for Wiltshire, also brought but a solitary half-century.

*One writer accepts it should be said there were one and a half shots, the half being what appeared to be a swat to anything that was pitched so short on the leg side that the slog drive was not possible.

**Others have repeated this but the source in each case is almost certainly Peebles and seems likely to be a deliberate exaggeration. A brief biography in The Cricketer in 1936 described Smith’s bats as being between two pounds six ounces and two pounds eight ounces. The same article had to disappoint those who subscribed to another ‘Big Jim’ myth, that he needed a new bat every time he went to the crease. The man himself confirmed that he had got through the rather more modest total of six in 95 visits to the crease in the preceding two seasons.

Leave a comment