Before The Storm

Gareth Bland |

In February 1977 Pakistan arrived in the Caribbean to embark on only their second tour of the region, the first having taken place some 18 years previously. Expectations were high, Mushtaq Mohammad’s team having just toured Australia and creditably left its shores with honours even. West Indies, too, were expectant: fresh from a 3-0 series annihilation of England during the previous summer, they could justifiably lay claim to being the planet’s second greatest team after Australia. Revolution was afoot, though, and Clive Lloyd’s team would soon be catapulted onto an even higher plane as World Series Cricket meant that this was – with the exception of two Tests in early 1978 – the last time that a full stength West Indies would play officially mandated Test cricket in the Caribbean until the spring of 1981 when Ian Botham’s England arrived. The ensuing five Test series in early 1977 was full of attacking cricket, tension, bravery and, for the most part, good will between the two teams. In the words of Wisden the series was “an intensely interesting series between two evenly-matched teams”. Within a year the peace of international cricket would be shattered as the cricket war which broke out between Kerry Packer and the game’s administrators took hold. But for one Caribbean summer, however, the attention was focused on what took place out on the field. The ebullient, knowledgeable Caribbean cricketing public could not possibly know that they would not see their first team playing Test cricket at home for another four years. They were not the only supporters who would miss their team at full strength, though. For Pakistan, too, would experience major defections once the World Series Cricket experiment got under way. Presciently in the light of the revolution about to come, this tour also witnesed the inaugural one-day international played on Caribbean soil, too.

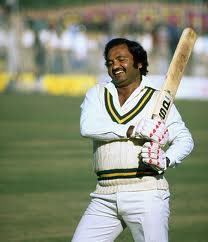

On 18th February 1977 Mushtaq Mohammad and Clive Lloyd walked out on to the middle of the Kensington Oval ground in Barbados. Mushtaq opted to bat on winning the toss and his judgement appeared vindicated as his team ran up a total of 435. The West Indian pace battery had been rejigged to account for the loss of Michael Holding and Wayne Daniel through injury. Their replacements for the series were instant successes. The local boy, the 6’8″ Joel Garner and the the brooding Guyanese, Colin Croft, would go on to form the original quartet of pace men with both Holding and Roberts. Garner at 24 and Croft, 23, were both menacing from the outset. Pakistan’s first innings total was built on the imperious 88 from the opener, Majid Khan, and a more swashbuckling 117 from Wasim Raja. Majid, then 30, was at the peak of his powers. Particularly adept at the hook, he had taken on Lillee in Australia wearing only his trademark white sunhat. Fired up, the great fast bowler had vowed to knock the hat off its wearer’s head. By the series’ end, Majid had won the battle with Lillee and subsequently presented the Perth man with his hat as a gift. Neither Majid nor Wasim was afraid to go after the quick bowlers in the Caribbean either, which in the days prior to the helmet seems astonishing. Given that Croft and Garner were bolstered by the presence of Hampshire and Antigua’s Andy Roberts, it is all the more admirable.

That West Indies compiled a total of 421 in reply was due in no small part to the destructive counter-attacking of Lloyd who smashed his way to 157 with 21 fours and 3 sixes. At 183-5, however, the home team had been precariously placed and in danger of having to follow-on. At this point Deryk Murray joined his captain to add 151. Imran himself, who along with Sarfraz had reduced the West Indies to 183-5, attributes the Windies’ recovery to the decision of Mushtaq to take the new ball. With the old ball all the West Indies batsmen had been dismissed thanks to controlled swing and seam bowling. With the new cherry the ball came on to the bat at greater pace which played into Lloyd’s hands. The left hander was then able to club the Pakistani bowlers around the Kensington Oval. As Imran explained:

“Sarfraz asked me to tell Mushtaq that the new ball would only give the batsmen breathing space. A succession of Pakistani captains, including Mushtaq, couldn’t take Sarfraz’s unorthodox and unpredictable approach to the game and distrusted him. So I went up to Mushtaq and passed on Sarfraz’s logic. But he would not listen. After all, if we were bowling so well with the old ball, what wonders might we perform with a new one? It didn’t work. The new ball came on to the bat, and on the bare pitch would neither swing nor seam. Lloyd opened his shoulders and knocked us over the ground”

With West Indies just 14 runs in arrears Pakistan went in to bat once more. Immediately Roberts, Croft and Garner ran riot to leave Pakistan reeling at 158-9. Incredibly, the match was to see-saw yet again as the momentum swung back Pakistan’s way. This time Wasim Bari joined Wasim Raja in a last wicket stand of 133. Bari struck 10 fours in his 60 while Raja hit 5 fours and 2 sixes in his 71 before being the last man out. West Indies target was 306 to win. At 142-1 they looked well set for victory thanks to a partnership of 130 between Fredericks and Richards. When Fredericks was dismissed at 142 and Richards was third man out at 166 the innings disintegrated. Imran, Sarfraz and Saleem Altaf got Pakistan right back in the game and seemed poised for an improbable victory as West Indies slid to 237-9. However, Roberts and Croft managed to hang on to take West Indies to 251-9 and the safety of a worthy draw. Although Pakistan were disappointed not to win the Test, cricket was the ultimate victor here. As Imran said some eleven years later in 1988, “The first Test at Bridgetown was one of the finest I have ever played in. From start to finish it was completely unpredictable”.

The West Indies, though emerging as genuine contenders to Australia’s crown, still displayed some of the lax and unprofessional tendencies that were in evidence during their Australian tour in ’75-76 and which would be eradicated in the coming years. In Pakistan’s second innings 291 as Wasim Raja rode his luck during the last wicket stand with ‘keeper Bari, Wisden observed “At this point, their cricket fell to pieces. Their fielding and catching were shocking and Murray allowed 29 byes to pass”. The side was heading towards maturation, though, and the pace trio of Roberts, Croft and Garner were distinctly menacing. It has always been conventient to attribute the ascent of the West Indies to their hot-housing under Packer. True, the introduction of Dennis Waight as fitness supremo and the fostering of a group mentality Down Under took the unit to new heights. It does, however, ignore the role that county cricket played in allowing West Indies players to hone their skills during the seven day a week English domestic season. Roberts, after all, had been terrorising county batsmen since 1973 with Hampshire and had famously scalped the young Ian Botham in 1974. Richards, Lloyd, Greenidge, Murray and Van Holder of this team were all county regulars, too. At this juncture in the international game with Holding and Thomson injured, Roberts was the most lethal bowler in the world. Not only was he fast, he was also developing variations so subtle that they were indiscernible by grip or through changes in approach or delivery stride. On this tour, as the Pakistani batsmen would note, the infamous “two speed” bouncer would cause both physical and psychological difficulties.

For the second Test in Port-of-Spain Pakistan omitted Javed Miandad and were missing Sarfraz through injury. Opting to bat first, Mushtaq would rue his decision as his team were shot out for 180 with Croft’s career best 8-29 doing the damage. As in the first Test Majid and Wasim Raja were largely responsible for their side’s total, with 47 and 65 respectively. Bowling with speed and lift on an uncertain surface, together with his inimitable delivery stride which took him wide of the crease, Croft met little resistance from the Pakistani batsmen. Mushtaq, as Imran noted, was exhibiting signs of shellshock against pace, having received some rough treatment in Australia on the previous tour. Mushtaq’s brother Sadiq also looked shaky as did Zaheer, who only played two Tests on this trip. More worryingly, the redoubtable Asif Iqbal, so lion-hearted against high speed in the past, seemed out of sorts, too. Unusually, Asif seemed to have no answers to the problems caused by Croft. In reply, West Indies hit 316 as they opened up a lead of 136 against Pakistan’s spin-heavy attack. Pakistan’s second innings 340 came as a result of an excellent opening stand of 123 between Majid and Sadiq as the latter at last came good with 81. Once more that dasher, Wasim Raja, flayed the bowlers with 84, hitting two more sixes and seven fours. Needing 205 to win, West Indies were given the ideal platform of an opening stand of 97 from Fredericks and Greenidge. At the end Kallicharran and Lloyd carried the team home to a six wicket victory despite the best efforts of Saleem Altaf and Imran.

On the South American mainland for the third Test in Guyana, Pakistan showed their mettle after having been shot out cheaply again on the opening day. As Croft had run through their batting for 180 in Trinadad in the previous game, here they staggered to 194 after Garner, Croft and Roberts had taken four, three and two wickets respectively. For once, Wasim Raja failed with Imran’s 47 and Mushtaq’s 41 being the significant contributions. After Fredericks was dismissed cheaply in reply, West Indies’ batsmen contributed most of the way down the order. Greenidge made 91, Richards, 50, Kallicharran 72 and Shillingford 120 to take the team to 448. With a deficit of 254 Pakistan needed to fire on all cylinders in their second knock. After Sadiq had retired hurt with the score on 60, Majid and Zaheer rehearsed for their 1979 World Cup semi-final epic by taking the score on to 219 when “Zed” perished for 80. Compensating for his first innings duck, Zaheer looked more like his old self as he struck 13 boundaries along the way. Majid’s brillant Test best 167 came to an end with the score on 304, although Pakistan were still not done yet. Haroon Rashid made 60, Asif and Imran 35 a piece, with Sarfraz and Wasim Bari each contributing 25. Pakistan had totalled 540 and batted for two days. Signifiantly, Majid had drawn the venom from Roberts who finished with bowling figures of 45-6-174-3. Needing 287 for victory, West Indies set about the Pakistani bowlers. Although well short of the required total Greenidge in particular was harsh on both Imran and Sarfraz, each of whom went for over 6 runs per over. Looking back, Imran argued that Greenidge “was a butcher and at his peak”. With West Indies 1-0 to the good and two Tests still to play the best was yet to come in this absorbing, intriguing series.

With no Antiguan Test match yet on the horizon – that would not come until 1981 – West Indies and Pakistan convened once more in Port-of-Spain for the fourth match of the rubber. Lloyd again put the opposition in to bat. As ever, Majid, with 92, proved the mainstay. His 14 fours and lone, imperious six were struck off 180 balls. The captain seemed to be finding his feet, though. Unsure and shaky in the the first couple of Tests, Mushtaq struck 121 here, with 14 fours, during important partnerships with Majid (108) and later on, Sarfraz (68). Pakistan’s 341 gave them a good platform on a pitch which was expected to take turn. With the slow left-armer Iqbal Qasim supplementing the leg spin of Mushtaq, Pakistan’s attack was balanced between spin and seam. Imran finished with 4-67 while the captain followed his century with 5-28 as West Indies were dismissed for 154. From the relative comfort of 73-0 West Indies fell apart, losing all 10 wickets for 81. At 95-5 in their second innings Pakistan were rescued, once more, by Wasim Raja with 70, this time hitting 6 fours and 3 sixes. Mushtaq continued his marvellous all-round contribution with 50, which was backed up by Sarfraz who also struck a half-century. With real grit and aggression Pakistan had once more turned things round to total 301-9. Needing an improbable 489 for victory the home side never looked up to the challenge as Mushtaq, Wasim Raja and Sarfraz each took 3 wickets to skittle the Windies for 222, inflicting upon them a 266 run defeat.

Revelling in their victory, this was a Pakistan team that contained more than its fair share of characters. The Punjabi speaking street philosopher, Sarfraz Nawaz; the young, pugnacious son of Karachi, Javed Miandad, and, let us not forget, this was a touring party which represented not only the elite of Pakistani cricket but also the elite of its society, too. From Multan in the Punjab came Wasim Raja, son of a senior civil servant. Alongside Wasim in the middle order was the languid Asif Iqbal, nephew of the former Indian Test cricketer Ghulam Ahmed. Throw into the mix the dynastic make-up of the team and we have a heady brew indeed. Captain Mushtaq reigned over his younger brother Sadiq in the opening slot. Accompanying Sadiq at the top of the order was Majid Khan, Oxbridge educated cousin of his fellow Pathan, Imran. In back to back series against daunting opposition, Mushtaq and his eclectic assortment of gifted cricketers had concocted a successful and entertaining blend.

With all square the series was set to be decided at Jamaica’s Sabina Park ground. On what was expected to be a lightning fast surface conducive to pace and bounce, this was the very ground that had seen India capitulate a year earlier when Bedi declared India’s innings to protect the tailenders. Lloyd again won the toss and decided to bat this time round. The West Indian first innings was dominated by Greenidge’s even 100. With 15 fours and 3 sixes he was particularly harsh on Imran and the incoming Sikhander Bakht, included at Iqbal Qasim’s expense for the pacier conditions. On that first evening Pakstan began their reply in the hope of negotiating Roberts and Croft for a few overs before the close. What happened had major ramifications for the remainder of the match as Roberts bowled with a ferocity unmatched even by his earlier standards. Imran picks up the story:

“We went in to bat forty minutes before the close on the first day, and before the day was over, 280 might as well have been 500. Andy Roberts bowled four extremely quick overs at Majid, and it was apparent that Majid was quite unnerved by this. The shock waves of those overs reverberated through the dressing-room. Majid had handled pace better than anyone else throughout the tour, both in Australia and the West Indies, and seeing him rattled had shaken our entire batting line-up”

Things did not markedly improve on that second morning and Pakistan had Haroon to thank for them being able to reach 198. His aggressive 72 gave the innings a varnish of respectibility. In reply, West Indies second innings was built around a brilliant opening stand of 182 from Fredericks and Greenidge. Lloyd made 48, Murray 33 and Holdford 37 so that West Indies closed on 359. The game was effectively up for Pakistan as they needed an unlikely 442 for victory. Croft quickly reduced them to 32-3 to make matters merely academic. However,late in the series Asif Iqbal produced a controlled gem of an innings with 135 and, yet again, Wasim Raja hit hard to make 64. Pakistan’s 301 looked around par in the light of their earlier poor start. And so an involving, dramatic series had finished with West Indies victorious 2-1. Incredibly, it would be a further eleven years before the two teams would meet again in the Caribbean, by which time, of course, much would have changed.

The clash in the Caribbean summer of 1976/77 was an important one in the evolution of each team. For the home side,the future had been signposted. Although Fredericks would not go on too much longer, the template for the batting line-up had been set so that the spine comprised Greenidge, Richards and Lloyd. Greenidge would soon be joined by his younger compatriot, Desmond Haynes, as the composition of the top order would remain essentially the same. In terms of the bowling attack Roberts, Croft and Garner would soon be augmented by the returning Rolls Royce himself, Michael Holding. Probably even more than in the previous Test series against England, away from home in 1976, this series demonstrated what sustained, hostile pace could achieve against even top class batting.

In this series Croft topped the averages with 33 wickets, backed up by Garner with 25 and Roberts, the Daddy of them all, with 19. Garner’s whirling, windmill action sported here and during the early WSC encounters would eventually be smoothed out, developed and adjusted with economy of movement in mind. Roberts would continue to develop his box of tricks, Croft would get nastier and Holding would develop in the coming overseas seasons into probably the fastest bowler ever. When the WSC circus rocked into town in the spring of 1979 the Caribbean crowds could have been forgiven for thinking that Lloyd’s team was the official West Indies version. There being no Test cricket in the region that summer, the Packer-minted Supertests against Ian Chappell’s Australians represented the only form of “international” cricket around the islands that year. So completely had Clive Lloyd’s outfit usurped Kallicharran’s recent Indian tourists in profile and charisma, that it was virtually a given that they would morph back into the “official” West Indian squad for the upcoming World Cup in England.

For the tourists their Australian and West Indian tour of 1976/77 represented “an important watershed in the evolution of Pakistan’s cricket psyche” according to Javed Miandad. If they had not done so before the cricket watching world had taken notice of this burgeoning Pakistani team. In Australia they had shared the three Test series 1-1 and had taken the series to the final game in Jamaica against the West Indies. As Javed remarked “we had stood up to the best in the world and it marked our coming of age”. As with their opponents who were signed up by Kerry Packer en masse, Pakistan were depleted to the extent that they effectively fielded a reserve team until 1979. Majid Khan, Zaheer Abbas, Mushtaq Mohammed, Asif Iqbal, Imran Khan and latterley Javed Miandad all signed up for World Series Cricket, and so the 1976/77 series presents a paradox. What the Australian public gained during the next two seasons the rest of the cricket watching world lost. An insipid and below par Pakistan presented easy pickings for the England of Gower and Botham in 1978, but how would they have fared against this particular vintage? This was, after all, a team that had thrilled Australian and West Indian cricket watchers in two tense and even-handed battles.

For West Indies, of course, their Packer vintage and official teams developed in what can best be described as parallel cultures, until the eventual return of Lloyd’s men from isolation in 1979 saw them supplant their “official” brethren in the West Indies team completely. This was a coup that arrived just in time to see them lift the World Cup in England for the second time at Lord’s in June 1979. Before the storm of the cricket war engulfed the game later in 1977, Pakistan and West Indies played out an absorbing series that proved to be a fitting end to an epoch in Test cricket and which foreshadowed a new era altogether.

Brilliant article about a fascinating series. It was barely covered in the British press at the time, so I wasn’t aware of it until years afterwards. One of the hugely significant WI series in the 1970’s, the other being the tour of India a few years earlier when Richards, Greenidge and Roberts first emerged.

Comment by wpdavid | 12:00am GMT 8 November 2012