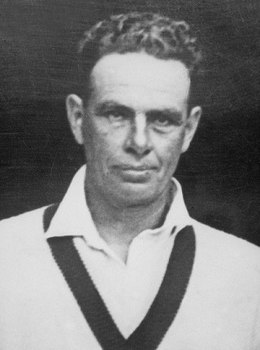

An Aussie Who Defied Anno Domini – ‘Dainty’ Ironmonger

Martin Chandler |

Bert ‘Dainty’ Ironmonger comes very close to a whole clutch of records, without holding any on his own. He was, if you accept his date of birth as 7 April 1882, at 46 years 237 days, the fourth oldest man to make a Test debut, and the second oldest to play in a Test (50 years 327 days). As a bowler his Test average is, using the qualification of having bowled at least 2,000 deliveries, the ninth best of all time at 17.97. By economy rates he is the fifth best, conceding just 1.69 runs per over. Amongst Australians he holds all those records on his own, with the exception of the lowest bowling average where he is bested by JJ Ferris and Charlie Turner. All of those above him bar Sydney Barnes began their careers in Victorian times, and Barnes’ last Test was before the Great War.

A man from an era where it was common for cricketers to excel in only one discipline of the game, and not to worry too much about improving their performances in the others, Ironmonger was a classic example. He was a brilliant purveyor of left arm orthodox spin, but his batting and fielding were rather less impressive. With the bat he did, just, manage to score more runs than he took wickets, but a career average of 5.95 speaks for itself. His only shot was a swipe in the general direction of the covers, and AG ‘Johnny’ Moyes described his appearances with the bat as a gesture to convention. There is also a famous story of Ironmonger’s wife telephoning the dressing room, being told he was about to go out to bat and electing to hold the line. It is a delightful story, marred only slightly by the fact that the Ironmongers did not have a telephone until after his cricket career ended.

As far as Ironmonger’s fielding is concerned it is that aspect of cricketing endeavour that was apparently responsible for him being christened ‘Dainty’. His best known achievement in the field came in the final Test of the Bodyline series when he held on to a catch hoisted towards mid off by Harold Larwood who, at that stage, had progressed to 98 after being sent in, much to his irritation, as nightwatchman the previous evening. The identity of Larwood’s catcher caused much amusement at the time, although to be fair to Ironmonger he had always had a reasonably safe pair of hands. What he did lack was mobility, and he never ran very far, and when he did get moving he wasn’t too keen on bending down, and would habitually stop the ball with his boot.

Ironmonger’s date of birth was, during his playing career, sometimes stated to be as late as 1887, a misconception he was happy to leave in place. He was the youngest of ten children, and brought up near Brisbane. As a child he lost the top of the index finger of his left hand in an accident with a chaff cutter. A quick thinking sister who plunged the injured digit in flour in order to staunch the flow of blood did Australian cricket a favour. The wound healed and the ball could be spun off the stump with a flick of the wrist that gave the Ironmonger action an unusual appearance. He was never no balled for throwing, but the slight disquiet that attached to the action was said by some to be the reason he was never invited to tour England.

In terms of pace Ironmonger was certainly not slow. He took a run up of around nine paces and did not flight the ball a great deal. As his economy rate suggests Ironmonger was not a man prepared to buy a wicket, and if the pitch was unhelpful he would wheel away and put the batsmen under the cosh and wait for them to make a mistake. He was fortunate in that his physical deformity allowed him to get at least some turn on even the most unforgiving surface, and if the wicket helped him he could be lethal.

It was 1910, at which point he was employed as a labourer on the railways, that at almost 28 Ironmonger was given a First Class debut for Queensland against Victoria. A last minute replacement two days before the game began he took three wickets in a disappointingly heavy defeat. That match was the last of the three games Queensland had scheduled for that season but, eight months later, he was selected, again only after others pulled out, to play against New South Wales. The Queenslanders recorded a famous victory, and with three good wickets at a personal cost of 99 runs Ironmonger certainly contributed. It was not, however, enough to impress the selectors and he disappeared from view.

Two seasons then passed without Queensland looking in Ironmonger’s direction, and he didn’t get the call again until early December of 1913 when, yet again to cover for last minute withdrawals, he was called into a side due to play in Melbourne and Sydney. The Queenslanders lost both matches by an innings. In the first Ironmonger took just a single wicket for 99 runs, but bowled with such skill that he was later invited by the Melbourne Cricket Club to join them as a ground bowler. In the following match against New South Wales he had his first five wicket haul, at a cost of 138 runs. Ironmonger made the move south in January and went to Tasmania in March with Victoria where, with 20 wickets in two matches, he played a big part in two big wins.

So it came to pass that in the 1914/15 season Ironmonger, by then almost 33, made his Sheffield Shield debut. After the first match one journalist reported he was not really dangerous, but by the end of the five match campaign he had 32 wickets at 17.12 and Victoria had regained the Sheffield Shield.

By the time peace returned Ironmonger was 36 although he was no longer employed by the Melbourne club. Whilst he had been there he had supplemented his income with bar work and had in time himself moved into the licensed trade. In 1918/19 he was back in the Victorian side but when, the following season, the Shield resumed he played only in the first match of the campaign. Initially he was injured but when fit again was not picked. The selectors were still playing fast and loose with him the following year, dropping him for one of the four games and only selecting him for another at the eleventh hour after they were let down. At the end of the summer the main Australian party were on their way to England, but Ironmonger accepted an invitation to tour New Zealand with what amounted to a second team. He took 45 wickets at 13.17 and also contributed an unbeaten 36 to a hectic last wicket partnership of 50 scored in twenty minutes. He was, apparently, given a number of lives. It was the only time in his career that he scored more than 20.

After the New Zealand trip Ironmonger, by now a married man, left Melbourne for Sydney in search of new opportunities. He stayed less than two years before returning to Melbourne. By then in his forties the Victorian Cricket Association could not be criticised for looking towards younger players, particularly as they had just begun selecting off spinner Don Blackie, the same age almost to the day as Ironmonger, and who had made an excellent if belated start to his career. There was however in all probability an element of irritation and parochialism as a result of the move to Sydney. In any event it was to be nearly four years before, in 1924/25, Ironmonger reappeared twice, not unusually again as a result of others being unavailable. In the second of those matches, against the touring MCC side, he became only the third Victorian bowler to take a hat trick. He reappeared in the first Shield game of 1925/26 as well, but was then dropped and not recalled despite the bowlers who were selected being on the wrong end of some substantial totals.

Whatever may have been going on in 1926/27, when Ironmonger was left out in the cold completely, he was then called up for the first Shield game of 1927/28. He was retained, for only the second time in his career, for the entire programme and Victoria lifted the Shield once more. Only New South Welshman Clarrie Grimmett took more wickets than Ironmonger. Blackie, with 31, matched his state teammate.

In 1926 England had finally won back the Ashes for the first time since the Great War. The Australians had some fine batsman, and the debut of Don Bradman was just around the corner. The bowling was a source of much concern however, so much so that Ironmonger was picked for the Test trial played in advance of the 1928/29 series. A particular surprise was that despite failing to take a wicket in that match Ironmonger was selected for the first Test, although contemporary press reports indicate he bowled well.

England won the first Test by the small matter of 675 runs. For Ironmonger there were figures of 2-79 and 2-85. His victims were all front line batsmen, Douglas Jardine, Patsy Hendren, Herbert Sutcliffe and Walter Hammond. The Sydney Morning Herald wrote that on the first day Ironmonger was always dangerous, steady in his length and variant in his flight and turn. His was the bowling display of the day; it was one of stamina as well as guile. In the match he bowled as many as 94.3 overs, and he got the nod for the second Test as well. To further limit Australia’s options the first Test proved to have been a last hurrah for Jack Gregory who injured a knee in attempting to take a return catch from Larwood. Blackie was called up in his place and Australia’s three main bowlers, Ironmonger, Blackie and Grimmett were 46, 46 and 36 respectively.

The Australians lost the second Test by eight wickets. Ironmonger took 2-142 in 68 overs. He was still in the 13 for the third Test but, on the eve of the match, was left out for Queensland’s Ron Oxenham, a right arm medium pace bowler and a more than useful batsman. The rains came and on the one wicket in the series on which Ironmonger would have thrived he wasn’t even playing. He did not return to the side for the fourth or fifth Tests.

Realistically the only Test tour which Ironmonger was ever going to go on came in 1930. Australia, thanks to the remarkable deeds of Bradman coupled with a better than expected display from their bowlers, won back the Ashes. There can be little doubt that Ironmonger would have been effective in England, but he was not selected. As noted much earlier some suggest that doubts about his action were a reason for his omission. A look at the contemporary accounts however suggests otherwise.

In his book on the 1928/29 series, The Turn of the Wheel, former England all-rounder and still at that stage Surrey skipper, Percy Fender, described Ironmonger’s performances in the two Tests he appears as being steady, but that he did not look threatening. It is a markedly less enthusiastic description than that of the Sydney Morning Herald, although in relation to that particular day Fender did acknowledge that Ironmonger kept the batsmen quiet. There is however no mention of any disquiet over his action.

In 1929/30 Ironmonger took 38 wickets at 20.07. The other 47 year old, Blackie, took 36 at 21.83 and Oxenham, by now 38, 24 at 19.33. None of those three made the party in 1930. In his book on the 1930 tour Pelham Warner expressed the view that Blackie and Oxenham were strong candidates for selection, and concluded their age was the reason for their omission. He makes no mention at all of the claims of Ironmonger. Fender also wrote a book on the 1930 series and in his introduction referred to a general approval amongst the Australian press of the party that was selected, subject to a few pressing the claims of Blackie and Oxenham, the latter seeming to find favour with Fender himself. Again there is, oddly in light of his 1929/30 record, simply no mention of Ironmonger. The only Australian to write a book on the tour, journalist Geoffrey Tebbutt, says little of the make up of the side other than to stress its youth, something he seemed to welcome. For him too there was no mention of Ironmonger, nor for that matter Blackie or Oxenham.

After their youthful side had regained the Ashes Ironmonger doubtless thought his Test career was over, having comprised just those two matches in 1928/29. In fact there were to be a dozen more appearances, beginning with four of the five Tests in the home series against West Indies in 1930/31. The visitors were beaten in their first match by New South Wales, but gave a decent account of themselves. Then however they came up against Victoria on a pitch that was tailor made for the veteran Ironmonger who took 5-87 and 8-31, the best of his career, in a victory by an innings and 242.

The selectors did not choose Ironmonger for the first Test, won comfortably by Australia by ten wickets. All but one of the West Indian wickets were taken by Grimmett and Alec Hurwood, the other being the first of Bradman’s two Test wickets. Paceman Tim Wall was disappointing and was replaced by Ironmonger for the second Test. The selection did not go down well in some quarters, critics citing both Ironmonger’s age, and his relative lack of success in the past at Sydney.

Each of the next three Tests were won by Australia by an innings and the decision to invite the men from the Caribbean began to look a poor one. Ironmonger was his usual reliable self and really came to the fore in the fourth Test on his home ground at the MCG where he took 11-79. He followed that with a twelve wicket haul against South Australia before taking his season’s tally to 68 at 14.29 in the final Test, unexpectedly won by the visitors to give the scoreline some respectability.

The summer of 1931/32 saw South Africa tour Australia for a second time, more than twenty years after their first visit. Their very first match introduced them to Ironmonger and, batting on a good wicket, they were clearly not troubled by him as his first innings figures stood, at one point, at 0-61. The rain came however and the nature of the game changed, those figures ending up at 5-87 and a second innings 5-21 to carry Victoria to victory.

In the first three Tests against South Africa Ironmonger took nine, four and seven wickets as Australia strolled to a 3-0 lead. At that point he was dropped, a 23 year old New South Welshman, Bill Hunt, being selected to bowl orthodox left arm spin in his place. The press, generally, greeted the decision with some hostility particularly former internationals Charlie Macartney, ‘Stork’ Hendry and Arthur Mailey. From a previous generation Clem Hill supported the decision, stating that Ironmonger was past his prime and a successor must be found. In the event Hunt went wicketless and left the Test arena never to return. The selectors, given the match was to be played at the MCG, restored Ironmonger to the side for the final Test, won by Australia by an innings despite their being dismissed themselves for only 153. Ironmonger’s figures on the difficult wicket were remarkable, 5-6 and 6-18, and he finished the series with 31 wickets at just 9.55 runs each.

After two straightforward series victories the following season, that of 1932/33, brought England to Australia, and trouble. The ensuing Bodyline crisis remains the most controversial series of Test matches ever played. By now 50 years of age Ironmonger was playing in the early tour match when the Englishmen’s fast leg theory was first wheeled out, and he was in the squad for the first Test. He was left out of the final eleven and watched England’s ten wicket victory from the sidelines. Recalled for the low scoring second Test at the MCG Ironmonger went wicketless in the first innings, but took an important 4-26 in the second as England slid to defeat. There were also two memorable contributions with the bat. In his first innings Ironmonger scored only four, but they came from a textbook cover drive from the bowling of Larwood as a result of which, on his return to the pavilion, he unsurprisingly questioned out loud what all the fuss was about. He was run out for nought in the second innings, but not before he had made sure Bradman had time to get to his century.

Unfortunately for Australia that second Test was their high point of the series and England eased to victory in each of the three remaining matches. Ironmonger played in all three and he got through plenty of work, 212 overs with his trademark accuracy. The 15 wickets he took in the series were not however enough to make a difference and, finally, the last rites at the MCG marked the end of Ironmonger’s international career. It was doubtless of little consolation to him, but he did at least take the two wickets that fell during England’s successful fourth innings pursuit of 164 for victory.

Early in the 1933/34 season the Victorian Cricket Association held a joint benefit match for Blackie and Ironmonger. The match was not well treated by the weather, but more than 40,000 people turned up, clearly demonstrating the pair’s popularity. The only blight on the match was that Ironmonger missed much of it with a knee problem, and although he put in a full season his fitness was now suspect and, despite many knowledgeable writers calling for his selection for the 1934 touring party to England it was not to be. Australia regained the Ashes, but on their return skipper Bill Woodfull was quoted as saying, there were times when I longed to have Bert Ironmonger to fling into the attack.

Having taken just 14 wickets at 32.21 in the previous First Class season Ironmonger waited until Woodfull’s side returned before announcing his retirement from the First Class game before the start of the 1934/35 season. The veteran was not seen again in Victorian colours but a year later he did join the first Australian side to tour India, a mix of those who had already retired or were otherwise not going to be needed for the Sheffield Shield. It was a long tour, lasting from October to February, but Ironmonger played in only three of the First Class matches, and had to spend some time in hospital in Hyderabad with typhoid. He was at least sufficiently recovered to return home with the rest of the party, and he did take 5-70 in the second innings of his final First Class appearance, the first of the four matches against All India, won by the Australians by nine wickets.

On his return from India Ironmonger went back to his job as a gardener with St Kilda Council, a job he did until 1952 when, the truth about his age finally coming to light, he was obliged to retire. A non-smoker Ironmonger rarely drank and the healthy outdoor life meant that he enjoyed a long retirement, with plenty of opportunity to attend at the MCG as a spectator. He was 89 when he died in 1971.

The nickname “Dainty” was apparently given to Ironmonger by Vic Richardson during the 1920-21 Australian tour to New Zealand. Before that he was known as “Darkie” because of his deep tan and dark curly hair, so Richardson’s intervention was very welcome!

Comment by Max Bonnell | 2:49pm BST 2 October 2018