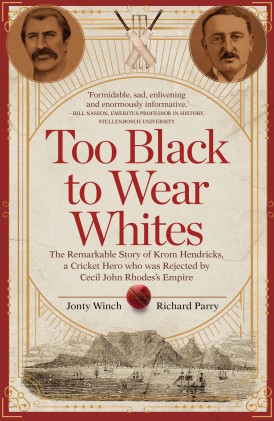

An Appointment with Krom Hendricks’ Biographer

Rodney Ulyate |

Let’s begin with who Krom Hendricks was, and why he’s so important.

Okay. Well the difficulty is that, of course, Krom Hendricks is a figure that we know very little about in concrete terms. We have little evidence of his own family, his background and his context apart from the image of a man who is clearly an important figure both for South African cricket and in the context of the evolution of the South African political structure. Hendricks was a Cape fast bowler in the 1890s. His background, as I suggested, is somewhat unclear, although we do have a number of details. He’s part St Helenian, part Dutch in origin. He grows up in the Bo-Kaap, in the Malay culture—a strong sports culture—and he clearly has a great deal of talent. He shoots to prominence in the early 1890s when he plays against Walter Read’s touring team in 1890.

The Hendricks Saga really begins with the 1894 tour of England, which is where I first heard of him. Long before reading your book, I’d gone to the effort of tracking down that very dignified letter he wrote to The Cape Times in January of that year, refusing to tour England as a glorified “baggage man.” (So far as I can tell, Too Black to Wear Whites is the first book to quote that letter in full.) What I didn’t appreciate until reading your book was that Hendricks’s struggles with the Cape authorities extended well beyond that tour: At every point in his career, at every level of the game, he was thwarted and insulted. Perhaps you’d like to give us a précis of the saga.

Yes, that’s absolutely true. The real story about Hendricks is the longevity of the struggle between him and the powers-that-were at the Cape. He was fighting against racism on two fronts.

On one level, he was fighting the Cape’s political structure: Cecil Rhodes, who was prime minister from 1890, and his parliamentary private secretary William Milton, who ran South African cricket, were keen to develop a racialised structure within South Africa—what they called “segregation” at the time, a forerunner to apartheid.

Secondly, he was fighting against a virulent social racism, based on social Darwinism and some of the ideas that that were rampant in English society in the late Nineteenth Century, which saw race as a fundamental basis for Empire, and indeed the basis for life as a whole.

Now, Hendricks struggles with this first of all in 1894, when he’s omitted from the touring team on the instructions of Cecil Rhodes, and as you say, he writes to The Cape Times. There’s a suggestion made that he might be able to go as baggage master and play the odd game—to make sure that his inferior status is specifically recognised. Of course, he’s too proud a man for that, and has the dignity to say, “You must be joking. I’m certainly not going in that capacity.”

And then, of course, his struggle continues. In 1896, he’s selected by the Transvaal to be part of the squad to try out for the Test Match against Lord Hawke’s tourists. He’s prohibited by Milton from going to the Transvaal, so he’s actually blocked from attending, and that’s the last chance he gets to play at international level. He’s not selected for any representative teams in the Western Province, except for one or two “All-Comers against Western Province Cricket Club” matches, where he proves his abilities and shows himself a star player, and terrorises the powers-that-be from 22 yards.

He continues his struggle after the Anglo-Boer War (1899-1902). In 1904 the issue is raised again, and it’s around the question of whether he should be allowed to be a club professional. He’s initially refused this right in 1897, and then raises it seven years later again—really for the last time—and in each case he’s thwarted by the Cape cricket establishment. They won’t make an exception for him. As far as they’re concerned, the fact that he’s played for a Malay team prohibits him from playing as a professional and playing club-class cricket in South Africa. So he’s written out of the cricketing structure.

The important thing to stress about Hendricks is that if he’d been merely a very good cricketer, his case wouldn’t be much more than a sad footnote in South Africa’s fraught cricketing history. What elevates it to the level of tragedy is that he was rather more than just a good cricketer. He was a truly great one. You quote reams of testimony from a great many fine players who came into contact with him, including seasoned Test stars like George Hearne and Billy Murdoch, who thought the world of him. There’s a remarkable unanimity of testimony on this point: in fact, that he was almost the greatest fast bowler they’d ever faced. The only other bowler in the whole history of the game who matches this—who had virtually all his contemporaries rating him the best—would be George Freeman, the great Yorkshire fast bowler of the 1860s and 1870s. But what makes these claims even more impressive in Hendricks’s case is that he was deep into his thirties, well past the traditional fast bowler’s peak, when they were made. So it seems to me that he ought at the very least to be spoken of in the same breath as other great bowlers from this era—the likes of Fred Spofforth and George Lohmann and Charlie Turner. There are, of course, qualifiers and caveats to be made, but the tragedy of Hendricks is that he never got the chance to vindicate these claims before a big audience and at the highest level.

Yes, exactly. That’s precisely the tragedy. He never got to live out his destiny. It was the beginning of the way in which, owing to politics, sports could not reflect what South Africa essentially was. He was spoken of, as you say, almost unanimously, as the fastest bowler, and by many as the best bowler, that they had ever faced. But of course he had a relatively small engagement with foreign players. Certainly within the South African context he was recognized as the fastest bowler around. And indeed his results, in the chances he did get to play in high-quality cricket, show just how good he was. On one occasion, for example, in a first-league club match that he did get to play, against Claremont, he bowled nine overs, nine maidens, no runs and took nine wickets.

Must be some kind of record.

Pretty astonishing statistic. He was clearly several standards above anybody else. He bowled against English touring sides in the nets, and as you say, he’s getting on a bit in the 1890s. He’s born in 1857, so he’s in his late thirties when Lord Hawke brings the team over in 1896. And Tom Hayward, who’s the star Surrey player, and the best batsman on the tour by some distance, faces him in the nets. At the end of the tour Hayward is interviewed in The Cricket Field and asked who the best bowler he faced on the tour was. Hayward doesn’t think of any of the South African bowlers that he faced in matches or in the Tests, which is where one would expect him to go, but says, “In fact, the best bowler I faced in South Africa was Krom Hendricks. But I didn’t get a chance to play against him; I just faced him in the nets.” And that gives some indication of the esteem in which Hendricks was held, and in fact just how good he was, that he was able to impress somebody like Hayward merely through a net session.

I mean, it seems pretty well established to me—your book does a fantastic job of proving this, I think—that he was South Africa’s first great cricketer, of any race.

Yes. That’s certainly our view: that he’s a considerable distance ahead of any others. All things being equal, had he been able to perform on the global stage, he would have been South Africa’s greatest cricketer of the Nineteenth Century. Jimmy Sinclair, I guess, is the next cricketer to that. Sinclair was a different player, of course. But for sheer ability and for sheer natural talent, I think Krom Hendricks probably would have outshone even Sinclair.

We don’t know much about Hendricks’s personality. Your book, given the limitations of the source material, is less a biography of the man than a history of his war with the establishment, or rather the establishment’s war on him. But you do furnish a number of very suggestive clues. He seems to have been a complicated fellow, and to have struggled somewhat to reconcile his dignity and his personal integrity with his cricketing ambitions. You write, non-judgmentally, of his efforts to “pass” as a white man. Perhaps you’d like to elaborate on that.

Yes, I think one needs to look at the whole question of race in South Africa in its context. Race has become ossified in a particular way in the Twentieth Century. It was much more fluid in the Nineteenth, especially for somebody like Hendricks, whose background was, as I suggested at the beginning, somewhat debatable. It’s not even clear that Hendricks himself knew what it was. For example, we know that his mother comes from St Helena, which suggests, in South African parlance, that she was “black.” People who came from St Helena tended to come over as black indentured workers in the 1880s and 1870s. On his father’s side, I don’t think even he knows who his father is, although he says on a number of occasions that he’s Dutch—and in fact in 1904 says that both of his parents are European. Now, this is this is another interesting development, because his mother, when she finally dies in 1909, is actually buried as a European.

So Hendricks is trying to succeed on the cricket field, as you say, with a great deal of dignity and integrity, and to fight a particular struggle with the authorities, who have decided that he is “black.” Now, this is a subjective judgment. Nobody actually knows—maybe Hendricks himself doesn’t know—but they’ve decided that he is black, and have simply treated him as such, and simply written him out of his opportunities. Whether he is black, or is not, doesn’t actually matter. What matters to Hendricks, of course, is to have a life in South Africa which allows him to have a family, for that family to do as well as they possibly can, and so on.

In the Twentieth Century there’s a kind of parallel process going on for Hendricks. He plays cricket for Crusaders in the City Cricket League, what was known as a “coloured” league, from 1904 all the way through to 1915. He’s still playing in his late fifties. So he comes out, essentially, as a coloured. He says, “Okay, that’s my community. Those are the people I’m engaged with. That’s how I define myself on the cricket field.”

But beyond the cricket field, of course, he doesn’t necessarily define himself as “coloured” in those specifically hard racial terms. As I suggested, his mother is buried as a European, as is Hendricks himself in the 1940s. And most of his children are “European,” but not all. One of his daughters, Winifred, is considered to be “coloured”—and indeed by the 1950s there’s an issue around whether she can be buried with her husband in the same graveyard, because of course they’re of different “racial groups.”

But that’s when race becomes a specific classification which determines all aspects of life. It doesn’t necessarily do that in the early years of the Twentieth Century and in the late Nineteenth, and as a consequence of that it’s about finding one’s place in a very fluid environment. Part of the history of Hendricks is really the history of how race becomes essentially the hard line, the rigid framework, within which all life is developed and operated. But that’s a slow process, and Hendricks is very much part of this confusing maelstrom of people and activities and engagements where a person’s race is not able to be established or classified, nor indeed particularly relevant—except on the ideological level of Cecil Rhodes.

One of the challenges of writing a book like this, on an era like this, must be the language. Most of your sources are written from the perspective of these ideologues, and it must be quite difficult (as I think I showed in the awkward way I phrased my question) to avoid speaking in these terms yourself, or taking certain of their priors for granted.

Yes, that’s right. It’s very difficult to be able to take that context and reduce it into terms which not only make sense in the current area, but also provide the right degree of dignity and analysis. There were a number of issues in writing about Hendricks: first of all around the fluidity of the situation and trying to establish what happened within the context of that fluidity, knowing that the rigidity of the response to Hendricks within what was a fluent situation and how one balances that out; and then secondly, of course, there was the problem of sources and material and how you write history. As historians most of us are used to being able to go into the archive, sift through the material, make fine judgments on what’s in the material, deal with things that are contradictory, and come out with stuff that makes sense and allows one to move the story forward.

In the Hendricks case there’s so little core material that it’s extremely difficult really to assess what Hendricks is at any given moment and what’s really happening to him. And one of the real interesting points about this book, I think, is the challenge that the lack of primary materials presents. We have, as we were discussing, Hendricks’s letter to The Cape Times. To my knowledge that is the only material we have from Hendricks at all. We have nothing else that he’s written. We have nothing else that he’s even reported to have said (apart from a few comments in The South African Review). There’s almost nothing at all that we can directly attribute to Hendricks. We don’t have members of his family who’ve spoken to him. We don’t even have members of his family who remember him. His descendants, while they’re clearly very interested in who he was (as they would be) also simply don’t know who he is. There’s no one yet who’s come up and said, “Ah, Krom Hendricks! I remember William Henry Hendricks very well!” Nobody has. Nobody does.

So we were writing a book within an extremely isolated context, trying to develop the significance and the character of an individual about whom we have very little hard evidence, but a great deal of evidence which points to what he was likely to be and what his context was, and I think the reason that we were able to write about him is that there is so much peripheral material (newspaper reports being the most obvious). And he is such a “name,” and he has such recognition at the time—he’s clearly so significant—that we were able to write about him, and were able, I hope, to come out with conclusions which essentially reflect where Hendricks was and how he moved over time and what happened to him over that 25-year period. The longevity of his cricket career, and indeed his political career—although he would never have seen himself as having a political career, but really he did—provides a really clear window into South African society.

Just as an index of how badly needed this book was, I logged on to CricketArchive just this morning to look him up. Their entry for “Krom Hendricks” describes another player entirely—one of his contemporaries. I really should write to them and get that fixed.

Yes! Just on that point, I first wrote about Hendricks—he first came to my attention—in 1992. I thought at that stage, with the anniversary of the first-ever South African visit to England (1894) coming up, that it might be interesting to have a look at that tour. And, of course, once you start reading about that, Hendricks jumps out at you. What I discovered was that there were a number of reports about Hendricks, but they all had different views on who he was. There were several Hendrickses in the Malay match. There was “A. Hendricks,” who opened the bowling with him—

It’s Armien Hendricks whom they confused on the website for Krom.

The reason they confuse him is that Armien Hedricks in that Malay match was actually the guy who took the wickets. He took four-fer, whereas Krom Hendricks took one for 29, so people automatically assumed it must have been Armien. In Rowland Bowen’s book on cricket, which came out in 1969 or 1970, and has the first significant mention of him in a proper cricketing history, he talks about “T. Hendricks,” who also played in that game, but he was a batsman! So there’s been a lot of confusion. The first article I did, in 1992, was called “The Real Mr Hendricks,” and it was about who this guy was. That was the first thing that motivated me: to establish what I could about this clearly extremely important and significant figure in early South African cricket. And just to nail down who he was took us a long time.

Once we nailed down the fact that it was Henry Hendricks, it was then a matter of trying to find out who he was—find his birth certificate, and so on—and we finally did that. We established the family background. It was a difficult process. But we were able at least to provide the human side to the cricket, because that human side—who he was—is so fundamental to the cricketing side. In a lot of cases you can separate those things. You can write cricketing biographies which are about the cricket. But in Hendricks’s case it’s really all about him.

Hendricks, of course, wasn’t the only victim of the Hendricks tragedy. You—and of course by “you” I intend a second-person plural, including your co-author Jonty Winch—write very movingly of the fate of Hendricks’s champion, one Harry Cadwallader. My friend and colleague Aslam Khota has suggested to me that he’d make a fascinating supporting character in any movie about this saga.

Yes, he would! Jonty’s done quite a lot of work on two journalists who were really significant in this period. One was Harry Cadwallader, who was the first secretary of the South African Cricket Association (SACA), in 1890, and took on Hendricks’s case. He was Hendrix’s most significant supporter leading up to the 1894 tour, and as a result of supporting Hendricks effectively lost his job as secretary of SACA, lost his job as potential manager of the tour, and in fact died a few years later in penury.

The second journalist was a guy called Charles Finlason, who played for South Africa in 1888/89, when Aubrey Smith brought his first lot of tourists over. Finlason and Cadwallader were bitter rivals. Both worked in Kimberley, but for different papers. In fact, Finlason played for South Africa while he was a journalist—while he was writing about it—which created a massive controversy during the 1888/89 tour. Cadwallader was his opponent in that controversy.

Cadwallader also set up SACA. He knew that it was necessary to try and bring the various parts of South Africa together. South Africa was at the time a number of different countries. There was the Cape, which was a colony; the Southern Republic of the Transvaal, which was an independent country, under Paul Kruger; the Free State was independent as well; Natal, too, was a separate colony; and so on. And there was massive rivalry both across the subcontinent and also within the Cape, between Kimberley, Port Elizabeth and Cape Town. And so a lot of the struggles in the cricket world are essentially economic and political struggles as well.

Cadwallader and Finlason were very much involved in that process, taking different sides. Finlason was a South African, reflecting South African interests—a “South Africa First” character: “These guys coming over from Britain know nothing about Africa,” and so on. Cadwallader a was more of a Brit, more on the imperial side. Rhodes, of course, found itself on the South African side in the end. The politics of all of that provide a really fascinating background to all of this.

But Cadwallader himself (to get at last to your question!) was an extremely interesting character. He clearly had a great deal of empathy for what Hendricks was going through. Cadwallader’s mistake was that he fell in the middle: If, as seems likely, he was involved in the discussions over Hendricks and the “baggageman” compromise, he would almost certainly have lost Hendricks’s sympathy, having gone over his head, having not negotiated it properly with him.

At the same time his support for Hendricks meant that he got hammered by people like AB Tancred, who at the time was described as the “WG Grace of South Africa.” He was the Test opening batsman, and a Transvaal lawyer. He had a great deal of engagement in this, and was very dismissive of Hendricks, calling him “impudent” and whatever. So what happened to Cadwallader was simply that he fell in the middle.

But yes, in terms of a film, he’d be a delightful counterpoint to Hendricks’s particular struggle, because he’s got his own particular struggle. But they’re all within the same political environment.

A word in conclusion about the project of which Too Black to Wear Whites forms a part. I think even the most casual reader of cricket literature will have noticed in recent years the wealth of new material we’re getting on South Africa’s cricket history—the extraordinary efforts of the likes of Andre Odendaal and Krish Reddy and Bruce Murray and Ashwin Desai to widen the lens beyond the traditional white-establishment game. I wasn’t aware, before I read the acknowledgements section of your book, that this was an organised, collaborative effort. I’d love to know more about the genesis of the project and how you feel it’s progressing.

Well, I think “organised” is maybe a little bit strong, but certainly it’s been a project which was developed and is building very much on the work of Andre Odendaal and Ashwin Desai and so on. The collaborative bit has been partly with Andre Odendaal, who’s obviously just finished volume two of his history of South African cricket, but also a collaboration that we developed partly in South Africa, partly in the UK, which has kind of worked in parallel to Andre’s collaborative project, which is itself the history the history of cricket. I can’t remember exactly how far he’s got in Divided Country, but I think it’s around the Sixties.

The collaborative project that we were working on was to develop a series of essays—and it’s a slightly more academic approach—around the genesis of the relationship between sport and politics in South Africa. It’s less a history of the cricket, more a history of the way in which the relationship between cricket and politics has been fundamental to the development of South African society and the South African state. There have been a number of people involved in that particular collaboration: Jonty and I, of course, and others such as Bernard Hall, Dale Slater and Jeff Levitt. We’ve published two volumes so far: one called Empire and Cricket, which was published by Unisa in 2010 or 2009, and a second volume which was published a couple of years ago, called Cricket and Society in South Africa, which takes us up to about 1970 We’ve brought together a number of scholars in the area and tried to produce this history: people like Raf Nicholson, who’s written on women women’s cricket in South Africa and the D’Oliveira issue; Patrick Ferriday, who’s written stuff on it, too; and so on. We’ve tried essentially to provide a transformationist history, some background and context to what the history was about. I did some stuff, for example, in the second volume on Frank Roro and black cricket on the rand and the mines, and the relationship between labor on the mines, strike action and cricket. It’s quite a it’s quite an interesting and contradictory process around this question of migrant labor and stable workforces and the significance of cricket in that environment.

But it started off with an essential idea—and it really comes from Hendricks: Here we have somebody who is clearly an outstanding cricketer, and yet he’s deprived of opportunities for political reasons. It’s remarkable just how close the political environment is to the cricketing environment. The political leadership and the cricketing leadership are essentially the same thing. William Milton is the most obvious example, being right-hand man to Rhodes, the governor of Southern Rhodesia, and also captain and selector of the South African cricket team, essentially running the whole operation. Of course he’s not the only one. There lots of people in that situation, and if you go to the governors of Southern Rhodesia, for example, they’ve all played cricket, and they’ve all been involved in the Western Province Cricket Board, and they’ve all been guys who’ve said no to Hendricks. So there’s a really very close relationship there.

On the other side, when you look at the African leadership, coming out of Lovedale and the mission schools, all of those guys are also politicians: Bud-M’Belle and Sol Plaatje in Kimberly, and the guys in Cape Town, and so on. They’re the people who are involved in the origins of the ANC—what was initially called the South African Native National Congress. They were behind the political missions to the UK in the 1900s, when the UK was basically selling them down the river to allow the Union of South Africa to be formed on a racially-based franchise, with the exception of the Cape.

So the people who play cricket and who run cricket are very closely connected in these stages to the people who run politics, and this just tends to be the case all the way through. That’s what that project was about: to chart that relationship, to see how it was established and maintained.

And where the project goes from here: in principle, of course, we we’re looking at the possibility of doing a post-1970 volume, taking us to the beginning of the end of isolation. It becomes much more difficult when you get closer to the current moment, so I’m not quite sure how that will go, but there’s a discussion about us doing that. It’s meant to be a kind of a parallel project to what Andre is doing with his History of South African Cricket Retold. The goal is to provide a context to that very necessary cricket history.

I’m working myself on a book at the moment about the politics behind the English cricket tours to South Africa, and the role played by the MCC between 1889 and 1964, what’s going on behind the scenes, and what’s going on in the cricket as well. I’m trying to draw out all of those strands and essentially provide a transformational history of South African cricket.

So I’ll have to wait a little longer for your biography of Frank Roro. He’s the other major figure in this area of whom I’m desperate to read a full length treatment.

I’d love to do it. I think we’d both be keen to do this. It was a bit like Hendricks. The literature which allows you to pin down anything other than a very vague bio of him is very hard to obtain. There’s just almost nothing. Nothing that tells you where he came from and who he was, and why he was so good. But he clearly was. That whole area—the mission-school background, the Kimberley mine labour, the Rand mine operations—is really critical, I think. Somebody needs to work on that. We don’t know nearly enough.

Right. Well, thank you, Richard. That’s more than enough to fill a tea interval. I’m sure readers will be very grateful.

Yeah, it’s a pleasure, Rodney. It’s great to talk to you. Thanks very much.

This is tremendously important work.

Incidentally, reclaiming these stories is not limited to South Africa – a lot of this reminds me of difficulties I had researching my book on Jack Marsh. In fact it’s possible that at some point in the 1890s, Hendricks, Marsh and Tom Richardson were the best fast bowlers in the world.

Comment by Max Bonnell | 11:31am BST 16 September 2020