The Private Don

Dave Wilson |Published: 2004

Pages: 266

Author: Wallace, Christine

Publisher: Allen & Unwin

Rating: 4 stars

Don Bradman, on his retirement from playing cricket, would spend two hours a day on letter writing. Rohan Rivett was a journalist and editor of Adelaide newspaper The News from 1951-1960, when he was fired by Rupert Murdoch. While editor there he had commissioned Bradman to report on the 1953 Ashes for the paper, as a result of which association a close friendship developed over almost a quarter of a century of postal correspondence, until Rivett’s sudden death in 1977. Rivett’s widow Nancy donated these letters to the National Library of Australia which in 2003 decided to make them available to the public. It is these letters which are reviewed and summarised for The Private Don, a book by Christine Wallace.

The author states in the opening chapter, entitled The Letters, that the correspondence gives an insight into aspects of Bradman’s character which he had carefully shielded from the public after his retirement from cricket in 1948, and which allowed his detractors to level all kinds of accusations at him, presumably safe in the knowledge that Bradman would not be inclined to give his version of events.

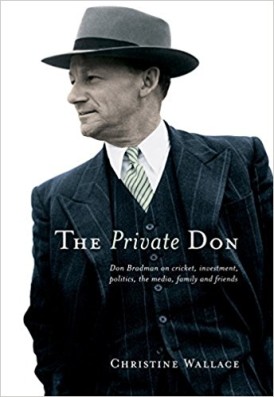

It has to be said that first impressions of the book are excellent. There are great photos throughout, particularly at the front of the book where Bradman is seen carrying his own equipment including four or five bats, as well as walking in overcoat and hat and sporting a wry grin while several young boys walk beside him gawping in awe. The first chapter also opens with the wonderful line: “Limelight is illumination of the most unreliable kind”.

The letters are summarised in about half a dozen chapters, entitled Cricket, Investment, Politics, The Media, Family & Friends and finally The Private Don, in which the author gives her opinion on what the content of the letters tells us about Bradman. Each chapter is prefaced by a quote from the letters, such as ‘. . . my political philosophy does not support any party but only the personal things which I believe in’ which kicks off the chapter on Politics.

Though I’m not the best-read member of CW staff, it’s fair to say that Bradman had not given us much to digest from his own pen following his retirement save an autobiography in 1950, so I learnt quite a bit about the great man. For example, he was quite the analyst, as noted in his discussions with Rivett on scoring rates – “I have taken out the scoring rate per 100 balls bowled for every test series this century and I don’t think anyone else in the world has done that.” The numbers he quotes show the scoring rate unchanged in both England and Australia in 1955 as compared to 1902. The book also quotes Bradman refuting Rivett’s idea of moving from eight to six-ball overs, noting that the six-ball rate in a recent series was 1.898 balls per minute, while in the 1960-61 series it was 1.886, a difference of only three balls in a day. As to the question of limiting the run-up to enable more balls to be bowled, Bradman counters with “Besides you would make sure we never again saw the beauty of Wes Hall.”

The more major issues surrounding Bradman are well-known, such as the accusation that he was anti-Catholic. The author notes that these letters suggest otherwise; although at no point in the correspondence does he come out and say that. The author contends that with Rivett being a Mason it would surely at some time have come up in their quarter-century of back and forth.

Bodyline is touched on once or twice and one of the most enjoyable anecdotes is that, during the aforementioned 1953 Ashes series which Bradman followed and reported for the News, there was the delicious irony of Bradman beating seated next to Douglas Jardine in the press box at Headingley. No information is forthcoming on any discourse between the two, however. Bradman commented on one aspect of a piece written by Rivett in tribute to Vic Richardson, where he had written that Richardson and McCabe alone had ‘defied’ bodyline. Bradman felt this was a bit much given his own figures for the series and the fact that he, Bradman, had been the prime target. Another nice anecdote came as a result of the press roasting which Bobby Simpson had received when piling up 311 in thirteen hours in 1964, as Bradman recalled the monster innings by England at the Oval in 1938; Bradman recalled that Arthur Ward, who came in with England at 770/6 and departed at 876/7 having made 53, was congratulated by a member as he walked up the pavilion steps – “Thanks”, he replied, “I’m always at my best in a crisis.”

Speaking of England captains, though Bradman lauded Ted Dexter’s cavalier batsmanship he was not a great lover of his captaincy, claiming that he ‘imagined himself to be a god’ and decried his negative approach. Their cricket discussions were not always negative however – he urged Rohan to cheer up as they would both continue to love the game and get their share of pleasant surprises about it: ‘Like the boy who wrote me yesterday and said “I’m aged 11 and I’ve admired you ever since I was young”.’

As regards politics, there was quite a bit of discussion between the two on the proposed tour by South Africa in 1971-72, with Bradman pointing out that Australia was still trading and playing sports with other regimes where oppression was an issue, such as Russia and China, and that the South African Cricket Association was not responsible for Apartheid. Bradman was undecided as to the best course of action and particularly concerned as he was directly involved with the tour as chairman of the ACB. In any case, the offer to tour was withdrawn. That issue, and the management of the replacement tour by a Rest of the World XI, clearly took a lot out of Bradman though, as he noted ‘Have you ever stopped to think how much the hurly burly and turmoil of cricket have taken out of me in the last 40 years? All this has been fate, when a simple country lad wanted nothing more than to play cricket for fun and as a joy and recreation and loved the simple life in the country with birds and animals. What has happened to me has been by accident; thrust upon me if you like.’

The last statement suggests he was unsure that he was deserving of the esteem in which he was clearly held by an adoring nation. Another comment supports this – ‘If only I could speak like you,’ he told Rivett,‘with your flair & confidence. But somehow my inferiority complex reaches its zenith in speeches.’

No doubt his self esteem was not helped by his son John’s decision to change his name to Bradsen, though ironically this had opposite to the desired effect as the episode became the subject of a press fervour which upset Bradman Sr greatly – in what Bradman described as the cruellest story he had ever read, in the News, Murdoch’s paper previously edited by Rivett, Bradman notes ‘If ever a story was calculated to crucify and ridicule a decent person, this was it and it is something for which I shall never forgive them’. His son John’s ongoing depression and the way it impacted their relationship was clearly a great source of sadness to Bradman Sr – ‘This malaise is the supreme tragedy of my life for I seem so powerless to help’. That, coupled with his daughter Shirley’s learning disabilities and wife Jessie’s health issues led Rivett to note ‘I suppose the gods decided that the price of making you famous through at least three quarters of your own lifetime – an extraordinarily rare human condition – is the appalling catalogue of ills befalling Jessie, John and Shirley.’

In 1977, Bradman and his wife were shattered by the news of the sudden death of Rivett and sadly Jessie’s health issues meant that they could attend the funeral of his great friend.

The insight into Bradman’s thoughts and feelings passed on to us by the author in summarising these letters is in this writer’s opinion much more interesting than any biography, given Bradman’s lack of a public persona after his playing days. I heartily recommend the book.

Leave a comment