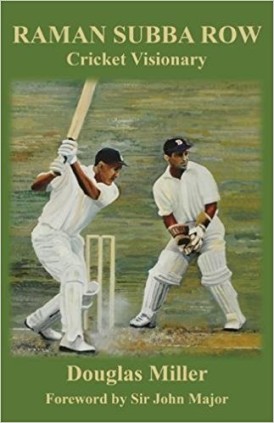

Raman Subba Row – Cricket Visionary

Martin Chandler |Published: 2017

Pages: 191

Author: Miller, Douglas

Publisher: Charlcombe Books

Rating: 3.5 stars

The years from1951 to 1961 were not the most profitable for batsmen in English cricket. There were plenty of good bowlers around and many playing surfaces were prepared with them in mind as much as for tall scoring. Career figures always have to be approached with some caution when making comparisons, even between contemporaries, but Raman Subba Row’s quality is perhaps best illustrated by the fact that his Test average from his thirteen appearances for England in that era is 46.85. That is a decent record for any period of the game’s history, and is a tick higher than that of Peter May, almost universally considered the finest English batsman of Subba Row’s generation.

Thirteen matches is not, of course, very many and the average does need to be approached with a degree of caution for that reason alone, but a closer look at the figures does not detract from the initial impression. Subba Row played just once against the weak New Zealand side of 1958, and had only a single opportunity against the poor Indian team of a year later. Of his three Test centuries two were recorded in the 1961 Ashes summer, and the other was an important innings in the Caribbean in 1959/60 when, at their fifth attempt, England finally won a series there.

On the subject of that first Test century Miller finds a marvellous quote from the long time cricket correspondent of the Times, John Woodcock, who described Subba Row’s batting as nudging and cutting and pushing and scotching, his shoulders hunched, his stance open…. a turn of phrase for the connoisseur, and an example of why somebody really should gather together an anthology of Woodcock’s best writing. For present purposes it illustrates, perhaps, part of the reason why Subba Row’s name does not resonate through the generations in the same way as that of some of his less statistically endowed contemporaries.

The Subba Row story begins in India where his father, who was to become a successful barrister, came from. Subba Row himself was born in Streatham in South London where he attended Whitgift School before going up to Cambridge to study law. His background was not so privileged that he could afford not to work, and he originally planned to leave the First Class game at the end of the 1954 season in order to, despite the law degree, pursue a career in accountancy. That Subba Row ever got to play for England at all therefore is thanks to Northamptonshire who, by virtue of being willing to allow him to combine cricket with accountancy training, persuaded him to stay in the game until the end of the 1961 season when, at 29 and leaving those centuries against Australia as a reminder of what might have been, he left cricket.

The chapters that deal with Subba Row’s playing career are comprehensive and thoroughly researched, albeit there is perhaps an over reliance on summarising match details. As the quote from Woodcock demonstrates there is not too much excitement in Subba Row’s cricket, but the chapter on his tour with the Commonwealth XI that visited the sub-continent in 1953/54 is an interesting one. There are digressions on the lives of the Indian Test cricketers Madhav Apte and CD Gopinath. Both are enjoyable and illuminating. The constant tension in the game’s corridors of power over the amateur/professional distinction is a thread that runs throughout Subba Row’s time as a player, and one of the book’s strengths is as lucid an explanation of that complicated subject as I have read anywhere.

His playing days done Subba Row went into marketing, eventually setting up his own business. He also continued to play the game at club level and, more importantly for Miller’s purposes, was heavily involved in the administration of the game, initially at Surrey, his first county. In time he moved on to the MCC/TCCB and, through the 1990s, back onto the international stage as he undertook the role of ICC Match Referee in 41 Tests and 119 ODIs.

One of the features of Miller’s writing (he has written six previous biographical books on the game*) is that his subjects all co-operate fully with him and spend many hours in his company. There is therefore nothing of the inevitable detachment that creeps into a biographical work on a long deceased subject. As a result much of the man himself comes across in the pages of Raman Subba Row – Cricket Visionary. It is clear one of his great skills was diplomacy, and the avoidance of controversy and confrontation. There is therefore nothing within the book that will cause offence to anyone, but plenty of insights into many areas of the modern game. The chapter that deals with England’s controversial tour of Pakistan in 1988, often remembered Shakoor Rana’s notorious spat with Mike Gatting, is probably the highlight.

For all Douglas Miller’s skills as a biographer his subject’s equable personality means that he hasn’t quite managed to lift this life of Raman Subba Row into the ‘indispensable’ category of cricket writing, but he has told an interesting story with his usual skill. The result, for those interested in Subba Row and his life and times, is an entirely satisfactory book. The point should also be made that the end product, inevitably given Stephen Chalke’s involvement, is an attractively printed hard back, very well illustrated** with a statistical appendix as well as an index. Finally, there is an excellent foreword from Sir John Major, a man who I may not always agree with on some subjects, but who is someone whose thoughts on cricketing matters are always worth reading.

*The six are, with links to our reviews where appropriate,

On Charles Palmer – More Than Just A Gentleman (Fairfield Books, 2005)

On Allan Watkins – Allan Watkins: A True All-Rounder (ACS, 2007)

**Even if Raman Subba Row’s life doesn’t fill you with anticipation the book is worth buying for the photograph that appears on page 83 alone.

Leave a comment