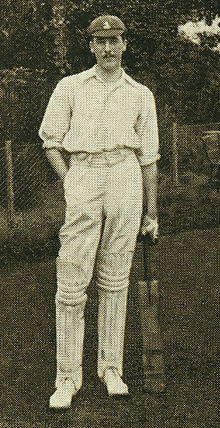

Frank Woolley

Martin Chandler |

Cricket betting tips are available at https://oddsdigger.com/tips/cricket

Half a century ago the reputation of Frank Woolley was immense. Back then records of accumulation were important, and 58,969 career runs was the second biggest total there was. Woolley had other strings to his bow as well. He had held more catches than anyone, 1,018, and just to complete the all-round picture, took 2,066 wickets despite knee problems reducing his effectiveness as a bowler for the latter fifteen seasons of his career, so much so that for a number of those summers he was no more than an occasional bowler.

In the 21st century the old records are of limited relevance. It is more than 20 years since a bowler joined the 1,500 club, and even then Eddie Hemmings owed much to having a career that spanned thirty summers. There were 16 England caps for Hemmings along the way, but no one would suggest that it was ability rather than longevity that sees him as the 80th highest First Class wicket taker of all time. Amongst batsmen the position is slightly different, Graham Gooch just sneaking into the top ten and Graeme Hick five places behind, but it seems unlikely that anyone else is going to get remotely close. Kumar Sangakkara, who seems to have been scoring runs in huge quantities for years and years, has only just passed 20,000 in First Class cricket, and even in all formats has not yet reached 50,000.

Where statistics are concerned eyes now go straight to averages. For Woolley that means a career mark of only just over 40 with the bat. His bowling average is a rather more impressive 19.87, but then there is his Test record. Woolley came into the England side for the final Test against Australia in 1909. It was more than 17 years before he was left out of an England side and by the time he played his last Test, ending as he begun against Australia at the Oval, a quarter of a century had gone by. His 64 caps were a record at the time, but his averages weren’t. With the bat he averaged a relatively modest 36.07 and with the ball 33.91. Even taking into account the years when he seldom bowled a tally of 83 wickets is nothing too special either.

But there is no doubt that for my father’s generation Woolley’s name was one to be revered, his reputation fuelled by what they had been told by their fathers, who had of course seem him play. There is newsreel footage of Woolley, but as is so often the case it is of limited value in helping to, a century on, understand what all the fuss is about. In the absence of good quality film of Woolley we have to rely on the impressions of others, although even the great scribes of the era had some difficulty.

‘Crusoe’ Robertson-Glasgow was one of the best of his time, and he summed up the problem with describing Woolley thus; Frank Woolley was easy to watch, difficult to bowl to, and impossible to write about. When you bowled to him there weren’t enough fielders; when you wrote about him there weren’t enough words.

Neville Cardus was never lost for words, although even he struggled with Woolley, one of his great favourites. At his peak he wrote cricket belongs to summer every time that Woolley bats an innings. His cricket is compounded of soft airs and fresh flavours. The bloom of the year is on it, making for sweetness. In the 1960s a much older Cardus reflected that, perhaps, he had been just a little too lyrical with those words, although his older self had not changed much, his description then being; his batting was somehow luminous, and part of the Kentish scene. His bat surely sent out sounds never heard from any other cricketer’s bat, muted music of the game.

Woolley made his First Class debut in 1906, in front of Cardus at Old Trafford. The 19 year old had a torrid time initially. In the manner of the times slow left armer Woolley opened the bowling with Kent’s fastest bowler, Arthur Fielder. It could have been worse, as he did eventually take the wicket of the Lancashire skipper, AH Hornby, but he went for more than a hundred as Lancashire spent most of the first day building up an impregnable 531. JT Tyldesley contributed 295 of them. Woolley, destined to become the most prolific catcher in the game, put ‘John Tommy’ down twice. In Kent’s reply he started with a duck. Back to the hop fields, was Cardus’ verdict. But then in the second innings, batting at eight, Woolley scored what Cardus would describe as a dazzling 64, and despite all the subsequent superlatives he later wrote that Woolley never improved on the ease and grace of that baptismal innings.

Over the course of his career there were to be 88 ducks for Woolley, or 6% of his completed innings. In Tests the figures were 12 and 13%. The reason was, and of course one that made him so popular with the crowds, that he never allowed himself to be tied down, and always went for his shots. He was well over six feet in height, slim, and had a long reach that he made full use of. He was also happy to hit the ball in the air, always by its nature a risky manoeuvre, and if the first ball he faced was in the slot it would usually go straight back over the bowlers head.

His approach never changed however long Woolley was at the crease. He went to his century no less than 145 times and, interestingly, also had 35 scores in the nineties. The reason was not nerves, but the fact that he didn’t stop playing his natural game whatever personal milestone he might be approaching. That said one curious aspect of the nineties is that there were none at all in the last six summers of Woolley’s career, during which time he successfully negotiated them on 26 occasions. Perhaps towards the end, once he had celebrated his 45th birthday, he was just a little more cautious.

As a bowler Woolley clearly learned much from his mentor, Colin ‘Charlie’ Blythe. His action was said to be similar and he was assisted by his height in extracting at least some bounce from the most placid of pitches. Woolley was also a big spinner of the ball, and in helpful conditions could be lethal. In 1913 Kent played Warwickshire at Tonbridge and conceded a first innings deficit of 130. Rain then turned the pitch into a treacherous one and in ten overs and 45 minutes the master Blythe and his pupil Woolley dismissed the visitors for a mere 16, taking five wickets each. The wicket hadn’t, of course, improved at all and no one expected Kent to make the 147 they needed. That they did for the loss of just four wickets was due to a characteristically aggressive unbeaten 76 from Woolley.

Kent won the County Championship in 1906, and became a power in the land. They regained the title three years later, by which time Woolley was considered a genuine all-rounder. In 1909 he forced his way into the England side for the final Test, one of his eye catching performances being his sharing a partnership of 235 with Fielder against Worcestershire at Stourbridge for the tenth wicket, still an English record more than a century later. In the event he achieved little for England on debut, but as noted it was the first of 52 consecutive appearances.

England toured South Africa that winter and Woolley did reasonably well without making any outstanding contributions to England’s victory. The next home season however saw him make great strides, doing the double for the first time and helping Kent to another title. His form fell off a little the following summer, but he did enough to get in the party for the 1911/12 Ashes. England won the series 4-1, Sydney Barnes and Frank Foster bowling wonderfully well after defeat in the first Test. For Woolley there was a minor role, until the final Test at Sydney where he made a match-winning contribution with the first of his two Test centuries against Australia. He came in at 125-5 after England won the toss and chose to bat and was still there, unbeaten on 133, when the tenth wicket fell 199 runs later.

In the Triangular Tournament that followed in the English summer of 1912 there was another dominant performance against Australia. In a disappointingly wet summer the first two of the three Tests against Australia were drawn. In the third he contributed an important 62 to England’s first innings 245 and then took five wickets in each Australian innings to help England to win by 244 runs. His match haul of 10-49 was the best of his career.

In 1913 Kent won their fourth Championship title, and their last until the 1970s. Woolley was described by Wisden as being; out by himself as being the all-round man of the team. It was no surprise when he got the nod to travel to South Africa again, but although he played in all five Tests he never really fired, the matting wickets suiting neither his batting nor his bowling. His powers in England however continued to grow in the last pre war summer when he headed Kent’s batting averages and was second only to Blythe in the bowling. He also secured the rare double of 2,000 runs and 100 wickets in the season, the first of a record four occasions on which he was to achieve that feat.

The Great War was meant to be all over by Christmas, so despite being extremely surprised the newly married Woolley was not unduly troubled when, in attempting to follow his three elder brothers into the Kent Fortress Engineers, a volunteer Territorial Army unit, he was failed on medical grounds. The examiner found dental problems and, particularly remarkably, defective eyesight.

Unable to join up Woolley worked for his father. Woolley senior had owned one of the very first car repair garages in Kent, but had given his business over to the manufacture of munitions for the duration. Once it became clear that the war was not going to be over in a hurry however Woolley decided to try and join up again. This time he passed the medical without difficulty and joined the Royal Naval Air Service.

Initially, after completing his training, Woolley was the coxswain of a rescue launch tasked with rescuing pilots whose planes came down in the sea. In truth it was a depressing duty as the pilots were seldom picked up alive, and there was much cutting of corpses free from wreckage. Woolley was probably relieved when he was posted to North Queensferry on the Firth of Forth, a long way from enemy action, and that is where he saw out the hostilities.

It would be interesting to know how many families, like the Woolleys, contributed four sons to the Great War with all surviving. It cannot have been many. In 1919 Woolley and his less famous older brother Claude rejoined their counties. Claude, universally known as ‘Dick’, bore a striking resemblance to Frank and indeed was on the Kent staff with him between 1906 and 1908 without ever making the first team. After one appearance for Gloucestershire he joined Northamptonshire in 1911 and played for that county until 1931. As a cricketer he was essentially a right handed version of Frank, albeit without quite the same talent. He has a relatively modest career record, but was an important player in a weak side throughout the 1920s.

In a somewhat reduced first post war season in 1919 Woolley still managed to do the double, and the following year he had his best ever season with the ball, 185 wickets, before travelling to Australia once again. Johnny Douglas’ side lost 5-0 and with the exception of Jack Hobbs, who averaged 50, none of the Englishmen lived up to their reputations. Woolley did make four half centuries, but didn’t go on and averaged only 28.50. His nine wickets were expensive, costing well over fifty runs each.

The return series in 1921 threatened at one stage to be even worse. With Hobbs injured a makeshift England side were dismissed in the first Test for 112 and 147 and beaten by ten wickets. With 20 and 34 Woolley was the second top scorer in both innings. Writing fifty years after the event Ralph Barker wrote; only Woolley, though frustratingly free from free scoring, gave the effect of competence, reserves of technique and hints of mastery.

A much changed England lost the second Test as well, an eight wicket margin not sounding very much better. But the match is notable as being Woolley’s finest performance for his country. In the first innings he scored 95 out of 187, perishing selflessly in trying desperately to score runs quickly as all collapsed around him. Finally he took one liberty too many with the leg spin of Arthur Mailey and, in attempting to hit him out of the ground, was stumped by yards.

Exactly how Woolley was dismissed in the second innings, on 93, is not entirely clear, and makes a man yearn for the re-discovery of some long lost piece of Pathé celluloid. That Mailey produced a long hop is not in dispute, nor that Woolley struck the ball in the meat of the bat. No source disputes that Hunter ‘Stork’ Hendry took a magnificent catch. It is where and how that is not clear. According to Ian Peebles, Woolley’s biographer, Hendry was at mid wicket and leapt at the ball, succeeding only in pushing it up in the air. He then fell on his back before, luck going his way, the ball dropped into his midriff where he caught it. Barker on the other hand has Hendry at short leg, and taking a brilliant catch, an account that Wisden corroborates. The Cricketer is non-committal about where Hendry was or whether he fell over, but describes three or four attempts.

It might have been expected that Woolley himself would have the best recollection, and indeed he dwells at some length in his 1936 autobiography on the two innings he describes as, the two greatest I ever played, but whilst he describes the first innings stumping in some detail he sheds no light on Hendry’s catch.

There were to be three more occasions when Woolley did get past the nineties for England. Once was in South Africa in 1922/23, an isolated high point in another struggle on the mat. The next came in a home series against the same opposition in 1924, a series in which he averaged 83. He then had his last tour of Australia with Arthur Gilligan’s side in 1924/25. England lost 4-1, although with the emergence of a new generation, men like Maurice Tate and Herbert Sutcliffe, it was clear they were going in the right direction. Woolley’s form was patchy, but there was a fine century at Sydney.

Gilligan over-bowled Woolley on the trip, and an old knee injury was aggravated and became a permanent handicap. No longer could Woolley bowl with his old action and, limited to an approach of a couple of paces, his days as a true all-rounder were over.

Woolley retained his England place throughout the 1926 Ashes, his second experience of regaining the Urn. After that his England appearances became less frequent, although in 1929 he came back for the last three Tests against South Africa and averaged 127. Those performances made sure he figured in his seventh series against Australia in 1930, although he was dropped after the second Test. At 43 most expected that to be that, but after scoring heavily throughout 1934 the selectors persuaded Woolley, against his better judgment, to play in the last Test of that Ashes series. Innings of 4 and 0 were testament to the fact that Woolley was right, and his nightmare became worse when he opted to take over the gauntlets in the Australian second innings when Les Ames was injured. The 47 year old had not, despite his prowess at slip, ever kept wicket before and he conceded as many as 37 byes, many of them from the bowling of the decidedly quick but wayward Northamptonshire left arm fast bowler EW ‘Nobby’ Clark.

For Kent Woolley carried on playing for another four summers, until the end of the 1938 season. Even at the age of 51, he was still good enough to score more than 1,500 runs during that swansong. Indeed in the last couple of summers of his career he even took a few wickets, including eleven in the match against Leicestershire at Oakham less than a month before his final appearance.

His First Class career over Woolley became a coach at King’s School, Canterbury. When war broke out in 1939 the Woolley family contributed fully. Woolley himself joined the Home Guard, his two daughters joined the women’s services and his son was a radio operator in the Merchant Navy. Sadly the family were not to be as fortunate as they had been in the previous conflict. Richard Woolley worked the lifeblood of the nation, the Arctic convoys, and in November 1940 his ship was sunk with the loss of all hands. A few months later, fortunately whilst the property was empty, a stray German bomb dropped on the Woolley home, flattening it and destroying almost all of their possessions.

In 1946 Woolley, who had not played serious cricket since retiring and was by then 58, turned out in a famous charity match at the Oval between Surrey and an Old England XI. After a scratchy start, and a reluctance on the part of the Surrey side to appeal for LBWs, Woolley and Patsy Hendren, one year his junior, rolled back the years to the delight of the packed house. Woolley was finally dismissed for 61, Hendren went on to 94 and Old England secured an honourable draw.

Woolley was destined to enjoy a long retirement. He spent one summer organising cricket matches and doing some coaching at a Butlin’s holiday camp in Clacton-on-Sea, but he did not repeat the experiment. He was a regular attender at Test matches in England, Jack Hobbs, Sydney Barnes, Wilfred Rhodes and Herbert Strudwick all being regular companions. In 1964 he suffered a great setback when his wife of fifty years died and Woolley finally left Kent to live with his younger daughter in Hertfordshire.

In 1971, after taking what proved to be his last trip to Australia to watch two of the Tests as Ray Illingworth’s England regained the Ashes, Woolley married again. His second wife was Martha, the widow of a US serviceman, and the couple moved to Canada. Woolley still followed the game however, the intensity of his interest being such that in 1975, at the age of 88, he felt the need to write to The Cricketer, expressing his appreciation of their coverage of the game now that he was living so far away from England, and at the same time expressing his disappointment over England’s humiliation the previous winter by Dennis Lillee and Jeff Thomson. He clearly watched the series carefully as he commented on his surprise in the Adelaide Test at, on a sticky wicket, off spinner Fred Titmus being taken off after just a single over and not being bowled again.

In his 1975 letter Woolley talked of visiting England later that year. A bout of pneumonia prevented that but he was well enough to travel in 1976 and visited England then. A long interview with David Frith, then editor of the magazine, was serialised in three autumn issues. It is difficult to imagine that Woolley would not have, if humanly possible, have accepted the invitation of the Melbourne Cricket Club to attend the centenary Test celebrations in 1977 but unfortunately his health would not permit it. Frank Woolley died at the age of 91 on 18 October 1978, in a nursing home in Nova Scotia.

Woolley was an immensely popular man and a month after his death his family and the great and the good of Kentish and England cricket gathered at Canterbury Cathedral for a memorial service. That Woolley was, despite his average, a great batsman is borne out by the views of no less a judge than Sir Donald Bradman. Though more than twenty years younger than Woolley the longevity of the latter’s career meant that they did face each other. Bradman was particularly impressed by the 42 year old Woolley when, in 1929, he scored 219 against Bradman’s New South Wales. Forty years later he wrote it remains one of the most majestic and classical innings I have seen, with every stroke in the book played with supreme ease.

Cricket Live odds and fixtures are available at https://oddsdigger.com/

As far as Woolley as a man is concerned the last word goes to former England Captain Bob Wyatt, who put on 245 with Woolley against South Africa at Old Trafford in 1929; I never heard anyone say they didn’t like Frank Woolley. He was popular wherever he went, mainly because he was such an unselfish cricketer. He would go in anywhere. If his captain wanted quick runs in the most difficult circumstances he would open the innings without any hesitation. He never thought of himself, or what effect failure might have on his personal record, because figures meant nothing to him. As far as his place in history is concerned I shall always think of Frank Woolley as the finest left-handed batsmen I have ever seen.

Leave a comment