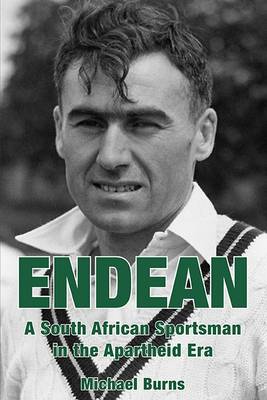

Endean

Martin Chandler |Published: 2017

Pages: 144

Author: Burns, Michael

Publisher: Nightwatchman Books

Rating: 4 stars

Russell Endean played 28 Tests for South Africa in the 1950s. He was a top order batsman who ended up with an average of 33.95. He didn’t bowl, but did have a second string to his bow. He was a more than capable wicketkeeper, although he generally ceded the gauntlets to John Waite. An exceptional fieldsman, both close to the wicket and in the outfield, the book begins with a brief account of a wonderful catch Endean once took to dismiss Keith Miller.

At first blush it is perhaps surprising that a biography of a man who had a relatively modest career so many years ago has appeared, particularly given that most of his cricket career was played out so far away. A quick scrape at the surface however and all becomes clear. Endean left South Africa in 1961 and spent the rest of his life in Surrey. There he played club cricket with film maker Michael Burns who got to know him well and, thankfully for the rest of us, has now had the time to write his old friend’s story.

We have reviewed a book from Burns before, his very readable story of Jack Crawford. Whilst Burns might have spent his working life in film he is a skilled wordsmith as well and there is something about his writing that brings what he is describing to life. It helps to have some decent material of course, and despite his not particularly exciting looking statistics Endean certainly had his moments. Two of his three Test centuries, the first in Australia in 1952/53, and the third in England in 1955 proved pivotal in important South African victories. For collectors of cricketing trivia he also ranks highly in stories of unusual dismissals. He played, whilst keeping wicket, a crucial role in Len Hutton’s dismissal for obstructing the field in the final Test in 1951 (still the only instance of that occurring in Tests). Six years later, again against England, he was himself the first batsman to be dismissed handled ball in a Test. In that respect nine others have joined him in the record book since.

There are some fascinating insights in Endean, and that is why there is never any danger of, as sometimes happens, the chronological trip through its subject’s cricket career becoming pedestrian. A good example relates to Denis Compton’s second innings dismissal in the first Test of the 1956/57 series in South Africa. The scorecard tells you Compton was caught and bowled by Hugh Tayfield for 32. Compton wasn’t sure the ball had carried, and asked Tayfield whether he had made the catch. He walked as soon as the bowler confirmed that he had.

According to Burns the ball actually bounced a couple of feet in front of Tayfield, and non-striker Doug Insole suggested Compton ask the umpire, advice ignored even when it was repeated by Endean as Compton walked past him on his way back to the pavilion. The reader must assume from what Burns writes that Endean must at some point have described Tayfield’s actions to him as cheating rather than merely mistaken. The reports in Wisden and The Cricketer carry no suggestion of controversy. As for the tour accounts there are four, by English writers Jim Swanton and Alan Ross, South African journalist Charles Fortune and one member of the South African team, Roy McLean. The sum total of their accounts is that there was doubt, but that on appeal from South African skipper Clive Van Ryneveld the catch was confirmed. Only Ross demonstrated any hint of real concern. Compton failed to make any mention of the incident in his end of career autobiography, so perhaps unsurprisingly two of Compo’s biographers, Peter West and Tim Heald, add little.

Van Ryneveld’s autobiography appeared a few years ago, and he admitted to having doubts about the catch, but interestingly makes no mention of appealing – I wonder where that idea came from? Burns also spoke to Van Ryneveld, and to Insole, and read the latter’s account from his 1960 autobiography. Clearly it was an incident he also discussed at some point with Endean. It has therefore taken 60 years to get a reliable account, a timely reminder of that old truism, counselling against unconditionally believing what you read.

In England in 1955 Endean met his future wife, Muriel. She followed him back to South Africa where the couple married before moving to the UK with, by then, a family of four (it later became five). The rest of Endean’s life is not dealt with at great length, but is given rather more attention than is usual in a sportsman’s biography. The story is, in many ways, an unremarkable one but is thought provoking nonetheless. That in part is because, like the rest of Endean, it is so well written, but also because the family faced issues which, sadly, more and more of us are going to have to deal with in the future.

As far as publication is concerned the book bears Burns’ own imprint, although that is stated to be ‘in association’ with Stephen Chalke’s Fairfield Books. The book is well indexed, carries the statistics that are needed and is exceptionally well illustrated, designed and produced. In that sense it has the mark of Mr Chalke all over it – Endean is highly recommended.

Leave a comment