The Tale of Two Cornishmen

Martin Chandler |

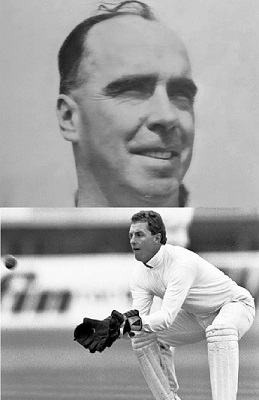

Population figures are not generally a source of great interest to me, but two that have always stuck in my mind concern the English county of Cornwall and the Caribbean nation of Barbados. In broad terms there are around twice as many Cornish folk as Bajans. Cricket is the summer game of both. When West Indies played their first Tests, back in 1928, there were three Bajans in the side, and in the intervening years more than 80 more have been capped. England’s first Test was back in 1877, and there were no Cornishmen in the side. It took 71 years for Jack Crapp, born in St Columb Major, to be selected for the first of his seven Tests, and another 38 for Jack Richards from Penzance to make the first of his eight appearances. They are the only two, out of 670 men to have won England caps, to hail from our westernmost county.

Both Cornishmen were capable batsmen, and both were very capable catchers, Crapp at slip and Richards behind the stumps. As men however they were very different. Crapp was a popular and easy going character, whereas Richards had a much more fiery temperament. After Crapp retired he remained in the game as a popular umpire. When Richards was to all intents and purpose sacked by his county, Surrey, he turned his back on English cricket, and has never returned.

Despite being born in Cornwall Crapp did not spend a great deal of his childhood in the county. His father was killed in France in 1917. Crapp’s mother must have been a remarkable lady because, whilst still grieving, she gathered up Crapp and his sister and walked the 150 or so miles to Bristol in order to find work. As he grew up young Crapp demonstrated his cricketing talent and was also a useful footballer, his powerful build making him an ideal centre forward. His key year was 1935 when, as a 22 year old, he decided to move to a higher standard of cricket and joined Stapleton, one of the leading Bristol clubs.

Initially at Stapleton Crapp was in the third team, but it was just two weeks before he was in the first eleven. The writing was on the wall when, in only his third start for the club he led his side in a successful pursuit of 218 in two hours with an unbeaten 131 from number five. To complete a meteoric rise by the start of the following summer Crapp was on the Gloucestershire staff, and making his first team debut.

The role Crapp fulfilled for Gloucestershire was as a top order batsman. He was by no stretch of the imagination an all-rounder, and in his entire career took just six wickets. According to those sources that make reference to his bowling on those occasions when he did turn his arm over Crapp bowled a bit of left arm spin. Half of his First Class wickets came in a game against Leicestershire in his second season, 1937. In those days Gloucestershire were skippered by Beverley Lyon, who had a well earned reputation for being unconventional. In more than a quarter of a century Lyon himself only took 52 wickets, but he chose that day to open the bowling with himself and Crapp and he took three wickets as well.

With the bat despite his brisk batting in club cricket, Crapp’s reputation was as an accumulator. Given that he came into a county side that contained the imperious Walter Hammond, and another attacking England batsman in Charles Barnett, consistency and solidity suited the county well. Perhaps the fairest summary appeared in an appreciation written for his benefit season in 1951; Possessed of a cast iron defence, Crapp is usually inclined to play a careful game, but when the mood is on him he can bat with delightful freedom.

Making his First Class bow in the county’s first match of that 1936 season Crapp top scored in Gloucestershire’s first innings against Oxford University with 60. These were the days when the Universities were rather stronger than they are today and, with Hammond absent, they won the match. Crapp cemented his place at that first available opportunity and made his 1,000 runs for the summer, something that with one exception he achieved ever year between then and his last, 1956.

In the last couple of years before the Second World War began Crapp was talked of as a future England player, but he was 34 when the county game resumed after the war. He had joined the RAF early on. In 1942 The Cricketer reported that he had spent many weeks on his back as a result of a footballing accident, but was not specific about the type of injury. Whatever it was he got over it well enough to score prodigiously in club cricket in 1943, and to take his place in the Gloucestershire eleven at the start of 1946.

By 1947 Hammond had retired. Crapp had spent a great deal of time at the wicket with the great man, but like almost everyone else found him difficult to get on with. He later said that only once did Hammond ever give him any advice, that being in a match against Warwickshire when he was told that Eric Hollies was not turning his leg break. That of course says infinitely more about Hammond than it does about Crapp. In the glorious summer that followed Crapp just missed 2,000 runs for the season. It was not enough to earn him a Test cap against South Africa but when his form continued into the following summer the selectors looked to him as a means of blunting the threat posed by Ray Lindwall, Keith Miller and the rest of Bradman’s Invincibles.

By way of warming up for his Test debut Crapp scored an unbeaten 100 and 34 in Gloucestershire’s defeat by Bradman’s side by the small matter of an innings and 363. Lindwall was playing but Miller was not, but the ‘Golden Nugget’ is supposed to have said to Crapp after the game Well done Jack, but watch your head in the Test. The long awaited debut came in the third Test at Old Trafford, a game in which England held the upper hand throughout and might, had the fourth day not been washed out and the fifth curtailed as well, have even won.

England won the toss and skipper Yardley chose to bat. When Crapp came to the wicket the score was 28-2 and Denis Compton was back in the pavilion after top edging an attempted hook on to his forehead. John Arlott described Crapp’s demeanour as being as placid as a man starting a day’s work in the fields. He got off the mark first ball and with Bill Edrich took England to lunch. Straight after the interval he straight drove off spinner Ian Johnson back over his head for six. He must have been bitterly disappointed to be lbw to Lindwall on 37. There was no issue with the decision itself, but Crapp had shouldered arms to a delivery that, according to Arlott, curved in like a boomerang more sharply than I have ever seen a ball swing before from a bowler of such pace. Crapp was unbeaten on 19 when Yardley declared England’s second innings.

Retaining his place for the fourth Test Crapp made 5 and 18, although in mitigation he was dismissed in the second innings when following team orders and looking for quick runs. In the fifth Test he was dismissed for 0 and 9. Before he was dismissed in the first innings he was guilty of not, as he had been advised to do in the county game by Miller, watching his head. After being struck full on by a bouncer Crapp stayed on his feet and, after a short delay, resumed his innings. He might have been wiser to retire hurt.

Despite those low scores Crapp was still taken to South Africa the following winter. He missed selection for the first Test, the tour management preferring the stroke play of Reg Simpson. But Simpson failed twice in England’s narrow victory and Crapp’s defensive credentials were preferred for the rest of the series. Crapp did not do at all badly and contributed a half century to each of the second, third and fourth Tests. In a desperate run chase in the final Test Crapp was held back whilst supposedly more free scoring batsmen were promoted above him. Amidst the chaos though he was needed at the end, and scored 26 in 21 minutes to carry England to victory just as time was about defeat them.

Although he was 37 by the time the 1949 season began Crapp must have expected to get the opportunity to add to his seven caps but despite, for the only time in his career, topping 2,000 runs he was not invited to play against New Zealand. There was no thought of retirement for discarded Test players in those days and Crapp went back to Gloucester and continued to bat consistently for another seven summers. Only once, in 1954, did he fail to reach his 1,000 for the season. That was the second of his two seasons as captain. He was the first Gloucestershire professional to do the job but, as a man with a fairly reserved nature, he derived no great pleasure from it. His performances that summer might also have been affected by the illness he contracted whilst with a Commonwealth XI that toured India in 1953/54 and which restricted him to just two appearances at the start of the tour before forcing him to return home.

Back in the ranks under the leadership of his old friend and contemporary George Emmett Crapp was much more successful in 1955, and still an effective performer in 1956, the summer that proved to be his last. In 1957 the 44 year old joined the First Class umpires list and remained on it until the end of the 1978 season when ill health forced his retirement. In 1964 and 1965 he was on the Test panel and stood in four Tests, including the Oval Test in the 1964 Ashes series when Fred Trueman took his 300th Test wicket. In 1966 the number of umpires on the Test panel was reduced, hence Crapp making way. A lifelong bachelor Crapp lived in a small council flat in the Knowle area of Bristol. He was 68 when he died in 1981.

Jack Richards was born in Penzance in 1958. In 1975 he wrote a letter to the former England wicketkeeper Arthur McIntyre, then coach at the Oval, asking for a trial. McIntyre was struck by the keenness of a young man who was prepared to travel so far and responded positively. He liked what he saw and persuaded Richards to leave school the following year and move to London. The young man’s progress was such that he made his First Class debut in 1976, and was a regular the following year. Only twice was he umpired by Crapp, two rain ruined matches in which the young Cornishman spent just 4.3 overs keeping wicket, so old Jack never got a good luck at the man who was to emulate him in a few years time

International recognition first came Richards’ way in 1981/82 when he toured India as the reserve ‘keeper to veteran Bob Taylor. In two ODIs on the sub-continent and one more against Sri Lanka the following summer he achieved little and was discarded. He had to watch Paul Downton, David Bairstow and Bruce French all get their turn before his second call up came against New Zealand in 1986, one of England’s grimmest summers. He was barely more successful in two ODIs that time round but his form for Surrey meant that he did enough to be selected as French’s understudy for Mike Gatting’s Ashes side of 1986/87, the one that left these shores with journalist Martin Johnson’s famous quip ringing in their ears, that the team had only three problems, inabilities to bat, bowl or field.

In the run up to the first Test England’s batting indicated that Johnson’s call was at least partially correct, so the decision was made to prefer Richards to French. He was castled for a duck by Chris Matthews from the fourth ball he faced in the England first innings and didn’t get to the crease in the second, but his competent display behind the stumps in England’s unexpected victory kept him in the side for the second Test at the WACA. Gatting won the toss and chose to bat. England’s openers, Chris Broad and Bill Athey, put on 223 but by the time Richards came in to join David Gower the score was a less impressive 339-5. The pair put on 207, Richards outscoring his illustrious partner comfortably. Eventually he was eighth out for 133.

The Perth game was drawn, as was the third Test at Adelaide. England won again in the fourth Test at the MCG to take an unassailable 2-0 lead and this time Richards played an important role with the gloves. After putting Australia in England, courtesy of five wickets from Gladstone Small and Ian Botham’s final five-fer, dismissed Australia for 141. There were two routine catches for Richards as well as another high above his head, one diving one handed in front of slip and a fifth following a full length dive as he ran hard towards a top edge from Craig McDermott that flew to backward square leg.

Australia had a consolation victory in the final Test, but with four catches and innings of 46 and 38 Richards was certainly not to blame. The series did not however prove to be a launchpad for a long career. By the time the Pakistan series began in the English summer of 1987 French was back behind the stumps, and Richards played just once in the series when chicken pox laid his rival low. He scored 6 and 2 in England’s innings defeat. His only other Tests were the last two of England’s woeful series against West Indies in 1988. His contributions with the bat were 2, 8, 0 and 3. Richards’ international career was over as indeed, at the age of just 30, was his county career. That was despite his leading the Surrey batting averages for the 1988 summer, when he also enjoyed a successful benefit.

What happened? In Richards’ own words he was well aware I am not the most popular guy on the county circuit. A lot of fellows don’t care for me. Why should they? I am aggressive out there, and aggressive for my team. Alec Stewart, whose presence Richards understandably saw as a potential threat to his own position, wasn’t a great fan describing him in his autobiography as a hard, difficult individual. He also wrote that Jack Richards liked to have something to moan about. Even if it was irrelevant. He was not a man for the team ethic.

The 1988 problem was that Ian Greig had become Surrey captain and did his best to rid the county of what he saw as its more disruptive elements, Richards and maverick batsman David Smith foremost amongst them. The decision to release Richards from the final year of his contract was taken in the September, but not made public until the New Year in order to avoid any disruptions to Richards’ benefit functions. The total proceeds were almost £110,000.

By then Richards must have been somewhat disenchanted with life as a professional cricketer, otherwise surely he would have been able to find another county. In the event he chose to move to the Netherlands where he became involved in a successful shipping company. He now lives in Belgium and is a director of an international recruitment and crewing agency. He seems not to have maintained any links with the game in England save for occasional coaching sessions in his native Cornwall, although he is not entirely lost to the game as he is currently the coach to the Belgian national side and President of Antwerp Cricket Club.

Despite his criticisms of his one time rival Stewart also wrote of Richards; He was too talented to leave English cricket as early as he did, before adding, his harshness did me a favour without his realising it. It helped with the toughening up processes necessary to survive in professional sport. No doubt that mental strength helped Richards in business, and assists in explaining the success he has made of his second career.

When will Cornwall produce another Test cricketer? There are none on the horizon that I am aware of, the closest being Somerset’s Overton twins who hail from Barnstaple in Devon. There has been talk of late of the Devonians and Cornish pooling their resources to produce a side to join a new third tier of the county game – perhaps we will have to wait for that project to come to fruition before we see a third Cornish Test cricketer.

Leave a comment