A Notable Centenary

Martin Chandler |

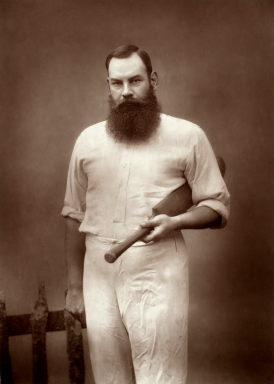

Almost 100 years after his death William Gilbert Grace remains one of the most instantly recognisable figures who ever set foot on a cricket field. But the aura around his achievements has been tarnished as the statsguru generation have grown up. These numbercrunchers, who know the average of everything and the quality of nothing, point to a Test match batting average of 32.29 over a 22 match career and, for a man who was supposed to be a great all-rounder, just nine wickets at 26.22.

The reality is however that during his time in the game Grace bestrode cricket like a Colussus and in the view of many remains the only realistic challenger to Donald Bradman as the greatest to have played the game.

Statistics can be used support Grace as much as a narrow band of them can be used to attempt to undermine his status, but it should not be forgotten that part of the reason for his becoming the legend that he is arises out of his altering the art of batsmanship irrevocably, as well as being one of its greatest exponents.

Grace was born in 1848 and was just 16 when he made his First Class debut for the Gentleman of the South against the Players of the South at the Oval. A look at the teams reveals no famous names amongst Grace’s teammates, two of the seven strong Walker brotherhood of Southgate being the most familiar. The Players incuded in their number two of the Lillywhite brethren, John and James, the latter going on a decade later (although he didn’t know it at the time) to be England’s captain in the first ever Test match. Also in the Players’ line up was Edgar Willsher, a left arm fast bowler best known for being the man who effectively forced the change in the law which, from the previous season, had made overarm bowling legal.

The match was an unexpectedly straightforward victory for the Gentlemen, who won by an innings and 58 runs. Winning the toss and batting first their own total was a modest 233, thanks largely to 91 from Isaac Walker. Grace, batting at first drop, had the worst start a batsman can have to his career, and did not trouble the scorers. He made up for it with the ball however. He and Isaac Walker bowled right through both Players’ innings. In the first he took 5-44 and the second 8-40 as the paid men were bundled out with a day to spare.

It didn’t however take long for Grace’s batting to take off, and the following season, when he was only just 18, he played for a powerful England side, again at the Oval, against Surrey and recorded an unbeaten 224, the first double century that had been scored in a First Class match since the days before even round arm bowling was legal.

It was in batting where Grace revolutionised the game. Until he arrived there were, essentially, four different types of batsman. Firstly there was the “back player” like Robert Carpenter who, in the mid 19th century, was an outstanding right handed batsman who was largely responsible for Cambridgeshire briefly enjoying First Class status at that time. By contrast there was the “forward player” such as Carpenter’s county colleague, Tom Hayward Snr, as well as the big hitters like George Griffiths of Surrey or the stonewallers like Harry Jupp and William Mortlock, both also of Surrey. Grace was the first to combine all four techniques and was equally at home using any of them.

If his impact on bowling techniques was not so fundamental Grace was also a fine bowler and, until he reached his forties, always took a substantial number of wickets each season, on occasion more than any other bowler. His bowling came in two contrasting styles. As a young man he bowled round arm at a brisk fast medium pace until, around 1880, his arm rose somewhat, and he became a most cunning spin bowler. It is quite clear from contemporary accounts that he was no great spinner of the ball and on his own admission took many wickets with deliveries that appeared about to turn but which did not do so.

The era in which Grace played was not one where fielding skills were highly prized. He was, as befits the fine athlete he was in his youth, a superb outfielder with a fine arm and in the latter part of his career, when his physique was built more for comfort than for speed, he was a good close catcher as well. Overall Grace was undoubtedly as great a competitor as English cricket has ever seen and his desire to win never wavered.

A fine illustration of Grace’s dominance over his peers, and of what a splendid athlete he was, comes from 1876 when he was 28 and in his prime. He had an extraordinary nine days in August. It began with an appearance for MCC against Kent at Canterbury. The home side batted first and totalled 473. Grace bowled 77 four ball overs, more than twice as many as anyone else, and his 4-116 was a creditable return. There was no hint of what was to come in the MCC second innings as the Kent attack bundled them out for 144 in their reply. With plenty of time left as MCC followed on 329 behind, the task of survival seemed hopeless, but Grace recorded the game’s first triple century, 344, as his side batted out the second half of the game. The next highest contribution was 84.

Two days later and it was back home to Gloucestershire and Clifton College where Grace skippered his county against Nottinghamshire, whose attack boasted Alfred Shaw and Fred Morley, two of the best bowlers of the day. Gloucestershire totalled 400, with Grace scoring 177. He took it easy in the Notts first innings, bowling a mere 34 overs whilst allowing brother Fred to bowl as many as 50. But as the visitors followed on it was WG, with 8-69 from another 34 over stint, who hastened the end. As Gloucestershire set off in search of the 31 they needed for a ten wicket victory WG even decided to take a rest, sending out his two brothers to knock off the runs.

Next day it was to nearby Cheltenham where Gloucestershire entertained Yorkshire, then as almost always a power in the land. The White Rose had an attack that comprised four England bowlers; Tom Armitage, Allen Hill, George Ulyett and Tom Emmett. They were no match for WG however, who repeated his Canterbury feat and carried his bat for 318. It was a great shame that rain then interfered, but there were still 36 overs to be bowled by WG as Yorkshire limped to 127-7 in reply to 528. In three matches Grace had scored a total of 839 runs, not to mention bowling those 181 overs, in the course of which he took 15 wickets at a cost of 302 runs.

By the time Grace’s Test career started he had already scored more than 20,000 First Class runs and taken nearly 1,500 wickets and singlehandedly re-written most records. In addition to the achievements already noted he was the first man to do the double of 1,000 runs and 100 wickets in an English season, and the first to do the rather rarer double of 2,000 runs and 100 wickets, something he achieved twice. The only other man to get to that landmark in the 19th century, and even then in 1899 more than twenty years after Grace, was Charlie Townsend, a solicitor who in years to come acted on behalf of Grace’s executors in relation to the administration of his estate.

It almost goes without saying that Grace was the first batsman to score 2000 runs in a season and he was the first to achieve that quintessentially English record of scoring 1,000 runs in May. That feat has only been emulated twice, and the related feat of 1000 runs before the end of May six times, and it must be borne in mind that when Grace achieved it he did so at the age of 46. Finally on major records Grace was, inevitably, the first man to score one hundred centuries, and to illustrate the speed at which he could score he was also the first man known to have scored a First Class century before lunch.

Grace played his first Test match in 1880 at the Oval in what was the first Test ever played on English soil. There is a curious background to the match in that the Australian tourists that summer were a decidedly unpopular group who, when they arrived in England had no fixtures of note arranged at all. There had been trouble in Australia in 1878/79 when Lord Harris took a team down under and he made sure that the 1880 tourists were shunned by the cricketing establishment and they were obliged to travel round the country playing largely scratch teams, against odds, in order to have a fixture list at all. Grace, who had not been with Harris in Australia, did not agree with the stance that was being taken and largely through his lobbying some First Class fixtures were eventually arranged, including that single Test.

England were captained once more by Harris who, having made his peace with the Australian captain Billy Murdoch, won the toss and elected to bat. Grace opened with brother EM and was dismissed four hours later for 152, the first Test century ever recorded by an Englishman. He was dropped in the outfield once on 134, but that apart the innings was unblemished. Australia were obliged to follow on 271 behind after England scored 420 but, their captain leading the way, they recovered to ensure England had to score 57 for victory. Harris changed his batting order for such a modest task, but when the fifth wicket fell he had to send Grace in, and there were no further alarms.

There was just one more Test century for Grace, six years later, again at the Oval, when his 170 paved the way for an England victory by an innings and 217 runs. He struggled early on and was dropped five times, but such was his dominance that when he was second out at 216 he had scored a remarkable 78% of the innings total at that point.

It is worth noting also that in Grace’s time Test cricket was not, as today, revered as the highest form of the game and it is a better measure of his quality how he affected the great match of his day, the Gentleman and Players fixture. In the first 59 years of that particular encounter the Gentleman only won seven times in matches that were played on level terms. In the following 20 years, in matches in which Grace played, the Gentleman won 30 matches and lost only 7.

It must also be remembered that through most of Grace’s career wickets were poor. It was only as the so called <i>Golden Age</i> arrived in 1890 that the standard of pitches improved markedly. Grace was already 42 by then.

As the years passed Grace’s batting seemed to carry on much as before and in both 1895 and 1896 he scored more than 2,000 runs. After the dawn of the <i>Golden Age</i> he bowled less, but still averaged more than 40 wickets a season during the 1890s, and the price he paid for them was around 25. The watershed came in 1899. Prior to the first Test of that summer’s series Grace, despite his fading mobility, had always played for England in England. In that final match though he was barracked for his poor performance in the field, and he accepted that at nearly 51 the time had come for him to pass on the captaincy of England.

The final year of the 19th century was a sad one for Grace in another way as well, as he also fell out for the final time with his county, Gloucestershire, and went on to found his own London County Club. From 1900 until 1904 London County played First Class matches and were based at the old Crystal Palace ground. Even after 1904 Grace continued to raise other invitational sides, and did not play his final First Class match until as late as 1908, by which time he was almost 60. While his fielding may have deteriorated so much that he became a passenger Grace never embarrassed himself with the bat, and while his Gentleman of England side lost by an innings to Surrey in 1908, Grace himself bowed out with innings of 15 and 25.

Cricket historians argue to this day about the status of some of the matches in which Grace played however for these purposes it should simply be noted that in his long First Class career he scored more than 54,000 runs at an average of 39 with at least 124 centuries (some authorities refer to a more traditional figure of 126). In all cricket he scored more than 100,000 runs. In addition he took more than 2,800 First Class wickets at a little over 18 apiece, with 240 five wicket hauls and 64 occasions when he took more than ten wickets in a match. In the field Grace held 875 catches altogether and being, of course, a competent wicket-keeper when he so chose, also made five stumpings.

William Gilbert Grace must have been an interesting character and was certainly one of contrasts. He was clearly a determined and ambitious cricketer who, despite his amateur status, made huge sums of money out of the game. Comparisons over centuries are tricky, but the fee he was able to negotiate for each of his two trips to Australia was the equivalent of around £150,000 today, and he was paid expenses as well. He had, apparently, a rather high-pitched voice and a child-like sense of humour and he certainly made enemies inside, and doubtless outside the game as well, but there are few that seem to have emerged from dealings with him without respect for him.

WG died on 23 October 1915. At 67 he was no great age, but he had suffered a stroke a fortnight beforehand. He had been expected to fully recover, but he became depressed as night time air raids meant that German bombs fell within a few miles of his home in Kent. The man for whom a speeding lump of cork and leather had held no fear was greatly troubled by this enemy that he could not see coming, and the catalyst for his death was a fall as he got out of bed during one air raid, the damage from which led to the heart attack which was the immediate cause of death.

The passing of the man who had, during Victoria’s reign, been said to be, next to William Gladstone, the most instantly recognisable man in the country, gave the newspapers something other than the Great War to report on. That news was no happier of course, but at least it was an opportunity for remembering of happier times and the paying of fulsome tributes to the man who was undoubtedly the greatest cricketer the game had seen.

As the centenary of his death approaches it is fair to say that in the 21st century Grace has most definitely overtaken Gladstone in the recognisability stakes, but he has slipped in the public eye as far as his quality as a cricketer is concerned. But he should not have. His time was too long ago to readily compare him with anyone who followed him, and the few celluloid fragments of his batting in the nets are of an old man. What should be remembered above all else is his dominance over his peers, and the most remarkable statistic of all. Grace had been playing the game for ten years when, at 27, he scored his fiftieth First Class century. In the time it took him to do that every other batsman in the world could manage no more than 109 between them, and no individual more than Harry Jupp’s ten. It goes without saying that no one has come remotely close to managing anything even vaguely comparable since.

And he could bowl as well ……………………….

Leave a comment