From Understanding Springs Forgiveness

Gulu Ezekiel |

For 35 years – from 1976 to 2011 – I held a grudge deep in my heart against the fast bowling tactics of the legendary West Indies cricket team that made them undisputed masters for nearly two decades.

The mighty Windies under the captaincy of first Clive Lloyd and then Viv Richards were like the Brazilian football team – every neutral fan’s favourite. But not mine.

My longstanding grouse arose from the 1976 Test match in Kingston, Jamaica (the chapter in Sunil Gavaskar?s Sunny Days is titled “Barbarism in Kingston”). The highlights were shown in India. What I saw in black and white appalled me.

Years later my interactions with many of the protagonists in both a professional capacity as a sports journalist and my warm friendship with the captain Bishan Singh Bedi in particular only deepened my resentment.

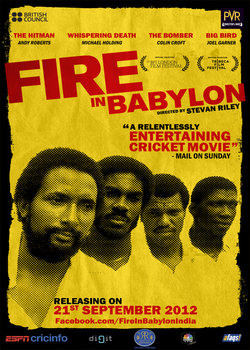

Then last year I heard of the documentary, Fire in Babylon (released in theatres in India on September 21) about the glory days of Windies cricket, now a distant memory since they surrendered their world crown to Australia in 1995. Watching the DVD at home had a profound effect on me.

It allowed me to understand the context of the tactics employed by Lloyd and his pace spearhead Michael Holding which left the Indian batsmen battered and bruised in the pre-helmet days when there were no restrictions on bouncers and home umpires were scared to warn their bowlers.

Forgiveness may be a strong word. After all, no one was killed (though the courageous Anshuman Gaekwad’s injuries were life-threatening). But considering our feeble opening bowling “attacks” of those days, the Windies tactics to my mind were mean and excessive.

The 1975-76 season was the trigger. Lloyd’s men had just returned from a battering in Australia. It was bad enough they were routed 5-1 in what was billed as the world championship of cricket as the dreaded fast bowling pair of Dennis Lillee and Jeff Thomson left them with broken bones and shattered psyches.

What was worse was the racial abuse they had to suffer from the Australian public. It was deeply degrading and left them seething with anger and feelings of revenge.

Lloyd’s job was on the line and when India scored a world record 406 for four to win the third Test at Port of Spain, Trinidad to level the series 1-1, it led to a radical rethink. No longer would spinners play a part, it was going to be all out pace directed at the unprotected heads of the batsmen just as the Aussies had done so mercilessly.

With half his team in hospital, Bedi had no choice but to practically concede the Kingston Test in what Holding and wicket-keeper Deryk Murray refer to as “surrender”. Lloyd won the series 2-1, kept his job and never looked back.

The bowling appeared brutal at the time and hurt me deeply. With West Indies cricket lurching from one crisis to another from the mid-90s till now, it gave me a sense of perverse pleasure every time I saw one of their batsmen hit by an opposition fast bowler. If it was an Indian bowler, for me it was like karma for Kingston ’76.

But context is everything and Fire in Babylon opened my eyes.

For those proud black West Indians cricket was a vehicle to showcase their skills to the world and prove that they were in no way inferior to their white former colonial masters. India in 1976 were simply at the wrong place at the wrong time in cricket history. But it was never personal.

It is another matter now that cricket in the West Indies is heavily dependent on the “East Indian” community. Back then it was all about “Black Power” and so the likes of Rohan Kanhai and Alvin Kallicharan do not get a mention.

I still maintain I am no fan of the West Indian style of all-out pace and punishing batting that was their hallmark.

Cricket was reduced to a battle of resilience and attrition with the awesome fast bowling quartet barely managing 70 overs in a day. The bouncers were overdone and batsmen were forced into a shell of self-preservation.

The authorities’ hands were forced as injuries piled up despite helmets coming in from 1978. Bouncers were curtailed, a minimum of 90 overs per day was mandated. Spin bowling made a glorious comeback. Cricket was no longer one-dimensional and purely physical.

But the Windies were blameless. They had at their disposal an almost endless supply of brilliant fast bowlers and like countries had done throughout cricket history, used them to optimum effect. The condemnation which came mainly from the English media was hypocritical. After all, who had devised Bodyline?

Andy Roberts, Holding, Colin Croft, Joel Garner, the immortal Malcolm Marshall?the list was seemingly endless.

The batting lineup was equally awe-inspiring. No scope for wristy subtlety here either. Led by the regal Viv Richards, backed up by Gordon Greenidge, Desmond Haynes, Lloyd and others, all these past masters have their say, eloquently conveying the pride they took in inspiring their oppressed people.

The greatest tribute one can pay to director Stevan Riley is that his movie is a spiritual successor to Trinidadian CLR James? seminal book Beyond a Boundary that was first released in 1963 and which opened the eyes of the world to the part cricket played in the struggle of the West Indian people. It combined cricket, race and Marxism to convey their poignant story.

Riley uses the magical medium of music to convey his own message, specifically reggae and calypso and the powerful songs of Bob Marley for which the Caribbean is so famous.

It has become cricket’s most hackneyed quote. But I cannot resist ending this “confessional” with James’ immortal line: “What do they know of cricket who only cricket know?”

That could well be the catch-phrase for Fire in Babylon, an inspiring work that forced my change of heart after all these years of resentment and bitterness.

This article originally appeared in Hindustan Times dated Sept. 23, 2012.

Leave a comment