Cricket and Politics

Gulu Ezekiel |

Cricket has historically played a disproportionately large role in the realm of international relations considering it is competed at the highest level by fewer than a dozen nations.

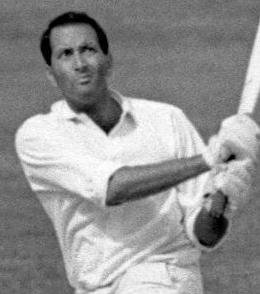

Following the recent death of the iconic English cricketer Basil D’Oliveira at the age of 80 his obituaries centred round the unwitting role he played in the banning of South Africa – the country of his birth – from the international sporting arena due to their abhorrent policy of racial segregation or apartheid.

Discriminated against at home, D?Oliveira made an epic journey to England in 1960 and his Test debut for his adopted land six years later was followed by belated selection for the tour of South Africa in 1968. It is the stuff of cricket legend.

But the cricket world was riled by his original omission from the touring party despite a match-winning 158 against Australia in the preceding Test match. Speculation has always been rife that it was orders from the top from both Pretoria and London that led to that shocking decision. But when one of the players originally chosen had to withdraw due to injury, the path was clear for D?Oliveira.

His eventual selection was condemned as a game of “political football” by the apartheid regime which scored an own-goal when they refused permission to allow “Dolly” to play in South Africa simply because he was not white skinned. The tour was cancelled and two years later South Africa were banned from international cricket. They had earlier been banned from the Olympics as well.

South Africa’s readmission in 1991 came only after the release of Nelson Mandela from prison and the eventual dismantling of apartheid – this final act having been set in motion in 1968 by the selection for the England cricket team of a non-white player for a tour of the land of his birth.

“We shall win the Ashes – but we may very well lose a Dominion” were the prophetic words of Douglas Jardine’s school coach when he heard that his former student was to lead England to Australia in 1932-33 – the infamous “Bodyline” series.

This violent form of bowling devised by Jardine was English cricket’s desperate ploy to staunch the torrent of runs flowing from the bat of Australia’s champion Don Bradman.

The plan worked – England won the series 4-1 and regained the Ashes. But it led to a furore that threatened diplomatic ties between Australia and the “mother country” following a flurry of furious cables between the Australian Cricket Board and the MCC.

No wonder Britain’s secretary of state for the Dominions JH Thomas exclaimed in 1933: “No politics ever introduced in the British Empire ever caused me so much trouble as this damn Bodyline bowling.”

Few sporting rivalries though can match an India/Pakistan cricket match for tension laden with political overtones. It has always been thus though the Board of Control for Cricket in India’s support for Pakistan to gain Test match status (granted just five years after the nation’s birth) has rarely been acknowledged.

Despite the fraught political ties, the Indian and Pakistani cricket boards have twice jointly hosted the World Cup successfully, first in 1987 and then in 1996, the latter with Sri Lanka.

An India/Pakistan World Cup semi-final this year was too much for our political leadership to resist and the showdown at Mohali was turned into a mini-summit when Prime Minister Manmohan Singh invited his Pakistani counterpart Yousaf Raza Gilani to witness the match.

Back in February 1987 Pakistan President General Zia-ul-Haq practically invited himself for the Test match at Jaipur, thus scoring political points over our Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi.

Whether played at home, at the traditional cricket venues around the world or at unusual locations like Singapore, Sharjah and Toronto, a cricket match between India and Pakistan has always been about more than just sport. And that is unlikely to change in the foreseeable future.

Leave a comment