Botham On Film: 1981 And All That

Gareth Bland |

It was while recently sofa-bound and laid low with a dose of the lurgy, exacerbated by a transatlantic flight, that I rediscovered a masterpiece of the cricket documentary genre. “Botham’s Ashes” was first released in late 1981, in the embryonic days of Betamax and VHS tapes and the occasional treat of a rented video. Rented, that is, since they were then so prohibitively expensive that rental was the only option available to most. The label “documentary”

is probably a tad imprecise, though, since “Botham’s Ashes” is more of a highlights package hosted by Richie Benaud, who solicits the thoughts of a 25 year old who had just seen his life transformed in the course of the preceding few months.

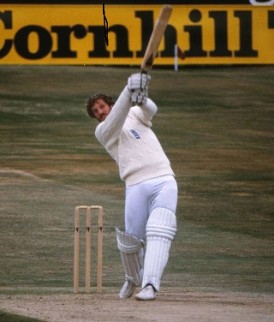

The filming was completed in Botham’s North Yorkshire home, a short time before the hero of the hour was set to take off for England’s tour of India. In the winter recess, the all-rounder looked every inch the national hero. Powerful but still lean, Botham puffed on a cheroot as Benaud probed him about his resignation and the first two, long forgotten Tests of the summer at Trent Bridge and Lord’s. Sporting a trim beard flecked with strawberry red and short hair wet-combed down, this is the pre-mullett, pre-pot bellied figure that would reappear in the English summer of 1982 and after. Exuding a confident air and with regulation white socks tucked inside a natty pair of burgundy New Romantic-era lace-ups, IT Botham could have been any successful professional in his mid-twenties.

The journey begins with footage of those team-mates of Botham’s credited with having made a contribution that summer. Fleeting images of Willis, Dilley and Boycott are all shot during the sunny last couple of days at Lord’s during the Second Test. It is when Benaud turns to the camera after reeling off one celebratory newspaper headline after another that we are reminded of the true nature of the transformation that began at Headingley:

“Ian Botham was a hero. Well, short memories, eh? Well, perhaps they are. Because if you think about it, Headingley came only eleven days after (the second Test) at Lord’s, and I’m not sure a hero would’ve been accorded a reception of this kind as he made his way to the pavillion”

The camera cuts to a lonely figure, head bowed in late afternoon sunshine, as he heads for the gate at the Members’ End. The Duncan Fearnley blade is wrapped under the arm, the gaze floorbound and the stride purposeful. As he enters the gate to mount the steps and head toward the Long Room and the sanctuary of the dressing room, not a soul acknowledges his presence. A polite smattering of applause can be heard from the right of the Members’ End, but it was the averted gazes, fingers fumbling around broadsheets and eerie quiet that ensured that Botham would never acknowledge the members again during his career.

It is easy to forget, with the distance of thirty odd years, just how redolent the English game was of the old establishment back then. With Peter West in his shiny headed, plummy dictioned finery, Lord’s on that final day of the second Test seems like the bastion of old England that it then was. Overall, though, an odd impression comes across: this is most definitely not the seventies, nor does it resemble the brash, garish middle-eighties still to come. Botham, bearded – along with several team-mates – and short-haired, seems frozen in time. Boycott’s protective arm guard still seems oddly modern, even by today’s standards. A teenager today looking at the images from summer’81 might find it hard to place them in time.

Benaud introduces clips of Botham talking after the narrow defeat in the opening Test at Trent Bridge, followed by an interview given after his resignation at Lord’s. The first sees the captain optimistic and sunny, while the mood at Lord’s, minutes after he had tendered his resignation is an altogether different affair. Here Botham is sombre, eyes staring into the middle distance. Moments later, Alec Bedser, chairman of selectors, is interviewed separately by Peter West, the sunlight dimming on the Lord’s balcony. Bedser, he of the East End vowels and ramrod straight back, is another figure it would be difficult to imagine being so prominent in public life today.

A reminder that the chairmanship of selectors would perennially swing from the patrician to the proletarian, Bedser reveals that he had, in fact, made his mind up to sack Botham anyway. The great Surrey quick man intones “we were a bit worried as to Ian’s form”. Following the understatement of the century, Bedser says that Botham should be allowed time to “get back in the groove again”. The young captain had suffered, acknowledges the chairman, not least long-suffering wife Kath. The skipper’s family had been “harassed” adds Bedser, with the emphasis on the first syllable, true to traditional British English pronunciation, an intonation seldom heard today.

In the original Botham’s Ashes, released as autumn turned into winter in 1981, the exploits at Headingley form the bulk of the video, with the Edgbaston and Old Trafford Tests included for Botham’s match-winning 5-1 spell at Birmingham and the breathtaking 118 in murky Manchester. At Edgbaston, a sun-kissed Sunday afternoon still easily recalled from childhood, the smooth tones of Peter Walker welcome us back to Sunday Grandstand and – what’s that – Kim Hughes has just hooked Bob Willis “straight down that man’s throat”. That man, of course, was John Emburey, perhaps unfairly robbed of the man of the match award because of the exploits of the man Bob Willis refers to as “Golden Bollocks”.

Botham’s match winning spell, abetted by some “fairly inept battin'” according to Jim Laker at the end, was concluded with the skittling of Alderman and perhaps the loudest, shrillest roar ever heard on an English cricket ground. Even now, at a distance of more than 33 years, it is almost impossible to watch the denouement of that game without the hairs on the back of the neck rising. Amusingly, the Beeb’s post-match interview with Mike Brearley is held in the tiniest of ante-rooms, more cupboard than high-tech media centre.

At Old Trafford for the fifth Test the murk of Headingley returned. However, whereas Leeds has induced Botham to reach for the long sleeve sweater in order for him to post his 149, at Manchester the dank, clammy mid-August weather meant that the short-sleeves would do. John Woodcock’s rhetorical “Was Botham’s innings the greatest ever?” headline in the following day’s Sunday Times may seem wildly excessive these days, but it is the measure of the effect that the series had on the most senior of writers that even a sage such as Woodcock could be moved to such extravagant praise.

Old Trafford looks like a relic, though. As Botham monsters Lillee, Alderman, Whitney and Bright, the ghosts of the nation’s industrial past are all too apparent, courtesy of the now defunct Lerdy Star Company close to the Warwick Road railway station. National identity, or at least the outward manifestation of it, seems to have changed, too. As Botham blindly carves Lillee time and again into the spectators for six after six, it is into a sea of Union Jacks that the ball rockets. Although, in fairness, the St George Cross is in good supply, fluttering manically as Botham thick edges Lillee within reach of John Dyson at deep third man. Perhaps the one stunning image from the afternoon is the pull for six off Alderman which Botham executes deep into his innings. Rarely has a cricket bat sounded so sweet, “just about the best shot Botham’s played today” intones Benaud, the Sage of Penrith.

Repackaged and rebranded in 2005 as “Botham’s Ashes: The Miracle of Headingley ’81”, the DVD included highlights from each of the five days of the totemic 3rd Test at Headingley; Edgbaston and Old Trafford being consigned to the history bin in this case. James Erskine’s “From The Ashes” from 2011,released in time for the 30th anniversary celebrations, was an overblown, over-rated affair. Ostensibly adding nothing to our understanding of the series and its context, it resorts to repackaging the era through cliche. Even the players seem as though they are either tired of talking about it, or seem unable of breathing life into a still remarkable tale. Worse still, Rodney Hogg resorts to hoary old colonial stereotypes – “We are the English, the BAD English” – as Botany Bay is revisited once more. Even cricket’s greatest contemporary chronicler, Gideon Haigh, is made to appear like just another talking head on a “Best of” documentary.

The same cannot be said for Channel Four’s twentieth anniversary documentary, entitled – wait for it – “Botham’s Ashes”. Talking heads and journos are eschewed, as it is left to those at the heart of the drama to do the talking. And what a fine job they do of it, too. Most revealing are the Australians: Lillee, Border, Hughes and Marsh in particular, who reveal just what a disunited bunch they were throughout that summer. The crux of Christian Ryan’s Kim Hughes biography rested on the resentment of Hughes’ senior pros to his authority. Lillee in particular squirms in his seat as the question is raised, while Hughes himself is revealed as a genuinely tragic sporting figure; the first sight, almost twenty years after the event, of the husk of a batting prince, his story still yet to be chronicled by Ryan at that point.

It is, though, the 3rd Test at Headingley that is most immediately recalled. There is a sequence in the 2005 DVD version, right at the end of the third day’s play, which is included in its entirety. Perhaps inadvertently, the first three deliveries of Lillee’s first over with the new ball, and first of the innings, are replayed in real-time. It seems a million miles away from the studied, slick professionalism of today. Lillee starts of with three short-sleeved sweaters, then strips down to two, then finally one. Boycott, gloves off at the non-striker’s end, follows Lillee into the crease, watching his old nemesis intently. Between deliveries, Boycs glances skywards towards the thickly growing blanket of grey gloom overhead. With the final delivery Lillee pitches one up to Gooch who edges to Alderman at slip. The slips, gulley and point look so close up and compact that it could almost be catching practice. Lillee, the legendary warrior still recovering from pneumonia, was then incredibly just days past his 32nd birthday, despite performing a passable impression of a 50 year old.

With the players just back on the field after tea, Lillee seems to be wrestling with the aftermath of perhaps one sandwich too many. Back in the commentary box, a chorus of clanking spoons, plates and cups is easily discernible behind the genteel commentary. It is all so quaint and oddly soothing and accessible. Sky Sports One this most definitely is not.

During Botham’s fourth day century a collection of images jar with their quaintness and quintessential Englishness. Quintessential, that is, with a heavy Northern tint. Whirling chimney pots from behind the Kirkstall Lane End, blue anoraks on youths in the first week of summer holiday. My personal favourite, however, is the shot of the vicar, salt and pepper hair blowing in the breeze, just to the left of the swirling conifers adjacent to the Kirkstall Lane End sightscreen. Clapping heartily as Botham lambasts Lawson over mid-off for four, the vicar in the crowd seems so incongruous, somehow, during the week in which Botham resurrected the game and Terry Hall and The Specials were number 1 with “Ghost Town”. All this, and more, amid a time when riots swept Liverpool, London and Bristol and the unemployment figure topped three million. A week later and the woman formerly known as Diana Spencer would enter into a union with one Charles Phillip Arthur George Windsor.

Watching the documentaries all over again is a reminder of the essential oddities of that glorious summer. There was the weather for a start. This is meant to be our summer game, right? Edgbaston stands out for its glorious technicolour glow and the boom of the Birmingham crowd on that final Sunday. Headingley and Old Trafford, though, are all mist, murk and gloom. It is as though Ken Loach or John Osborne had specially crafted the conditions for a northern cricketing kitchen sink drama.

There is a striking image which conveys this quite acutely in Rob Steen and Alastair McLellan’s 500-1: The Miracle of Headingley ’81. Initially launched on the twentieth anniversary in 2001, the photo of Ray Bright as Willis applies the coupe de grace on the Tuesday afternoon is a gem. Seen from the vicinity of point, the camera pans out across the ground and captures the stand at deep mid-wicket. A cluster of anorak clad spectators punctuate a spartan, dilapidated stand. Instead of looking like a Test match is taking place in July’s third week, Headingley looks like a run-down provincial Rugby League ground in February. This does not, however, detract from the charm one jot. If anything, the allure of Headingley ’81 is even enhanced.

Botham is as much a part of the social history of 1981 as Margaret Thatcher, Toxteth, Brixton and The Yorkshire Ripper. It would be glib and crass to say that he enacted some form of deliverance for the crimes of The Ripper with his deeds in this Leeds suburb, but he helped put a smile on the face of the nation and, more importantly, he made people dream, especially a generation of incipient young cricket followers. He did not get anyone off the dole, or personally stop any riots, but the 1981 Ian Botham made a Test series in his own image, completed a personal turnaround seasoned scribes likened to that of Lazarus, and induced a venerable Australian commentator to introduce the term “confectionery stall” into the national lexicon.

It is this timeless vintage we should remember best and most fondly, not the tubby Paul Calf prototype that emerged in later years. He can seem a bit of a reactionary old duffer at times these days, indeed Andrew Pulver of The Guardian dubbed him “undeniably Clarksonesque” in 2011. Maybe it is time to stop going on about 1981 and merely consign it to history. After all, it is as long ago now as the magical summer of 1947 was back in 1981. And, back then, in my youthful ignorance of all things so prehistoric, I could not, for the life of me, work out why people were so fixated with that particular Post-War summer.

Even Mike Atherton appeared to have had enough of it in 2001, twenty years after the event, as England took on Australia once more. In the final analysis, though, it is still special. The 2005 Ashes summer may have been fought between incontestably superior sides, but almost a decade on it pales against the human element of that series set at the dawn of the eighties. Why, then, does the story of 1981 still endure when we are now saturated by so many formats of the game all these years later? Michael Henderson came as close as any to nailing the significance of the series when he said “No England cricketer has known the glory that Botham knew in 1981. No England cricketer ever will. That is why Headingley matters”. In the absence of any other explanation that will most surely do.

Leave a comment